The Punished and the Lamenting Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jesus Said in Luke 4:18

Deliverance Jesus said in Luke 4:18 "The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he hath anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor; he hath sent me to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and recovery of sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised." Sharing the same anointing by His Holy Spirit, I realized that we also have the same commission. Although I preached the Gospel, I laid hands on the sick and healed the brokenhearted; I hadn't moved out into deliverance ministry - but that changed after a mission trip to Europe! I know that it is no coincidence that while ministering in Vienna, I was trained by one of the best in the field of deliverance. It was truly awesome to see the change in peoples' continence and lives after being set free from demonic oppression. Sister Pastor Irene and I stepped out in this new phase of ministry in 1999. We are filled with such compassion to "set the captives free" when we see the control the enemy exercises over some peoples' lives. Many are oppressed by spirits of fear, bondage, and rejection, that had come in during childhood (through no fault of their own), or resulting from abuse by an family member. Jesus said in Luke 10:19: "Behold, I give unto you power to tread on serpents and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy: and nothing shall by any means hurt you." He also stated in Mark 16:17 "And these signs shall follow them that believe: in my name shall they cast out devils..." There are seventeen "Strongmen" identified in the bible. -

Royal Matrimony: the Theme of Kingship in the Book of Song Of

1 REFORMED THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY CHARLOTTE ‘ROYAL MATRIMONY: THE THEME OF KINGSHIP IN THE BOOK OF SONG OF SONGS AS AN APOLOGETIC TO SOLOMON’ SUBMITTED TO DR. RICHARD BELCHER, JR. IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF OT512- POETS (1st YEAR) BY DÓNAL WALSH, MAY 15, 2018 2 The Song of Songs is the subject of no little debate among Bible scholars today. Commentators are generally united in saying that it is a beautiful redemptive poem about love, but the consensus ends there.1 Debates proliferate over its authorship, date, use of imagery, role and number of characters in the book and overall purpose. The interpreter is left to sift through the perplexing and multi-faceted perspectives on the book. This essay hopes to clear up some of this fog by focusing on one major theme: royal kingship. I propose that the Song is a redemptive love poem which also functions as an apologetic work written with Solomon in mind. It is a defense of faithful, monogamous marital love both to Israel and, especially, to Solomon. To establish this premise, I will discuss a proposed apologetic model that is used in the Song, how this relates to the royal theme, the implications of this apologetic reading on how we date the book, and lastly discern its purpose, author, and how this apologetic speaks to us pastorally and Christologically today. An Apologetic Model A big question, as we investigate this royal theme, is how Solomon can be portrayed in both a positive and negative light. Some commentators see him as a manipulative, domineering king who wants to seduce the Shulamite girl into his harem,2 while others take him to be the author of the book, and the ideal king and lover.3 Still others see him in a negative light, but whose royal traits are appropriated positively by the woman in praise of 1 Athalya Brenner, The Song of Songs, Old Testament Guides (Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1989), 63–64; Raymond B. -

The Song of Songs Celebrates God's Kind of Love1

The Song of Songs Celebrates God’s Kind of Love1 Aída Besançon Spencer Introduction fits all the data.12 Further, who is speaking is identified by the use of imagery. Imagery by or about Solomon tends to be more ur- Romance novels are popular, especially among women. Romance ban, financial, militaristic, and related to travel. Also, the ancient fiction sells more than inspirational, mystery, science fiction, Masorite scribes (and probably those earlier) used Hebrew letters fantasy, or classic literary fiction. It had the largest share of the to indicate paragraph markings in the Hebrew Bible. These may United States consumer market in 2012. What are the two ba- even have been in the earliest original biblical scrolls.13 In the sic elements in every romance novel, according to the Romance Song of Songs, the Hebrew letter samek (or the sethumai) tends to Writers of America? “A central love story and an emotionally indicate a change of perspective or locale, while the Hebrew letter satisfying and optimistic ending. In a romance, the lovers pē (pethuma) indicates the beginning of the final conclusion at who risk and struggle for each other and their relationship are 8:11. In addition, in Hebrew, some pronouns are either masculine rewarded with emotional justice and unconditional love.” More or feminine and help readers in discovering if an individual man than ninety percent of the market is comprised of women.2 or a woman is addressed. The two men who court the heroine are The Bible contains numerous romances, but the Song of Songs presented in the first eight verses of chapter one. -

