Persian Connections Writings from the Exile Donald E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solomon's Legacy

Solomon’s Legacy Divided Kingdom Image from: www.lightstock.com Solomon’s Last Days -1 Kings 11 Image from: www.lightstock.com from: Image ➢ God raises up adversaries to Solomon. 1 Kings 11:14 14 Then the LORD raised up an adversary to Solomon, Hadad the Edomite; he was of the royal line in Edom. 1 Kings 11:23-25 23 God also raised up another adversary to him, Rezon the son of Eliada, who had fled from his lord Hadadezer king of Zobah. 1 Kings 11:23-25 24 He gathered men to himself and became leader of a marauding band, after David slew them of Zobah; and they went to Damascus and stayed there, and reigned in Damascus. 1 Kings 11:23-25 25 So he was an adversary to Israel all the days of Solomon, along with the evil that Hadad did; and he abhorred Israel and reigned over Aram. Solomon’s Last Days -1 Kings 11 Image from: www.lightstock.com from: Image ➢ God tells Jeroboam that he will be over 10 tribes. 1 Kings 11:26-28 26 Then Jeroboam the son of Nebat, an Ephraimite of Zeredah, Solomon’s servant, whose mother’s name was Zeruah, a widow, also rebelled against the king. 1 Kings 11:26-28 27 Now this was the reason why he rebelled against the king: Solomon built the Millo, and closed up the breach of the city of his father David. 1 Kings 11:26-28 28 Now the man Jeroboam was a valiant warrior, and when Solomon saw that the young man was industrious, he appointed him over all the forced labor of the house of Joseph. -

Wind Chasers Beware- Ecclesiastes 1

Wind Chasers Beware Eccleiase 1 Wisdom Literature While other civilizations shared in wisdom literature, the major difference is the Hebrew wisdom writings acknowledged one God, denying materialism and [the worship of many gods.] 2 Types of Wisdom Literature: Didactic (Practical/ Teaching) and Philosophical/Pessimistic (Critical/ Reflective/Questioning). The goal of wisdom is a proper relationship with YAHWEH. Wisdom Focus Didactic wisdom literature advocates the development of prudential habits, skills, and virtues. The aim is to develop moral character, personal success and happiness, safety, and well-being. Proverbs is an example of this type. Philosophical/Pessimistic wisdom literature delves deeper into issues facing mankind. It portrays the emptiness and folly of the search for insight and understanding apart from God. Job and Ecclesiastes are examples of this type. The words of the Preacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem. Ecclesiastes 1:1 Consider the Source Advice is only as good as the one giving it. Only 2 ways of learning something: Personal experience or 2nd hand. Solomon was the wisest man that ever lived. (See 1 Kings 3:11-14) Solomon saw one of Israel's wealthier periods. Ecclesiastes 1:2-6 “ Vanity of vanities,” says the Preacher, “Vanity of vanities! All is vanity.” What advantage does man have in all his work which he does under the sun? A generation goes and a generation comes, but the earth remains forever. Also, the sun rises and the sun sets; and hastening to its place it rises there again. Blowing toward the south, then turning toward the north, the wind continues swirling along; and on its circular courses the wind returns. -

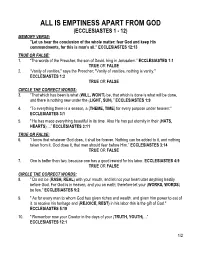

Is Emptiness Apart From

ALL IS EMPTINESS APART FROM GOD (ECCLESIASTES 1 - 12) MEMORY VERSE: "Let us hear the conclusion of the whole matter: fear God and keep His commandments, for this is man's all.” ECCLESIASTES 12:13 TRUE OR FALSE: 1. “The words of the Preacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem.” ECCLESIASTES 1:1 TRUE OR FALSE 2. “Vanity of vanities," says the Preacher; "Vanity of vanities, nothing is vanity." ECCLESIASTES 1:2 TRUE OR FALSE CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORDS: 3. “That which has been is what (WILL, WON’T) be, that which is done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the (LIGHT, SUN)." ECCLESIASTES 1:9 4. "To everything there is a season, a (THEME, TIME) for every purpose under heaven:" ECCLESIASTES 3:1 5. " He has made everything beautiful in its time. Also He has put eternity in their (HATS, HEARTS) ...” ECCLESIASTES 3:11 TRUE OR FALSE: 6. “I know that whatever God does, it shall be forever. Nothing can be added to it, and nothing taken from it. God does it, that men should fear before Him.” ECCLESIASTES 3:14 TRUE OR FALSE 7. One is better than two, because one has a good reward for his labor. ECCLESIASTES 4:9 TRUE OR FALSE CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORDS: 8. " Do not be (RASH, REAL) with your mouth, and let not your heart utter anything hastily before God. For God is in heaven, and you on earth; therefore let your (WORKS, WORDS) be few." ECCLESIASTES 5:2 9. " As for every man to whom God has given riches and wealth, and given him power to eat of it, to receive his heritage and (REJOICE, REST) in his labor-this is the gift of God." ECCLESIASTES 5:19 10. -

