The Comrade from Milan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rifondazione Comunista Dallo Scioglimento Del PCI Al “Movimento Dei Movimenti”

C. I. P. E. C., Centro di iniziativa politica e culturale, Cuneo L’azione politica e sociale senza cultura è cieca. La cultura senza l’azione politica e sociale è vuota. (Franco Fortini) Sergio Dalmasso RIFONDARE E’ DIFFICILE Rifondazione comunista dallo scioglimento del PCI al “movimento dei movimenti” Quaderno n. 30. Alla memoria di Ludovico Geymonat, Lucio Libertini, Sergio Garavini e dei/delle tanti/e altri/e che, “liberamente comunisti/e”, hanno costruito, fatto crescere, amato, odiato...questo partito e gli hanno dato parte della loro vita e delle loro speranze. Introduzione Rifondazione comunista nasce nel febbraio del 1991 (non adesione al PDS da parte di alcuni dirigenti e di tanti iscritti al PCI) o nel dicembre dello stesso anno (fondazione ufficiale del partito). Ha quindi, in ogni caso, compiuto i suoi primi dieci anni. Sono stati anni difficili, caratterizzati da scadenze continue, da mutamenti profondi del quadro politico- istituzionale, del contesto economico, degli scenari internazionali, sempre più tesi alla guerra e sempre più segnati dall’esistenza di una sola grande potenza militare. Le ottimistiche previsioni su cui era nato il PDS (a livello internazionale, fine dello scontro bipolare con conseguente distensione e risoluzione di gravi problemi sociali ed ambientali, a livello nazionale, crescita della sinistra riformista e alternanza di governo con le forze moderate e democratiche) si sono rivelate errate, così come la successiva lettura apologetica dei processi di modernizzazione che avrebbero dovuto portare ad un “paese normale”. Il processo di ricostruzione di una forza comunista non è, però, stato lineare né sarebbe stato possibile lo fosse. Sul Movimento e poi sul Partito della Rifondazione comunista hanno pesato, sin dai primi giorni, il venir meno di ogni riferimento internazionale (l’elaborazione del lutto per il crollo dell’est non poteva certo essere breve), la messa in discussione dei tradizionali strumenti di organizzazione (partiti e sindacati) del movimento operaio, la frammentazione e scomposizione della classe operaia. -

Note Alla Fine Del Secolo

Note alla fine del secolo - Aldo Garzia, 20.06.2017 Saggi. Tra pubblico e privato. «Diari 1988-1994» di Bruno Trentin per le Edizioni Ediesse Non dev’essere stato facile per Marcelle Marie Padovani, storica corrispondente del Nouvel Observateur, decidere di dare via libera alla pubblicazione dei diari di suo marito Bruno Trentin (Pavie 1926-Roma 2007). La scrittura diaristica è infatti per definizione intimista, una sorta di dialogo solitario con se stessi quasi psicanalitico. In più, può svelare tratti dell’autore che stridono con il suo personaggio pubblico, nel caso di Trentin una figura di assoluto prestigio del sindacalismo e della politica europei: giovanissimo partigiano, deputato comunista già nel 1963, poi segretario della Fiom, poi ancora segretario negli anni cruciali 1988-1994 della Cgil e infine per una legislatura parlamentare europeo. Il nome di Trentin è dunque stato legato per decenni alle vicende della Cgil, dove lo aveva chiamato Vittorio Foa all’Ufficio studi nel 1950, animandone l’azione e l’elaborazione. Proprio la forma diaristica dei testi contenuti in Diari 1988-1994 (a cura di Iginio Ariemma, pp. 510, euro 22, edizioni Ediesse) può farli apparire crudi nella forma e nei giudizi che contengono su protagonisti e passaggi della storia della sinistra. Valutazioni lapidarie e più o meno critiche sono riservate a tanti protagonisti di quegli anni, tra cui Pierre Carniti, Luciano Lama, Pietro Ingrao, Rossana Rossanda, Achille Occhetto, Massimo D’Alema, Fausto Bertinotti (a dividerlo verso quest’ultimo ci sono oltre ai rilevanti dissensi politici e di pratica sindacale le diversità di temperamento e di comportamento che lo irritano particolarmente). -

