The Ancient History Teachings for Children Reflected in the ’80S Comics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Romanization of Romania: a Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage Colleen Ann Lovely Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2016 The Romanization of Romania: A Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage Colleen Ann Lovely Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Lovely, Colleen Ann, "The Romanization of Romania: A Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage" (2016). Honors Theses. 178. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/178 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Romanization of Romania: A Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage By Colleen Ann Lovely ********* Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Departments of Classics and Anthropology UNION COLLEGE March 2016 Abstract LOVELY, COLLEEN ANN The Romanization of Romania: A Look at the Influence of the Roman Military on Romanian History and Heritage. Departments of Classics and Anthropology, March 2016. ADVISORS: Professor Stacie Raucci, Professor Robert Samet This thesis looks at the Roman military and how it was the driving force which spread Roman culture. The Roman military stabilized regions, providing protection and security for regions to develop culturally and economically. Roman soldiers brought with them their native cultures, languages, and religions, which spread through their interactions and connections with local peoples and the communities in which they were stationed. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Katalog Zur Ausstellung "60 Jahre Marvel

Liebe Kulturfreund*innen, bereits seit Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs befasst sich das Amerikahaus München mit US- amerikanischer Kultur. Als US-amerikanische Behörde war es zunächst für seine Bibliothek und seinen Lesesaal bekannt. Doch schon bald wurde das Programm des Amerikahauses durch Konzerte, Filmvorführungen und Vorträge ergänzt. Im Jahr 1957 zog das Amerika- haus in sein heutiges charakteristisches Gebäude ein und ist dort, nach einer vierjährigen Generalsanierung, seit letztem Jahr wieder zu finden. 2014 gründete sich die Stiftung Bay- erisches Amerikahaus, deren Träger der Freistaat Bayern ist. Heute bietet das Amerikahaus der Münchner Gesellschaft und über die Stadt- und Landesgrenzen hinaus ein vielfältiges Programm zu Themen rund um die transatlantischen Beziehungen – die Vereinigten Staaten, Kanada und Lateinamerika- und dem Schwerpunkt Demokratie an. Unsere einladenden Aus- stellungräume geben uns die Möglichkeit, Werke herausragender Künstler*innen zu zeigen. Mit dem Comicfestival München verbindet das Amerikahaus eine langjährige Partnerschaft. Wir freuen uns sehr, dass wir mit der Ausstellung „60 Jahre Marvel Comics Universe“ bereits die fünfte Ausstellung im Rahmen des Comicfestivals bei uns im Haus zeigen können. In der Vergangenheit haben wir mit unseren Ausstellungen einzelne Comickünstler, wie Tom Bunk, Robert Crumb oder Denis Kitchen gewürdigt. Vor zwei Jahren freute sich unser Publikum über die Ausstellung „80 Jahre Batman“. Dieses Jahr schließen wir mit einem weiteren Jubiläum an und feiern das 60-jährige Bestehen des Marvel-Verlags. Im Mainstream sind die Marvel- Helden durch die in den letzten Jahren immer beliebter gewordenen Blockbuster bekannt geworden, doch Spider-Man & Co. gab es schon lange davor. Das Comic-Heft „Fantastic Four #1“ gab vor 60 Jahren den Startschuss des legendären Marvel-Universums. -

Dancing Through the City and Beyond: Lives, Movements and Performances in a Romanian Urban Folk Ensemble

Dancing through the city and beyond: Lives, movements and performances in a Romanian urban folk ensemble Submitted to University College London (UCL) School of Slavonic and East European Studies In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) By Elizabeth Sara Mellish 2013 1 I, Elizabeth Sara Mellish, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: 2 Abstract This thesis investigates the lives, movements and performances of dancers in a Romanian urban folk ensemble from an anthropological perspective. Drawing on an extended period of fieldwork in the Romanian city of Timi şoara, it gives an inside view of participation in organised cultural performances involving a local way of moving, in an area with an on-going interest in local and regional identity. It proposes that twenty- first century regional identities in southeastern Europe and beyond, can be manifested through participation in performances of local dance, music and song and by doing so, it reveals that the experiences of dancers has the potential to uncover deeper understandings of contemporary socio-political changes. This micro-study of collective behaviour, dance knowledge acquisition and performance training of ensemble dancers in Timi şoara enhances the understanding of the culture of dance and dancers within similar ensembles and dance groups in other locations. Through an investigation of the micro aspects of dancers’ lives, both on stage in the front region, and off stage in the back region, it explores connections between local dance performances, their participants, and locality and the city. -

