Belarusian Protest: Regimes of Engagement and Coordination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

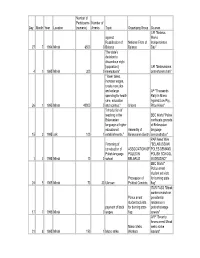

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

Review–Chronicle

REVIEWCHRONICLE of the human rights violations in Belarus in 2005 Human Rights Center Viasna ReviewChronicle » of the Human Rights Violations in Belarus in 2005 VIASNA « Human Rights Center Minsk 2006 1 REVIEWCHRONICLE of the human rights violations in Belarus in 2005 » VIASNA « Human Rights Center 2 Human Rights Center Viasna, 2006 REVIEWCHRONICLE of the human rights violations in Belarus in 2005 INTRODUCTION: main trends and generalizations The year of 2005 was marked by a considerable aggravation of the general situation in the field of human rights in Belarus. It was not only political rights » that were violated but social, economic and cultural rights as well. These viola- tions are constant and conditioned by the authoritys voluntary policy, with Lu- kashenka at its head. At the same time, human rights violations are not merely VIASNA a side-effect of the authoritarian state control; they are deliberately used as a « means of eradicating political opponents and creating an atmosphere of intimi- dation in the society. The negative dynamics is characterized by the growth of the number of victims of human rights violations and discrimination. Under these circums- tances, with a high level of latent violations and concealed facts, with great obstacles to human rights activity and overall fear in the society, the growth points to drastic stiffening of the regimes methods. Apart from the growing number of registered violations, one should men- Human Rights Center tion the increase of their new forms, caused in most cases by the development of the state oppressive machine, the expansion of legal restrictions and ad- ministrative control over social life and individuals. -

Int Cat Css Blr 30785 E

The Cost of Speaking Out Overview of human rights abuses committed by Belarusian authorities during peaceful protests in February-March 2017 © Truth Hounds Truth Hounds E [email protected] /facebook.com/truthhounds/ W truth-hounds.org IPHR - International Partnership for Human Rights Square de l'Aviation 7A 1070 Brussels, Belgium E [email protected] @IPHR W IPHRonline.org /facebook.com/iphronline CSP - Civic Solidarity Platform W civicsolidarity.org @CivicSolidarity /facebook.com/SivicSolidarity Crimea SOS E [email protected] /facebook.com/KRYM.SOS/ W krymsos.com Table of contents 1. Introduction and methodology 4 2. Chronological overview of events 5 2.1. February protests against the law on taxing the unemployed 5 2.2. March wave of administrative arrests of civil society activists and journalists 6 2.3. Increasing use of force by law enforcement officials 7 2.4. Criminal and administrative arrests prior to the 25 March Freedom Day protest in Minsk 9 2.5 Ill-treatment, excessive use of force and arbitrary detentions by police on 25 March - Freedom Day in Minsk 10 2.6 Raid of NGO HRC Viasna office and detention of 57 human rights defenders 14 2.7. Further arrests and reprisals by the authorities 14 2.8. Criminal cases related to allegations of attempted armed violence 16 3. Police use of force and arbitrary detentions during assemblies 17 3.1. International standards 17 3.2. Domestic legislation 18 3.2. Structure of the law enforcement services 19 3.4. Patterns of human rights abuses 19 4. Overview of concerns related to violations of freedom of assembly 20 4.1. -

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Article 6: Everyone has the right to recognition spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, everywhere as a person before the law. Article 7: All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimi- without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, nation to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination. Article 8: Everyone has the right to an effective rem- basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person edy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. by law. Article 9: No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security June 2011 564a Uladz Hrydzin © This report has been produced with the support of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). -

Situation of Human Rights in Belarus in 2012

Human Rights Center «Viasna» Situation of Human Rights in Belarus in 2012 REVIEW-CHRONICLE Мinsk, 2013 SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN BELARUS IN 2012 REVIEW-CHRONICLE Compiled by Tatsiana Reviaka Editing and introduction by Valiantsin Stefanovich The book was prepared on the basis of the monthly reviews of the situation of human rights in Belarus in 2012. Each of the monthly reviews includes the analysis of the most important events which influenced the observation of human rights for the given period, as well as the most evident and characteristic features of the abuses registered at that time. The review was prepared on the basis of personal applications of victims of human rights violations, the facts that were registered by human rigths defenders or voiced in open information sources. The book makes use of photos by Yuliya Darashkevich Dzmitry Bushko, Siarhei Hudzilin, Nastassia Loika, the web-sites http://photo.bymedia. net, http://nn.by, http://euroradio.fm, http://www.svaboda.org, http://volkovysk.by, http://gazetaby.com, http://mfront.net, http://www.reuters.com, http://belsat.eu/be, belhouse.org and the archive of the Human Rights Center «Viasna». TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 9 Review-Chronicle of Human Rights Violations in Belarus in January 2012 19 Politically motivated criminal prosecution 19 Harassment and pressurization of human rights activists and organizations 21 Torture and cruel treatment, poor conditions of detention 23 Death penalty 25 Administrative prosecution of social and political activists 25 Restrictions on freedom of speech 27 Restrictions on freedom of assembly 28 Situation of freedom of association 30 Review-Chronicle of Human Rights Violations in Belarus in February 2012 31 Political prisoners. -

