Final Report 2006 Presidential and Local Council Elections Yemen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yemen in Crisis

A Conflict Overlooked: Yemen in Crisis Jamison Boley Kent Evans Sean Grassie Sara Romeih Conflict Risk Diagnostic 2017 Conflict Background Yemen has a weak, highly decentralized central government that has struggled to rule the northern Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) and the southern People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY).1 Since the unification of these entities in 1990, Yemen has experienced three civil conflicts. As the poorest country in the Arab world, Yemen faces serious food and water shortages for a population dispersed over mountainous terrain.2 The country’s weaknesses have been exploited by Saudi Arabia which shares a porous border with Yemen. Further, the instability of Yemen’s central government has created a power vacuum filled by foreign states and terrorist groups.3 The central government has never had effective control of all Yemeni territory. Ali Abdullah Saleh, who was president of Yemen for 34 years, secured his power through playing factions within the population off one another. The Yemeni conflict is not solely a result of a Sunni-Shia conflict, although sectarianism plays a role.4 The 2011 Arab Spring re-energized the Houthi movement, a Zaydi Shia movement, which led to the overthrow of the Saleh government. Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi took office as interim president in a transition led by a coalition of Arab Gulf states and backed by the United States. Hadi has struggled to deal with a variety of problems, including insurgency, the continuing loyalty of many military officers to former president Saleh, as well as corruption, unemployment and food insecurity.5 Conflict Risk Diagnostic Indicators Key: (+) Stabilizing factor; (-) Destabilizing factor; (±) Mixed factor Severe Risk - Government military expenditures have been generally stable between 2002-2015, at an average of 4.8% of GDP. -

Anglais (English

YEMEN Al Hudaydah Displacement/Response Update 03 – 09 August Al Hudaydah Aden Ibb/Taizz Sana’a Hub Hub Hub Hub Displacement Response Displacement Response Displacement Response Displacement Response 22,964 HHs 13,129 HHs 3,068 HHs 1,695 HHs 4,713 HHs 1,140 HHs 25,396 HHs 749 HHs Key Figures Overview In Al Hudaydah hub, strikes near AlThawra hospital, a fish market, and the radio building in Al Hudaydah City result in several deaths and injuries. These a�acks against civilian persons and objects are a viola�on of IHL (Interna�onal Humanitarian Law) and may cons�tute a war crime. In Sana’a hub, authori�es agreed to allow a discreet cash for rent scheme for 278 families from Al Hudaydah who have recently been hosted in 9 schools in Amanat Al Asimah. SNC (Sub-Na�onal Cluster) organized a mee�ng with the Partners working in the Transit and IDP hos�ng sites (schools) to discuss sequences for the implementa�on of the agreed scheme to ensure capturing the needs of sites residents through mul�-sectoral needs assessment, payment of cash for rent, restora�on of schools and iden�fica- �on of new site for con�nued registra�on of new IDPs from Al Hudaydah. ADRA reported that there are 36 IDP families who are residing in Mahw Al Omiah school and Al Hamzah school in Dhamar governorate In Aden hub, the security situa�on in Aden governorate worsened further this week with two IEDs (Improvised Explosive Devices) explosions in Enma’a city and Al Mualla district also the city experienced security unrest including blocked roads due to public protest and security deployments that spread in various loca�ons. -

Security Council Distr.: General 27 January 2020

United Nations S/2020/70 Security Council Distr.: General 27 January 2020 Original: English Letter dated 27 January 2020 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council The members of the Panel of Experts on Yemen have the honour to transmit herewith the final report of the Panel, prepared in accordance with paragraph 6 of resolution 2456 (2019). The report was provided to the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 2140 (2014) on 27 December 2019 and was considered by the Committee on 10 January 2020. We would appreciate it if the present letter and the report were brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Dakshinie Ruwanthika Gunaratne Coordinator Panel of Experts on Yemen (Signed) Ahmed Himmiche Expert (Signed) Henry Thompson Expert (Signed) Marie-Louise Tougas Expert (Signed) Wolf-Christian Paes Expert 19-22391 (E) 070220 *1922391* S/2020/70 Final report of the Panel of Experts on Yemen Summary After more than five years of conflict, the humanitarian crisis in Yemen continues. The country’s many conflicts are interconnected and can no longer be separated by clear divisions between external and internal actors and events. Throughout 2019, the Houthis and the Government of Yemen made little headway towards either a political settlement or a conclusive military victory. In a continuation from 2018, the belligerents continued to practice economic warfare: using economic obstruction and financial tools as weapons to starve opponents of funds or materials. Profiteering from the conflict is endemic. -

