Einführung Jonathan Magonet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Emptiness Apart From

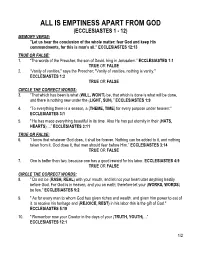

ALL IS EMPTINESS APART FROM GOD (ECCLESIASTES 1 - 12) MEMORY VERSE: "Let us hear the conclusion of the whole matter: fear God and keep His commandments, for this is man's all.” ECCLESIASTES 12:13 TRUE OR FALSE: 1. “The words of the Preacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem.” ECCLESIASTES 1:1 TRUE OR FALSE 2. “Vanity of vanities," says the Preacher; "Vanity of vanities, nothing is vanity." ECCLESIASTES 1:2 TRUE OR FALSE CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORDS: 3. “That which has been is what (WILL, WON’T) be, that which is done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the (LIGHT, SUN)." ECCLESIASTES 1:9 4. "To everything there is a season, a (THEME, TIME) for every purpose under heaven:" ECCLESIASTES 3:1 5. " He has made everything beautiful in its time. Also He has put eternity in their (HATS, HEARTS) ...” ECCLESIASTES 3:11 TRUE OR FALSE: 6. “I know that whatever God does, it shall be forever. Nothing can be added to it, and nothing taken from it. God does it, that men should fear before Him.” ECCLESIASTES 3:14 TRUE OR FALSE 7. One is better than two, because one has a good reward for his labor. ECCLESIASTES 4:9 TRUE OR FALSE CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORDS: 8. " Do not be (RASH, REAL) with your mouth, and let not your heart utter anything hastily before God. For God is in heaven, and you on earth; therefore let your (WORKS, WORDS) be few." ECCLESIASTES 5:2 9. " As for every man to whom God has given riches and wealth, and given him power to eat of it, to receive his heritage and (REJOICE, REST) in his labor-this is the gift of God." ECCLESIASTES 5:19 10. -

Ecclesiastes Song of Solomon

Notes & Outlines ECCLESIASTES SONG OF SOLOMON Dr. J. Vernon McGee ECCLESIASTES WRITER: Solomon. The book is the “dramatic autobiography of his life when he got away from God.” TITLE: Ecclesiastes means “preacher” or “philosopher.” PURPOSE: The purpose of any book of the Bible is important to the correct understanding of it; this is no more evident than here. Human philosophy, apart from God, must inevitably reach the conclusions in this book; therefore, there are many statements which seem to contra- dict the remainder of Scripture. It almost frightens us to know that this book has been the favorite of atheists, and they (e.g., Volney and Voltaire) have quoted from it profusely. Man has tried to be happy without God, and this book shows the absurdity of the attempt. Solomon, the wisest of men, tried every field of endeavor and pleasure known to man; his conclusion was, “All is vanity.” God showed Job, a righteous man, that he was a sinner in God’s sight. In Ecclesiastes God showed Solomon, the wisest man, that he was a fool in God’s sight. ESTIMATIONS: In Ecclesiastes, we learn that without Christ we can- not be satisfied, even if we possess the whole world — the heart is too large for the object. In the Song of Solomon, we learn that if we turn from the world and set our affections on Christ, we cannot fathom the infinite preciousness of His love — the Object is too large for the heart. Dr. A. T. Pierson said, “There is a danger in pressing the words in the Bible into a positive announcement of scientific fact, so marvelous are some of these correspondencies. -

Ecclesiastes – “It’S ______About _____”

“DISCOVERING THE UNREAD BESTSELLER” Week 18: Sunday, March 25, 2012 ECCLESIASTES – “IT’S ______ ABOUT _____” BACKGROUND & TITLE The Hebrew title, “___________” is a rare word found only in the Book of Ecclesiastes. It comes from a word meaning - “____________”; in fact, it’s talking about a “_________” or “_________”. The Septuagint used the Greek word “__________” as its title for the Book. Derived from the word “ekklesia” (meaning “assembly, congregation or church”) the title again (in the Greek) can simply be taken to mean - “_________/_________”. AUTHORSHIP It is commonly believed and accepted that _________authored this Book. Within the Book, the author refers to himself as “the son of ______” (Ecclesiastes 1:1) and then later on (in Ecclesiastes 1:12) as “____ over _____ in Jerusalem”. Solomon’s extensive wisdom; his accomplishments, and his immense wealth (all of which were God-given) give further credence to his work. Outside the Book, _______ tradition also points to Solomon as author, but it also suggests that the text may have undergone some later editing by _______ or possibly ____. SNAPSHOT OF THE BOOK The Book of Ecclesiastes describes Solomon’s ______ for meaning, purpose and satisfaction in life. The Book divides into three different sections - (1) the _____ that _______ is ___________ - (Ecclesiastes 1:1-11); (2) the ______ that everything is meaningless (Ecclesiastes 1:12-6:12); and, (3) the ______ or direction on how we should be living in a world filled with ______ pursuits and meaninglessness (Ecclesiastes 7:1-12:14). That last section is important because the Preacher/Teacher ultimately sees the emptiness and futility of all the stuff people typically strive for _____ from God – p______ – p_______ – p________ - and p________. -