The Relationship Between Targum Song of Songs and Midrash Rabbah Song of Songs

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TARGUM SONG OF SONGS AND MIDRASH RABBAH SONG OF SONGS Volume I of II A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2010 PENELOPE ROBIN JUNKERMANN SCHOOL OF ARTS, HISTORIES, AND CULTURES TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME ONE TITLE PAGE ............................................................................................................ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................. 2 ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................. 6 DECLARATION ........................................................................................................ 7 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ....................................................................................... 8 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DEDICATION ............................................................... 9 CHAPTER ONE : INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 11 1.1 The Research Question: Targum Song and Song Rabbah ......................... 11 1.2 The Traditional View of the Relationship of Targum and Midrash ........... 11 1.2.1 Targum Depends on Midrash .............................................................. 11 1.2.2 Reasons for Postulating Dependency .................................................. 14 1.2.2.1 Ambivalence of Rabbinic Sources Towards Bible Translation .... 14 1.2.2.2 The Traditional -

Lamentations 1-5 Pastor Bob Singer 03/24/2019

Fact Sheet for “Doom” Lamentations 1-5 Pastor Bob Singer 03/24/2019 We have come to the book of Lamentations. The title of this book… “Lamentations”… aptly describes its content. These five chapters are filled with gut-wrenching pain and anguish over the destruction of Jerusalem and what the Jewish people had experienced and were experiencing. It’s not an easy book to wrap your heart around, but there is a small island of verses right in the middle that have long been a focus of encouragement for God’s people. But let’s begin with a little of the background of this book. 1. It is generally assumed that Jeremiah wrote it, even though its author is not identified. It was written at the right time for Jeremiah to have authored it. And many of the themes found here are also found in the book of Jeremiah. 2. Each chapter is a highly structured poem. The first four are acrostics based on the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet. Each stanza begins with the appropriate letter. Unfortunately, there is no way to show this in translations. This is why chapters 1,2 and 4 have 22 verses, and why chapter 3 has 66. Chapter 5 also has 22 verses, but it is not an acrostic. Here’s a run-down of their lives. 1. Famine was an every-day threat. The Babylonians had laid siege to the city for a year and a half. They cut off the supply of food for the city. And the famine grew ever worse. -

J. Paul Tanner, "The Message of the Song of Songs,"

J. Paul Tanner, “The Message of the Song of Songs,” Bibliotheca Sacra 154: 613 (1997): 142-161. The Message of the Song of Songs — J. Paul Tanner [J. Paul Tanner is Lecturer in Hebrew and Old Testament Studies, Singapore Bible College, Singapore.] Bible students have long recognized that the Song of Songs is one of the most enigmatic books of the entire Bible. Compounding the problem are the erotic imagery and abundance of figurative language, characteristics that led to the allegorical interpretation of the Song that held sway for so much of church history. Though scholarly opinion has shifted from this view, there is still no consensus of opinion to replace the allegorical interpretation. In a previous article this writer surveyed a variety of views and suggested that the literal-didactic approach is better suited for a literal-grammatical-contextual hermeneutic.1 The literal-didactic view takes the book in an essentially literal way, describing the emotional and physical relationship between King Solomon and his Shulammite bride, while at the same time recognizing that there is a moral lesson to be gained that goes beyond the experience of physical consummation between the man and the woman. Laurin takes this approach in suggesting that the didactic lesson lies in the realm of fidelity and exclusiveness within the male-female relationship.2 This article suggests a fresh interpretation of the book along the lines of the literal-didactic approach. (This is a fresh interpretation only in the sense of making refinements on the trend established by Laurin.) Yet the suggested alternative yields a distinctive way in which the message of the book comes across and Solomon himself is viewed. -

The Song of Songs Seder: a Night of Sacred Sexuality by Rabbi Robert Teixeira, LCSW