HEPTADIC VERBAL PATTERNS in the SOLOMON NARRATIVE of 1 KINGS 1–11 John A

HEPTADIC VERBAL PATTERNS IN THE SOLOMON NARRATIVE OF 1 KINGS 1–11 John A. Davies Summary The narrative in 1 Kings 1–11 makes use of the literary device of sevenfold lists of items and sevenfold recurrences of Hebrew words and phrases. These heptadic patterns may contribute to the cohesion and sense of completeness of both the constituent pericopes and the narrative as a whole, enhancing the readerly experience. They may also serve to reinforce the creational symbolism of the Solomon narrative and in particular that of the description of the temple and its dedication. 1. Introduction One of the features of Hebrew narrative that deserves closer attention is the use (consciously or subconsciously) of numeric patterning at various levels. In narratives, there is, for example, frequently a threefold sequence, the so-called ‘Rule of Three’1 (Samuel’s three divine calls: 1 Samuel 3:8; three pourings of water into Elijah’s altar trench: 1 Kings 18:34; three successive companies of troops sent to Elijah: 2 Kings 1:13), or tens (ten divine speech acts in Genesis 1; ten generations from Adam to Noah, and from Noah to Abram; ten toledot [‘family accounts’] in Genesis). One of the numbers long recognised as holding a particular fascination for the biblical writers (and in this they were not alone in the ancient world) is the number seven. Seven 1 Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folktale (rev. edn; Austin: University of Texas Press, 1968; tr. from Russian, 1928): 74; Christopher Booker, The Seven Basic Plots of Literature: Why We Tell Stories (London: Continuum, 2004): 229-35; Richard D. -

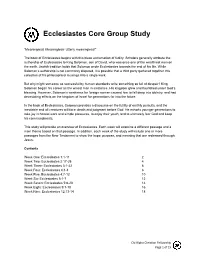

Ecclesiastes Core Group Study

Ecclesiastes Core Group Study “Meaningless! Meaningless! Utterly meaningless!” The book of Ecclesiastes begins with this bleak exclamation of futility. Scholars generally attribute the authorship of Ecclesiastes to King Solomon, son of David, who was once one of the wealthiest men on the earth. Jewish tradition holds that Solomon wrote Ecclesiastes towards the end of his life. While Solomon’s authorship is not commonly disputed, it is possible that a third party gathered together this collection of his philosophical musings into a single work. But why might someone so successful by human standards write something so full of despair? King Solomon began his career as the wisest man in existence. His kingdom grew and flourished under God’s blessing. However, Solomon’s weakness for foreign women caused him to fall deep into idolatry, and had devastating effects on the kingdom of Israel for generations far into the future. In the book of Ecclesiastes, Solomon provides a discourse on the futility of earthly pursuits, and the inevitable end all creatures will face: death and judgment before God. He exhorts younger generations to take joy in honest work and simple pleasures, to enjoy their youth, and to ultimately fear God and keep his commandments. This study will provide an overview of Ecclesiastes. Each week will examine a different passage and a main theme based on that passage. In addition, each week of the study will include one or more passages from the New Testament to show the hope, purpose, and meaning that are redeemed through Jesus. Contents Week One: Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 2 Week Two: Ecclesiastes 2:17-26 4 Week Three: Ecclesiastes 3:1-22 6 Week Four: Ecclesiastes 4:1-3 8 Week Five: Ecclesiastes 4:7-12 10 Week Six: Ecclesiastes 5:1-7 12 Week Seven: Ecclesiastes 5:8-20 14 Week Eight: Ecclesiastes 9:1-10 16 Week Nine: Ecclesiastes 12:13-14 18 Chi Alpha Christian Fellowship Page 1 of 19 Week One: Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 Worship Idea: Open in prayer, then sing some worship songs Opening Questions: 1. -