Superman / Wonder Woman: Power Couple Volume 1 Free

FREE SUPERMAN / WONDER WOMAN: POWER COUPLE VOLUME 1 PDF Tony S. Daniel,Charles Soule | 176 pages | 30 Sep 2014 | DC Comics | 9781401248987 | English | United States Superman and Wonder Woman, Vol Power Couple : All About Romance % Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Tony S. Daniel Penciller. Paulo Siqueira Penciller. Eddie Barrows Penciller. Barry Kitson Artist. Matt Banning Inker. Sandu Florea Inker. Eber Ferreira Inker. Tomeu Morey Colourist. Carlos M. Mangual Letterer. Daniel Batman to tell the tale of a romance that will shake the stars themselves. These two super-beings love each other, but not everyone shares their joy. Some fear it, some test it-and some will try to kill for it. Some say love is a battlefield, but where Superman and Wonder Woman are concerned it spells Doomsday! Get A Copy. Hardcoverpages. More Details Original Title. Wonder WomanSuperman. Other Editions 8. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. Want happens nets in the book? Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Superman / Wonder Woman: Power Couple Volume 1 Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Jun 24, Anne rated it it was amazing Shelves: read-incomicsarcnetgalleygraphic-novels. Fuck me. No, seriously. I want Superman to fuck me. He's H-O-T! Yeah, yeah. I know what you're thinking. -

Roman Population Size: the Logic of the Debate

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics Roman population size: the logic of the debate Version 2.0 July 2007 Walter Scheidel Stanford University Abstract: This paper provides a critical assessment of the current state of the debate about the number of Roman citizens and the size of the population of Roman Italy. Rather than trying to make a case for a particular reading of the evidence, it aims to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of rival approaches and examine the validity of existing arguments and critiques. After a brief survey of the evidence and the principal positions of modern scholarship, it focuses on a number of salient issues such as urbanization, military service, labor markets, political stability, living standards, and carrying capacity, and considers the significance of field surveys and comparative demographic evidence. © Walter Scheidel. [email protected] 1 1. Roman population size: why it matters Our ignorance of ancient population numbers is one of the biggest obstacles to our understanding of Roman history. After generations of prolific scholarship, we still do not know how many people inhabited Roman Italy and the Mediterranean at any given point in time. When I say ‘we do not know’ I do not simply mean that we lack numbers that are both precise and safely known to be accurate: that would surely be an unreasonably high standard to apply to any pre-modern society. What I mean is that even the appropriate order of magnitude remains a matter of intense dispute. This uncertainty profoundly affects modern reconstructions of Roman history in two ways. First of all, our estimates of overall Italian population number are to a large extent a direct function of our views on the size of the Roman citizenry, and inevitably shape any broader guesses concerning the demography of the Roman empire as a whole. -