The Song of Songs Seder: A Night of Sacred Sexuality By Rabbi Robert Teixeira, LCSW Many fault lines cut through the human family. The Sex-Is-Holy - Sex-Is-Dirty divide, which inflicts untold suffering on millions, is one of the widest and oldest. We find evidence of this divide in every faith tradition, including Judaism, where we encounter it numerous times in the Talmud, in reference to the Song of Songs, for example. This work, which revolves around the play of two Lovers, is by far the most erotic book in the Bible. According to the Talmud, the Song of Songs was set aside to be buried because of its sensual content (Avot De-Rabbi Nathan 1:4). These verses were singled out as particularly offensive: I am my beloved’s, and his desire is for me. Come, my beloved, let us go into the open; let us lodge among the henna shrubs. Let us go early to the vineyards; let us see if the vine has flowered, if its blossoms have opened, if the pomegranates are in bloom. There I will give my love to you.” (Song of Songs 7:11-13) At length, the rabbis debated whether to include the Song of Songs in the Bible. In their deliberations, they used the curious phrase “renders unclean the hands.” Holy books, in their view, were essentially “too hot to handle” on account of their intrinsic holiness. Handling them, then, renders unclean the hands, that is, makes one more or less untouchable, until specific rituals of purification are carried out. -

Life Goes On; Justice Will Come Lamentations 4

Life Goes On; Justice Will Come Lamentations 4 No matter how much faith a believer has, no matter how much hope they can muster, faith and hope do not make reality disappear, nor do they undermine its seriousness. Sometimes God delivers with a miracle. Other times believers are called to persevere in faith and witness, trusting God as he fulfils his purposes. Faith and hope notwithstanding, the reality remained: Judah was under foreign occupation. Jerusalem had been ravaged, devastated and traumatised. Restoration and recompense lay in the future. In Lamentations 3:64–66, the lens zooms out to focus for a moment on the future that is promised. But the focus cannot stay there, for life goes on. And in Lamentations 4 we are returned to Jerusalem’s present reality as the lens zooms back in to focus on the ground upon which the people presently stand. This is what survivors do – they to cling to future hope while pressing on through present trials. Discuss: Have you ever felt guilty or ashamed, like a spiritual failure, because your faith in God and hope in the future did not dispel your suffering or reduce your grief? What pressure did that put on you? How can we best help those who suffer and grieve? § After the sermon of Lamentations 3, Lamentations 4 returns to the scene of Lamentations 1 and 2 and reinforces the truth that God takes the reality of pain and suffering seriously. Hardship and suffering do not come to an end with the emergence of hope; it is not an instant fix. -

2019 0304 Quiet Waters.Pub

Friday, March 8, 2019 Trusting Isaiah 2-3 March 4 - 9, 2019 Stop trusting in man, who has but a breath in his nostrils. Of what account is he? Isaiah 2:22 The day of the LORD is coming. The LORD Almighty has a day in store (2:12). God is supreme over all things for all time. He is the Majestic Ruler of all there is. Yet mankind refuses to trust Him! Isaiah speaks of the Day that is coming and calls on the people of Israel to stop trusting in man and in the idols that man has formed and shaped. God brought His people out of Egypt so that they could worship Him and He brought them to the land of Canaan with the command to remove all false gods so they would not be led astray. But they were swept away by the worship of man and what man had made. Over and over in the Bible I see God speaking this same command. Stop trusting in that which is untrustworthy. Yet I see all too often that I trust what I physically see—even when I know it will fail—rather than to trust in God. It causes disappointment in my life and in others when I trust them to do that which only God can do. Dear God, I trust You. I really do. Yet so many times I find myself swept away into placing my trust in other things. Then I get worried and frustrated and distanced from You. Please remind me often of Your trustworthiness. -

Scrolls of Love Ruth and the Song of Songs Scrolls of Love

Edited by Peter S. Hawkins and Lesleigh Cushing Stahlberg Scrolls of Love ruth and the song of songs Scrolls of Love ................. 16151$ $$FM 10-13-06 10:48:57 PS PAGE i ................. 16151$ $$FM 10-13-06 10:48:57 PS PAGE ii Scrolls of Love reading ruth and the song of songs Edited by Peter S. Hawkins and Lesleigh Cushing Stahlberg FORDHAM UNIVERSITY PRESS New York / 2006 ................. 16151$ $$FM 10-13-06 10:49:01 PS PAGE iii Copyright ᭧ 2006 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, me- chanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Scrolls of love : reading Ruth and the Song of songs / edited by Peter S. Hawkins and Lesleigh Cushing Stahlberg.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8232-2571-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8232-2571-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8232-2526-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8232-2526-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Bible. O.T. Ruth—Criticism interpretation, etc. 2. Bible. O.T. Song of Solomon—Criticism, interpretation, etc. I. Hawkins, Peter S. II. Stahlberg, Lesleigh Cushing. BS1315.52.S37 2006 222Ј.3506—dc22 2006029474 Printed in the United States of America 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1 First edition ................. 16151$ $$FM 10-13-06 10:49:01 PS PAGE iv For John Clayton (1943–2003), mentor and friend ................ -