Ezekiel 14:9 Ezekiel Speaks of Those Who Abuse Their Prophetic Office

1 Ted Kirnbauer God Deceives the Prophets In Ezekiel 14:9 Ezekiel speaks of those who abuse their prophetic office. There he states that the false prophets speak deceptive words because God has deceived them. This of course generates a lot of questions: If God deceives people, how can He be Holy? How do we know that the gospel isn’t a deception of God as well? How can people be responsible for believing a deception if God is the one deceiving them? Answers to these questions would take volumes to explore, but hopefully, the following work by DA Carson and the comments that follow will shed a little light on the subject. Excurses - Sovereignty and Human Responsibility The sovereignty of God and human responsibility is not an easy concept with a simple solution. D.A. Carson does a good job at explaining the relationship between the two. The following comments are taken from A Call To Spiritual Reformation under the chapter entitled “A Sovereign and Personal God.” He says: I shall begin by articulating two truths, both of which are demonstrably taught or exemplified again and again in the Bible: 1. God is absolutely sovereign, but his sovereignty never functions in Scripture to reduce human responsibility. 2. Human beings are responsible creatures – that is, they choose, they believe, they disobey, they respond, and there is moral significance in their choices; but human responsibility never functions in Scripture to diminish God's sovereignty or to make God absolutely contingent. My argument is that both propositions are taught and exemplified in the Bible. -

The Relationship Between Targum Song of Songs and Midrash Rabbah Song of Songs

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TARGUM SONG OF SONGS AND MIDRASH RABBAH SONG OF SONGS Volume I of II A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2010 PENELOPE ROBIN JUNKERMANN SCHOOL OF ARTS, HISTORIES, AND CULTURES TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME ONE TITLE PAGE ............................................................................................................ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................. 2 ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................. 6 DECLARATION ........................................................................................................ 7 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ....................................................................................... 8 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DEDICATION ............................................................... 9 CHAPTER ONE : INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 11 1.1 The Research Question: Targum Song and Song Rabbah ......................... 11 1.2 The Traditional View of the Relationship of Targum and Midrash ........... 11 1.2.1 Targum Depends on Midrash .............................................................. 11 1.2.2 Reasons for Postulating Dependency .................................................. 14 1.2.2.1 Ambivalence of Rabbinic Sources Towards Bible Translation .... 14 1.2.2.2 The Traditional -

Righteousness and Wickedness in Ecclesiastes 7:15-18

Scholars Crossing SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations 1985 Righteousness and Wickedness in Ecclesiastes 7:15-18 Wayne Brindle Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs Recommended Citation Brindle, Wayne, "Righteousness and Wickedness in Ecclesiastes 7:15-18" (1985). SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations. 105. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs/105 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 242 DANIEL A. AUGSBURGER Andrews University Seminary Studies, Autumn 1985, Vol. 23, No.3, 243-257. Copyright rg 1985 by Andrews University Press. effort was not vain, however, for it was one of the greatest incentives for the spiritual descendants of Zwingli to love the Scripture and to be diligent students of its pages. It was also the root of one of the greatest privileges of modern man in many of the Christian lands RIGHTEOUSNESS AND WICKEDNESS IN religious freedom. ECCLESIASTES 7:15-18 WA YNE A. BRINDLE B. R. Lakin School of Religion Liberty University Lynchburg, Virginia 24506 Good and evil, righteousness and wickedness, virtue and vice-these are common subjects in the Scriptures. The poetical books, especially, are much concerned with the acts of righteous and unrighteous persons. Qoheleth, in Ecclesiastes, declares that "there is nothing better ... than to rejoice and to do good in one's lifetime" (3: 12, NASB). In fact, he concludes the book with the warning that "God will bring every act to judgment, everything which is hidden, whether it is good or evil" (12:14). -

Ecclesiastes “Life Under the Sun”

Ecclesiastes “Life Under the Sun” I. Introduction to Ecclesiastes A. Ecclesiastes is the 21st book of the Old Testament. It contains 12 chapters, 222 verses, and 5,584 words. B. Ecclesiastes gets its title from the opening verse where the author calls himself ‘the Preacher”. 1. The Septuagint (the translation of the Hebrew into the common language of the day, Greek) translated this word, Preacher, as Ecclesiastes and thus e titled the book. a. Ecclesiastes means Preacher; the Hebrew word “Koheleth” carries the menaing of preacher, teacher, or debater. b. The idea is that the message of Ecclesiastes is to be heralded throughout the world today. C. Ecclesiastes was written by Solomon. 1. Jewish tradition states Solomon wrote three books of the Bible: a. Song of Solomon, in his youth b. Proverbs, in his middle age years c. Ecclesiastes, when he was old 2. Solomon’s authorship had been accepted as authentic, until, in the past few hundred years, the “higher critics” have attempted to place the book much later and attribute it to someone pretending to be Solomon. a. Their reasoning has to do with a few words they believe to be of a much later usage than Solomon’s time. b. The internal evidence, however, strongly supports Solomon as the author. i. Ecc. 1:1 He calls himself the son of David and King of Jerusalem ii. Ecc. 1:12 Claims to be King over Israel in Jerusalem” iii. Only Solomon ruled over all Israel from Jerusalem; after his reign, civil war split the nation. Those in Jerusalem ruled over Judah. -

