The Great Indian Novel 60

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version)

Thursday, May 8, 1997 Eleventh Series, Vol. XIV No. 6 Vaisakha 18, 1919 (Saka) LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version) Fourth Session (Part-IV) (Eleventh Lok Sabha) ir.ufr4*B* (Vol. XIV contains No. 1 to 12) l o k sa b h a secretariat NEW DELHI I’ rn c Rs >0 00 EDITORIAL BOARD Shri S. Gopalan Secretary General Lok Sabha Shri Surendra Mishra Additional Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Shri P.C. Bhatt Chief Editor Lok Sabha Secretariat Shri Y.K.. Abrol Senior Editor Shri S.C. Kala Assistant Editor [Original English Proceedings included in English Version and Original Hindi Proceedings included in Hindi Version will be treated as authoritative and not the translation thereof.] „ b . »• KB (ftb’ • • • M o d FOC Col./line or. vallabh BhaiKathiria vailabha Bhai Kathiria (i)/M Shri N .S .VChitthan . Sr i N.S-V. 'n.tNit ( i i ) /'/ Dr. Ran Krishna Kusnaria nc. Ran Krv.<» .fhnaria 5/14 Shri Ran V ilas Pa swan Shri R® Villa* Pa^ai 8/14 (fioni below) Shri Datta Meghe Shri Datta Maghe 10/10 (Irotr below) Shrimati Krishna Bose Shrimati K irsh n a Bose 103/It> Shri Sunder La i Patva Shri Sunder Patva 235/19 Sh ri Atal Bihari Vajpayee Shri Atal Bihari Vajpa« 248/28 Shri Mchaiwaa Ali ^ T o t Shri Hdhsmnad Ali hohraaf Fatmi 2 5 3 /1 .1 4 F atm i 2 5 4 /8 Shri aikde® P m* w 1 Shri Sukhaev Pasnai 378/24 3BO/3 CONTENTS [Eleventh Series, Vol. XIV, Fourth Session (Part-IV) 1997/1919 (Saka] No. -

A Comprehensive Guide by Jack Watts and Conner Reynolds Texts

A Comprehensive Guide By Jack Watts and Conner Reynolds Texts: Mahabharata ● Written by Vyasa ● Its plot centers on the power struggle between the Kaurava and Pandava princes. They fight the Kurukshetra War for the throne of Hastinapura, the kingdom ruled by the Kuru clan. ● As per legend, Vyasa dictates it to Ganesha, who writes it down ● Divided into 18 parvas and 100 subparvas ● The Mahabharata is told in the form of a frame tale. Janamejaya, an ancestor of the Pandavas, is told the tale of his ancestors while he is performing a snake sacrifice ● The Genealogy of the Kuru clan ○ King Shantanu is an ancestor of Kuru and is the first king mentioned ○ He marries the goddess Ganga and has the son Bhishma ○ He then wishes to marry Satyavati, the daughter of a fisherman ○ However, Satyavati’s father will only let her marry Shantanu on one condition: Shantanu must promise that any sons of Satyavati will rule Hastinapura ○ To help his father be able to marry Satyavati, Bhishma renounces his claim to the throne and takes a vow of celibacy ○ Satyavati had married Parashara and had a son with him, Vyasa ○ Now she marries Shantanu and has another two sons, Chitrangada and Vichitravirya ○ Shantanu dies, and Chitrangada becomes king ○ Chitrangada lives a short and uneventful life, and then dies, making Vichitravirya king ○ The King of Kasi puts his three daughters up for marriage (A swayamvara), but he does not invite Vichitravirya as a possible suitor ○ Bhishma, to arrange a marriage for Vichitravirya, abducts the three daughters of Kasi: Amba, -

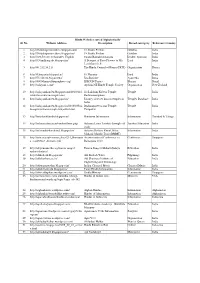

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Transition Into Kaliyuga: Tossups on Kurukshetra

