A New Model for Defeating Al Qaeda in Yemen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CORVINUS UNIVERSITY of BUDAPEST INTERSTATE RIVALS' INTERVENTION in THIRD PARTY CIVIL WARS: the Comparative Case of Saudi Arabi

CORVINUS UNIVERSITY OF BUDAPEST INTERSTATE RIVALS’ INTERVENTION IN THIRD PARTY CIVIL WARS: The comparative case of Saudi Arabia and Iran in Yemen (2004-2018) DOCTORAL DISSERTATION Supervisor: Marton Péter, Phd Associate Professor Palik Júlia Budapest, 2020 Palik Júlia Interstate rivals’ intervention in third-party civil wars: The comparative case of Saudi Arabia and Iran in Yemen (2004-2018) Institute of International Studies Supervisor: Marton Péter,Phd Associate Professor © Palik Júlia Corvinus University of Budapest International Relations Multidisciplinary Doctoral School Interstate rivals’ intervention in third-party civil wars: The comparative case of Saudi Arabia and Iran in Yemen (2004-2018) Doctoral Dissertation Palik Júlia Budapest, 2020 Table of Content List of Tables, Figures, and Maps....................................................................................................................................... 9 Abstract ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................................................... 9 1. RESEARCH DESIGN ................................................................................................................................................. 12 1.2. Methodology ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Tor Yemen Nutrition Cluster Revi

Yemen Nutrition Cluster كتله التغذية اليمن https://www.humanitarianresponse.info https://www.humanitarianresponse.info /en/operations/yemen/nutrition /en/operations/yemen/nutrition XXXXXXXX XXXXXXXX YEMEN NUTRITION CLUSTER TERMS OF REFERENCE Updated 23 April 2018 1. Background Information: The ‘Cluster Approach1’ was adopted by the interagency standing committee as a key strategy to establish coordination and cooperation among humanitarian actors to achieve more coherent and effective humanitarian response. At the country level, the aim is to establish clear leadership and accountability for international response in each sector and to provide a framework for effective partnership and to facilitat strong linkages among international organization, national authorities, national civil society and other stakeholders. The cluster is meant to strengthen rather than to replace the existing coordination structure. In September 2005, IASC Principals agreed to designate global Cluster Lead Agencies (CLA) in critical programme and operational areas. UNICEF was designated as the Global Nutrition Cluster Lead Agency (CLA). The nutrition cluster approach was adopted and initiated in Yemen in August 2009, immediately after the break-out of the sixth war between government forces and the Houthis in Sa’ada governorate in northern Yemen. Since then Yemen has continued to face complex emergencies that are largely conflict-generated and in part aggravated by civil unrest and political instability. These complex emergencies have come on the top of an already fragile situation with widespread poverty, food insecurity and underdeveloped infrastructure. Since mid-March 2015, conflict has spread to 20 of Yemen’s 22 governorates, prompting a large-scale protection crisis and aggravating an already dire humanitarian crisis brought on by years of poverty, poor governance and ongoing instability. -

Yemen in Crisis

A Conflict Overlooked: Yemen in Crisis Jamison Boley Kent Evans Sean Grassie Sara Romeih Conflict Risk Diagnostic 2017 Conflict Background Yemen has a weak, highly decentralized central government that has struggled to rule the northern Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) and the southern People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY).1 Since the unification of these entities in 1990, Yemen has experienced three civil conflicts. As the poorest country in the Arab world, Yemen faces serious food and water shortages for a population dispersed over mountainous terrain.2 The country’s weaknesses have been exploited by Saudi Arabia which shares a porous border with Yemen. Further, the instability of Yemen’s central government has created a power vacuum filled by foreign states and terrorist groups.3 The central government has never had effective control of all Yemeni territory. Ali Abdullah Saleh, who was president of Yemen for 34 years, secured his power through playing factions within the population off one another. The Yemeni conflict is not solely a result of a Sunni-Shia conflict, although sectarianism plays a role.4 The 2011 Arab Spring re-energized the Houthi movement, a Zaydi Shia movement, which led to the overthrow of the Saleh government. Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi took office as interim president in a transition led by a coalition of Arab Gulf states and backed by the United States. Hadi has struggled to deal with a variety of problems, including insurgency, the continuing loyalty of many military officers to former president Saleh, as well as corruption, unemployment and food insecurity.5 Conflict Risk Diagnostic Indicators Key: (+) Stabilizing factor; (-) Destabilizing factor; (±) Mixed factor Severe Risk - Government military expenditures have been generally stable between 2002-2015, at an average of 4.8% of GDP. -

Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen's Red Sea Coast

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) Art History Faculty Scholarship Art History 2017 “Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast.” In ‘Architecture That Fills My Eye’: The Building Heritage of Yemen. Exh. Cat. Ed. Trevor H.J. Marchand, 60-69. London: Gingko Library, 2017. Nancy Um Binghamton University--SUNY, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/art_hist_fac Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Nancy Um, “Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast.” In ‘Architecture That Fills My Eye’: The Building Heritage of Yemen. Exh. Cat. Ed. Trevor H.J. Marchand, 60-69. London: Gingko Library, 2017. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Art History Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. GINGKO LIBRARY ART SERIES Senior Editor: Melanie Gibson Architectural Heritage of Yemen Buildings that Fill my Eye Edited by Trevor H.J. Marchand First published in 2017 by Gingko Library 70 Cadogan Place, London SW1X 9AH Copyright © 2017 selection and editorial material, Trevor H. J. Marchand; individual chapters, the contributors. The rights of Trevor H. J. Marchand to be identified as the author of the editorial material, and of the individual authors as authors of their contributions, has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Aden Sub- Office May 2020

FACT SHEET Aden Sub- Office May 2020 Yemen remains the world’s Renewed fighting in parts of UNHCR and partners worst humanitarian crisis, with the country, torrential rains provide protection and more than 14 million people and deadly flash floods and assistance to displaced requiring urgent protection and now a pandemic come to families, refugees, asylum- assistance to access food, water, exacerbate the already dire seekers and their host shelter and health. situation of millions of people. communities. KEY INDICATORS 1,082,430 Number of internally displaced persons in the south DTM March 2019 752,670 Number of returnees in the south DTM March 2019 161,000 UNHCR’s partner staff educate a Yemeni man on COVID-19 and key Number of refugees and asylum seekers in the preventive measures during a door-to-door distribution of hygiene material south UNHCR April 2020 including soap, detergent in Basateen, in Aden © UNHCR/Mraie-Joelle Jean-Charles, April 2020. UNHCR PRESENCE Staff: 85 National Staff 14 International Staff Offices: 1 Sub Office in Aden 1 Field Office in Kharaz 2 Field Units in Al Mukalla and Turbah www.unhcr.org 1 FACT SHEET > Aden Sub- Office/ May 2020 Main activities Protection INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS Protection Cluster ■ The Protection Cluster led by UNHCR and co-led by Intersos coordinates the delivery of specialised assistance to people with specific protection needs, including victims of violence and support to community centres, programmes, and protection networks. ■ At the Sub-National level, the Protection Cluster includes more than 40 partners. ■ UNHCR seeks to widen the protection space through protection monitoring (at community and household levels) and provision of protection services including legal, psychosocial support, child protection and prevention and response to sexual and gender-based violence. -

Provision of Technical Support/Services for an Economical

A project financed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark Provision of Technical Support/Services for an Economical, Technological and Environmental Impact Assessment of National Regulations and Incentives for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Country Report Yemen January 2010, revised April 2010 Norsk-Data-Str. 1 Döppersberg 19 61352 Bad Homburg, Germany 42103 Wuppertal, Germany Tel: +49-6172-9460-103, Fax. +49-6172-9460-20 Tel: +49-202-2492-0, Fax: +49-202-2492-108 eMail: [email protected] eMail: [email protected] http://www.mvv-decon.com http://www.wupperinst.org Table of Contents Page 1. Project Synopsis 1 2. Summary of Energy Situation in Yemen 2 3. Comparison of Yemeni Practice with International Practice in Energy Efficiency 4 3.1 Strategy 4 3.2 Legal Reform 6 3.3 Price Reform 6 3.4 An Agency 8 3.5 Standards and / or Labels 9 3.6 Financial Incentives 10 3.7 Obligations 11 3.8 Audits and the Promotion of ESCOs 12 3.9 Transport and Spatial Planning 12 3.10 Dissemination of Information 13 4. Comparison of Yemeni Practice with International Practice in Renewable Energy 14 4.1 Targets and Strategy 14 4.2 Legal Reform 16 4.3 An Agency 18 4.4 Standards and /or Labels 19 4.5 Financial Incentives (Capital Support) 19 4.6 Feed-in Tariffs and Obligations 20 4.7 CDM Finance 21 4.8 Information 22 4.9 Industrial Policy 22 5. Case Studies 24 5.1 Case Study 1 - Efficient Lighting in Public Buildings 24 5.1.1 Background and Context 24 5.1.1.1 Programme of Activities 24 5.1.1.2 The Lighting market in Yemen 25 -

