PLANOFACTION Resilient Livelihoods for Agriculture And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARKET SYSTEM ASSESSMENT for the DAIRY VALUE CHAIN Irbid & Mafraq Governorates, Jordan MARCH 2017

Photo Credit: Mercy Corps MARKET SYSTEM ASSESSMENT FOR THE DAIRY VALUE CHAIN Irbid & Mafraq Governorates, Jordan MARCH 2017 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 METHODOLOGY 4 TARGET POPULATION 4 JUSTIFICATION FOR MARKET SELECTION 4 AREA OVERVIEW 5 MARKET SYSTEM MAP 9 CONSUMPTION & DEMAND ANALYSIS 9 SUPPLY ANALYSIS & PRODUCTION POTENTIAL 12 TRADE FLOWS 14 MARGINS ANALYSIS 15 SEASONAL CALENDAR 15 BUSINESS ENABLING ENVIRONMENT 17 OTHER INITATIVES 20 KEY FACTORS DRIVING CHANGE IN THE MARKET 21 RECOMMENDATIONS & SUGGESTED INTERVENTIONS 21 MERCY CORPS Market System Assessment for the Dairy Value Chain: Irbid & Mafraq 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The dairy industry plays an important role in the economy of Jordan. In the early 70’s, Jordan established programmes to promote dairy farming - new breeds of more productive dairy cows were imported, farmers learned to comply with top industry operating standards, and the latest technologies in processing, packaging and distribution were introduced. Today there are 25 large dairy companies across Jordan. However inefficient production techniques, scarce water and feed resources and limited access to veterinary care have limited overall growth. While milk production continues to steadily increase—with 462,000 MT produced (78% of the market demand) in 2015 according to the Ministry of Agriculture—the country is well below the production levels required for self-sufficiency. The initial focus of the assessment was on cow milk, however sheep and goat milk were discovered to play a more important role in livelihoods of poor households, and therefore they were included during the course of the assessment. Sheep and goats are better adapted to a semi-arid climate, and sheep represent about 66 percent of livestock in Jordan. -

Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land : the Case of Azraq Basin

Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land: The case of Azraq Basin, Jordan of Azraq in Arid Land: The case Agriculture Groundwater-Based Majd Al Naber Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land: The case of Azraq Basin, Jordan Majd Al Naber Propositions: 1. Indirect regulatory measures are more efficient than direct measures in controlling the use of groundwater resources. (this thesis) 2. Decreasing the accessibility to production factors constrains, but does not fully control, groundwater-based agriculture expansion. (this thesis) 3. Remote sensing technology should be used in daily practice to monitor environmental changes. 4. Irreversible changes are more common than reversible ones in cases of over exploitation of natural resources. 5. A doctorate title is not the achievement of one's life, but a stepping-stone to one's future. 6. Positivity is required to deal with the long Ph.D. journey. Propositions belonging to the thesis, entitled Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land: The Case of Azraq Basin, Jordan Majd Al Naber Wageningen, 10 April 2018 Groundwater-Based Agriculture in Arid Land: The Case of Azraq Basin, Jordan Majd Al Naber Thesis committee Promotors Prof. Dr J. Wallinga Professor of Soil and Landscape Wageningen University & Research Co-promotor Dr F. Molle Senior Researcher, G-Eau Research Unit Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, Montpellier, France Dr Ir J. J. Stoorvogel Associate Professor, Soil Geography and Landscape Wageningen University & Research Other members Prof. Dr Ir P.J.G.J. Hellegers, Wageningen University & Research Prof. Dr Olivier Petit, Université d'Artois, France Prof. Dr Ir P. van der Zaag, IHE Delft University Dr Ir J. -

26Thmarch Part1 Executive Summary

End of Project Evaluation for Jordan National Red Crescent Society (JNRCS) Community Based Health and First Aid (CBHFA) and Psychosocial Support project in Jordan EVALUATION REPORT February – March 2017 Evaluator: Ofelia García This evaluation was produced at the request of the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Ofelia García, independent consultant, led the evaluation exercise and is the author of this report. DISCLAIMER The author's views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies or the Jordan Red Crescent Society. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.A Evaluation Purpose and Scope 1.B Intervention’s Background 1.C Methodology – Overall Orientation 1.D Conclusions 1.E. Recommendations 2. EVALUATION PURPOSE & EVALUATION QUESTIONS page 1 2.A Evaluation Purpose and Scope 2.B Evaluation Questions 3. BACKGROUND page 3 3.A Context 3.B Intervention’s Background 3.C Intervention’s Evolution 4. EVALUATION METHODS & LIMITATIONS page 12 4.A Timeline – Phases and Deliverables of the Evaluation 4.B Methodology – Overall Orientation 4.C Limitations 5. FINDINGS page 15 5.A. Relevance and Appropriateness 5.B. Targeting and Coverage 5.C. Effectiveness 5.D. Efficiency 5.E. Connectedness 6. CONCLUSIONS page 43 7. RECOMMENDATIONS page 47 ANNEXES ANNEX I: Terms of Reference ANNEX II: JHAS /UNHCR Hospitals ANNEX III: List of Consulted Documents - Bibliography ANNEX IV: List of contacted Key Informants -

