OSW Commentary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

En En Amendments 1

European Parliament 2019-2024 Committee on Foreign Affairs 2020/2081(INI) 2.9.2020 AMENDMENTS 1 - 388 Draft report Petras Auštrevičius (PE652.398v01-00) Proposal for a Recommendation to the Council, the Commission and the Vice- President of the Commission/High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy on relations with Belarus (2020/2081(INI)) AM\1212303EN.docx PE657.166v01-00 EN United in diversityEN AM_Com_NonLegReport PE657.166v01-00 2/171 AM\1212303EN.docx EN Amendment 1 Viola Von Cramon-Taubadel on behalf of the Greens/EFA Group Motion for a resolution Citation 2 Motion for a resolution Amendment — having regard to the Council — having regard to the Council conclusions on Belarus of 15 February conclusions on Belarus of 15 February 2016, 2016 and the main outcomes of the video conference of Foreign Affairs Ministers of 14 August 2020, Or. en Amendment 2 Viola Von Cramon-Taubadel on behalf of the Greens/EFA Group Motion for a resolution Citation 2 a (new) Motion for a resolution Amendment — having regard to the Conclusions by the President of the European Council following the video conference of the members of the European Council on 19 August 2020, Or. en Amendment 3 Attila Ara-Kovács Motion for a resolution Citation 4 Motion for a resolution Amendment — having regard to the Joint — having regard to the Joint Declarations of the Eastern Partnership Declarations of the Eastern Partnership Summits of 2009 in Prague, 2011 in Summits of 2009 in Prague, 2011 in Warsaw, 2013 in Vilnius, 2015 in Riga and Warsaw, 2013 in Vilnius, 2015 in Riga, 2017 in Brussels, 2017 in Brussels and Eastern Partnership leaders' video conference in 2020, AM\1212303EN.docx 3/171 PE657.166v01-00 EN Or. -

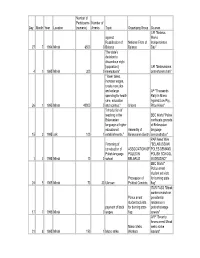

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

Evolution of the Belarusian National Movement in The

EVOLUTION OF THE BELARUSIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT IN THE PAGES OF PERIODICALS (1914-1917) By Aliaksandr Bystryk Submitted to Central European University Nationalism Studies Program In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Advisor: Professor Maria Kovacs Secondary advisor: Professor Alexei Miller CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2013 Abstract Belarusian national movement is usually characterised by its relative weakness delayed emergence and development. Being the weakest movement in the region, before the WWI, the activists of this movement mostly engaged in cultural and educational activities. However at the end of First World War Belarusian national elite actively engaged in political struggles happening in the territories of Western frontier of the Russian empire. Thus the aim of the thesis is to explain how the events and processes caused by WWI influenced the national movement. In order to accomplish this goal this thesis provides discourse and content analysis of three editions published by the Belarusian national activists: Nasha Niva (Our Field), Biełarus (The Belarusian) and Homan (The Clamour). The main findings of this paper suggest that the anticipation of dramatic social and political changes brought by the war urged national elite to foster national mobilisation through development of various organisations and structures directed to improve social cohesion within Belarusian population. Another important effect of the war was that a part of Belarusian national elite formulated certain ideas and narratives influenced by conditions of Ober-Ost which later became an integral part of Belarusian national ideology. CEU eTD Collection i Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1. Between krajowość and West-Russianism: The Development of the Belarusian National Movement Prior to WWI ..................................................................................................... -