Italian Fascism Between Ideology and Spectacle

Fast Capitalism ISSN 1930-014X Volume 1 • Issue 2 • 2005 doi:10.32855/fcapital.200502.014 Italian Fascism between Ideology and Spectacle Federico Caprotti In April 1945, a disturbing scene was played out at a petrol station in Piazzale Loreto, in central Milan. Mussolini’s body was displayed for all to see, hanging upside down, together with those of other fascists and of Claretta Petacci, his mistress. Directly, the scene showed the triumph of the partisans, whose efforts against the Nazis had greatly accelerated the liberation of the North of Italy. The Piazzale Loreto scene was both a victory sign and a reprisal. Nazis and fascists had executed various partisans and displayed their bodies in the same place earlier in the war. Indirectly, the scene was a symbolic reversal of what had until then been branded as historical certainty. Piazzale Loreto was a public urban spectacle aimed at showing the Italian people that fascism had ended. The Duce was now displayed as a gruesome symbol of defeat in the city where fascism had first developed. More than two decades of fascism were symbolically overcome through a barbaric catharsis. The concept of spectacle has been applied to Italian fascism (Falasca-Zamponi 2000) in an attempt to conceptualize and understand the relationship between fascist ideology and its external manifestations in the public, symbolic, aesthetic, and urban spheres. This paper aims to further develop the concept of fascism as a society of spectacle by elaborating a geographical understanding of Italian fascism as a material phenomenon within modernity. Fascism is understood as an ideological construct (on which the political movement was based) which was expressed in the symbolic and aesthetic realm; its symbolism and art however are seen as having been rooted in material, historical specificity. -

The Surreal Voice in Milan's Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center 2-2021 The Surreal Voice in Milan's Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi Jason Collins The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4143 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE SURREALIST VOICE IN MILAN’S ITINERANT POETICS: DELIO TESSA TO FRANCO LOI by JASON M. COLLINS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2021 i © 2021 JASON M. COLLINS All Rights Reserved ii The Surreal Voice in Milan’s Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi by Jason M. Collins This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy _________________ ____________Paolo Fasoli___________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _________________ ____________Giancarlo Lombardi_____ Date Executive Officer Supervisory Committee Paolo Fasoli André Aciman Hermann Haller THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Surreal Voice in Milan’s Itinerant Poetics: Delio Tessa to Franco Loi by Jason M. Collins Advisor: Paolo Fasoli Over the course of Italy’s linguistic history, dialect literature has evolved a s a genre unto itself. -

Investigating Italy's Past Through Historical Crime Fiction, Films, and Tv

INVESTIGATING ITALY’S PAST THROUGH HISTORICAL CRIME FICTION, FILMS, AND TV SERIES Murder in the Age of Chaos B P ITALIAN AND ITALIAN AMERICAN STUDIES AND ITALIAN ITALIAN Italian and Italian American Studies Series Editor Stanislao G. Pugliese Hofstra University Hempstead , New York, USA Aims of the Series This series brings the latest scholarship in Italian and Italian American history, literature, cinema, and cultural studies to a large audience of spe- cialists, general readers, and students. Featuring works on modern Italy (Renaissance to the present) and Italian American culture and society by established scholars as well as new voices, it has been a longstanding force in shaping the evolving fi elds of Italian and Italian American Studies by re-emphasizing their connection to one another. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14835 Barbara Pezzotti Investigating Italy’s Past through Historical Crime Fiction, Films, and TV Series Murder in the Age of Chaos Barbara Pezzotti Victoria University of Wellington New Zealand Italian and Italian American Studies ISBN 978-1-137-60310-4 ISBN 978-1-349-94908-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-349-94908-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016948747 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

Reinventing Cities”

Milano Triennale, 25 Gennaio 2020 1 Struttura di “Reinventing Cities” Manifestazione 2 fasi Proposta d’interesse Regolamento Site Specific 2 tipologie di comune a tutte le Città Requirements-SSR partecipanti, a tutti i siti, ai requisiti specifici alle documenti team proponenti e alle quali devono attenersi i proposte team partecipanti e i progetti 2 Presentazione delle proposte devono essere conformi alle devono essere conformi agli specifiche e ai requisiti obiettivi, criteri e requisiti descritti in ciascun comuni elencati nel documento dei Requisiti Regolamento Specifici del Sito (SSR) i progetti devono affrontare le 10 sfide per il clima 1. Efficienza energetica ed energia a basse emissioni 2. Valutazione del ciclo di vita e gestione sostenibile dei materiali da costruzione 3. Mobilità a bassa emissione 4. Resilienza e adattamento climatico 5. Servizi ecologici per il territorio e lavori green 6. Gestione sostenibile delle risorse idriche 7. Gestione sostenibile dei rifiuti 8. Biodiversità, riforestazione urbana e agricoltura 9. Azioni inclusive, benefici sociali e impegno della comunità 10. Architettura e design urbano innovativo 3 Presentazione delle proposte architetti, esperti in campo ambientale, sviluppatori, investitori e appaltatori, titolari di progetti creativi, start-up, artisti, membri della comunità locale, stakeholders, etc. i team almeno una persona qualificata deve essere nominata come responsabile del progetto (ad esempio un architetto o un urbanista) e un esperto in campo ambientale si deve identificare un capogruppo -

