Claiming Sounds, Constructing Selves: the Racial and Social

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Published Papers of the Ethnomusicology Symposia

International Library of African Music PAPERS PRESENTED AT THE SYMPOSIA ON ETHNOMUSICOLOGY 1ST SYMPOSIUM 1980, RHODES UNIVERSITY (OUT OF PRINT) CONTENTS: The music of Zulu immigrant workers in Johannesburg Johnny Clegg Group composition and church music workshops Dave Dargie Music teaching at the University of Zululand Khabi Mngoma Zulu children’s songs Bongani Mthethwa White response to African music Andrew Tracey 2ND SYMPOSIUM 1981, RHODES UNIVERSITY (OUT OF PRINT) CONTENTS: The development of African music in Zimbabwe Olof Axelsson Towards an understanding of African dance: the Zulu isishameni style Johnny Clegg A theoretical approach to composition in Xhosa style Dave Dargie Music and body control in the Hausa Bori spirit possession cult Veit Erlmann Musical instruments of SWA/Namibia Cecilia Gildenhuys The categories of Xhosa music Deirdre Hansen Audiometric characteristics of the ethnic ear Sean Kierman The correlation of folk and art music among African composers Khabi Mngoma The musical bow in Southern Africa David Rycroft Songs of the Chimurenga: from protest to praise Jessica Sherman The music of the Rehoboth Basters Frikkie Strydom Some aspects of my research into Zulu children’s songs Pessa Weinberg 3RD SYMPOSIUM 1982, UNIVERSITY OF NATAL and 4TH SYMPOSIUM 1983, RHODES UNIVERSITY CONTENTS: The necessity of theory Kenneth Gourlay Music and liberation Dave Dargie African humanist thought and belief Ezekiel Mphahlele Songs of the Karimojong Kenneth Gourlay An analysis of semi-rural and peri-urban Zulu children’s songs Pessa Weinberg -

Music and Inter-Generational Experiences of Social Change in South Africa

All Mixed Up: Music and Inter-Generational Experiences of Social Change in South Africa Dominique Santos 22113429 PhD Social Anthropology Goldsmiths, University of London All Mixed Up: Music and Inter-Generational Experiences of Social Change in South Africa Dominique Santos 22113429 Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for a PhD in Social Anthropology Goldsmiths, University of London 2013 Cover Image: Party Goer Dancing at House Party Brixton, Johannesburg, 2005 (Author’s own) 1 Acknowledgements I owe a massive debt to a number of people and institutions who have made it possible for me to give the time I have to this work, and who have supported and encouraged me throughout. The research and writing of this project was made financially possible through a generous studentship from the ESRC. I also benefitted from the receipt of a completion grant from the Goldsmiths Anthropology Department. Sophie Day took over my supervision at a difficult point, and has patiently assisted me to see the project through to submission. John Hutnyk’s and Sari Wastel’s early supervision guided the incubation of the project. Frances Pine and David Graeber facilitated an inspiring and supportive writing up group to formulate and test ideas. Keith Hart’s reading of earlier sections always provided critical and pragmatic feedback that drove the work forward. Julian Henriques and Isaak Niehaus’s helpful comments during the first Viva made it possible for this version to take shape. Hugh Macnicol and Ali Clark ensured a smooth administrative journey, if the academic one was a little bumpy. Maia Marie read and commented on drafts in the welcoming space of our writing circle, keeping my creative fires burning during dark times. -

A Crash of Drums Durban By

LAT / LONG: 29.53° S, 31.03° E DURBAN ‘It’s the sound that gets to you A CRASH first,’ says David ‘Qadashi’ Jenkins. ‘A loud crashing of drums before OF DRUMS you even see the dancers. We heard it while we were still on the street, walking towards the hostel. It was 2012 and I’d just moved to Durban from Empangeni. My mentor, Maqhinga Radebe, took me to the Dalton Hostels on Sydney Road to see them dancing. But, of course, you hear it first. That tumultuous crash, a tremendous sound produced on huge marching band drums. You can hear it as far away as Davenport Centre, which is a few blocks up – you’ll hear it on a Sunday if you listen out for it.’ Jenkins grew up in northern KwaZulu-Natal, where he fell in love with Zulu culture. He’s never looked back; his boyhood obsession with maskandi has evolved into a thriving music career. Yet, even after years spent studying Zulu music traditions, he says witnessing Umzansi war dancing left him breathless. ‘The closer we got, the louder those crashing drums grew and eventually we were in the presence of these potent, DURBAN powerful dancers – workers who stay at the hostels and who dance on Sundays. The drumming is the heart of the music, but with harmonies sung over that, incredible war songs running over this loud drum beat. There are up to 20 singers who stand in a semi-circle, and up to ten men dancing at a time. And they move back and forth, swapping out all the time. -