Review–Chronicle

REVIEWCHRONICLE of the human rights violations in Belarus in 2005 Human Rights Center Viasna ReviewChronicle » of the Human Rights Violations in Belarus in 2005 VIASNA « Human Rights Center Minsk 2006 1 REVIEWCHRONICLE of the human rights violations in Belarus in 2005 » VIASNA « Human Rights Center 2 Human Rights Center Viasna, 2006 REVIEWCHRONICLE of the human rights violations in Belarus in 2005 INTRODUCTION: main trends and generalizations The year of 2005 was marked by a considerable aggravation of the general situation in the field of human rights in Belarus. It was not only political rights » that were violated but social, economic and cultural rights as well. These viola- tions are constant and conditioned by the authoritys voluntary policy, with Lu- kashenka at its head. At the same time, human rights violations are not merely VIASNA a side-effect of the authoritarian state control; they are deliberately used as a « means of eradicating political opponents and creating an atmosphere of intimi- dation in the society. The negative dynamics is characterized by the growth of the number of victims of human rights violations and discrimination. Under these circums- tances, with a high level of latent violations and concealed facts, with great obstacles to human rights activity and overall fear in the society, the growth points to drastic stiffening of the regimes methods. Apart from the growing number of registered violations, one should men- Human Rights Center tion the increase of their new forms, caused in most cases by the development of the state oppressive machine, the expansion of legal restrictions and ad- ministrative control over social life and individuals. -

Int Cat Css Blr 30785 E

The Cost of Speaking Out Overview of human rights abuses committed by Belarusian authorities during peaceful protests in February-March 2017 © Truth Hounds Truth Hounds E [email protected] /facebook.com/truthhounds/ W truth-hounds.org IPHR - International Partnership for Human Rights Square de l'Aviation 7A 1070 Brussels, Belgium E [email protected] @IPHR W IPHRonline.org /facebook.com/iphronline CSP - Civic Solidarity Platform W civicsolidarity.org @CivicSolidarity /facebook.com/SivicSolidarity Crimea SOS E [email protected] /facebook.com/KRYM.SOS/ W krymsos.com Table of contents 1. Introduction and methodology 4 2. Chronological overview of events 5 2.1. February protests against the law on taxing the unemployed 5 2.2. March wave of administrative arrests of civil society activists and journalists 6 2.3. Increasing use of force by law enforcement officials 7 2.4. Criminal and administrative arrests prior to the 25 March Freedom Day protest in Minsk 9 2.5 Ill-treatment, excessive use of force and arbitrary detentions by police on 25 March - Freedom Day in Minsk 10 2.6 Raid of NGO HRC Viasna office and detention of 57 human rights defenders 14 2.7. Further arrests and reprisals by the authorities 14 2.8. Criminal cases related to allegations of attempted armed violence 16 3. Police use of force and arbitrary detentions during assemblies 17 3.1. International standards 17 3.2. Domestic legislation 18 3.2. Structure of the law enforcement services 19 3.4. Patterns of human rights abuses 19 4. Overview of concerns related to violations of freedom of assembly 20 4.1. -

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election

BELARUS Restrictions on the Political and Civil Rights of Citizens Following the 2010 Presidential Election of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Article 6: Everyone has the right to recognition spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, everywhere as a person before the law. Article 7: All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimi- without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, nation to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination. Article 8: Everyone has the right to an effective rem- basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person edy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. by law. Article 9: No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security June 2011 564a Uladz Hrydzin © This report has been produced with the support of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). -

Situation of Human Rights in Belarus in 2012

Human Rights Center «Viasna» Situation of Human Rights in Belarus in 2012 REVIEW-CHRONICLE Мinsk, 2013 SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN BELARUS IN 2012 REVIEW-CHRONICLE Compiled by Tatsiana Reviaka Editing and introduction by Valiantsin Stefanovich The book was prepared on the basis of the monthly reviews of the situation of human rights in Belarus in 2012. Each of the monthly reviews includes the analysis of the most important events which influenced the observation of human rights for the given period, as well as the most evident and characteristic features of the abuses registered at that time. The review was prepared on the basis of personal applications of victims of human rights violations, the facts that were registered by human rigths defenders or voiced in open information sources. The book makes use of photos by Yuliya Darashkevich Dzmitry Bushko, Siarhei Hudzilin, Nastassia Loika, the web-sites http://photo.bymedia. net, http://nn.by, http://euroradio.fm, http://www.svaboda.org, http://volkovysk.by, http://gazetaby.com, http://mfront.net, http://www.reuters.com, http://belsat.eu/be, belhouse.org and the archive of the Human Rights Center «Viasna». TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 9 Review-Chronicle of Human Rights Violations in Belarus in January 2012 19 Politically motivated criminal prosecution 19 Harassment and pressurization of human rights activists and organizations 21 Torture and cruel treatment, poor conditions of detention 23 Death penalty 25 Administrative prosecution of social and political activists 25 Restrictions on freedom of speech 27 Restrictions on freedom of assembly 28 Situation of freedom of association 30 Review-Chronicle of Human Rights Violations in Belarus in February 2012 31 Political prisoners. -