Chapter 4 Allocated Water to Irbid and Ramtha

CHAPTER 4 ALLOCATED WATER TO IRBID AND RAMTHA With fixed available water resource for the northern governorates in future, allocated water to the Study Area (Irbid and Ramtha) is estimated in this Chapter. Allocation is made based on sub-transmission zones first and then to the Study Area because water transfer based on water allocation will be made through main transmission line and sub-transmission line. Population and water demand in the northern governorates is estimated and distributed to each locality in the northern governorates. Then, allocated water to the Study Area is estimated. Based on allocated water, distribution facilities in the Study Area are planned in the following Chapters. The sub-transmission lines are defined as branch lines from the main transmission line. Sub-transmission zones are defined as water supply zones to which water is supplied from sub-transmission lines. 4.1 Water Demand Estimation in Northern Governorates 4.1.1 Population (1) Population by Governorate Population estimated by Department of Statistics (DOS) is used in this Study. DOS estimates governorate population with different growth rates; low growth rate in Amman and Irbid governorates and high growth rates in Mafraq, Jerash and Ajloun governorates. The estimated population for the northern governorates up to 2035 is shown in Table 4.1 and Figure 4.1. The estimated populations in the governorates are almost the same as used in the Water Reallocation Strategy 2010 where estimated populations in 2035 are 1.81 million in Irbid, 0.23 million in Ajloun, 0.31 million in Jerash and 0.48 million in Mafraq, totaling to 2.83 million. -

Chapter IV: the Implications of the Crisis on Host Communities in Irbid

Chapter IV The Implications of the Crisis on Host Communities in Irbid and Mafraq – A Socio-Economic Perspective With the beginning of the first quarter of 2011, Syrian refugees poured into Jordan, fleeing the instability of their country in the wake of the Arab Spring. Throughout the two years that followed, their numbers doubled and had a clear impact on the bor- dering governorates, namely Mafraq and Irbid, which share a border with Syria ex- tending some 375 kilometers and which host the largest portion of refugees. Official statistics estimated that at the end of 2013 there were around 600,000 refugees, of whom 170,881 and 124,624 were hosted by the local communities of Mafraq and Ir- bid, respectively. This means that the two governorates are hosting around half of the UNHCR-registered refugees in Jordan. The accompanying official financial burden on Jordan, as estimated by some inter- national studies, stood at around US$2.1 billion in 2013 and is expected to hit US$3.2 billion in 2014. This chapter discusses the socio-economic impact of Syrian refugees on the host communities in both governorates. Relevant data has been derived from those studies conducted for the same purpose, in addition to field visits conducted by the research team and interviews conducted with those in charge, local community members and some refugees in these two governorates. 1. Overview of Mafraq and Irbid Governorates It is relevant to give a brief account of the administrative structure, demographics and financial conditions of the two governorates. Mafraq Governorate Mafraq governorate is situated in the north-eastern part of the Kingdom and it borders Iraq (east and north), Syria (north) and Saudi Arabia (south and east). -

Solid Waste Value Chain Analysis Irbid and Mafraq Jordan

SOLID WASTE VALUE CHAIN ANALYSIS IRBID AND MAFRAQ JORDAN Mitigating the Impact of the Syrian Refugee Crisis on Jordanian Vulnerable Host Communities for UNDP Jordan June 2015 Solid Waste Value Chain Analysis Final Report Irbid and Mafraq – Jordan June 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... III LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................................IV LIST OF ANNEXES .......................................................................................................................V LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ..........................................................................................................VI 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Waste Generation and Management ......................................................................... 1 1.2 Solid Waste Actors ...................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Solid Waste Value Chains ............................................................................................ 2 1.4 Solid Waste Trends ...................................................................................................... 2 1.5 Solid Waste Intervention Recommendations ............................................................. 3 1.6 Conclusion -

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( in Jds ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO

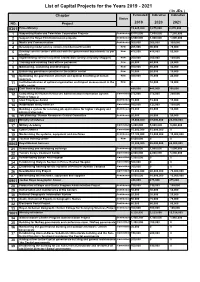

List of Capital Projects for the Years 2019 - 2021 ( In JDs ) Chapter Estimated Indicative Indicative Status NO. Project 2019 2020 2021 0301 Prime Ministry 13,625,000 9,875,000 8,870,000 1 Supporting Radio and Television Corporation Projects Continuous 8,515,000 7,650,000 7,250,000 2 Support the Royal Film Commission projects Continuous 3,500,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 3 Media and Communication Continuous 300,000 300,000 300,000 4 Developing model service centers (middle/nourth/south) New 205,000 90,000 70,000 5 Develop service centers affiliated with the government departments as per New 475,000 415,000 50,000 priorities 6 Implementing service recipients satisfaction surveys (mystery shopper) New 200,000 200,000 100,000 7 Training and enabling front offices personnel New 20,000 40,000 20,000 8 Maintaining, sustaining and developing New 100,000 80,000 40,000 9 Enhancing governance practice in the publuc sector New 10,000 20,000 10,000 10 Optimizing the government structure and optimal benefiting of human New 300,000 70,000 20,000 resources 11 Institutionalization of optimal organization and impact measurement in the New 0 10,000 10,000 public sector 0601 Civil Service Bureau 485,000 445,000 395,000 12 Completing the Human Resources Administration Information System Committed 275,000 275,000 250,000 Project/ Stage 2 13 Ideal Employee Award Continuous 15,000 15,000 15,000 14 Automation and E-services Committed 160,000 125,000 100,000 15 Building a system for receiving job applications for higher category and Continuous 15,000 10,000 10,000 administrative jobs. -

A Sociolinguistic Study in Am, Northern Jordan

A Sociolinguistic Study in am, Northern Jordan Noora Abu Ain A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Language and Linguistics University of Essex June 2016 2 To my beloved Ibrahim for his love, patience and continuous support 3 Abstract T features in S J T (U) T J : zubde „ ‟ dʒubne „ ‟. On the other hand, the central and southern Jordanian dialects have [i] in similar environments; thus, zibde and dʒibne T (L) T the dark varian t [l] I , : x „ ‟ g „ ‟, other dialects realise it as [l], and thus: x l and g l. These variables are studied in relation to three social factors (age, gender and amount of contact) and three linguistic factors (position in syllable, preceding and following environments). The sample consists of 60 speakers (30 males and 30 females) from three age groups (young, middle and old). The data were collected through sociolinguistic interviews, and analysed within the framework of the Variationist Paradigm using Rbrul statistical package. The results show considerable variation and change in progress in the use of both variables, constrained by linguistic and social factors. , T lowed by a back vowel. For both variables, the young female speakers were found to lead the change towards the non-local variants [i] and [l]. The interpretations of the findings focus on changes that the local community have experienced 4 as a result of urbanisation and increased access to the target features through contact with outside communities. Keywords: Jordan, , variable (U), variable (L), Rbrul, variation and change 5 Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... -

To Learn More About Our Activities in Jordan, Download This PDF

W OVERVIE JORDAN FACTS AND FIGURES 2020 JANUARY – DECEMBER 2020 SUMMARY The year 2020 has been one of uncommon challenges. In Jordan, despite measures imposed to curtail the spread of COVID-19, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) continued its work and maintained its humanitarian activities in several Governorates in the country. ICRC teams were able to support measures aimed at preventing the spread of COVID-19 especially in places of detention. Furthermore, the ICRC provided support to some families of missing persons; supported vulnerable Syrian refugees as well as host communities through livelihood projects and rehabilitated water infrastructure, while it equally trained engineers and operators to run them to ensure that host communities and Syrian refugees gain access to clean water. Some of these activities were carried out in partnership with the Jordan Red Crescent Society (JRCS), to whom we provided technical and material support to enable the JRCS deliver its humanitarian services more effectively, including in its COVID-19 response. One key aspect of our activities was the provision of equipment and facilities to the JRCS hospital. To strengthen the capacity of the health system in the management of COVID-19 infections, the ICRC provided Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and some medical supplies, while it offered training to some medical professionals on how best to respond to emergencies and enhance capacity in physical rehabilitation and provision of healthcare in detention. Consistent with its obligations to promote knowledge of International Humanitarian Law (IHL), the ICRC provided training for members of the Armed and Security Forces in Jordan and participating officers of the Police, Gendarmerie and Civil Defence (PSD), in addition to convening roundtable discussions towards raising awareness on a variety of humanitarian issues with civil society and the media. -