Transition Into Kaliyuga: Tossups On Kurukshetra 1. On the fifteenth day of the Kurukshetra War, Krishna came up with a plan to kill this character. The previous night, this character retracted his Brahmastra [Bruh-mah-struh] when he was reprimanded for using a divine weapon on ordinary soldiers. After Bharadwaja ejaculated into a vessel when he saw a bathing Apsara, this character was born from the preserved semen. Because he promised that Arjuna would be the greatest archer in the world, this character demanded that (*) Ekalavya give him his right thumb. This character lays down his arms when Yudhishtira [Yoo-dhish-ti-ruh] lied to him that his son is dead, when in fact it was an elephant named Ashwatthama that was dead.. For 10 points, name this character who taught the Pandavas and Kauravas military arts. ANSWER: Dronacharya 2. On the second day of the Kurukshetra war, this character rescues Dhristadyumna [Dhrish-ta-dyoom-nuh] from Drona. After that, the forces of Kalinga attack this character, and they are almost all killed by this character, before Bhishma [Bhee-shmuh] rallies them. This character assumes the identity Vallabha when working as a cook in the Matsya kingdom during his 13th year of exile. During that year, this character ground the general (*) Kichaka’s body into a ball of flesh as revenge for him assaulting Draupadi. When they were kids, Arjuna was inspired to practice archery at night after seeing his brother, this character, eating in the dark. For 10 points, name the second-oldest Pandava. ANSWER: Bhima [Accept Vallabha before mention] 3. -

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

Shashi Deshpande's Treatment of Indian Epic Myths: a Reinterpretation

© 2016 IJRAR Feb 2016, Volume 3, Issue 1 www.ijrar.org (E-ISSN 2348-1269, P- ISSN 2349-5138) Shashi Deshpande’s Treatment of Indian Epic Myths: A Reinterpretation Ravish Kumar Assistant Teacher D. N. (+2) School, Gola Road, Muzaffarpur According to Jasodhara Bagchi, Indian womanhood is constituted by a multilayered accretion of myths, which in their turn essentialize and thereby homogenize the myth of ‘Bharatiyanari’ within the hegemonic ideology of patriarchy and thus serve patriarchy in both its local and global manifestations. As per these myths a women is the pure vessel of virginity, chaste wife, weak and owned by her husband or the self-denying mother, never an independent entity.1 Deshpande reverses this Pativrata myth by presenting her protagonists as vulnerable to a certain extent. Shashi Deshpande has interpreted the stories of mythological women like Sita, Draupadi and Kunti and given them a liberated voice in her collection of short stories The Stone Women. Even in her novels neither Jaya in ‘That Long Silence’, nor Urmi in ‘The Binding Vine’ are presented as Pativratas. Certain other fictions of womanhood prevalent in India are concerned with woman’s sexuality and motherhood. Thus the ideal of womanhood is that of chastity, purity, gentle tenderness and a singular faithfulness, which cannot be destroyed or even disturbed by her husband’s rejections. In India motherhood is usually glorified. But the mental anguish and trauma that a woman undergoes during this phase of her life are often neglected by patriarchy who constructs the images of ideal motherhood. Her protagonist Jaya, through a process of introspection, realizes the patriarchal agenda behind the construction of these myths of femininity and she comes out of the illusion that all these myths are natural and try to assert themselves. -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

List of the Hindu Mandirs in Sikkim: (336)

