VULCAN HISTORICAL REVIEW VOLUME 24 2 VULCAN HISTORICAL REVIEW VOLUME 24 Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2019 Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927 Ryan C. Ferro University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ferro, Ryan C., "Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7785 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist-Guomindang Split of 1927 by Ryan C. Ferro A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-MaJor Professor: Golfo Alexopoulos, Ph.D. Co-MaJor Professor: Kees Boterbloem, Ph.D. Iwa Nawrocki, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 8, 2019 Keywords: United Front, Modern China, Revolution, Mao, Jiang Copyright © 2019, Ryan C. Ferro i Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………….…...ii Chapter One: Introduction…..…………...………………………………………………...……...1 1920s China-Historiographical Overview………………………………………...………5 China’s Long -

The Limits of “Diversity” Where Affirmative Action Was About Compensatory Justice, Diversity Is Meant to Be a Shared Benefit

The Limits of “Diversity” Where affirmative action was about compensatory justice, diversity is meant to be a shared benefit. But does the rationale carry weight? By Kelefa Sanneh, THE NEW YORKER, October 9, 2017 This summer, the Times reported that, under President Trump, the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice had acquired a new focus. The division, which was founded in 1957, during the fight over school integration, would now be going after colleges for discriminating against white applicants. The article cited an internal memo soliciting staff lawyers for “investigations and possible litigation related to intentional race-based discrimination in college and university admissions.” But the memo did not explicitly mention white students, and a spokesperson for the Justice Department charged that the story was inaccurate. She said that the request for lawyers related specifically to a complaint from 2015, when a number of groups charged that Harvard was discriminating against Asian-American students. In one sense, Asian-Americans were overrepresented at Harvard: in 2013, they made up eighteen per cent of undergraduates, despite being only about five per cent of the country’s population. But at the California Institute of Technology, which does not employ racial preferences, Asian- Americans made up forty-three per cent of undergraduates—a figure that had increased by more than half over the previous two decades, while Harvard’s percentage had remained relatively flat. The plaintiffs used SAT scores and other data to argue that administrators had made it “far more difficult for Asian-Americans than for any other racial and ethnic group of students to gain admission to Harvard.” They claimed that Harvard, in its pursuit of racial parity, was not only rewarding black and Latino students but also penalizing Asian-American students—who were, after all, minorities, too. -

A War Crime Against an Ally's Civilians: the No Gun Ri Massacre

A WAR CRIME AGAINST AN ALLY'S CIVILIANS: THE NO GUN RI MASSACRE TAE-UNG BAIK* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................ 456 I. THE ANATOMY OF THE No GUN Ri CASE ............ 461 A. Summary of the Incident ......................... 461 1. The Korean War (1950-1953) .............. 461 2. Three Night and Four Day Massacre ....... 463 * Research Intern, Human Rights Watch, Asia Division; Notre Dame Law School, LL.M, 2000, cum laude, Notre Dame Law Fellow, 1999-2001; Seoul National University, LL.B., 1990; Columnist, HANGYORE DAILY NEWSPAPER, 1999; Editor, FIDES, Seoul National University College of Law, 1982-1984. Publi- cations: A Dfferent View on the Kwangju Democracy Movement in 1980, THE MONTHLY OF LABOR LIBERATION LrrERATuRE, Seoul, Korea, May 1990. Former prisonerof conscience adopted by Amnesty International in 1992; released in 1998, after six years of solitary confinement. This article is a revised version of my LL.M. thesis. I dedicate this article to the people who helped me to come out of the prison. I would like to thank my academic adviser, Professor Juan E. Mendez, Director of the Center for Civil and Human Rights, for his time and invaluable advice in the course of writing this thesis. I am also greatly indebted to Associate Director Garth Meintjes, for his assistance and emotional support during my study in the Program. I would like to thank Dr. Ada Verloren Themaat and her husband for supplying me with various reading materials and suggesting the title of this work; Professor Dinah Shelton for her lessons and class discussions, which created the theoreti- cal basis for this thesis; and Ms. -