Issue 148.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 148 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 Little Fish Fins are going swimmingly for Oxford’s brightest new rock sprats - interview inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] AS HAS BEEN WIDELY Oxford, with sold-out shows by the REPORTED, RADIOHEAD likes of Witches, Half Rabbits and a released their new album, `In special Selectasound show at the Rainbows’ as a download-only Bullingdon featuring Jaberwok and album last month with fans able to Mr Shaodow. The Castle show, pay what they wanted for the entitled ‘The Small World Party’, abum. With virtually no advance organised by local Oxjam co- press or interviews to promote the ordinator Kevin Jenkins, starts at album, `In Rainbows’ was reported midday with a set from Sol Samba to have sold over 1,500,000 copies as well as buskers and street CSS return to Oxford on Tuesday 11th December with a show at the in its first week. performers. In the afternoon there is Oxford Academy, as part of a short UK tour. The Brazilian elctro-pop Nightshift readers might remember a fashion show and auction featuring stars are joined by the wonderful Metronomy (recent support to Foals) that in March this year local act clothes from Oxfam shops, with the and Joe Lean and the Jing Jang Jong. Tickets are on sale now, priced The Sad Song Co. - the prog-rock main concert at 7pm featuring sets £15, from 0844 477 2000 or online from wegottickets.com solo project of Dive Dive drummer from Cyberscribes, Mr Shaodow, Nigel Powell - offered a similar deal Brickwork Lizards and more. -

Garage House Music Whats up with That

Garage House Music whats up with that Future funk is a sample-based advancement of Nu-disco which formed out of the Vaporwave scene and genre in the early 2010s. It tends to be more energetic than vaporwave, including elements of French Home, Synth Funk, and making use of Vaporwave modifying techniques. A style coming from the mid- 2010s, often explained as a blend of UK garage and deep home with other elements and strategies from EDM, popularized in late 2014 into 2015, typically mixes deep/metallic/sax hooks with heavy drops somewhat like the ones discovered in future garage. One of the very first house categories with origins embeded in New York and New Jersey. It was named after the Paradise Garage bar in New york city that operated from 1977 to 1987 under the prominent resident DJ Larry Levan. Garage house established along with Chicago home and the outcome was home music sharing its resemblances, affecting each other. One contrast from Chicago house was that the vocals in garage house drew stronger impacts from gospel. Noteworthy examples consist of Adeva and Tony Humphries. Kristine W is an example of a musician involved with garage house outside the genre's origin of birth. Also understood as G-house, it includes very little 808 and 909 drum machine-driven tracks and often sexually explicit lyrics. See likewise: ghettotech, juke house, footwork. It integrates components of Chicago's ghetto house with electro, Detroit techno, Miami bass and UK garage. It includes four-on-the-floor rhythms and is normally faster than a lot of other dance music categories, at approximately 145 to 160 BPM. -

Mirror, Mediator, and Prophet: the Music Indaba of Late-Apartheid South Africa

VOL. 42, NO. 1 ETHNOMUSICOLOGY WINTER 1998 Mirror, Mediator, and Prophet: The Music Indaba of Late-Apartheid South Africa INGRID BIANCA BYERLY DUKE UNIVERSITY his article explores a movement of creative initiative, from 1960 to T 1990, that greatly influenced the course of history in South Africa.1 It is a movement which holds a deep affiliation for me, not merely through an extended submersion and profound interest in it, but also because of the co-incidence of its timing with my life in South Africa. On the fateful day of the bloody Sharpeville march on 21 March 1960, I was celebrating my first birthday in a peaceful coastal town in the Cape Province. Three decades later, on the weekend of Nelson Mandela’s release from prison in February 1990, I was preparing to leave for the United States to further my studies in the social theories that lay at the base of the remarkable musical movement that had long engaged me. This musical phenomenon therefore spans exactly the three decades of my early life in South Africa. I feel privi- leged to have experienced its development—not only through growing up in the center of this musical moment, but particularly through a deepen- ing interest, and consequently, an active participation in its peak during the mid-1980s. I call this movement the Music Indaba, for it involved all sec- tors of the complex South African society, and provided a leading site within which the dilemmas of the late-apartheid era could be explored and re- solved, particularly issues concerning identity, communication and social change. -