Ezekiel Week 9 Idolaters and Jerusalem Condemned Chapters 14-15

Ezekiel Week 9 Idolaters and Jerusalem Condemned Chapters 14-15 Idolatrous Elders Condemned (14:1-11) The elders served as the authorities for the exiles. They came to Ezekiel as supplicants seeking counsel and an oracle. The gesture of sitting before him (at his feet) indicates his role as teacher and spokesperson for God. There is some question whether they sincerely accepted his authority or were simply curious about what he could offer as a word of God.1 Ezekiel had by now received accreditation through the fulfillment of his earlier oracles, and it was with not unreasonable expectation of a positive word for the future that the elders came. However, they were to be disappointed. There was no automatic word of salvation for them. The era of promise was not to dawn as an inalienable right of all members of God’s people. 2 The Hebrew word for idols used here, gillulim, appears only in the plural in the ot and always in reference to idols. The biblical use is intentionally insulting and disparaging because gillulim is based on the word gel, meaning “dung” (see 4:12; Job 20:7). The whole phrase, gilluleihem al-libbam, can be taken literally or metaphorically. The elders might be literally guilty by wearing some sort of magical amulet around their necks, or they may simply be guilty of devotion to other gods. Wearing protective amulets was a common practice among the Babylonians. They wore amulets to protect against demons, ensure a safe pregnancy and birth, facilitate romantic attraction, or protect themselves from destruction and disease.3 The elders in exile are tainted with the same fundamental sin as those left behind in Judah: internal idolatry. -

Septuagint Vs. Masoretic Text and Translations of the Old Testament

#2 The Bible: Origin & Transmission November 30, 2014 Septuagint vs. Masoretic Text and Translations of the Old Testament The Septuagint (Greek translation of the Old Testament) captured the Original Hebrew Text before Mistakes crept in. Psalm 119:89 Forever, O LORD, Your word is settled in heaven. 2 Timothy 3:16 All Scripture is inspired breathed by God 2 Peter 1:20-21 No prophecy of Scripture is a matter of one's own interpretation, for no prophecy was ever made by an act of human will, but men moved by the but men carried along by Holy Spirit spoke from God. Daniel 8:5 While I was observing, behold, a male goat was coming from the west over the surface of the whole earth without touching the ground 1 Kings 4:26 Solomon had 40,000 stalls of horses for his chariots, and 12,000 horsemen. 2 Chronicles 9:25 Now Solomon had 4,000 stalls for horses and chariots and 12,000 horsemen, 1 Kings 5:15-16 Now Solomon had 70,000 transporters, and 80,000 hewers of stone in the mountains, besides Solomon's 3,300 chief deputies who were over the project and who ruled over the people who were doing the work. 2 Chronicles 2:18 He appointed 70,000 of them to carry loads and 80,000 to quarry stones in the mountains and 3,600 supervisors . Psalm 22:14 (Masoretic) I am poured out like water, and all my bones are out of joint; My heart is like wax; it is melted within me. -

Ecclesiastes – “It’S ______About _____”

“DISCOVERING THE UNREAD BESTSELLER” Week 18: Sunday, March 25, 2012 ECCLESIASTES – “IT’S ______ ABOUT _____” BACKGROUND & TITLE The Hebrew title, “___________” is a rare word found only in the Book of Ecclesiastes. It comes from a word meaning - “____________”; in fact, it’s talking about a “_________” or “_________”. The Septuagint used the Greek word “__________” as its title for the Book. Derived from the word “ekklesia” (meaning “assembly, congregation or church”) the title again (in the Greek) can simply be taken to mean - “_________/_________”. AUTHORSHIP It is commonly believed and accepted that _________authored this Book. Within the Book, the author refers to himself as “the son of ______” (Ecclesiastes 1:1) and then later on (in Ecclesiastes 1:12) as “____ over _____ in Jerusalem”. Solomon’s extensive wisdom; his accomplishments, and his immense wealth (all of which were God-given) give further credence to his work. Outside the Book, _______ tradition also points to Solomon as author, but it also suggests that the text may have undergone some later editing by _______ or possibly ____. SNAPSHOT OF THE BOOK The Book of Ecclesiastes describes Solomon’s ______ for meaning, purpose and satisfaction in life. The Book divides into three different sections - (1) the _____ that _______ is ___________ - (Ecclesiastes 1:1-11); (2) the ______ that everything is meaningless (Ecclesiastes 1:12-6:12); and, (3) the ______ or direction on how we should be living in a world filled with ______ pursuits and meaninglessness (Ecclesiastes 7:1-12:14). That last section is important because the Preacher/Teacher ultimately sees the emptiness and futility of all the stuff people typically strive for _____ from God – p______ – p_______ – p________ - and p________.