Tribes and Politics in Yemen

Arabian Peninsula Background Notes APBN-007 December 2008 Tribes and Politics in Yemen Yemen’s government is not a tribal regime. The Tribal Nature of Yemen Yet tribalism pervades Yemeni society and influences and limits Yemeni politics. The ‘Ali Yemen, perhaps more than any other state ‘Abdullah Salih regime depends essentially on in the Arab world, is fundamentally a tribal only two tribes, although it can expect to rely society and nation. To a very large degree, on the tribally dominated military and security social standing in Yemen is defined by tribal forces in general. But tribesmen in these membership. The tribesman is the norm of institutions are likely to be motivated by career society. Other Yemenis either hold a roughly considerations as much or more than tribal equal status to the tribesman, for example, the identity. Some shaykhs also serve as officers sayyids and the qadi families, or they are but their control over their own tribes is often inferior, such as the muzayyins and the suspect. Many tribes oppose the government akhdam. The tribes in Yemen hold far greater in general on grounds of autonomy and self- importance vis-à-vis the state than elsewhere interest. The Republic of Yemen (ROY) and continue to challenge the state on various government can expect to face tribal resistance levels. At the same time, a broad swath of to its authority if it moves aggressively or central Yemen below the Zaydi-Shafi‘i divide – inappropriately in both north and south. But including the highlands north and south of it should be stressed that tribal attitudes do Ta‘izz and in the Tihamah coastal plain – not differ fundamentally from the attitudes of consists of a more peasantized society where other Yemenis and that tribes often seek to tribal ties and reliance is muted. -

The Adaptive Transformation of Yemen?S Republican Guard

The Adaptive Transformation of Yemen's Republican Guard By Lucas Winter Journal Article | Mar 7 2017 - 9:45pm The Adaptive Transformation of Yemen’s Republican Guard Lucas Winter In the summer of 1978, Colonel Ali Abdullah Saleh became president of the Yemeni Arab Republic (YAR) or North Yemen. Like his short-lived predecessor Ahmad al-Ghashmi, Saleh had been a tank unit commander in the YAR military before ascending the ranks.[1] Like al-Ghashmi, Saleh belonged to a tribe with limited national political influence but a strong presence in the country’s military.[2] Three months into Saleh’s presidency, conspirators allied with communists from the Popular Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY), or South Yemen, staged a coup and briefly seized key government installations in the capital Sana’a. The 1st Armored Brigade, North Yemen’s main tank unit at the time, was deployed to quell the insurrection. The 1st Armored Brigade subsequently expanded to become the 1st Armored Division. Commanded by Saleh’s kinsman Ali Muhsin al-Ahmar, it became North Yemen’s premiere military unit and took control of vital installations in the capital. The division played a decisive role in securing victory for Saleh and his allies in Yemen’s 1994 Civil War. Although the 1st Armored Division functioned as President Saleh’s Praetorian Guard, his personal safety was in the hands of the Yemeni Republican Guard (YRG), a small force created with Egyptian support in the early days of the republic.[3] YRG headquarters were in “Base 48,” located on the capital’s southern outskirts abutting the territories of Saleh’s Sanhan tribe. -

Security Council Distr.: General 27 January 2020

United Nations S/2020/70 Security Council Distr.: General 27 January 2020 Original: English Letter dated 27 January 2020 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council The members of the Panel of Experts on Yemen have the honour to transmit herewith the final report of the Panel, prepared in accordance with paragraph 6 of resolution 2456 (2019). The report was provided to the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 2140 (2014) on 27 December 2019 and was considered by the Committee on 10 January 2020. We would appreciate it if the present letter and the report were brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Dakshinie Ruwanthika Gunaratne Coordinator Panel of Experts on Yemen (Signed) Ahmed Himmiche Expert (Signed) Henry Thompson Expert (Signed) Marie-Louise Tougas Expert (Signed) Wolf-Christian Paes Expert 19-22391 (E) 070220 *1922391* S/2020/70 Final report of the Panel of Experts on Yemen Summary After more than five years of conflict, the humanitarian crisis in Yemen continues. The country’s many conflicts are interconnected and can no longer be separated by clear divisions between external and internal actors and events. Throughout 2019, the Houthis and the Government of Yemen made little headway towards either a political settlement or a conclusive military victory. In a continuation from 2018, the belligerents continued to practice economic warfare: using economic obstruction and financial tools as weapons to starve opponents of funds or materials. Profiteering from the conflict is endemic. -