The War in Yemen: 2011-2018: the Elusive Road to Peace

Working Paper 18-1 By Sonal Marwah and Tom Clark The War in Yemen: 2011-2018 The elusive road to peace November 2018 The War in Yemen: 2011-2018 The elusive road to peace By Sonal Marwah and Tom Clark Working Paper 18-1 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publications Data The War in Yemen: 2011-2018: The elusive road to peace ISBN 978-1-927802-24-3 © 2018 Project Ploughshares First published November 2018 Please direct enquires to: Project Ploughshares 140 Westmount Road North Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G6 Canada Telephone: 519-888-6541 Email: [email protected] Editing: Wendy Stocker Design and layout: Tasneem Jamal Table of Contents Glossary of Terms i List of Figures ii Acronyms and Abbreviations iii Acknowledgements v Executive Summary 1 Introduction 2 Background 4 Participants in the Conflict 6 Major local actors 6 Foreign and regional actors 7 Major arms suppliers 7 Summary of the Conflict (2011-2018) 8 Civil strife breaks out (January 2011 to March 2015) 8 The internationalization of conflict (2015) 10 An influx of weapons and more human-rights abuses (2016) 10 A humanitarian catastrophe (2017- June 2018) 13 The Scale of the Forgotten War 16 Battle-related deaths 17 Forcibly displaced persons 17 Conflict and food insecurity 22 Infrastructural collapse 23 Arming Saudi Arabia 24 Prospects for Peace 26 Regulation of Arms Exports 30 The Path Ahead and the UN 32 Conclusion 33 Authors 34 Endnotes 35 Photo Credits 41 Glossary of Terms Arms Trade Treaty: A multilateral treaty, which entered into force in December 2014, that establishes -

Political Instability in Yemen (1962- 2014)

T.C. ANKARA YILDIRIM BEYAZIT UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE POLITICAL INSTABILITY IN YEMEN (1962- 2014) MASTER’S THESIS Sohaib Abdulhameed Abdulsalam SHAMSAN DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION ANKARA, 2020 T.C. ANKARA YILDIRIM BEYAZIT UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES POLITICAL INSTABILITY IN YEMEN (1962- 2014) MASTER’S THESIS Sohaib Abdulhameed Abdulsalam SHAMSAN DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION Prof. Dr. Yılmaz BINGÖL ANKARA 2020 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences __________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Seyfullah YILDIRIM Manager of Institute of Social Science I certify that this thesis satisfies the entire requirement as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science and Public Administration. ___________________________ Prof. Dr. Yılmaz Bingöl Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. ___________________________ Prof. Dr. Yılmaz Bingöl Supervisor Examining Committee Members: 1. Prof. Dr. Yılmaz BİNGÖL AYBU, PSPA ________________________ 2. Assist. Prof. Dr Güliz Dinç. AYBU, PSPA ________________________ 3. Prof. Dr. Murat ÖNDER ASBÜ ________________________ DECLARATION I hereby declare that all information in this document obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Sohaib Abdulhameed Abdulsalam SHAMSAN ___________________________ ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First, I wish to show my gratitude to, and express my sincere appreciation to my supervisor, Professor Dr. -