The Baltic Sea Region the Baltic Sea

TTHEHE BBALALTTICIC SSEAEA RREGIONEGION Cultures,Cultures, Politics,Politics, SocietiesSocieties EditorEditor WitoldWitold MaciejewskiMaciejewski A Baltic University Publication Baltic and East Slavic languages; 17 Yiddish Sven Gustavsson 1. Language policies in the Russian Empire In the middle of the 17th century, when the Russian Empire had recovered from political unrest, it directed its expansionist efforts towards the west and southwest, towards the Swedish and the Polish-Lithuanian states. This expansion was completed with the Congress of Vienna in 1815. The situation only changed with the revolution in 1917 and the end of World War I. Then Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland became independent states. Poland also won back parts of its former possessions in Belarus and Ukraine. With World War II, the Soviet Union restored many of the former borders of the Russian empire, recapturing Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, the Polish parts of Ukraine and Belarus and also incorporating most of Eastern Prussia. The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 following the August coup reduced the empire’s area once again. Clearly, the history and the language policy of the Russian empire has had a great impact on the history of many of the languages and peoples in the Baltic area. A short overview is therefore appropriate here. Russification has been a part of Russian policy from the begin- ning. After Mazepa’s cooperation with the Swedish king Charles XII, all traces of Ukrainian autonomy promised in the Treaty of Perejaslavl of 1654 vanished. In 1720, even the printing of Ukrainian works was forbidden. In the Estonian and Latvian areas taken from Sweden in the Great Nordic War at the beginning of the 18th century, the Tsar, however, relied on the mostly German nobility who got extensive privileges. -

SITUATION of HUMAN RIGHTS in BELARUS in 2014

Human Rights Centre “Viasna” SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS in BELARUS in 2014 REVIEW-CHRONICLE Minsk, 2015 SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN BELARUS in 2014 REVIEW-CHRONICLE Author and compiler: Tatsiana Reviaka Editor and author of the foreword: Valiantsin Stefanovich The edition was prepared on the basis of reviews of human rights violations in Belarus published every month in 2014. Each of the monthly reviews includes an analysis of the most important events infl uencing the observance of human rights and outlines the most eloquent and characteristic facts of human rights abuses registered over the described period. The review was prepared on the basis of personal appeals of victims of human rights abuses and the facts which were either registered by human rights activists or reported by open informational sources. The book features photos from the archive of the Human Rights Center “Viasna”, as well as from publications on the websites of Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty Belarus service, the Nasha Niva newspaper, tv.lrytas.lt, baj.by, gazetaby.com, and taken by Franak Viachorka and Siarhei Hudzilin. Human Rights Situation in 2014: Trends and Evaluation The situation of human rights during 2014 remained consistently poor with a tendency to deterioration at the end of the year. Human rights violations were of both systemic and systematic nature: basic civil and political rights were extremely restricted, there were no systemic changes in the fi eld of human rights (at the legislative level and (or) at the level of practices). The only positive development during the year was the early release of Ales Bialiatski, Chairman of the Human Rights Centre “Viasna” and Vice-President of the International Federation for Human Rights. -