Untimely Meditations: Reflections on the Black Audio Film Collective

8QWLPHO\0HGLWDWLRQV5HIOHFWLRQVRQWKH%ODFN$XGLR )LOP&ROOHFWLYH .RGZR(VKXQ Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Number 19, Summer 2004, pp. 38-45 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\'XNH8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/nka/summary/v019/19.eshun.html Access provided by Birkbeck College-University of London (14 Mar 2015 12:24 GMT) t is no exaggeration to say that the installation of In its totality, the work of John Akomfrah, Reece Auguiste, Handsworth Songs (1985) at Documentall introduced a Edward George, Lina Gopaul, Avril Johnson, David Lawson, and new audience and a new generation to the work of the Trevor Mathison remains terra infirma. There are good reasons Black Audio Film Collective. An artworld audience internal and external to the group why this is so, and any sus• weaned on Fischli and Weiss emerged from the black tained exploration of the Collective's work should begin by iden• cube with a dramatically expanded sense of the historical, poet• tifying the reasons for that occlusion. Such an analysis in turn ic, and aesthetic project of the legendary British group. sets up the discursive parameters for a close hearing and viewing The critical acclaim that subsequently greeted Handsworth of the visionary project of the Black Audio Film Collective. Songs only underlines its reputation as the most important and We can locate the moment when the YBA narrative achieved influential art film to emerge from England in the last twenty cultural liftoff in 1996 with Douglas Gordon's Turner Prize vic• years. It is perhaps inevitable that Handsworth Songs has tended tory. -

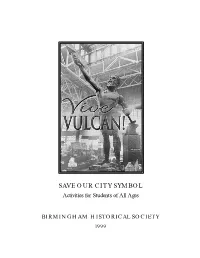

Vulcan! Table of Contents

SAVE OUR CITY SYMBOL Activities for Students of All Ages BIRMINGHAM HISTORICAL SOCIETY 1999 VIVE VULCAN! TABLE OF CONTENTS Teacher Materials A. Overview D. Quiz & Answers B. Activity Ideas E. Word Search Key C. Questions & Answers F. Map of the Ancient World Key Activities 1. The Resumé of a Man of Iron 16. The Red Mountain Revival 2. Birmingham at the Turn 17. National Park Service of the 20th Century Documentation 3. The Big Idea 18. Restoring the Statue 4. The Art Scene 19. A Vision for Vulcan 5. Time Line 20. American Landmarks 6. Colossi of the Ancient World 21. Tallest American Monument 7. Map of the Ancient World 22. Vulcan’s Global Family 8. Vulcan’s Family 23. Quiz 9. Moretti to the Rescue 24. Word Search 10. Recipe for Sloss No. 2 25. Questions Pig Iron 26. Glossary 11. The Foundrymen’s Challenge 27. Pedestal Project 12. Casting the Colossus 28. Picture Page, 13. Meet Me in St. Louis The Birmingham News–Age Herald, 14. Triumph at the Fair Sunday, October 31, 1937 15. Vital Stats On the cover: VULCAN AT THE FAIR. Missouri Historical Society 1035; photographer: Dept. Of Mines & Metallurgy, 1904, St. Louis, Missouri. Cast of iron in Birmingham, Vulcan served as the Birmingham and Alabama exhibit for the St. Louis World’s Fair. As god of the forge, he holds a spearpoint he has just made on his anvil. The spearpoint is of polished steel. In a gesture of triumph, the colossal smith extends his arm upward. About his feet, piles of mineral resources extol Alabama’s mineral wealth and its capability of making colossal quantities of iron, such as that showcased in the statue, and of steel (as demonstrated with the spearpoint). -