October 2020

HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN October 2020 *** All Health Cluster Coordination meetings are conducted virtually. YEMEN Emergency Level: Level 3 Reporting period: October 2020 7.3M 17.9M Targeted with Health 3.34 508M 1Million PIN of Health Assistance Interventions Million** IDPs Funds required Returnees HIGHLIGHTS HEALTH SECTOR A total of 1,958 Health Facilities (16 Governorate 71 HEALTH CLUSTER PARTNERS Hospitals, 131 District Hospitals, 62 General 9.7 M PEOPLE IN ACUTE NEED Hospitals, 21 Specialized Hospitals, 458 Health KITS DELIVERED TO HEALTH FACILITIES/PARTNERS Centers and 1,270 Health Units) are being 13 IEHK BASIC KITS supported by Health Cluster Partners. 13 IEHK SUPPLEMENTARY KITS 1 TRAUMA KITS As of the 24th of October 2020, 2064 positive 47 OTHER TYPES OF KITS COVID-19 cases and 601 deaths have been SUPPORTED HEALTH FACILITIES confirmed by MOH Aden (COVID-19 reports are only from the southern governorates). 1,958 HEALTH FACILITIES The cumulative total number of suspected Cholera 1,264,050 OUTPATIENT CONSULTATIONS cases from the 1st of January to the 31 of Oct, 11,615 SURGERIES 2020 is 208606 with 68 associated deaths (CFR ASSISTED DELIVERIES (NORMAL & 51,972 0.03%). Children under five represent 26% whilst C/S) the elderly above 60 years of age accounted for VACCINATION 6.0% of total suspected cases. The outbreak has so far affected in 2020 : 22 of 23 governorates and 94,025 PENTA 3 299 of 333 districts in Yemen. EDEWS As of 31st of October 2020, Health Cluster Partners 1,982 SENTINEL SITES supported a total number of 142 DTCs and 226 FUNDING US$ ORCs in 169 Priority districts. -

Yemen: Civil War and Regional Intervention

Yemen: Civil War and Regional Intervention Updated August 24, 2018 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R43960 Yemen: Civil War and Regional Intervention Summary This report provides information on the ongoing crisis in Yemen. Now in its fourth year, the war in Yemen shows no signs of abating. On June 12, 2018, the Saudi-led coalition, a multinational grouping of armed forces led primarily by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), launched Operation Golden Victory, with the aim of retaking the Red Sea port city of Hudaydah. The coalition also has continued to conduct air strikes inside Yemen. The war has killed thousands of Yemenis, including combatants as well as civilians, and has significantly damaged the country’s infrastructure. According to the United Nations (U.N.) High Commissioner for Human Rights, from the start of the conflict in March 2015 through August 9, 2018, the United Nations documented “a total of 17,062 civilian casualties—6,592 dead and 10,470 injured.” This figure may vastly underestimate the war’s death toll. Although both the Obama and Trump Administrations have called for a political solution to the conflict, the war’s combatants still appear determined to pursue military victory. The two sides also appear to fundamentally disagree over the framework for a potential political solution. The Saudi-led coalition demands that the Houthi militia disarm, relinquish its heavy weaponry (ballistic missiles and rockets), and return control of the capital, Sanaa, to the internationally recognized government of President Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, who is in exile in Saudi Arabia. -

Security and Humanitarian Situation

Country Information and Guidance Yemen: Security and humanitarian situation Version 1.0 November 2015 Preface This document provides country of origin information (COI) and guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling particular types of protection and human rights claims. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the guidance contained with this document; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Country Information The COI within this document has been compiled from a wide range of external information sources (usually) published in English. Consideration has been given to the relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability of the information and wherever possible attempts have been made to corroborate the information used across independent sources, to ensure accuracy. All sources cited have been referenced in footnotes. It has been researched and presented with reference to the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, dated July 2012. Feedback Our goal is to continuously improve the guidance and information we provide. Therefore, if you would like to comment on this document, please e-mail us. -

Download the Full Report

H U M A N R I G H T S “A Life-Threatening Career” Attacks on Journalists under Yemen’s New Government WATCH “A Life-Threatening Career” Attacks on Journalists under Yemen’s New Government Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-30374 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2013 ISBN: 978-1-6231-30374 "A Life-Threatening Career" Attacks on Journalists under Yemen’s New Government Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 Recommendations ........................................................................................................ -