The Punished and the Lamenting Body

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 8 Original Research The punished and the lamenting body Author: The 5 lamentations, when read as a single biblical book, outline several interacting bodies in a 1 Pieter van der Zwan similar way that dotted lines present the silhouettes and aspects of a total picture. Each also Affiliation: represents action, building into a plot that can be interpreted psychoanalytically to render its 1Department of Old depth and colour content. In addition, by focusing on the body and its sensations, this study Testament, University of can facilitate the visceral experience of the suffering of collective and individual bodies by the South Africa, South Africa recipient. Corresponding author: Pieter van der Zwan, [email protected] Introduction Dates: This study is dedicated to my doctoral supervisor, Prof. Eben Scheffler, whom I met for the first Received: 11 May 2018 time in 1993 at my final oral examination for the BD degree before we started our long journey Accepted: 15 Sept. 2018 about the celebration of the body in the book of Song of Songs. During these 25 years, we have Published: 26 Feb. 2019 become deep friends where conflict can be accommodated, just as it is in the collection of How to cite this article: testimonies about crisis and traumatic experiences of God, testimonies that have inspired us both, Van der Zwan, P., 2019, ‘The also in our ageing bodies. One particular expression of this struggle Prof. Scheffler once verbalised punished and the lamenting as being imprisoned by the body, when I accidentally made him walk in the wrong direction at an body’, HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies airport some years ago. -

The Song of Songs Seder: a Night of Sacred Sexuality by Rabbi Robert Teixeira, LCSW

The Song of Songs Seder: A Night of Sacred Sexuality By Rabbi Robert Teixeira, LCSW Many fault lines cut through the human family. The Sex-Is-Holy - Sex-Is-Dirty divide, which inflicts untold suffering on millions, is one of the widest and oldest. We find evidence of this divide in every faith tradition, including Judaism, where we encounter it numerous times in the Talmud, in reference to the Song of Songs, for example. This work, which revolves around the play of two Lovers, is by far the most erotic book in the Bible. According to the Talmud, the Song of Songs was set aside to be buried because of its sensual content (Avot De-Rabbi Nathan 1:4). These verses were singled out as particularly offensive: I am my beloved’s, and his desire is for me. Come, my beloved, let us go into the open; let us lodge among the henna shrubs. Let us go early to the vineyards; let us see if the vine has flowered, if its blossoms have opened, if the pomegranates are in bloom. There I will give my love to you.” (Song of Songs 7:11-13) At length, the rabbis debated whether to include the Song of Songs in the Bible. In their deliberations, they used the curious phrase “renders unclean the hands.” Holy books, in their view, were essentially “too hot to handle” on account of their intrinsic holiness. Handling them, then, renders unclean the hands, that is, makes one more or less untouchable, until specific rituals of purification are carried out. -

Ecclesiastes: the Philippians of the Old Testament

Ecclesiastes: The Philippians of the Old Testament Bereans Adult Bible Fellowship Placerita Baptist Church 2010 by William D. Barrick, Th.D. Professor of OT, The Master’s Seminary Chapter 12 Life Under a Setting Sun In conclusion, the Preacher determines to fear God, obey God, and enjoy life (9:1–12:14) Continuing the book’s grand finale (11:9–12:7), Solomon transitions from the enjoyment of “seeing the sun” to the approach of death. Assuming temporal existence for mankind “under the sun,” “he broadens the range of his observation to include God, who is above the sun, and death, which is beyond the sun.”1 When the wise contemplate death, they find all aspirations to grandeur and gain exposed as illusory visions of their own arrogance. Brown says of such contemplation, that it “purges the soul of all futile striving and, paradoxically, anxiety. The eternal sleep of death serves as a wake-up call to live and welcome the serendipities of the present.”2 Just as the setting sun signals the end of a day, so aging signals the approach of the close of one’s life. Preparation for the end of life must begin even in youth. “Before” in verses 1, 2, and 6 sets up a time-oriented series of statements that favor understanding the text as a description of the time of death, rather than merely a depiction of the process of aging.3 The first seven verses of this chapter comprise one long sentence.4 If someone were to read it aloud as one sentence, he or she would be “‘out of breath’ by the end”5—a play on the key word hebel, which can also mean “breath,” as well as “vanity,” “futility,” or “fleeting.” However, the interpreter would be remiss to focus too much upon death in this section. -

Ecclesiastes 12 Do It Now As We Begin the Last Chapter of Ecclesiastes Let Me Remind You of the Four Major Points of the Last Tw