Lamentations Bible Study Guide

GREAT IS HIS FAITHFULNESS: a study of LAMENTATIONS PERSONAL STUDY GUIDE SUNDAY SCHOOL | 7 WEEKS PERSONAL STUDY GUIDE GREAT IS HIS FAITHFULNESS: a study of LAMENTATIONS PERSONAL STUDY GUIDE SUNDAY SCHOOL | 7 WEEKS Dr. Daniel Hinton, author TABLE OF CONTENTS a letter from Steven W. Smith, PhD Great is Your Faithfulness. Dear Family, It may seem a little strange to study a song book of laments. This is perhaps among the darkest books in the Bible. And for this reason, it is so right. So appropriate. Our world, our days, and our own hearts are filled with dark places and dark times. One of the most important things to remember about the Bible is that it is “situational”. Meaning, God wrote his perfect word from people who were in situations, and into the lives of people in situations. Some good. Some bad. And some dark. There is not a dark night of the soul that is not explored in the word of God. Perhaps the most tragic of all the verses in Lamentations is the first verse: “How lonely sits the city…” The city of Jerusalem was one of the most vibrant places one could ever imagine. Breath taking, stunning. Under the reign of her most dominant monarchs, she was untouchable. And yet while her geography did not changed her majesty did. She is on the hill, and is decimated. She is the city that cannot be hidden, even though she would want to me. How lonely. Into that loneliness the prophet Jeremiah weeps. He mourns for the loss of innocence, the mourns the loss of blessing, He mourns the loss of victory. -

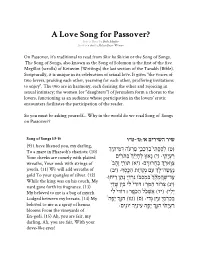

A Love Song for Passover? Source Sheet by Beth Schafer Based on a Sheet by Melissa Buyer-Witman

A Love Song for Passover? Source Sheet by Beth Schafer Based on a sheet by Melissa Buyer-Witman On Passover, it's traditional to read from Shir ha Shirim or the Song of Songs. The Song of Songs, also known as the Song of Solomon is the first of the five Megillot (scrolls) of Ketuvim (Writings) the last section of the Tanakh (Bible). Scripturally, it is unique in its celebration of sexual love. It gives "the voices of two lovers, praising each other, yearning for each other, proffering invitations to enjoy". The two are in harmony, each desiring the other and rejoicing in sexual intimacy; the women (or "daughters") of Jerusalem form a chorus to the lovers, functioning as an audience whose participation in the lovers' erotic encounters facilitates the participation of the reader. So you must be asking yourself... Why in the world do we read Song of Songs on Passover?? שיר השירים א׳:ט׳-ט״ו Song of Songs 1:9-15 ֙ ֣ ֔ ֖ ְ ,I have likened you, my darling (9) (ט) ְל ֻס ָס ִתי ְּב ִר ְכ ֵבי ַפ ְרעֹה ִ ּד ִּמי ִתיך (To a mare in Pharaoh’s chariots: (10 ַר ְעיָ ִ ֽתי׃ (י) ָנא ֤ווּ ְל ָח ַ֙י ִי ְ֙ך ַּב ּתֹ ִ ֔רים Your cheeks are comely with plaited ַצ ָוּא ֵ ֖ר ְך ַּב ֲחרוּ ִזֽים׃ (יא) ּת ֹו ֵ ֤רי ָז ָה ֙ב wreaths, Your neck with strings of ַנ ֲע ֶׂשה־ ָּ֔ל ְך ִ ֖עם ְנ ֻק ּ֥ד ֹות ַה ָּכֽ ֶסף׃ (יב) jewels. (11) We will add wreaths of ַעד־ ׁ ֶ֤ש ַה ֶּ֙מ ֶל ְ֙ך ִּב ְמ ִס ּ֔ב ֹו ִנ ְר ִ ּ֖די ָנ ַ ֥תן ֵריחֽ ֹו׃ (gold To your spangles of silver.