National Awakening in Belarus: Elite Ideology to 'Nation' Practice

National Awakening in Belarus: Elite Ideology to 'Nation' Practice Tatsiana Kulakevich SAIS Review of International Affairs, Volume 40, Number 2, Summer-Fall 2020, pp. 97-110 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/783885 [ Access provided at 7 Mar 2021 23:30 GMT from University Of South Florida Libraries ] National Awakening in Belarus: Elite Ideology to ‘Nation’ Practice Tatsiana Kulakevich This article examines the formation of nationalism in Belarus through two dimensions: elite ideology and everyday practice. I argue the presidential election of 2020 turned into a fundamental institutional crisis when a homogeneous set of ‘nation’ practices against the state ideology replaced existing elite ideology. This resulted in popular incremental changes in conceptions of national understanding. After twenty-six consecutive years in power, President Lukashenka unintentionally unleashed a process of national awakening leading to the rise of a new sovereign nation that demands the right to determine its own future, independent of geopolitical pressures and interference. Introduction ugust 2020 witnessed a resurgence of nationalist discourse in Belarus. AUnlike in the Transatlantic world, where politicians articulate visions of their nations under siege—by immigrants, refugees, domestic minority popu- lations—narratives of national and political failure dominate in Belarus Unlike trends in the Transatlantic resonate with large segments of the voting public. -

Culture and Change in Belarus

East European Reflection Group (EE RG) Identifying Cultural Actors of Change in Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova Culture and Change in Belarus Report prepared by Yael Ohana, Rapporteur Generale Bratislava, August 2007 Culture and Change in Belarus “Life begins for the counter-culture in Belarus after regime change”. Anonymous, at the consultation meeting in Kiev, Ukraine, June 14 2007. Introduction1 Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine have recently become direct neighbours of the European Union. Both Moldova and Ukraine have also become closer partners of the European Union through the European Neighbourhood Policy. Neighbourhood usually refers to people next-door, people we know, or could easily get to know. It implies interest, curiosity and solidarity in the other living close by. For the moment, the European Union’s “neighbourhood” is something of an abstract notion, lacking in substance. In order to avoid ending up “lost in translation”, it is necessary to question and some of the basic premises on which cultural and other forms of European cooperation are posited. In an effort to create constructive dialogue with this little known neighbourhood, the European Cultural Foundation (ECF) and the German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF) are currently preparing a three- year partnership to support cultural agents of change in Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine. In the broad sense, this programme is to work with, and provide assistance to, initiatives and institutions that employ creative, artistic and cultural means to contribute to the process of constructive change in each of the three countries. ECF and GMF have begun a process of reflection in order to understand the extent to which the culture sphere in each of the three countries under consideration can support change, defined here as processes and dynamics contributing to democratisation, Europeanisation and modernisation in the three countries concerned. -

National Identity Against External Pressure

Source: © Vasily Fedosenko, Reuters. Fedosenko, Vasily © Source: Nationalism National Identity Against External Pressure Will Belarus Reconcile Its Contradicting Narratives? Jakob Wöllenstein 26 Viewed dispassionately, the pro-Russian and pro-European poles of the Belarusian national identity, however much they disagree in questions of content, are both part of Belarus in its modern form. From the identity politics perspective, this realisation represents an opportunity to reconcile internal narratives and resolve internal tensions. This insight can ultimately lead to the heightening of the country’s profile at the international level – especially in the West, where Belarus is still often perceived as a mere Russian appendage because of the way it has positioned itself for years. A Hero’s Funeral demonstratively, not the most senior, since Pres- ident Aliaksandr Lukashenka was presiding over 22 November 2019 was a cold, windy day in Vil- regional agricultural deliberations at the time.1 nius, Lithuania. Yet the crowd that had gathered His compatriots, meanwhile, had travelled to in front of the cathedral welcomed the gusts. Vilnius and consciously assembled not under the They proudly held up their flags and the squared official red-green national flag, but under the his- blazed white and red – the most common motif torical flag from the early 1990s, which in turn was the old Belarusian flag with its red stripe on refers back to the short-lived Belarusian People’s a white field. The occasion of the gathering was a Republic ( BNR) of 1918