Curren T Anthropology

Forthcoming Current Anthropology Wenner-Gren Symposium Curren Supplementary Issues (in order of appearance) t Human Biology and the Origins of Homo. Susan Antón and Leslie C. Aiello, Anthropolog Current eds. e Anthropology of Potentiality: Exploring the Productivity of the Undened and Its Interplay with Notions of Humanness in New Medical Anthropology Practices. Karen-Sue Taussig and Klaus Hoeyer, eds. y THE WENNER-GREN SYMPOSIUM SERIES Previously Published Supplementary Issues April THE BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY OF LIVING HUMAN Working Memory: Beyond Language and Symbolism. omas Wynn and 2 POPULATIONS: WORLD HISTORIES, NATIONAL STYLES, 01 Frederick L. Coolidge, eds. 2 AND INTERNATIONAL NETWORKS Engaged Anthropology: Diversity and Dilemmas. Setha M. Low and Sally GUEST EDITORS: SUSAN LINDEE AND RICARDO VENTURA SANTOS Engle Merry, eds. V The Biological Anthropology of Living Human Populations olum Corporate Lives: New Perspectives on the Social Life of the Corporate Form. Contexts and Trajectories of Physical Anthropology in Brazil Damani Partridge, Marina Welker, and Rebecca Hardin, eds. e Birth of Physical Anthropology in Late Imperial Portugal 5 Norwegian Physical Anthropology and a Nordic Master Race T. Douglas Price and Ofer 3 e Origins of Agriculture: New Data, New Ideas. The Ainu and the Search for the Origins of the Japanese Bar-Yosef, eds. Isolates and Crosses in Human Population Genetics Supplement Practicing Anthropology in the French Colonial Empire, 1880–1960 Physical Anthropology in the Colonial Laboratories of the United States Humanizing Evolution Human Population Biology in the Second Half of the Twentieth Century Internationalizing Physical Anthropology 5 Biological Anthropology at the Southern Tip of Africa The Origins of Anthropological Genetics Current Anthropology is sponsored by e Beyond the Cephalic Index Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Anthropology and Personal Genomics Research, a foundation endowed for scientific, Biohistorical Narratives of Racial Difference in the American Negro educational, and charitable purposes. -

Papering the Cracks in South Africa the Role of ‘Traditional’ and ‘New’ Media in Nation-Negotiation Around Julius Malema on the Eve of the 2010 FIFA World Cup™

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town (Un)papering the cracks in South Africa The role of ‘traditional’ and ‘new’ media in nation-negotiation around Julius Malema on the eve of the 2010 FIFA World Cup™ By Erika Rodrigues RDRERI002 A minor dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the award of the degree of Master of Social Sciences in Social Anthropology Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town 2011 Declaration University of Cape Town This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature________________________________________________ Date __________09.09.2011___________ ABSTRACT In April 2010, amidst the nation-unifying discourses prevalent during the preparation for the 2010 FIFA Soccer World Cup™ to be hosted in South Africa, a series of events gave rise to the revitalization of other discourses in the national media: those of racial polarization and the possibility of a race war. The public singing of the “Shoot the Boer” struggle song by ANCYL leader Julius Malema and the subsequent murder of AWB leader Eugene Terre’Blanche, two events which were being attributed a causal link in national media, was one of the main reasons for the revitalization of these discourses. -

The BG News October 14, 2005

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 10-14-2005 The BG News October 14, 2005 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News October 14, 2005" (2005). BG News (Student Newspaper). 7496. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/7496 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. State University FRIDAY October 14, 2005 ECHELON: Check out The Pulse to get religious PM SHOWERS and rock out with the HIGH: 73 mWM members of 30 Seconds www.bgnews.com to Mars; PAGE 8 independent student press VOLUME 100 ISSUE 38 KNOW IX A II itBMim Just call him 'Joe' Joe Schriner hits the Schriner, 50, is a one-man I'm at home ... I cut my own political party, touring the coun- yard, I change the kid's diapers. I campaign trail as the try in preparation for his third play some sandlot with the kids Average Joe' candidate election, despite being left off when I'm back in Cleveland." the ballot each year. Schriner said there is a com- By lason A Duon His distinctive platform is mon bond with the individuals REPORIER dominated by a pro-life posi- he meets'while campaigning. -