Il Manifesto E Il PCI, in “Il Calendario Del Popolo”, Numero 587, Maggio 1995

Il Manifesto e il PCI, in “Il calendario del popolo”, numero 587, maggio 1995 “Il manifesto” e il PCI di Sergio Dalmasso Dai primi anni Sessanta, il PCI si trova davanti a problemi che lo obbligano a riconsiderare, almeno in parte, la propria strategia: l’affermarsi, anche se con ritardi e contraddizioni, di una società capitalistica avanzata e il parallelo sviluppo di un forte ciclo del movimento di classe con inediti protagonisti e modi di essere. Sino ad allora ha retto la gestione di Togliatti che ha costruito un partito unico ed originale all’interno del movimento comunista internazionale. Pur con accentuazioni e svolte (socialfascismo, fronti popolari, svolta di Salerno ed unità nazionale, policentrismo e via nazionale), Togliatti riesce negli anni Quaranta e Cinquanta a legare generazioni ed esperienze politiche diverse, formazioni culturali anche divergenti (dal materialismo dialettico alla cultura liberaldemocratica, dal terzinternazionalismo al crocianesimo). Caratterizzano il “togliattismo” un forte legame con l’URSS da cui pure, dopo il ‘56, la via nazionale si stacca nella proposta di diversi percorsi per giungere al socialismo, e la lettura della Costituzione (da qui le forti polemiche negli anni Sessanta con il Partito comunista cinese) come capace di operare trasformazioni profonde e radicali che introducano “elementi di socialismo” anche all’interno di una società capitalistica, una duttilità che produce una esperienza di massa unica in Europa, un patrimonio di lotte, di impegno, di sofferenze che fanno del PCI un corpo interno alla società italiana, fiero della sua specificità e diversità1. Legittimano questa realtà i successi, le vittorie elettorali, la forte crescita organizzativa non solo del partito, ma anche di tutti gli organismi collaterali, dal sindacato all’UDI, dalle cooperative all’ARCI. -

Aldo Natoli, Comunista Senza Partito

Aldo Natoli, comunista senza partito - Aldo Garzia, 28.09.2019 SCAFFALE. Un volume a cura di Ella Baffoni e Peter Kammerer per le edizioni dell’Asino ne ricostruisce il pensiero Aldo Natoli (Messina 1913-Roma 2010), tra i fondatori del Manifesto, radiato dal Comitato centrale del Pci nel 1969 con Rossana Rossanda e Luigi Pintor (altri dirigenti e militanti subiranno la stessa sorte, tra cui i fondatori di questo giornale), era personaggio schivo e autorevole. Per lui parlavano i tre anni trascorsi in carcere a Civitavecchia con Vittorio Foa e Carlo Ginzburg in piena dittatura fascista, l’elezione alla Camera fin dalla prima legislatura nel 1948, gli anni della clandestinità, il lungo periodo in cui è stato segretario della Federazione romana del Pci (dal 1946 al 1954, mitiche le sue battaglie urbanistiche in Campidoglio). INSIEME A ELISEO MILANI (ex segretario della Federazione di Bergamo, pure lui deputato al momento della radiazione), era tra i pochi del gruppo storico del Manifesto ad avere una esperienza di direzione del partito «sul campo e dal vivo». Quel tratto peculiare non l’avevano Luigi Pintor, Luciana Castellina, Valentino Parlato (impegnati prevalentemente nella stampa di partito), né Rossana Rossanda (ha diretto la Sezione culturale nazionale) e né Lucio Magri funzionario a Botteghe oscure presso la Sezione lavoro di massa. Saranno poi proprio Rossanda e Magri a dirigere il manifesto mensile nel 1969. Contro la radiazione si schierarono Cesare Luporini, Lucio Lombardo Radice e Fabio Mussi. Tre gli astenuti: Giuseppe Chiarante, Sergio Garavini e Nicola Badaloni. Ora a restituire la complessità del personaggio Natoli ci pensa il libro Aldo Natoli. -