Jordan Middle East DISCUSSION PAPER and North Africa Transition Fund September 2017 Middle East and North Africa Transition Fund

Towards a new partnership between government and youth in Jordan Middle East DISCUSSION PAPER and North Africa Transition Fund September 2017 Middle East and North Africa Transition Fund ABOUT THE OECD MENA TRANSITION FUND OF THE DEAUVILLE PARTNERSHIP The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is an international body that promotes In May 2011, the Deauville Partnership was launched as a policies to improve the economic and social well-being long-term global initiative that provides Arab countries in of people around the world. It is made up of 35 member transition with a framework based on technical support countries, a secretariat in Paris, and a committee, drawn to strengthen governance for transparent, accountable from experts from government and other fields, for each governments and to provide an economic framework for work area covered by the organisation. The OECD provides sustainable and inclusive growth. a forum in which governments can work together to share experiences and seek solutions to common problems. We The Deauville Partnership has committed to support collaborate with governments to understand what drives Egypt, Jordan, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia and Yemen and the economic, social and environmental change. We measure Transition Fund is one of the levers to implement this productivity and global flows of trade and investment. commitment. The Transition Fund demonstrates a joint commitment by G7 members, Gulf and regional partners, For more information, please visit www.oecd.org. and international and regional financial institutions to support the efforts of the people and governments of the Partnership countries as they overhaul their economic systems to promote more accountable governance, broad- based, sustainable growth, and greater employment opportunities for youth and women. -

MA6-45 6.4.1 Quality of Brackish Water

6.4 Proposed Desalination Facilities----------------------------------------------MA6-45 6.4.1 Quality of Brackish Water and Seawater--------------------------------MA6-46 6.4.2 Quality of the Treated Water----------------------------------------------MA6-46 6.4.3 Applicable Treatment Process--------------------------------------------MA6-47 6.4.4 Development Plans---------------------------------------------------------MA6-48 6.4.4.1 Aqaba Seawater Desalination Development Plan------------------ MA6-48 6.4.4.2 Alternative Plan of Brackish Groundwater Development Plan---MA6-49 6.4.4.3 Selection of the Brackish Water Development---------------------- MA6-52 6.4.5 Preliminary Design of Aqaba Seawater Desalination Project-------- MA6-52 6.4.6 Preliminary Design of the Brackish Groundwater------------------------ MA6-57 Development Project 6.4.7 Proposed Implementation Schedule--------------------------------------MA6-62 6.5 UFW Improvement Measures-------------------------------------------------MA6-66 6.5.1 Definition of UFW----------------------------------------------------------MA6-66 6.5.2 Current Situation of UFW-------------------------------------------------MA6-66 6.5.2.1 Current Situation--------------------------------------------------------MA6-66 6.5.2.2 Problems to be Solved--------------------------------------------------MA6-67 6.5.3 Improvement Measures for UFW----------------------------------------MA6-67 6.5.3.1 Considerations for UFW Improvement Plan------------------------ MA6-67 6.5.3.2 UFW Improvement Plan-----------------------------------------------MA6-69 -

Syrian Refugees in Host Communities

Syrian Refugees in Host Communities Key Informant Interviews / District Profiling January 2014 This project has been implemented with the support of: Syrian Refugees in Host Communities: Key Informant Interviews and District Profiling January 2014 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY As the Syrian crisis extends into its third year, the number of Syrian refugees in Jordan continues to increase with the vast majority living in host communities outside of planned camps.1 This assessment was undertaken to gain an in-depth understanding of issues related to sector specific and municipal services. In total, 1,445 in-depth interviews were conducted in September and October 2013 with key informants who were identified as knowledgeable about the 446 surveyed communities. The information collected is disaggregated by key characteristics including access to essential services by Syrian refugees, and underlying factors such as the type and location of their shelters. This project was carried out to inform more effective humanitarian planning and interventions which target the needs of Syrian refugees in Jordanian host communities. The study provides a multi-sector profile for the 19 districts of northern Jordan where the majority of Syrian refugees reside2, focusing on access to municipal and other essential services by Syrian refugees, including primary access to basic services; barriers to accessing social services; trends over time; and the prioritised needs of refugees by sector. The project is funded by the British Embassy of Amman with the support of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The greatest challenge faced by Syrian refugees is access to cash, specifically cash for rent, followed by access to food assistance and non-food items for the winter season.