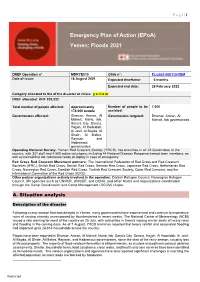

Emergency Plan of Action (Epoa) Yemen: Floods 2021

P a g e | 1 Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Yemen: Floods 2021 DREF Operation n° MDRYE010 Glide n°: FL-2021-000110-YEM Date of issue: 16 August 2021 Expected timeframe: 6 months Expected end date: 28 February 2022 Category allocated to the of the disaster or crisis: y e l l o w DREF allocated: CHF 205,332 Total number of people affected: Approximately Number of people to be 7,000 174,000 people assisted: Governorates affected: Dhamar, Amran, Al Governorates targeted: Dhamar, Amran, Al Mahwit, Marib, Ibb, Mahwit, Ibb governorates Sana’a City, Sana’a, Hajjah, Al Hodeidah, Al Jawf, Al Bayda, Al Dhale, Al Mahra, Raymah and Hadramout governorates Operating National Society: Yemen Red Crescent Society (YRCS) has branches in all 22 Governates of the country, with 321 staff and 4,500 active volunteers, including 44 National Disaster Response trained team members, as well as trained first aid volunteers ready to deploy in case of emergency. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners: The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), British Red Cross, Danish Red Cross, German Red Cross, Japanese Red Cross, Netherlands Red Cross, Norwegian Red Cross, Swedish Red Cross, Turkish Red Crescent Society, Qatar Red Crescent, and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Danish Refugee Council, Norwegian Refugee Council, UN agencies such as UNHCR, UNICEF, and OCHA, and other NGOs and organizations coordinated through the Camp Coordination and Camp Management (CCCM) cluster. A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster Following a rainy season that was delayed in Yemen, many governorates have experienced and continue to experience rains of varying intensity accompanied by thunderstorms in recent weeks. -

The Role of Elections in a Post-Conflict Yemen

The Role of Elections in a Post-Conflict Yemen April 2016 The Role of Elections in a Post-Conflict Yemen Copyright © 2016 International Foundation for Electoral Systems. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the written permission of IFES. Please send all requests for permission to: International Foundation for Electoral Systems 2011 Crystal Drive, 10th Floor Arlington, VA 22202 Email: [email protected] Fax: 202.350.6701 About IFES The International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) supports citizens’ right to participate in free and fair elections. Our independent expertise strengthens electoral systems and builds local capacity to deliver sustainable solutions. As the global leader in democracy promotion, we advance good governance and democratic rights by: Providing technical assistance to election officials Empowering the underrepresented to participate in the political process Applying field-based research to improve the electoral cycle Since 1987, IFES has worked in over 145 countries – from developing democracies, to mature democracies. For more information, visit www.IFES.org. Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 1 1. The Current Political Situation in Yemen ............................................................................................. -

Unification in Yemen

UNIFICATION IN YEMEN Dynamics of Political Integration, 1978-2000 Sharif Ismail Wadham College Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of MPhil in Modern Middle Eastern Studies Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford 1 Contents Acknowledgements 3 List of Abbreviations 4 Maps 5 1. Introduction 10 2. Theories and Methods 12 Deutsch, Security Communities and the Pluralist Model 12 The Challenge from Functionalism and Neo-functionalism 14 Federalism and Lessons from Etzioni 14 Migdal and the Question of ‘Social Control’ 15 Towards a Synthesis 16 Methodology 17 3. Reviewing Elite-centred Histories of Unification 19 Constrained State-building, Accommodation and Co-option in the YAR 19 Weakening State Control in the PDRY 21 The Enduring Theme: discourses of a united Yemen 23 Explaining Unification 23 Elite-level Politics in the Transition Period 25 Elite-level Politics after 1994: S!lih and the GPC triumphant 28 4. Coercive Contest: the limits of the state’s attempts to enforce integration 30 Theoretical Considerations 30 The Situation in the North pre-1990 31 The Situation in the South pre-1990 34 The Transition Period 37 The Civil War 39 The Post-War Impasse: negotiating a limited ‘Security State’ 40 Conclusion 43 5. The Battle for Control of Yemen’s Water Resources 45 Theoretical Considerations 45 The Situation in the North pre-1990 46 The Situation in the South pre-1990 48 The Transition Period 51 Political Compromise, 1994-2000: the limits of state control 53 Conclusion 55 6. Defining a New National Discourse in the Education Sector 56 Theoretical Considerations 56 The Situation in the North pre-1990 56 The Situation in the South pre-1990 60 The Transition Period 63 Negotiating the Education Agenda, 1994-2000 67 Conclusion 69 7.