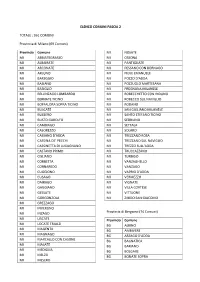

Elenco Comuni Fascia 2 Totale

ELENCO COMUNI FASCIA 2 TOTALE : 361 COMUNI Provincia di Milano (69 Comuni) Provincia Comune MI NOSATE MI ABBIATEGRASSO MI OSSONA MI ALBAIRATE MI PANTIGLIATE MI ARCONATE MI PESSANO CON BORNAGO MI ARLUNO MI PIEVE EMANUELE MI BAREGGIO MI POZZO D'ADDA MI BASIANO MI POZZUOLO MARTESANA MI BASIGLIO MI PREGNANA MILANESE MI BELLINZAGO LOMBARDO MI ROBECCHETTO CON INDUNO MI BERNATE TICINO MI ROBECCO SUL NAVIGLIO MI BOFFALORA SOPRA TICINO MI RODANO MI BUSCATE MI SAN GIULIANO MILANESE MI BUSSERO MI SANTO STEFANO TICINO MI BUSTO GAROLFO MI SEDRIANO MI CAMBIAGO MI SETTALA MI CASOREZZO MI SOLARO MI CASSANO D'ADDA MI TREZZANO ROSA MI CASSINA DE' PECCHI MI TREZZANO SUL NAVIGLIO MI CASSINETTA DI LUGAGNANO MI TREZZO SULL'ADDA MI CASTANO PRIMO MI TRUCCAZZANO MI CISLIANO MI TURBIGO MI CORBETTA MI VANZAGHELLO MI CORNAREDO MI VANZAGO MI CUGGIONO MI VAPRIO D'ADDA MI CUSAGO MI VERMEZZO MI DAIRAGO MI VIGNATE MI GAGGIANO MI VILLA CORTESE MI GESSATE MI VITTUONE MI GORGONZOLA MI ZIBIDO SAN GIACOMO MI GREZZAGO MI INVERUNO MI INZAGO Provincia di Bergamo (74 Comuni) MI LISCATE Provincia Comune MI LOCATE TRIULZI BG ALBINO MI MAGENTA BG AMBIVERE MI MAGNAGO BG ARZAGO D'ADDA MI MARCALLO CON CASONE BG BAGNATICA MI MASATE BG BARIANO MI MEDIGLIA BG BOLGARE MI MELZO BG BONATE SOPRA MI MESERO BG BONATE SOTTO BG PALAZZAGO BG BOTTANUCO BG PALOSCO BG BREMBATE DI SOPRA BG POGNANO BG BRIGNANO GERA D'ADDA BG PONTIDA BG CALCINATE BG PRADALUNGA BG CALCIO BG PRESEZZO BG CALUSCO D'ADDA BG ROMANO DI LOMBARDIA BG CALVENZANO BG SOLZA BG CAPRIATE SAN GERVASO BG SORISOLE BG CAPRINO BERGAMASCO -

Intergenerational Dialogues in Milan Peripheries a Research by Design Applied to Via Padova

UIA 2021 RIO: 27th World Congress of Architects Intergenerational dialogues in Milan peripheries A research by design applied to via Padova Pierre-Alain Croset Politecnico di Milano, DAStU Elena Fontanella Politecnico di Milano, DAStU Abstract from an anthropological, sociological and After more than twenty years of political reflection on the theme of contraction, Milan population has returned intergenerational dialogue in relation to the to growth since 2015, reaching in 2019 the redevelopment of urban peripheral areas. levels of 1991, increasing especially in the age group between 30 and 50 years. At the same time, we are facing the decreasing of new-born residents and the progressive This article presents some critical considerations aging of the population, which especially in developed at the end of a Politecnico di Milano 1 the peripheral areas can lead to urban design studio carried out between phenomena of social exclusion and February and July 2019, as part of the teaching experimentation platform “Ri-formare Periferie marginalization. This can be counteracted 2 through the activation of intergenerational Milano Metropolitana” (Re-forming Milan peripheries) started to promote research by education and solidarity actions. The design on the regeneration of peripheral areas. project explorations applied to the area of As architects, we consider the design activity as via Padova focus on this possibility, a form of applied research3, to be tested with the assuming intergenerational dialogue as a students based on precise research questions. tool for social and spatial requalification. The brief of the design studio was developed There are numerous examples in Europe of based on our interest in the relationships positive experiences based on solidarity between social issues, linked to the aging of the and collaboration between young people population (particularly in Italy), and new forms and elderly. -

