Mining Agreements in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY and CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), The Australian National University, Acton, ACT, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE UNCLE ROY PATTERSON AND JENNIFER JONES Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464066 ISBN (online): 9781760464073 WorldCat (print): 1224453432 WorldCat (online): 1224452874 DOI: 10.22459/OTL.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: Patterson family photograph, circa 1904 This edition © 2020 ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. Contents Acknowledgements ....................................... vii Note on terminology ......................................ix Preface .................................................xi Introduction: Meeting and working with Uncle Roy ..............1 Part 1: Sharing Taungurung history 1. -

Stewcockatoo Internals 19.Indd 1 17/6/10 7:09:24 PM

StewCockatoo_Internals_19.indd 1 17/6/10 7:09:24 PM StewCockatoo_Internals_19.indd 2-3 17/6/10 7:09:24 PM W r i t t e n b y R u t h i e M a y I l l u s t r a t e d b y L e i g h H O B B S Stew a Cockatoo My Aussie Cookbook StewCockatoo_Internals_19.indd 4-5 17/6/10 7:09:30 PM Table of Contents 4 Cooee, G’Day, Howya Goin’? 22 The Great Aussie Icon We Australians love our slang. ‘Arvo : Dinky-di Meat Pie tea’ sounds friendlier than ‘afternoon 5 Useful Cook’s Tools tea’ and ‘fair dinkum’ is more fun 24 Grandpa Bruce’s Great Aussie BBQ to say than ‘genuine’. This book is 6 ’Ave a Drink,Ya Mug! 26 It’s a Rissole, Love! jam-packed with Aussie slang. If you 8 The Bread Spread come across something you haven’t 28 Bangers, Snags and Mystery Bags heard before, don’t worry, now is your 10 Morning Tea for Lords chance to pick up some you-beaut lingo and Bush Pigs 30 Fish ’n’ Chips Down Under you can use with your mates. 12 Bikkies for the Boys 32 Bush Tucker 14 Arvo Tea at Auntie Beryl’s 34 From Over Yonder to Down Under 16 From the Esky 36 Dessert Dames For Norm Corker - the best sav stew maker 18 Horse Doovers 38 All Over, Pavlova in all of Oz. On ya, Gramps!-RM 20 Whacko the Chook! 40 Index Little Hare Books an imprint of Hardie Grant Egmont 85 High Street Cooee, g’day, Prahran, Victoria 3181, Australia www.littleharebooks.com howya goin’? Copyright © text Little Hare Books 2010 Copyright © illustrations Leigh Hobbs 2010 Text by Ruthie May First published 2010 All rights reserved. -

September Shire of Roebourne Local Planning Strategy Evidential Analysis Paper: (Major Industry Projects)

September Shire of Roebourne Local Planning Strategy Evidential Analysis Paper: (Major Industry Projects) Shire of Roebourne – Economic Development Strategy Preliminary Paper Version Control Document History and Status Status Issued To Qty Date Reviewed Approved Draft MP 1 23/4/13 Report Details Name: Author: Client: Name of doc: Doc version: Project number: P85029 SM Shire of Shire of Roebourne Electronic Draft 85029 MPD Roebourne – Local Planning P1263 SM Strategy 3103 PS Disclaimer: If you are a party other than the Shire of Roebourne, MacroPlan Dimasi: owes you no duty (whether in contract or in tort or under statute or otherwise) with respect to or in connection with the attached report or any part thereof; and will have no liability to you for any loss or damage suffered or costs incurred by you or any other person arising out of or in connection with the provision to you of the attached report or any part thereof, however the loss or damage is caused, including, but not limited to, as a result of negligence. If you are a party other than the Shire of Roebourne and you choose to rely upon the attached report or any part thereof, you do so entirely at your own risk. The responsibility for determining the adequacy or otherwise of our terms of reference is that of the Shire of Roebourne. The findings and recommendations in this report are given in good faith but, in the preparation of this report, we have relied upon and assumed, without independent verification, the accuracy, reliability and completeness of the information made available to us in the course of our work, and have not sought to establish the reliability of the information by reference to other evidence. -

German Lutheran Missionaries and the Linguistic Description of Central Australian Languages 1890-1910

German Lutheran Missionaries and the linguistic description of Central Australian languages 1890-1910 David Campbell Moore B.A. (Hons.), M.A. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Social Sciences Linguistics 2019 ii Thesis Declaration I, David Campbell Moore, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text and, where relevant, in the Authorship Declaration that follows. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis contains published work and/or work prepared for publication, some of which has been co-authored. Signature: 15th March 2019 iii Abstract This thesis establishes a basis for the scholarly interpretation and evaluation of early missionary descriptions of Aranda language by relating it to the missionaries’ training, to their goals, and to the theoretical and broader intellectual context of contemporary Germany and Australia. -

Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254)

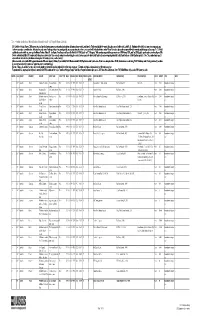

Table1.—Attribute data for the map "Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254). [The United States Geological Survey (USGS) surveys international mineral industries to generate statistics on the global production, distribution, and resources of industrial minerals. This directory highlights the economically significant mineral facilities of Asia and the Pacific. Distribution of these facilities is shown on the accompanying map. Each record represents one commodity and one facility type for a single location. Facility types include mines, oil and gas fields, and processing plants such as refineries, smelters, and mills. Facility identification numbers (“Position”) are ordered alphabetically by country, followed by commodity, and then by capacity (descending). The “Year” field establishes the year for which the data were reported in Minerals Yearbook, Volume III – Area Reports: Mineral Industries of Asia and the Pacific. In the “DMS Latitiude” and “DMS Longitude” fields, coordinates are provided in degree-minute-second (DMS) format; “DD Latitude” and “DD Longitude” provide coordinates in decimal degrees (DD). Data were converted from DMS to DD. Coordinates reflect the most precise data available. Where necessary, coordinates are estimated using the nearest city or other administrative district.“Status” indicates the most recent operating status of the facility. Closed facilities are excluded from this report. In the “Notes” field, combined annual capacity represents the total of more facilities, plus additional -

Borrowing, Sound Change and Reduplication in Iwaidja

Doubled up all over again: borrowing, sound change and reduplication in Iwaidja Nicholas Evans Department of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies Australian National University [email protected] Abstract This article examines the interactions between reduplication, sound change, and borrowing, as played out in the Iwaidja language of Cobourg Peninsula, Arnhem Land, in Northern Australia, a non-Pama-Nyungan language of the Iwaidjan family. While Iwaidja traditionally makes use of (various types of) right-reduplication, contact with two other left-reduplicating languages – one Australian (Bininj Gun-wok) and one Austronesian (Makassarese) – has led to the introduction of several (non-productive) left-reduplicating patterns. At the same time as these new patterns have been entering the language, the cumulative effect of sweeping sound changes within Iwaidja has complicated the transparency of reduplicative outputs. This has left the language with an extremely varied and complicated set of reduplication types, for some of which the analysis is no longer synchronically recoverable by children. Keywords: Australian languages, Iwaidja, language contact, directionality, Makassarese, reanalysis 1. Introduction Despite growing interest in language contact on the one hand, and reduplication on the other, there has been little research to date on how diachrony and language contact impact upon reduplicative patterns. 1 In this article I examine precisely this theme, as played out in the Iwaidja language of Cobourg Peninsula, Arnhem Land, in Northern Australia, a non-Pama-Nyungan language of the Iwaidjan family spoken by around 150 people now mostly living on and around Croker Island in the Northern Territory (see Evans 2000 for a survey of this family). -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UM l films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UME a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy, ffigher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UM l directly to order. UMl A Bell & Howell Infoimation Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Velar-Initial Etyma and Issues in Comparative Pama-Nyungan by Susan Ann Fitzgerald B.A.. University of V ictoria. 1989 VI.A. -

Roy Hill Celebrates Historic First Shipment

10 December 2015 Roy Hill Celebrates Historic First Shipment Hancock Prospecting Pty Ltd and Roy Hill Holdings Pty Ltd are pleased to announce the historic inaugural shipment from Port Hedland of low phosphorous iron ore from the Roy Hill mine on the MV ANANGEL EXPLORER bound for POSCO’s steel mills in South Korea. Mrs Gina Rinehart, Chairman of Hancock and Roy Hill Holdings Pty Ltd, said “The Roy Hill mega project is the culmination of hard-work from the dedicated small executive and technical teams at Hancock and more recently by the entire Roy Hill team.” “Given that the mega Roy Hill Project was a largely greenfield project that carried with it significant risks and considerable cost, it is remarkable that a relatively small company such as Hancock Prospecting has been able to take on and complete a project of this sheer size and complexity.” “The Roy Hill Project has recorded many achievements already and with the first shipment it will also hold one of the fastest construction start-ups of any major greenfield resource project in Australia. This is a considerable achievement, and although the media refer to a contractors date for shipment, it remains that the shipment still occurred ahead of what the partners schedule had planned in the detailed bankable feasibility study.” “The performance on the construction gives great confidence we can achieve performance as a player of international significance in the iron ore industry. To put the scale of the Roy Hill iron ore project into perspective in regard to Australia’s economy, when the mine is operating at its full capacity, Roy Hill will generate export revenue significantly greater than either Australia's lamb and mutton export industry or our annual wine exports. -

