The War in Yemen: 2011-2018: the Elusive Road to Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

H-Diplo Roundtable, Vol. XV, No. 6

2013 Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane H-Diplo Labrosse Roundtable Web/Production Editor: George Fujii H-Diplo Roundtable Review www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Commissioned for H-Diplo by Thomas Maddux Volume XV, No. 6 (2013) 7 October 2013 Introduction by Fred H. Lawson Jesse Ferris. Nasser’s Gamble: How Intervention in Yemen Caused the Six-Day War and the Decline of Egyptian Power. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013. ISBN: 9780691155142 (cloth, $45.00/£30.95). Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-XV-6.pdf Contents Introduction by Fred H. Lawson, Mills College ......................................................................... 2 Review by J.E. Peterson, Tucson, Arizona ................................................................................. 4 Review by Yaacov Ro’i, Tel-Aviv University .............................................................................. 6 Review by Salim Yaqub, University of California, Santa Barbara ............................................. 9 Author’s Response by Jesse Ferris, Israel Democracy Institute.............................................. 12 Copyright © 2013 H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online. H-Net permits the redistribution and reprinting of this work for non-profit, educational purposes, with full and accurate attribution to the author(s), web location, date of publication, H-Diplo, and H-Net: Humanities & Social Sciences Online. For other uses, contact the H-Diplo editorial staff at [email protected]. H-Diplo -

Yemen in Crisis

A Conflict Overlooked: Yemen in Crisis Jamison Boley Kent Evans Sean Grassie Sara Romeih Conflict Risk Diagnostic 2017 Conflict Background Yemen has a weak, highly decentralized central government that has struggled to rule the northern Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) and the southern People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY).1 Since the unification of these entities in 1990, Yemen has experienced three civil conflicts. As the poorest country in the Arab world, Yemen faces serious food and water shortages for a population dispersed over mountainous terrain.2 The country’s weaknesses have been exploited by Saudi Arabia which shares a porous border with Yemen. Further, the instability of Yemen’s central government has created a power vacuum filled by foreign states and terrorist groups.3 The central government has never had effective control of all Yemeni territory. Ali Abdullah Saleh, who was president of Yemen for 34 years, secured his power through playing factions within the population off one another. The Yemeni conflict is not solely a result of a Sunni-Shia conflict, although sectarianism plays a role.4 The 2011 Arab Spring re-energized the Houthi movement, a Zaydi Shia movement, which led to the overthrow of the Saleh government. Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi took office as interim president in a transition led by a coalition of Arab Gulf states and backed by the United States. Hadi has struggled to deal with a variety of problems, including insurgency, the continuing loyalty of many military officers to former president Saleh, as well as corruption, unemployment and food insecurity.5 Conflict Risk Diagnostic Indicators Key: (+) Stabilizing factor; (-) Destabilizing factor; (±) Mixed factor Severe Risk - Government military expenditures have been generally stable between 2002-2015, at an average of 4.8% of GDP. -

Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan

Fall 08 September 2012 Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians From US Drone Practices in Pakistan International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic Stanford Law School Global Justice Clinic http://livingunderdrones.org/ NYU School of Law Cover Photo: Roof of the home of Faheem Qureshi, a then 14-year old victim of a January 23, 2009 drone strike (the first during President Obama’s administration), in Zeraki, North Waziristan, Pakistan. Photo supplied by Faheem Qureshi to our research team. Suggested Citation: INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION CLINIC (STANFORD LAW SCHOOL) AND GLOBAL JUSTICE CLINIC (NYU SCHOOL OF LAW), LIVING UNDER DRONES: DEATH, INJURY, AND TRAUMA TO CIVILIANS FROM US DRONE PRACTICES IN PAKISTAN (September, 2012) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I ABOUT THE AUTHORS III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS V INTRODUCTION 1 METHODOLOGY 2 CHALLENGES 4 CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 7 DRONES: AN OVERVIEW 8 DRONES AND TARGETED KILLING AS A RESPONSE TO 9/11 10 PRESIDENT OBAMA’S ESCALATION OF THE DRONE PROGRAM 12 “PERSONALITY STRIKES” AND SO-CALLED “SIGNATURE STRIKES” 12 WHO MAKES THE CALL? 13 PAKISTAN’S DIVIDED ROLE 15 CONFLICT, ARMED NON-STATE GROUPS, AND MILITARY FORCES IN NORTHWEST PAKISTAN 17 UNDERSTANDING THE TARGET: FATA IN CONTEXT 20 PASHTUN CULTURE AND SOCIAL NORMS 22 GOVERNANCE 23 ECONOMY AND HOUSEHOLDS 25 ACCESSING FATA 26 CHAPTER 2: NUMBERS 29 TERMINOLOGY 30 UNDERREPORTING OF CIVILIAN CASUALTIES BY US GOVERNMENT SOURCES 32 CONFLICTING MEDIA REPORTS 35 OTHER CONSIDERATIONS -