Distretto Ambito Distrettuale Comuni Abitanti Ovest Milanese Legnano E

Ambito Distretto Comuni abitanti distrettuale Busto Garolfo, Canegrate, Cerro Maggiore, Dairago, Legnano, Nerviano, Legnano e Parabiago, Rescaldina, S. Giorgio su Legnano, S. Vittore Olona, Villa 22 254.678 Castano Primo Cortese ; Arconate, Bernate Ticino, Buscate, Castano Primo, Cuggiono, Inveruno, Magnano, Nosate, Robecchetto con Induno, Turbigo, Vanzaghello Ovest Milanese Arluno, Bareggio, Boffalora sopra Ticino, Casorezzo, Corbetta, Magenta, Magenta e Marcallo con Casone, Mesero, Ossona, Robecco sul Naviglio, S. Stefano 28 211.508 Abbiategrasso Ticino, Sedriano, Vittuone; Abbiategrasso, Albairate, Besate, Bubbiano, Calvignasco, Cisliano, Cassinetta di Lugagnano, Gaggiano, Gudo Visconti, Morimomdo, Motta Visconti, Ozzero, Rosate, Vermezzo, Zelo Surrigone Garbagnate Baranzate, Bollate, Cesate, Garbagnate Mil.se, Novate Mil.se, Paderno 17 362.175 Milanese e Rho Dugnano, Senago, Solaro ; Arese, Cornaredo, Lainate, Pero, Pogliano Rhodense Mil.se, Pregnana Mil.se, Rho, Settimo Mil.se, Vanzago Assago, Buccinasco, Cesano Boscone, Corsico, Cusago, Trezzano sul Corsico 6 118.073 Naviglio Sesto San Giovanni, Cologno Monzese, Cinisello Balsamo, Bresso, Nord Milano Nord Milano 6 260.042 Cormano e Cusano Milanino Milano città Milano Milano 1 1.368.545 Bellinzago, Bussero, Cambiago, Carugate, Cassina de Pecchi, Cernusco sul Naviglio, Gessate, Gorgonzola, Pessano con Bornago, Basiano, Adda Grezzago, Masate, Pozzo d’Adda, Trezzano Rosa, Trezzo sull’Adda, 28 338.123 Martesana Vaprio d’Adda, Cassano D’Adda, Inzago, Liscate, Melzo, Pozzuolo Martesana, -

PRODUZIONE PRO-CAPITE - Anno 2019 - DM 26 MAGGIO 2016

PRODUZIONE PRO-CAPITE - Anno 2019 - DM 26 MAGGIO 2016 - Rescaldina Solaro Trezzo sull'Adda Cesate Legnano Grezzago Cerro Maggiore Trezzano Rosa Vanzaghello San Vittore Olona Basiano Magnago Vaprio d'Adda San Giorgio su Legnano Garbagnate MilaneseSenago Paderno Dugnano Cambiago Pozzo d'Adda Dairago Villa Cortese Canegrate Lainate Masate Cinisello Balsamo Nosate Gessate Nerviano Cusano Milanino Castano Primo Parabiago Arese Bollate Carugate Pessano con Bornago Buscate Busto Garolfo Inzago Arconate Cormano Pogliano Milanese Bresso Bussero Sesto San GiovanniCologno Monzese Bellinzago Lombardo Rho Novate Milanese Cernusco sul Naviglio Gorgonzola Turbigo Casorezzo Baranzate Cassano d'Adda Inveruno Robecchetto con Induno Vanzago Cassina de' Pecchi Pregnana Milanese Vimodrone Pozzuolo Martesana Pero Arluno Cuggiono Ossona Cornaredo Vignate Melzo Mesero Pioltello Santo Stefano Ticino Sedriano Marcallo con Casone Segrate Settimo Milanese Truccazzano Bernate Ticino Vittuone Bareggio Rodano Liscate Milano Boffalora sopra Ticino Corbetta Magenta Settala Cusago Cesano Boscone Peschiera Borromeo Pantigliate Cisliano Corsico Cassinetta di Lugagnano Albairate Robecco sul Naviglio Trezzano sul Naviglio Buccinasco Paullo San Donato Milanese Mediglia Tribiano Gaggiano Assago Abbiategrasso Vermezzo con Zelo Rozzano San Giuliano Milanese Colturano Opera Gudo Visconti Dresano Ozzero Noviglio Locate di Triulzi Zibido San Giacomo Vizzolo Predabissi Pieve Emanuele Melegnano Rosate Basiglio Morimondo Carpiano Binasco Cerro al Lambro BubbianoCalvignasco San Zenone