Jeremy Scahill Shaun King

JEREMY SCAHILL &SHAUN KING “Reporting on Racial Conflict at Home and Wars Abroad in Wed, March 28, 2018 6:15 - 8 p.m. the Age of Trump” College Avenue Academic Moderated by Building, Room 2400 Juan González, Professor of Professional 15 Seminary Place, Practice, School of Communication and New Brunswick, NJ Information, and co-host of Democracy Now Jeremy Scahill is an investigative reporter, war correspon- dent, and author of the international bestseller Blackwater: The Rise of the World’s Most Powerful Mercenary Army. He has reported from armed conflicts around the world, including Af- ghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, Yemen, Nigeria, and the former Yugo- slavia. He is a two-time winner of the prestigious George Polk Award and produced and wrote the movie Dirty Wars, a doc- umentary that premiered at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival and was nominated for an Academy Award. He is one of the founding editors of the investigative news site The Intercept, where he also hosts the popular weekly podcast Intercepted. In addition, Scahill is the national security correspondent for The Nation and for Democracy Now. Shaun King is nationally known as a civil rights and Black Lives Matter activist, and as an innovator in the use of social media for political change. He currently works as a columnist for The Intercept, where he writes about racial justice, mass incarceration, human rights, and law enforcement misconduct. He has been a senior justice writer at New York’s Daily News, a commentator for The Young Turks and the Tom Joyner Show, a contributing writer to Daily Kos, and a writer-in-residence at Harvard Law School’s Fair Punishment Project. -

Stay Woke, Give Back Virtual Tour Day of Empowerment Featuring Justin Michael Williams

11 1 STAY WOKE, GIVE BACK VIRTUAL TOUR DAY OF EMPOWERMENT FEATURING JUSTIN MICHAEL WILLIAMS On the STAY WOKE, GIVE BACK TOUR, Justin empowers students to take charge of their lives, and their physical and mental wellbeing with mass meditation events at high schools, colleges, and cultural centers across the country. The tour began LIVE in-person in 2020, but now with the Covid crisis—and students and teachers dealing with the stressors of distance learning—we’ve taken the tour virtual, with mass Virtual Assemblies to engage, enliven, and inspire students when they need us most. From growing up with gunshot holes outside of his bedroom window, to sharing the stage with Deepak Chopra, Justin Michael Williams knows the power of healing to overcome. Justin Michael Williams More: StayWokeGiveBack.org Justin is an author, top 20 recording artist, and transformational speaker whose work has been featured by The Wall Street Journal, Grammy.com, Yoga Journal, Billboard, Wanderlust, and South by Southwest. With over a decade of teaching experience, Justin has become a pioneering millennial voice for diversity and inclusion in wellness. What is the Stay Woke Give Back Tour? Even before the start of Covid-19, anxiety and emotional unrest have been plaguing our youth, with suicide rates at an all-time high. Our mission is to disrupt that pattern. We strive to be a part of the solution before the problem starts—and even prevent it from starting in the first place. Instead of going on a traditional “book tour,” Justin is on a “GIVE BACK” tour. At these dynamic Virtual Assemblies—think TED talk meets a music concert—students will receive: • EVENT: private, school-wide Virtual Assembly for entire staff and student body (all tech setup covered by Sounds True Foundation) • LONG-TERM SUPPORT: free access to a 40-day guided audio meditation program, delivered directly to students daily via SMS message every morning, requiring no staff or administrative support. -