LIST OF THE HINDU MANDIRS IN SIKKIM: (336) EAST: Sl. No. Name Location District/Sub-Division 1. Aho Ongkeshwar Mandir Aho Gangtok 2. Amba Mandir. Amba Pakyong. 3. Aritar- Rhenock Durga Mandir Aritar Rongli. 4. Aritar Sarva Janik Shiva Mandir Aritar Rongli. 5. Bara Pathing Mandir Bara Pathing Pakyong 6. Bhanugram Krishna Mandir Bhanugram Gangtok 7. Burtuk Shiva Temple Burtuk Gangtok. 8. Beyga Devi Mandir Beyga Pakyong. 9. Biring Durga Mandir. Biring Pakyong. 10. Chenje Singha Devi Mandir Chenje Gangtok 11. Changey Singha Devi Mandir Changey Pakyong. 12. Chujachen Shivalaya Mandir Chujachen Pakyong. 13. Chota Singtam Shiva Mandir Chota Shing Gangtok. 14. Centre Pandam Shiva Mandir. Centre Pandam Gangtok. 15. Chandmari Shiva Mandir. Chandmari Gangtok. 16. Duga Bimsen Mandir. Duga Gangtok. 17. Duga Krishna Mandir. Duga Gangtok 18. Dikiling Pacheykhani Shivalaya Mandir. Dikiling Pakyong. 19. Dikiling Pacheykhani Radha Krishna Mandir. Dikiling Pakyong. 20. Dikchu Shiva Mandir Dikchu Gangtok 21. Dara Gaon Shiva Mandir. Assam Lingzey Gangtok. 22. Dolepchan Durga Mandir Dolepchan Rongli. 23. Gangtok Thakurbari Mandir. Gangtok Bazaar Gangtok. 24. Jalipool Durga Mandir Jalipool Gangtok 25. Khamdong-Aritar Shiva Mandir Aritar Gangtok 26. Khamdong Durga Mandir. Khamdong Gangtok. 27. Khamdong Krishna Mandir. Khamdong Gangtok. 28. Khesay Durga Mandir U. Khesey Gangtok 29. Kambal Shiva Mandir. Kambol Gangtok. 30. Kamary Durga Mandir Kamary Pakyong. 31. Kokoley Guteshwar Shiva Mandir Kokoley Gangtok 32. Luing Thami Durga Mandir. Thami Danra Gangtok. 33. Lingtam Durga Mandir. Lingtam Rongli. 34. Lingtam Devi Mandir. Lingtam Rongli. 35. Luing Mahadev Shiva Mandir. Luing Gangtok. 36. Lower Samdong Hareshwar Shiva Mandir. Lower Samdong Gangtok 37. Lamaten Mata Mandir Lamaten Pakyong. -

Transgressive Desires in Indian Mythology: a Reading of Shikhandi and Other Tales They Don’T Tell You

© 2020 JETIR April 2020, Volume 7, Issue 4 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Transgressive Desires in Indian Mythology: A Reading of Shikhandi and Other Tales They Don’t Tell You Aiswarya Lakshmi M. Ph.D Research Scholar in English, Kannur University Central Library, Kannur, Kerala. Abstract: Stories of a particular time always resonate with its society. In the Indian milieu, stories have been passed down from one generation to the next with certain ideological modifications. These versions change from one another based on the time, space and socio-cultural matrix of the community they are germinated from. Many Postmodernist Indian writers in English dismantle authority and sexist values by breaking stereotypes. This paper attempts to explore how notions of agency and victimhood are brilliantly dealt within these modern retellings of Indian epics. The paper will also focus on establishing the idea that the marginalized like sexual minorities and gender queer persons shared a comparatively better position in the prehistoric times in South Asia. Instead of marginalization queerness was deemed as ‘natural’ or sometimes celebrated. To validate this argument, the paper has analysed Devdutt Pattanaik’s book Shikhandi and The Other Tales They Don't Tell You. It is a collection of short stories from several myths across India which express the suppressed voices in the Grand Narratives of Indian mythology. The author exposes the queer presence in Indian folklores which describe about the gays, lesbians and hijras of the society which accepts queer behaviour, be it cross dressing or homosexual intimacies, as perfectly natural. Intex Terms: Queer Narrative, Folklore, Hegemony, Myth, Ideology, Retelling, Grand Narrative. -