7 the Roman Empire

Eli J. S. Weaverdyck 7 The Roman Empire I Introduction The Roman Empire was one of the largest and longest lasting of all the empires in the ancient world.1 At its height, it controlled the entire coast of the Mediterranean and vast continental hinterlands, including most of western Europe and Great Brit- ain, the Balkans, all of Asia Minor, the Near East as far as the Euphrates (and be- yond, briefly), and northern Africa as far south as the Sahara. The Mediterranean, known to the Romans as mare nostrum(‘our sea’), formed the core. The Mediterranean basin is characterized by extreme variability across both space and time. Geologically, the area is a large subduction zone between the African and European tectonic plates. This not only produces volcanic and seismic activity, it also means that the most commonly encountered bedrock is uplifted limestone, which is easily eroded by water. Much of the coastline is mountainous with deep river valleys. This rugged topography means that even broadly similar climatic conditions can pro- duce drastically dissimilar microclimates within very short distances. In addition, strong interannual variability in precipitation means that local food shortages were an endemic feature of Mediterranean agriculture. In combination, this temporal and spatial variability meant that risk-buffering mechanisms including diversification, storage, and distribution of goods played an important role in ancient Mediterranean survival strategies. Connectivity has always characterized the Mediterranean.2 While geography encouraged mobility, the empire accelerated that tendency, inducing the transfer of people, goods, and ideas on a scale never seen before.3 This mobility, combined with increased demand and the efforts of the imperial govern- ment to mobilize specific products, led to the rise of broad regional specializations, particularly in staple foods and precious metals.4 The results of this increased con- It has also been the subject of more scholarship than any other empire treated in this volume. -

Narratives of Contamination and Mutation in Literatures of the Anthropocene Dissertation Presented in Partial

Radiant Beings: Narratives of Contamination and Mutation in Literatures of the Anthropocene Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kristin Michelle Ferebee Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2019 Dissertation Committee Dr. Thomas S. Davis, Advisor Dr. Jared Gardner Dr. Brian McHale Dr. Rebekah Sheldon 1 Copyrighted by Kristin Michelle Ferebee 2019 2 Abstract The Anthropocene era— a term put forward to differentiate the timespan in which human activity has left a geological mark on the Earth, and which is most often now applied to what J.R. McNeill labels the post-1945 “Great Acceleration”— has seen a proliferation of narratives that center around questions of radioactive, toxic, and other bodily contamination and this contamination’s potential effects. Across literature, memoir, comics, television, and film, these narratives play out the cultural anxieties of a world that is itself increasingly figured as contaminated. In this dissertation, I read examples of these narratives as suggesting that behind these anxieties lies a more central anxiety concerning the sustainability of Western liberal humanism and its foundational human figure. Without celebrating contamination, I argue that the very concept of what it means to be “contaminated” must be rethought, as representations of the contaminated body shape and shaped by a nervous policing of what counts as “human.” To this end, I offer a strategy of posthuman/ist reading that draws on new materialist approaches from the Environmental Humanities, and mobilize this strategy to highlight the ways in which narratives of contamination from Marvel Comics to memoir are already rejecting the problematic ideology of the human and envisioning what might come next. -

Chapter 34 Territory Controlled by Rome, About 264 B.C.E

CHAPTER is Rome grew into a huge empire, power fell into the hands of a single supreme ruler. From Republic to Empire 34.1 Introduction In the last chapter, you learned how Rome became a republic. In this chapter, you'll discover how the republic grew into a mighty empire that ruled the entire Mediterranean world. The expansion of Roman power took place over about 500 years, from 509 B.C.H. to 14 C.E. At the start of this period, Rome was a tiny republic in central Italy. Five hundred years later, it was a thriving center of a vast empire. At its height, the Roman Empire included most of Europe together with North Africa, Egypt, Syria, and Asia Minor. The growth in Rome's power happened gradually, and it came at a price. Romans had to fight countless wars to defend their growing territory and to conquer new lands. Along the way, Rome itself changed. Romans had once been proud to be gov- erned by elected leaders. Their heroes were men who had helped to preserve the republic. By 14 C.E., the republic was just a memory. Power was in the hands of a single supreme ruler, the emperor. Romans even worshiped the emperor as a god. In this chapter, you'll see how this dramatic change occurred. You'll trace the gradual expansion of Roman power. You'll also explore the costs of this expansion, both for Romans and for the people they conquered. From Republic to Empire 323 34.2 From Republic to Empire: An Overview The growth of* Rome from a republic to an empire took place over 500 years. -