Incog- Nito Celeb Jesus Signs

FREE DEADPOOL THEMED INCOG- WIRED HUGS DRESSED PEDA- NITO LOUNGE SOMEONE BADGE SIGN ELSE CAB CELEB GUARDIANS COSPLAY AGENTS CUTE OF THE JESUS THAT’S OF KIDS IN GALAXY TOO HOT SIGNS S.H.I.E.L.D COSPLAY FOR JULY COSPLAY KEVIN ADVENTURE “GEEK” 1 PERSON BATMAN LEGGINGS SMITH W/MANY (AUTO COMIC- TIME WIN) CON BAGS COSPLAY LANYARD ORIGINAL COSPLAYER LINE WITH TMNT PLAYBOY (NO WITH BODY BUNNIES FOR PINS OR PAINT COSPLAY FOOD BLING NOSES) NINTENDO GAME OF SOMEONE NEW SWAG DS THRONES READING BATGIRL FROM ACTUAL PLAYER COSPLAY COMICS COSPLAY STREET TEAM LINE GOTHAM DIS- DOCTOR HELLO FOR KITTY CITY CARDED WHO ANYTHING WATER FOOD P.D. BOTTLE SOMEONE COMIC- FREE T- “GEEK” READING ELF/ CON SHIRT LEGGINGS ACTUAL HAND- VULCAN SELFIES COMICS OUTS EARS A NEW ROCKET RAMONA MYTH- BATGIRL RACOON DISCO NAPPER FLOWERS BUSTER COSPLAY (AUTO BAG WIN) SUPER LONG GUARDIANS MICHEAL GAME OF WIZARD LINE FOR OF THE BAY THRONES STAFF GOD KNOWS GALAXY TMNT COSPLAY WHAT COSPLAY (NOSES) AGENTS SPIRIT CUTE FLYER OF HOOD HAWKEYE KIDS IN ABOUT S.H.I.E.L.D COSPLAY JESUS ORIGINAL SWAG FREE ADVENTURE TMNT DOCTOR FROM WHO HUGS TIME (NO STREET NOSES) TEAM SIGN COSPLAY 1 PERSON SUPER TALL GUARDIANS LANYARD SOMEONE W/MANY SHOES, TOO OF THE WITH READING COMIC- EARLY IN GALAXY ACTUAL PINS OR COMICS CON BAGS THE DAY COSPLAY BLING FEMALE NINTENDO WIL ELF/ COMIC- DEAD- DS WHEATON VULCAN CON PLAYER AUTO EARS SELFIES POOL WIN) HELLO A KITTY JESUS DISCO BATMAN MYTH- ANYTHING NAPPER SIGNS BUSTER SPIRIT DIS- INCOG- WIZARD CARDED RAMONA STAFF HOOD WATER FLOWERS NITO BOTTLE BAG CELEB. -

The Ann Arbor Register. Vol

THE ANN ARBOR REGISTER. VOL. xv. NO. 35. ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY, AUGUST 29, 1889. WHOLE NO. 766. and then a long, loud roll of thunder, then tion of corn is lower, showing only 68 pei Shall Women be Allowed to Vote. A DEMOCRATIC ROW. a shower of cinders and molten stone cent, of an average crop. Potatoes show The question of femal« suffrage has ag- REMNANTS ! REMNANTS! thrown into the air far above our heads. 95 per nent. of a crop, meadow and pas itated the tongues and pens of reformers J. CAVANAUSH'S EVEC- We had to watch closely that none of tures, 97 per cent., clover 98 per cent, for many years and good arguments have TIOJT. these cinders struck us. A period of hay 91 per cent., and apples 73 per cent been adduced for and against it. Many silence for about a quarter of a minute In Washtenaw county the estimate o of the softer sex would vote intelligibly A Big Fight in the Democratic Ranks and then another belching forth of molten crops is as follows : Wheat 13,45 bushels and maDy of them would vote as their hus- Over the Division of the Spoils.— matter. It now got too hot for us and we per acre; corn 70 per cent.; oals 38 bush- bands did, and give no thought to the A Strong Effort to Defeat Car- Mack & Schmid. were obliged to descend a short way els per acre; potatoes 94 percent; hay 8i merits of a political issue. They would anansli but he Secured per cent.; apples 83 per cent. -