Entertainment Worldwelcome to Entertainment World HERE You

Welcome To Entertainment WorldWelcome To Entertainment World HERE You Can get all the Latest Movies, Songs, Games And Softwares for free.English Movies English Movies In Hindi Hindi Movies Hindi Songs PC Softwares PC Games Punjabi Songs Disclaimer Search Stuffs On This Blog Latest Hindi ( Bollywood ) Songs : Delhi 6 Billu Barber 42 Kms Jugaad Aasma Luck By Chance Dev. D Jumbo Victory Slumdog Millionaire Raaz The Mystery Continues... Chandni Chowk To China Wafaa Ghajini Meerabai Not Out Sorry Bhai Khallballi Dil Kabaddi Ek Vivaah Aisa Bhi Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi Yuvvraaj Kaashh Mere Hote My friends COLLECTOR ZONE Groovy Corner Masti Zone Movies Zone Categories Animated Movies Applications Bollywood Movies Christmas Dvd Ripped Movies DvdRipped Movies Ebooks English Movie's English Movie's In Hindi English Movies Fun Corner Hindi Movies Hindi Song's Hollywood Movies Masti Cafe Special Mobile Stuff NEWS Old Hindi Movies PC Games PC Software's Punjabi Movies Punjabi Song's Soundtracks Telugu Movies Telugu Songs Tools And Tips Trailer Video Song's Chat Here!!!!!!! Advertise on www.masti.tk Powered By AdBrite But Sponsered By Manveer Singh Your Ad Here HAPPY NEW YEAR HAPPY NEW YEAR 2009 HAPPY NEW YEAR 2009 TO ALL MY SITE VISITORS Labels: Greetings, Masti Cafe Special, NEWS HAPPY NEW YEAR HAPPY NEW YEAR 2009 HAPPY NEW YEAR 2009 TO ALL MY SITE VISITORS Labels: Greetings, Masti Cafe Special, NEWS Lucky by chance 2008HQ320Kbps Original CDRip Music Director : Shankar Ehsaan Loy Cast : Farhan Akhtar , Konkona Sen Sharma Label: Big Music 01.Yeh Zindagi -

Kalki's Avatars

KALKI’S AVATARS: WRITING NATION, HISTORY, REGION, AND CULTURE IN THE TAMIL PUBLIC SPHERE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Akhila Ramnarayan. M.A. ****** The Ohio State University 2006 Approved by Dissertation Committee: Professor Chadwick Allen, Adviser Adviser Professor Debra Moddelmog, Adviser Professor James Phelan Adviser English Graduate Program ABSTRACT Challenging the English-only bias in postcolonial theory and literary criticism, this dissertation investigates the role of the twentieth-century Tamil historical romance in the formation of Indian and Tamil identity in the colonial period. I argue that Tamil Indian writer-nationalist Kalki Ra. Krsnamurti’s (1899-1954) 1944 Civakamiyin Capatam (Civakami’s Vow)—chronicling the ill-fated wartime romance of Pallava king Narasimhavarman (630-668 CE) and fictional court dancer Civakami against the backdrop of the seventh-century Pallava-Chalukya wars—exemplifies a distinct genre of interventionist literature in the Indian subcontinent. In Kalki’s hands, the vernacular novel became a means by which to infiltrate the colonial imaginary and, at the same time, to envision a Tamil India untainted by colonial presence. Charting the generic transformation of the historical romance in the Tamil instance, my study provides 1) a refutation of the inflationary and overweening claims made in postcolonial studies about South Asian nationalism, 2) a questioning of naïve binaries such as local and global, cosmopolitan and vernacular, universal and particular, traditional and modern, in examining the colonial/postcolonial transaction, and 3) a case for a less grandiose and more carefully historicized account of bourgeois nationalism than has previously been provided by postcolonial critics, accounting for its complicities with ii and resistances to discourses of nation, region, caste, and gender in the late colonial context.