SITUATION of HUMAN RIGHTS in BELARUS in 2014

Human Rights Centre “Viasna” SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS in BELARUS in 2014 REVIEW-CHRONICLE Minsk, 2015 SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN BELARUS in 2014 REVIEW-CHRONICLE Author and compiler: Tatsiana Reviaka Editor and author of the foreword: Valiantsin Stefanovich The edition was prepared on the basis of reviews of human rights violations in Belarus published every month in 2014. Each of the monthly reviews includes an analysis of the most important events infl uencing the observance of human rights and outlines the most eloquent and characteristic facts of human rights abuses registered over the described period. The review was prepared on the basis of personal appeals of victims of human rights abuses and the facts which were either registered by human rights activists or reported by open informational sources. The book features photos from the archive of the Human Rights Center “Viasna”, as well as from publications on the websites of Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty Belarus service, the Nasha Niva newspaper, tv.lrytas.lt, baj.by, gazetaby.com, and taken by Franak Viachorka and Siarhei Hudzilin. Human Rights Situation in 2014: Trends and Evaluation The situation of human rights during 2014 remained consistently poor with a tendency to deterioration at the end of the year. Human rights violations were of both systemic and systematic nature: basic civil and political rights were extremely restricted, there were no systemic changes in the fi eld of human rights (at the legislative level and (or) at the level of practices). The only positive development during the year was the early release of Ales Bialiatski, Chairman of the Human Rights Centre “Viasna” and Vice-President of the International Federation for Human Rights. -

National Awakening in Belarus: Elite Ideology to 'Nation' Practice

National Awakening in Belarus: Elite Ideology to 'Nation' Practice Tatsiana Kulakevich SAIS Review of International Affairs, Volume 40, Number 2, Summer-Fall 2020, pp. 97-110 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/783885 [ Access provided at 7 Mar 2021 23:30 GMT from University Of South Florida Libraries ] National Awakening in Belarus: Elite Ideology to ‘Nation’ Practice Tatsiana Kulakevich This article examines the formation of nationalism in Belarus through two dimensions: elite ideology and everyday practice. I argue the presidential election of 2020 turned into a fundamental institutional crisis when a homogeneous set of ‘nation’ practices against the state ideology replaced existing elite ideology. This resulted in popular incremental changes in conceptions of national understanding. After twenty-six consecutive years in power, President Lukashenka unintentionally unleashed a process of national awakening leading to the rise of a new sovereign nation that demands the right to determine its own future, independent of geopolitical pressures and interference. Introduction ugust 2020 witnessed a resurgence of nationalist discourse in Belarus. AUnlike in the Transatlantic world, where politicians articulate visions of their nations under siege—by immigrants, refugees, domestic minority popu- lations—narratives of national and political failure dominate in Belarus Unlike trends in the Transatlantic resonate with large segments of the voting public. -

Republic of Belarus

Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights REPUBLIC OF BELARUS EARLY PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 17 November 2019 ODIHR Election Observation Mission Final Report Warsaw 4 March 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ 2 II. INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ....................................................................... 5 III. BACKGROUND AND POLITICAL CONTEXT ........................................................................... 5 IV. ELECTORAL SYSTEM AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK .............................................................. 7 A. ELECTORAL SYSTEM ........................................................................................................................ 7 B. LEGAL FRAMEWORK ....................................................................................................................... 8 V. ELECTION ADMINISTRATION ................................................................................................... 9 VI. VOTER REGISTRATION .............................................................................................................. 11 VII. CANDIDATE REGISTRATION .................................................................................................... 12 VIII. ELECTION CAMPAIGN ............................................................................................................... 15 IX. CAMPAIGN FINANCE ................................................................................................................. -