APPENDIX G Language Codes Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data Collection (QHAPDC) 2019-2020 V0.1

APPENDIX G Language Codes Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data Collection (QHAPDC) 2019-2020 V0.1 Appendix G Published by the State of Queensland (Queensland Health), 2019 This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au © State of Queensland (Queensland Health) 2019 You are free to copy, communicate and adapt the work, as long as you attribute the State of Queensland (Queensland Health). For more information contact: Statistical Services and Integration Unit, Statistical Services Branch, Department of Health, GPO Box 48, Brisbane QLD 4001, email [email protected]. An electronic version of this document is available at https://www.health.qld.gov.au/hsu/collections/qhapdc Disclaimer: The content presented in this publication is distributed by the Queensland Government as an information source only. The State of Queensland makes no statements, representations or warranties about the accuracy, completeness or reliability of any information contained in this publication. The State of Queensland disclaims all responsibility and all liability (including without limitation for liability in negligence) for all expenses, losses, damages and costs you might incur as a result of the information being inaccurate or incomplete in any way, and for any reason reliance was placed on such information. APPENDIX G – 2019-2020 v1.0 2 Contents Language Codes – Alphabetical Order ....................................................................................... 4 Language Codes – Numerical Order ......................................................................................... 31 APPENDIX G – 2019-2020 v1.0 3 Language Codes – Alphabetical Order From 1st July 2011 a new language classification was implemented in Queensland Health (QH). -

Bidder's Statement Hancock Prospecting Pty Ltd Riversdale Res E ' Limited

HANCOCK PROSPECTING PTY LTD Bidder's Statement containing a Cash Offer by Hancock Prospecting Pty Ltd ACN 008 676 417 through its wholly-owned subsidiary Hancock Corporation Pty Ltd ACN 615 809 7 40 to acquire all of your shares in D7€/0, Aycock_ Riversdale Res e ' Limited cog PO AT1) Fr] LSD ACN 152 669 291 27[/1] for $2.20 per share (which will increase to $2.50 per share if Hancock Corporation's voting power in Riversdale exceeds 50% prior to the end of the Offer Period) subject to the terms and conditions of the Offer. ACCEPT THIS CASH OFFER This is an important document and requires your attention. If you are in any doubt about how to deal with this document, you should contact your broker, financial adviser or legal adviser. Further Information If you have any queries in relation to the Offer, please contact the Offer information line on +618 9429 8222 between 12.00pm and 8.00pm (Sydney time) Monday to Friday. 3446-0556-6732v22 Contents 1 Important information 4 1.1 Key Dates 4 1.2 How to Accept the Offer 4 1.3 Important notice 4 1.4 Further Information 4 1.5 Defined terms 4 1.6 Investment decisions 5 1.7 Disclaimer as to forward looking statements 5 1.8 Notice to foreign Riversdale Shareholders 5 1.9 Information on Riversdale 5 1.10 Privacy 5 1.11 Internet 6 Director's Letter 7 2 Features of the Offer 10 3 Why Riversdale Shareholders should ACCEPT the Offer 12 3.1 Founding Shareholders' Statements of Intent support the Offer 12 3.2 The Offer Price represents a compelling premium to recent issue prices 12 3.3 The Offer provides shareholders -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

For Personal Use Only Use Personal For

BHP Billiton Limited ABN 49 004 028 077 180 Lonsdale Street Melbourne Victoria 3000 Australia 18 September 2012 Tel +61 1300 55 47 57 Fax +61 3 9609 3015 www.bhpbilliton.com To: Australian Securities Exchange 2012 US ANNUAL REPORT (Form 20-F) Please find attached a copy of BHP Billiton’s 2012 US Annual Report (Form 20-F), which has been filed with the United States Securities and Exchange Commission. This document has been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the United States Securities and Exchange Commission and, as such, does not comply with the reporting requirements under the Australasian Code for Reporting of Exploration Results, Mineral Resources and Ore Reserves. Jane McAloon Group Company Secretary For personal use only A member of the BHP Billiton Group which is headquartered in Australia Registered Office: Level 27 BHP Billiton Centre, 180 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia ABN 49 004 028 077 Registered in Australia UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ‘ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR 12(g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15 (d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2012 OR ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15 (d) OF THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 ‘ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report For the transition period from to Commission file number: 001-09526 Commission file number: 001-31714 BHP BILLITON LIMITED BHP BILLITON PLC (ABN 49 004 028 077) (REG.