Iran's Proxy War in Yemen

ISBN 978-9934-564-68-0 IRAN’S PROXY WAR IN YEMEN: THE INFORMATION WARFARE LANDSCAPE Published by the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence ISBN: 978-9934-564-68-0 Authors: Dr. Can Kasapoglu, Mariam Fekry Content Editor: Anna Reynolds Project manager: Giorgio Bertolin Design: Kārlis Ulmanis Riga, January 2020 NATO StratCom COE 11b Kalnciema iela Riga LV-1048, Latvia www.stratcomcoe.org Facebook/Twitter: @stratcomcoe This report draws on source material that was available by September 2019. This publication does not represent the opinions or policies of NATO or NATO StratCom COE. © All rights reserved by the NATO StratCom COE. Reports may not be copied, reproduced, distributed or publicly displayed without reference to the NATO StratCom COE. The views expressed here do not represent the views of NATO. Contents Executive summary ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 4 Introduction and geopolitical context . ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 4 Military-strategic background ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 5 Iranian & iran-backed political warfare and information activities 10 Analysis of information operations and conclusions ����������������������������������������������������������� 14 Linguistic assessment of Houthi information activities vis-à-vis kinetic actions on the ground �������������� 14 Assessment of pro-Iranian -

Security Council Distr.: General 27 January 2020

United Nations S/2020/70 Security Council Distr.: General 27 January 2020 Original: English Letter dated 27 January 2020 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council The members of the Panel of Experts on Yemen have the honour to transmit herewith the final report of the Panel, prepared in accordance with paragraph 6 of resolution 2456 (2019). The report was provided to the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 2140 (2014) on 27 December 2019 and was considered by the Committee on 10 January 2020. We would appreciate it if the present letter and the report were brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Dakshinie Ruwanthika Gunaratne Coordinator Panel of Experts on Yemen (Signed) Ahmed Himmiche Expert (Signed) Henry Thompson Expert (Signed) Marie-Louise Tougas Expert (Signed) Wolf-Christian Paes Expert 19-22391 (E) 070220 *1922391* S/2020/70 Final report of the Panel of Experts on Yemen Summary After more than five years of conflict, the humanitarian crisis in Yemen continues. The country’s many conflicts are interconnected and can no longer be separated by clear divisions between external and internal actors and events. Throughout 2019, the Houthis and the Government of Yemen made little headway towards either a political settlement or a conclusive military victory. In a continuation from 2018, the belligerents continued to practice economic warfare: using economic obstruction and financial tools as weapons to starve opponents of funds or materials. Profiteering from the conflict is endemic. -

Yemen's Relations with the Gulf Cooperation Council

Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States ‘One blood and one destiny’? Yemen’s relations with the Gulf Cooperation Council Edward Burke June 2012 Number 23 The Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States is a ten-year multidisciplinary global research programme. It focuses on topics such as globalization and the repositioning of the Gulf States in the global order, capital flows, and patterns of trade; specific challenges facing carbon-rich and resource-rich economic development; diversification, educational and human capital development into post-oil political economies; and the future of regional security structures in the post-Arab Spring environment. The Programme is based in the LSE Department of Government and led by Professor Danny Quah and Dr Kristian Ulrichsen. The Programme produces an acclaimed working paper series featuring cutting-edge original research on the Gulf, published an edited volume of essays in 2011, supports post-doctoral researchers and PhD students, and develops academic networks between LSE and Gulf institutions. At the LSE, the Programme organizes a monthly seminar series, invitational breakfast briefings, and occasional public lectures, and is committed to five major biennial international conferences. The first two conferences took place in Kuwait City in 2009 and 2011, on the themes of Globalization and the Gulf, and The Economic Transformation of the Gulf. The next conference will take place at the LSE in March 2013, on the theme of The Arab Spring and the Gulf: Politics, Economics, and Security. The Programme is funded by the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 19 June 2019