Mediated Music Makers. Constructing Author Images in Popular Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII, on the 10th of November, 2007 at 10 o’clock. Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. © Laura Ahonen Layout: Tiina Kaarela, Federation of Finnish Learned Societies ISBN 978-952-99945-0-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-4117-4 (PDF) Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. ISSN 0785-2746. Contents Acknowledgements. 9 INTRODUCTION – UNRAVELLING MUSICAL AUTHORSHIP. 11 Background – On authorship in popular music. 13 Underlying themes and leading ideas – The author and the work. 15 Theoretical framework – Constructing the image. 17 Specifying the image types – Presented, mediated, compiled. 18 Research material – Media texts and online sources . 22 Methodology – Social constructions and discursive readings. 24 Context and focus – Defining the object of study. 26 Research questions, aims and execution – On the work at hand. 28 I STARRING THE AUTHOR – IN THE SPOTLIGHT AND UNDERGROUND . 31 1. The author effect – Tracking down the source. .32 The author as the point of origin. 32 Authoring identities and celebrity signs. 33 Tracing back the Romantic impact . 35 Leading the way – The case of Björk . 37 Media texts and present-day myths. .39 Pieces of stardom. .40 Single authors with distinct features . 42 Between nature and technology . 45 The taskmaster and her crew. -

Roll to Hard Core Punk: an Introduction to Rock Music in Durban 1963 - 1985

Lindy van der Meulen FROM ROCK 'N 'ROLL TO HARD CORE PUNK: AN INTRODUCTION TO ROCK MUSIC IN DURBAN 1963 - 1985 This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the degree of Master of Music at the University of Natal DECEMBER 1 995 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The financial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research project is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. The valuable assistance and expertise of my supervisors, Professors Christopher Ballantine and Beverly Parker are also acknowledged. Thanks to all interviewees for their time and assistance. Special thanks to Rubin Rose and David Marks for making their musical and scrapbook collections available. Thanks also to Ernesto Marques for making many of the South African punk recordings available to me. DECLARATION This study represents original work of the author and has not been submitted in any other form to another University. Where use has been made of the work of others, this has been duly acknowledged in the text . .......~~~~ . Lindy van der Meulen December 1995. ABSTRACT This thesis introduces the reader to rock music in Durban from 1963 to 1985, tracing the development of rock in Durban from rock'n'roll to hard core punk. Although the thesis is historically orientated, it also endeavours to show the relationship of rock music in Durban to three central themes, viz: the relationship of rock in Durban to the socio-political realities of apartheid in South Africa; the role of women in local rock, and the identity crisis experienced by white, English-speaking South Africans. -

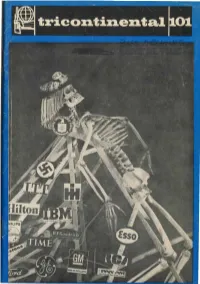

Elements FASCIST Relationship A

IPJtricontinental�01! Year XI - 1976 Published in Spanish, English, and French by the Executive Secretariat of the Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Africa, Asia and Latin America Tricontinental Bulletin authorizes the total or partial reproduction of its articles and information OSPAAAL P.O.B. 4224 Radiogram OSPAAAL Habana, Cuba summary URUGUAY-SOUTH 2 Elenients in a fascist AFRICA relationship UNITED STATES 9 The CIA., Washington and the transnationals Hector Danilo CHILE 22 Our faith is unshakable OAS 25 A. history of aggressions Susana Seleme PUERTO RICO LU Letter from a hero BRAZIL 44, A. challenge to censorship DEMOCRATIC 46 Constitution KAMPUCHEA 0 Appea Is and Messages SOUTH AFRICA 62 Why Soweto URUGUAY 64, Liberty for the political prisoners (�:x::x:::occc::ccx::o::::::iococcx:::,o::::;c::c::x::x:::x:::,:::)c::;cx:::x:...: J>�GiNA COURO Th,? econo�11ic policy can be summed up in the statement by the Minister of tl}a� legislation must be E co�om1cs blind and neutral toward foreign capital . d1stinc 1 an d practice no t on between it and domestic c apital." Pa_rallel to s thi policy of selling the country to foreign investors is th l elements a press1�n, ass ss cy 0 re a inatio . n and torture designed o s l � t i ence forever by physiiat�i'_ the voices that imina_ ion, FASCIST accuse the dictatorship. relationship Uruguay. a small country of 186 926 km� located in what is called the southern cone of the South American continent. flanked by Brazil and Argentina and with extensive bor ders along the Plata River, is suffering under an overtly fascist regime today.