June 2013 - February 2014

Yemen outbreak June 2013 - February 2014 Desert Locust Information Service FAO, Rome www.fao.org/ag/locusts Keith Cressman (Senior Locust Forecasting Officer) SAUDI ARABIA spring swarm invasion (June) summer breeding area Thamud YEMEN Sayun June 2013 Marib Sanaa swarms Ataq July 2013 groups April and May 2013 rainfall totals adults 25 50 100+ mm Aden hoppers source: IRI RFE JUN-JUL 2013 Several swarms that formed in the spring breeding areas of the interior of Saudi Arabia invaded Yemen in June. Subsequent breeding in the interior due to good rains in April-May led to an outbreak. As control operations were not possible because of insecurity and beekeepers, hopper and adult groups and small hopper bands and adult swarms formed. DLIS Thamud E M P T Y Q U A R T E R summer breeding area SEP Suq Abs Sayun winter Marib Sanaa W. H A D H R A M A U T breeding area Hodeidah Ataq Aug-Sep 2013 swarms SEP bands groups adults Aden breeding area winter hoppers AUG-SEP 2013 Breeding continued in the interior, giving rise to hopper bands and swarms by September. Survey and control operations were limited due to insecurity and beekeeping and only 5,000 ha could be treated. Large areas could not be accessed where bands and swarms were probably forming. Adults and adult groups moved to the winter breeding areas along the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden coasts where early first generation egg-laying and hatching caused small hopper groups and bands to DLIS form. Ground control operations commenced on 27 September. -

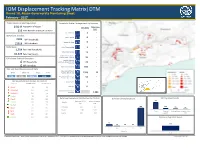

IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix|DTM Round 16, Abyan Governorate Monitoring Sheet February - 2017

IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix|DTM Round 16, Abyan Governorate Monitoring Sheet February - 2017 Total Governorate Population Household Shelter Arrangements by Location 2 Population of Abyan 1 0.56 M IDPs (HH) Returnees (HH) 116 Total Number of Unique Locations School Buildings 2 - IDPs from Conflict Health Facilities 0 - 2103 IDP Households Religious Buildings 0 - 12618 IDP Individuals Returnees Other Private Building 5 - 1,754 Returnee Households Other Public Building 15 - 10,524 Returnee Persons Settlements (Grouped of Families) Urban and Rural - IDPs from Natural Disasters 24 Isolated/ dispersed IDP Households settlements (detatched from 26 - 0 a location) IDP Individuals 0 Rented Accomodation 650 - Sex and Age Dissagregated Data Host Families Who are Men Women Boys Girls Relatives (no rent fee) 1326 70 21% 23% 25% 31% Host Families Who are not Relatives (no rent fee) 54 - IDP Household Distribution Per District Second Home 1 - District IDP HH in Jan IDP HH in Feb Ahwar 32 29 Unknown 0 - Al Mahfad 379 264 Original House of Habitual Al Wade'a 110 96 Residence 1,684 Jayshan 15 25 Khanfir 505 499 Returnee Household Distribution Per District Duration of Displacement IDP Top Most Needs Returnee HH in Returnee HH in 79% Lawdar 259 278 District Jan Feb Mudiyah 34 35 Al Wade'a 130 130 92% 12% 6% Rasad 241 201 2% Khanfir 1,200 1,200 Sarar 121 114 Food Financial Drinking Water Household Items Lawdar 424 424 support (NFI) Sibah 248 221 Zingibar 221 341 Returnee Top Most Needs 8% 0% 0% 0% 100% 1-3 4-6 7-9 10-12 12 > Months Food 1 Population -

Combating Corruption in Yemen

Beyond the Business as Usual Approach: COMBATING CORRUPTION IN YEMEN By: The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies November 2018 COMBATING CORRUPTION IN YEMEN Beyond the Business as Usual Approach: COMBATING CORRUPTION IN YEMEN By: The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies November 2018 This white paper was prepared by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, in coordination with the project partners DeepRoot Consulting and CARPO – Center for Applied Research in Partnership with the Orient. Note: This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union and the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to Yemen. The recommendations expressed within this document are the personal opinions of the author(s) only, and do not represent the views of the Sanaa Center for Strategic Studies, DeepRoot Consulting, CARPO - Center for Applied Research in Partnership with the Orient, or any other persons or organizations with whom the participants may be otherwise affiliated. The contents of this document can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union or the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to Yemen. Co-funded by the European Union Photo credit: Claudiovidri / Shutterstock.com Rethinking Yemen’s Economy | November 2018 2 COMBATING CORRUPTION IN YEMEN TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 3 Acronyms 4 Executive Summary 5 Introduction 8 State Capture Under Saleh 10 Origins of Saleh’s Patronage System 10 Main Beneficiaries of State Capture and Administrative Corruption 12 Maintaining