United Nations A/74/6 (Sect. 3)/Add.2 General Assembly Distr.: General 19 June 2019 Original: English Seventy-fourth session Item 137 of the preliminary list* Proposed programme budget for 2020 Proposed programme budget for 2020 Part II Political affairs Section 3 Political affairs Special political missions Thematic cluster I: special and personal envoys, advisers and representatives of the Secretary-General Summary The present report contains the proposed resource requirements for 2020 for 11 special political missions grouped under the thematic cluster of special and personal envoys, advisers and representatives of the Secretary-General. The proposed resource requirements for 2020 for special political missions grouped under this cluster amount to $57,073,400 (net of staff assessment). * A/74/50. 19-10046 (E) 070819 *1910046* A/74/6 (Sect.3)/Add.2 Contents Page I. Financial overview ............................................................. 4 II. Special political missions ........................................................ 5 1. Office of the Special Adviser to the Secretary-General on Cyprus ................... 5 A. Proposed programme plan for 2020 and programme performance for 2018** ..... 8 B. Proposed post and non-post resource requirements for 2020*** ................ 11 2. Office of the Special Adviser to the Secretary-General on the Prevention of Genocide .. 13 A. Proposed programme plan for 2020 and programme performance for 2018** ..... 18 B. Proposed post and non-post resource requirements for 2020*** ................ 23 3. Personal Envoy of the Secretary-General for Western Sahara....................... 25 A. Proposed programme plan for 2020 and programme performance for 2018** ..... 28 B. Proposed post and non-post resource requirements for 2020*** ................ 31 4. Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for the implementation of Security Council resolution 1559 (2004) .............................................. -

Yemen and The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Research Online Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States ‘One blood and one destiny’? Yemen’s relations with the Gulf Cooperation Council Edward Burke June 2012 Number 23 The Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States is a ten-year multidisciplinary global research programme. It focuses on topics such as globalization and the repositioning of the Gulf States in the global order, capital flows, and patterns of trade; specific challenges facing carbon-rich and resource-rich economic development; diversification, educational and human capital development into post-oil political economies; and the future of regional security structures in the post-Arab Spring environment. The Programme is based in the LSE Department of Government and led by Professor Danny Quah and Dr Kristian Ulrichsen. The Programme produces an acclaimed working paper series featuring cutting-edge original research on the Gulf, published an edited volume of essays in 2011, supports post-doctoral researchers and PhD students, and develops academic networks between LSE and Gulf institutions. At the LSE, the Programme organizes a monthly seminar series, invitational breakfast briefings, and occasional public lectures, and is committed to five major biennial international conferences. The first two conferences took place in Kuwait City in 2009 and 2011, on the themes of Globalization and the Gulf, and The Economic Transformation of the Gulf. The next conference will take place at the LSE in March 2013, on the theme of The Arab Spring and the Gulf: Politics, Economics, and Security. -

Institutional Change and the Egyptian Presence in Yemen 1962-19671

1 Importing the Revolution: Institutional change and the Egyptian presence in Yemen 1962-19671 Joshua Rogers Accepted version. Published 2018 in Marc Owen Jones, Ross Porter and Marc Valeri (eds.): Gulfization of the Arab World. Berlin, London: Gerlach, pp. 113-133. Abstract Between 1962 and 1967, Egypt launched a large-scale military intervention to support the government of the newly formed Yemen Arab Republic. Some 70,000 Egyptian military personnel and hundreds of civilian advisors were deployed with the stated aim to ‘modernize Yemeni institutions’ and ‘bring Yemen out of the Middle Ages.’ This article tells the story of this significant top-down and externally-driven transformation, focusing on changes in the military and formal government administration in the Yemen Arab Republic and drawing on hitherto unavailable Egyptian archival material. Highlighting both the significant ambiguity in the Egyptian state-building project itself, as well as the unintended consequences that ensued as Egyptian plans collided with existing power structures; it traces the impact of Egyptian intervention on new state institutions, their modes of functioning, and the articulation of these ‘modern’ institutions, particularly the military and new central ministries, with established tribal and village-based power structures. 1. Introduction On the night of 26 September 1962, a column of T-34 tanks trundled through the streets of Sana‗a and surrounded the palace of the new Imam of Yemen, Mu ammad al-Badr,2 who had succeeded his father Imam ‘ mad (r.1948-62) only one week earlier. Opening fire shortly before midnight, the Yemeni Free Officers announced the ‗26 September Revolution‘ on Radio Sana‗a and declared the formation of a new state: the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR). -