Stephan Langton

HDBEHT W WDDDHUFF LIBRARY STEPHAN LANGTON. o o a, H z u ^-^:;v. en « ¥ -(ft G/'r-' U '.-*<-*'^f>-/ii{* STEPHAN LANGTON OR, THE DATS OF KING JOHN M. F- TUPPER, D.C.L., F.R.S., AUTHOR OF "PROVERBIAL PHILOSOPHY," "THREE HUNDRED SONNETS,' "CROCK OF GOLD," " OITHARA," "PROTESTANT BALLADS,' ETC., ETC. NEW EDITION, FRANK LASHAM, 61, HIGH STREET, GUILDFORD. OUILDFORD : ORINTED BY FRANK LA3HAM, HIGH STI;EET PREFACE. MY objects in writing " Stephan Langton " were, first to add a Dcw interest to Albury and its neighbourhood, by representing truly and historically our aspects in the rei"n of King John ; next, to bring to modem memory the grand character of a great and good Archbishop who long antedated Luther in his opposition to Popery, and who stood up for English freedom, ctilminating in Magna Charta, many centuries before these onr latter days ; thirdly, to clear my brain of numeroua fancies and picturea, aa only the writing of another book could do that. Ita aeed is truly recorded in the first chapter, as to the two stone coffins still in the chancel of St. Martha's. I began the book on November 26th, 1857, and finished it in exactly eight weeks, on January 2l8t, 1858, reading for the work included; in two months more it waa printed by Hurat and Blackett. I in tended it for one fail volume, but the publishers preferred to issue it in two scant ones ; it has since been reproduced as one railway book by Ward and Lock. Mr. Drummond let me have the run of his famoua historical library at Albury for purposes of reference, etc., beyond what I had in my own ; and I consulted and partially read, for accurate pictures of John's time in England, the histories of Tyrrell, Holinshed, Hume, Poole, Markland ; Thomson's " Magna Charta," James's " Philip Augustus," Milman's "Latin Christi anity," Hallam's "Middle Agea," Maimbourg'a "LivesofthePopes," Banke't "Life of Innocent the Third," Maitland on "The Dark VllI PKEhACE. -

The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860

PRESERVING THE WHITE MAN’S REPUBLIC: THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN CONSERVATISM, 1847-1860 Joshua A. Lynn A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Harry L. Watson William L. Barney Laura F. Edwards Joseph T. Glatthaar Michael Lienesch © 2015 Joshua A. Lynn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joshua A. Lynn: Preserving the White Man’s Republic: The Democratic Party and the Transformation of American Conservatism, 1847-1860 (Under the direction of Harry L. Watson) In the late 1840s and 1850s, the American Democratic party redefined itself as “conservative.” Yet Democrats’ preexisting dedication to majoritarian democracy, liberal individualism, and white supremacy had not changed. Democrats believed that “fanatical” reformers, who opposed slavery and advanced the rights of African Americans and women, imperiled the white man’s republic they had crafted in the early 1800s. There were no more abstract notions of freedom to boundlessly unfold; there was only the existing liberty of white men to conserve. Democrats therefore recast democracy, previously a progressive means to expand rights, as a way for local majorities to police racial and gender boundaries. In the process, they reinvigorated American conservatism by placing it on a foundation of majoritarian democracy. Empowering white men to democratically govern all other Americans, Democrats contended, would preserve their prerogatives. With the policy of “popular sovereignty,” for instance, Democrats left slavery’s expansion to territorial settlers’ democratic decision-making. -

Archival Documentation, Historical Perception, and the No Gun Ri Massacre in the Korean War

RECORDS AND THE UNDERSTANDING OF VIOLENT EVENTS: ARCHIVAL DOCUMENTATION, HISTORICAL PERCEPTION, AND THE NO GUN RI MASSACRE IN THE KOREAN WAR by Donghee Sinn B.A., Chung-Ang University, 1993 M.A., Chung-Ang University, 1996 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Department of Library and Information Science School of Information Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SCIENCE SCHOOL OF INFORMATION SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Donghee Sinn It was defended on July 9, 2007 and approved by Richard J. Cox, Ph.D., DLIS, Advisor Karen F. Gracy, Ph.D., DLIS Ellen G. Detlefsen, Ph.D., DLIS Jeannette A. Bastian, Ph.D., Simmons College Dissertation Director: Richard J. Cox, Ph.D., Advisor ii Copyright © by Donghee Sinn 2007 iii RECORDS AND THE UNDERSTANDING OF VIOLENT EVENTS: ARCHIVAL DOCUMENTATION, HISTORICAL PERCEPTION, AND THE NO GUN RI MASSACRE IN THE KOREAN WAR Donghee Sinn, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 The archival community has long shown an interest in documenting history, and it has been assumed that archival materials are one of the major sources of historical research. However, little is known about how much impact archival holdings actually have on historical research, what role they play in building public knowledge about a historical event and how they contribute to the process of recording history. The case of the No Gun Ri incident provides a good example of how archival materials play a role in historical discussions and a good opportunity to look at archival contributions.