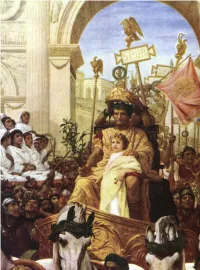

The Imperial Cult During the Reign of Domitian

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Filosofická fakulta Katedra archeologie a muzeologie Klasická archeologie Bc. Barbora Chabrečková Cisársky kult v období vlády Domitiána Magisterská diplomová práca Vedúca práce: Mgr. Dagmar Vachůtová, Ph.D. Brno 2017 MASARYK UNIVERSITY Faculty of Arts Department of Archaeology and Museology Classical Archaeology Bc. Barbora Chabrečková The Imperial Cult During the Reign of Domitian Master's Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Dagmar Vachůtová, Ph.D. Brno 2017 2 I hereby declare that this thesis is my own work, created with use of primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. ……………………………… Bc. Barbora Chabrečková In Brno, June 2017 3 Acknowledgement I would like to thank to my supervisor, Mgr. Dagmar Vachůtová, Ph.D., for her guidance and encouragement that she granted me throughout the entire creative process of this thesis, to my consulting advisor, Mgr. Ing. Monika Koróniová, who showed me the possibilities this topic has to offer, and to my friends and parents, for their care and support. 4 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 7 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. 8 I) Definition, Origin, and Pre-Imperial History of the Imperial Cult ................................... 10 1.) Origin in the Private Cult & the Term Genius ........................................................... 10 -

Page Proof Instructions and Queries

Page Proof Instructions and Queries Journal Title: CAE Article Number: 775904 Thank you for choosing to publish with us. This is your final opportunity to ensure your article will be accurate at publication. Please review your proof carefully and respond to the queries using the circled tools in the image below, which are available by clicking “Comment” from the right-side menu in Adobe Reader DC.* Please use only the tools circled in the image, as edits via other tools/methods can be lost during file conversion. For comments, questions, or formatting requests, please use . Please do not use comment bubbles/sticky notes . *If you do not see these tools, please ensure you have opened this file with Adobe Reader DC, available for free at https://get.adobe.com/reader or by going to Help > Check for Updates within other versions of Reader. For more detailed instructions, please see https://us.sagepub.com/ReaderXProofs. No. Query Please confirm that all author information, including names, affiliations, sequence, and contact details, is correct. Please review the entire document for typographical errors, mathematical errors, and any other necessary corrections; check headings, tables, and figures. Please confirm that the Funding and Conflict of Interest statements are accurate. Please note that this proof represents your final opportunity to review your article prior to publication, so please do send all of your changes now. AQ: 1 Please approve the edits to the article title. AQ: 2 Please check and suggest whether ‘70s and ‘80s mentioned in the article can be changed as 1970s and 1980s, respectively. -

Rome's Northern European Boundaries by Peter S. Wells

the limes hadrian’sand wall Rome’s Northern European Boundaries by peter s. wells Hadrian’s Wall at Housesteads, looking east. Here the wall forms the northern edge of the Roman fort (the grass to the right is within the fort’s interior). In the background the wall extends northeastward, away from the fort. s l l e W . S r e t e P 18 volume 47, number 1 expedition very wall demands attention and raises questions. Who built it and why? The Limes in southern Germany and Hadrian’s Wall in northern Britain are the most distinctive physical remains of the northern expansion and defense of the Roman Empire. Particularly striking are the size of these monuments today and their uninterrupted courses Ethrough the countryside. The Limes, the largest archaeological monument in Europe, extends 550 km (342 miles) across southern Germany, connecting the Roman frontiers on the middle Rhine and upper Danube Rivers. It runs through farmland, forests, villages, and towns, and up onto the heights of the Taunus and Wetterau hills. Hadrian’s Wall is 117 km (73 miles) long, crossing the northern part of England from the Irish Sea to the North Sea. While portions of Hadrian’s Wall run through urban Newcastle and Carlisle, its central courses traverse open landscapes removed from modern settlements. The frontiers of the Roman Empire in northwestern Europe in the period AD 120–250. For a brief period around AD 138–160, Roman forces in Britain established and maintained a boundary far- ther north, the Antonine Wall. The frontier zones, indicated here by oblique hatching, are regions in which intensive interaction took place between the Roman provinces and other European peoples.