2019 Parliamentary (ENG)

INTERNATIONAL ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION Republic of Belarus – Early Parliamentary Elections, 17 November 2019 STATEMENT OF PRELIMINARY FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS The 17 November early parliamentary elections proceeded calmly but did not meet important international standards for democratic elections. There was an overall disregard for fundamental freedoms of assembly, association and expression. A high number of candidates stood for election, but an overly restrictive registration process inhibited the participation of opposition. A limited amount of campaigning took place, within a restrictive environment that, overall, did not provide for a meaningful or competitive political contest. Media coverage of the campaign did not enable voters to receive sufficient information about contestants. The election administration was dominated by the executive authority, limiting its impartiality and independence, and the integrity of the election process was not adequately safeguarded. Significant procedural shortcomings during the counting of votes raised concerns about whether results were counted and reported honestly, and an overall lack of transparency reduced the opportunity for meaningful observation. The 110 members of the House of Representatives are elected for four-year terms across majoritarian districts. The elections were called by the president on 5 August, effectively dissolving the outgoing parliament approximately one year before the expiration of its mandate, without reference to any of the constitutional grounds for dissolution, contrary to OSCE commitments. The authorities maintained that the elections were not considered early under national law and were scheduled within the competency of the president. Overall, the legal framework does not adequately guarantee the conduct of elections in line with OSCE commitments and other international standards and obligations, underlying the need for a comprehensive and inclusive reform. -

Belarus by Alexei Pikulik, Dzianis Melyantsou Et Al

Belarus by Alexei Pikulik, Dzianis Melyantsou et al. Capital: Minsk Population: 9.5 million GNI/capita, PPP: US$14,460 Source: The data above are drawn from the World Bank’sWorld Development Indicators 2013. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Electoral Process 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 7.00 6.75 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 Civil Society 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.50 6.50 6.25 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.50 Independent Media 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 Governance* 6.50 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic Governance n/a 6.75 7.00 7.00 7.00 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Local Democratic Governance n/a 6.50 6.50 6.50 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 Judicial Framework and Independence 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 6.75 7.00 7.00 Corruption 5.75 6.00 6.25 6.25 6.25 6.00 6.00 6.00 6.25 6.25 Democracy Score 6.54 6.64 6.71 6.68 6.71 6.57 6.50 6.57 6.68 6.71 * Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects. -

CORRESPONDENCE Freedom for Nations! Freedom for Individuals!

GW ISSN 0001 — 0545 ABN B 20004 F CORRESPONDENCE Freedom for Nations! Freedom for Individuals! Verlagspostamt: Miinchen 2 January-February 1988 Vol. XXXIX No. CONTENTS: Eric Brodin 7 Decades Of Soviet Russian Empire.................................4 Glasnost And The Summit...................................................5 Bohdan Nahaylo Ukrainian Association Of Independent Creative Intelligentsia Formed............................................ 7 The Tragic Fate Of Vasyl Stus...........................................9 Mykola And Raissa Rudenko In The West....................... 13 Communique Of The VII Supreme Assembly Of The Organization Of Ukrainian Nationalists..........................18 Gregory Udod What Has Christianity Given To Ukraine During The First Millennium?....................................................... 22 Joint Communique Of The WACL And APACL Executive Committee Meeting..........................................31 Linda Shapiro The Victims Of Communism............................................. 33 Cao Thang Tran Denouncing The Viet Cong Extortion Scheme................ 35 News & Views.....................................................................37 From Behind The Iron Curtain..........................................42 Cover: Volodymyr the Great by Gregor Kruk. Freedom for Nations! Freedom for Individuals! ABN CORRESPONDENCE BULLETIN OF THE ANTI-BOLSHEVIK BLOC OF NATIONS Publisher and Owner (Verleger und It is not our practice to pay for contribut Inhaber): American Friends of the Anti- ed materials. -

BST-Vorlage 2013

PolicyBrief Policy Brief | 07.2017 The condition of NGOs and civil society in Belarus Veranika Laputska (in cooperation with Łukasz Wenerski) History and legal background various ages and social statuses, fell under this umbrella. This form of organization – a When in 1991 Belarus gained its “public association” – is still the most independence from the USSR, Belarusian popular type of a civil society organization civil society could be characterized as in Belarus. typical for a post-Soviet third sector. On the one hand, a large number of public On the other hand, some organizations associations had existed since Soviet originated from “informal” groups dating times, but they were in fact closely back to samizdat activities but later associated with the state and the established their associations, thanks to Communist Party, rather than with the the years of perestroika and glasnost. They population. This group comprised either were devoted to the revival of Belarusian pro-government or state-founded national traditions, culture and memory. organizations whose aim was to control Such organizations enjoyed prosperity and and influence state ideology, morality, and gained real popularity during the first years the upbringing and education of a of Belarus’s independence in the early maximum amount of Soviet citizens. To a years of the 1990s, whereas the first group great extent, practically all “public was facing an ideological crisis as the associations,” including those which communist ideology which used to unite operate in sports, culture and education and support them did not exist anymore. and involve the participation of people of NGOs and civil society in Belarus | page 2 The situation changed after the first Presidential Decree No.