The Situation in Yemen Subject Specialist: Ben Smith

DEBATE PACK CDP-0069 (2020) | 20 March 2020 Compiled by: Nigel Walker The situation in Yemen Subject specialist: Ben Smith Contents Main Chamber 1. Background 2 2. Press articles 4 Tuesday 24 March 2020 3. Press releases 6 4. PQs 15 General debate 5. Debates 24 6. Statements 25 7. Early Day Motions 29 8. Further reading 32 The proceedings of this debate can be viewed on Parliamentlive.tv. The House of Commons Library prepares a briefing in hard copy and/or online for most non-legislative debates in the Chamber and Westminster Hall other than half-hour debates. Debate Packs are produced quickly after the announcement of parliamentary business. They are intended to provide a summary or overview of the issue being debated and identify relevant briefings and useful documents, including press and parliamentary material. More detailed briefing can be prepared for Members on request to the Library. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Number CDP-0069, 20 March 2020 1. Background The fighting in Yemen has been going on since the failure in 2011 of a Saudi-backed transition from long-time President Saleh to his deputy Abd Rabbuh Mansour al-Hadi. The rebel Houthi movement, based in the North and deeply hostile to the Saudis, took control of much of the country from the Hadi Government, entering the capital, Sanaa, in late 2014. Saudi Arabia arranged a coalition, whose strongest members were Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, to prop up the Hadi Government. The ensuing conflict produced the world’s worst humanitarian disaster, with millions of people at risk from starvation and rampant disease. -

Downloads/Codebook.Pdf

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature: ||||||||||||||| |||||| Goran Pei´c Date Civilian Defense Forces, Tribal Groups, and Counterinsurgency Outcomes By Goran Pei´c Doctor of Philosophy Political Science ||||||||||||||| Dan Reiter Advisor ||||||||||||||| Clifford Carrubba Committee Member ||||||||||||||| Kyle Beardsley Committee Member Accepted: ||||||||||||||| Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies |||||| Date Civilian Defense Forces, Tribal Groups, and Counterinsurgency Outcomes By Goran Pei´c M.A., Villanova University, 2006 Advisor: Dan Reiter, Ph.D. An abstract of a dissertation submitted to the faculty of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies of Emory University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science 2013 ABSTRACT Civilian Defense Forces, Tribal Groups, and Counterinsurgency Outcomes By Goran Pei´c How do states maintain their authority given that even weak non-state groups are now capable of challenging states by resorting to irregular warfare? In Part I of the dissertation, I propose that one of the ways in which states pursue internal se- curity is by recruiting civilians into lightly armed self-defense units referred to as civilian defense forces (CDFs). -

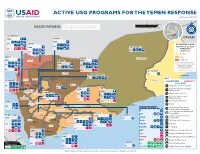

USG Yemen Complex Emergency Program

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE YEMEN RESPONSE Last Updated 02/12/20 0 50 100 mi INFORMA Partner activities are contingent upon access to IC TI PH O A N R U G SAUDI ARABIA conict-aected areas and security concerns. 0 50 100 150 km N O I T E G U S A A D ID F /DCHA/O AL HUDAYDAH IOM AMRAN OMAN IOM IPs SA’DAH ESTIMATED FOOD IPs SECURITY LEVELS IOM HADRAMAWT IPs THROUGH IPs MAY 2020 IPs Stressed HAJJAH Crisis SANA’A Hadramawt IOM Sa'dah AL JAWF IOM Emergency An “!” indicates that the phase IOM classification would likely be worse IPs Sa'dah IPs without current or planned IPs humanitarian assistance. IPs Source: FEWS NET Yemen IPs AL MAHRAH Outlook, 02/20 - 05/20 Al Jawf IP AMANAT AL ASIMAH Al Ghaedha IPs KEY Hajjah Amran Al Hazem AL MAHWIT Al Mahrah USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP State/PRM Marib IPs Hajjah Amran MARIB Agriculture and Food Security SHABWAH IPs IBB Camp Coordination and Camp Al Mahwit IOM IPs Sana'a Management Al Mahwit IOM DHAMAR Sana'a IPs Cash Transfers for Food Al IPs IPs Economic Recovery and Market Systems Hudaydah IPs IPs Food Voucher Program RAYMAH IPs Dhamar Health Raymah Al Mukalla IPs Shabwah Ataq Dhamar COUNTRYWIDE Humanitarian Coordination Al Bayda’ and Information Management IP Local, Regional, and International Ibb AD DALI’ Procurement TA’IZZ Al Bayda’ IOM Ibb ABYAN IOM Al BAYDA’ Logistics Support and Relief Ad Dali' OCHA Commodities IOM IOM IP Ta’izz Ad Dali’ Abyan IPs WHO Multipurpose Cash Assistance Ta’izz IPs IPs UNHAS Nutrition Lahij IPs LAHIJ Zinjubar UNICEF Protection IPs IPs WFP Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food IOM Al-Houta ADEN FAO Refugee and Migrant Assistance IPs Aden IOM UNICEF Risk Management Policy and Practice Shelter and Settlements IPs WFP SOCOTRA DJIBOUTI, ETHIOPIA, U.S.