Ecclesiastes 12 Do It Now As we begin the last chapter of Ecclesiastes let me remind you of the four major points of the last two chapters: 1. Life is an adventure – live it by faith, 2. Life is a gift – enjoy it, 3. Life is a stewardship – live it for the glory of God and 4. Life is short – therefore serve God now. This is what the last chapter is all about, serve God, do it now, before it’s too late. We don’t serve God because He needs something from us. Acts 17 tells us that God is not served by our works as though he needed anything “since He gives to all life, breath and all things.”1 We serve God by loving Him and obeying Him and in return our lives are filled with His grace, power and love. Here in the last chapter of Ecclesiastes the call to serve God now is made specifically to young people. Someone has said that youth is for pleasure, middle age is for business and old age is for religion. That is a frightful delusion. We need to love and serve God now, for our own wellbeing, because tomorrow is never guaranteed. So let’s begin. Remember now your Creator in the days of your youth, Before the difficult days come, And the years draw near when you say, “I have no pleasure in them”: (Ecclesiastes 12:1) Remember your Creator. Think carefully about your Creator. Live in His presence daily. Seek to discover His greatness and glory now. -

![Commentary on Ecclesiastes 11:9-12:7, 13 [14] by L.G](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2509/commentary-on-ecclesiastes-11-9-12-7-13-14-by-l-g-1042509.webp)

Commentary on Ecclesiastes 11:9-12:7, 13 [14] by L.G

Commentary on Ecclesiastes 11:9-12:7, 13 [14] By L.G. Parkhurst, Jr. The International Bible Lesson (Uniform Sunday School Series) for Sunday, October 16, 2011, is from Ecclesiastes 11:9-12:7, 13. Five Questions for Discussion and Thinking Further follow the Bible Lesson Commentary below. Study Hints for Thinking Further, which are also available on the Bible Lesson Forum, will aid teachers in conducting class discussion. Ecclesiastes 11:9-12:7, 13 [14] (Ecclesiastes 11:9) Rejoice, young man, while you are young, and let your heart cheer you in the days of your youth. Follow the inclination of your heart and the desire of your eyes, but know that for all these things God will bring you into judgment. Solomon’s book tells young people to enjoy being young while they can, for they will soon be old. He also tells young people the choice before them. They can do what they want (set their own goals and follow their feelings) or they can “keep God’s commandments” (see Ecclesiastes 12:13). If they obey or disobey God when following their feelings or setting their own goals, then God will judge whether their choices and actions are right or wrong, good or evil (see Ecclesiastes 12:14). God will hold everyone accountable and responsible for their way of life. (Ecclesiastes 11:10) Banish anxiety from your mind, and put away pain from your body; for youth and the dawn of life are vanity. The “dawn of life” (meaning “infancy and childhood”) and youth are vanity or meaningless depending on what a child or youth plans to do and what actions they take. -

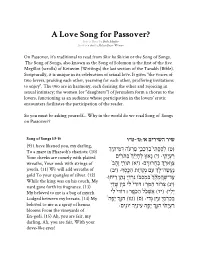

A Love Song for Passover? Source Sheet by Beth Schafer Based on a Sheet by Melissa Buyer-Witman

A Love Song for Passover? Source Sheet by Beth Schafer Based on a sheet by Melissa Buyer-Witman On Passover, it's traditional to read from Shir ha Shirim or the Song of Songs. The Song of Songs, also known as the Song of Solomon is the first of the five Megillot (scrolls) of Ketuvim (Writings) the last section of the Tanakh (Bible). Scripturally, it is unique in its celebration of sexual love. It gives "the voices of two lovers, praising each other, yearning for each other, proffering invitations to enjoy". The two are in harmony, each desiring the other and rejoicing in sexual intimacy; the women (or "daughters") of Jerusalem form a chorus to the lovers, functioning as an audience whose participation in the lovers' erotic encounters facilitates the participation of the reader. So you must be asking yourself... Why in the world do we read Song of Songs on Passover?? שיר השירים א׳:ט׳-ט״ו Song of Songs 1:9-15 ֙ ֣ ֔ ֖ ְ ,I have likened you, my darling (9) (ט) ְל ֻס ָס ִתי ְּב ִר ְכ ֵבי ַפ ְרעֹה ִ ּד ִּמי ִתיך (To a mare in Pharaoh’s chariots: (10 ַר ְעיָ ִ ֽתי׃ (י) ָנא ֤ווּ ְל ָח ַ֙י ִי ְ֙ך ַּב ּתֹ ִ ֔רים Your cheeks are comely with plaited ַצ ָוּא ֵ ֖ר ְך ַּב ֲחרוּ ִזֽים׃ (יא) ּת ֹו ֵ ֤רי ָז ָה ֙ב wreaths, Your neck with strings of ַנ ֲע ֶׂשה־ ָּ֔ל ְך ִ ֖עם ְנ ֻק ּ֥ד ֹות ַה ָּכֽ ֶסף׃ (יב) jewels. (11) We will add wreaths of ַעד־ ׁ ֶ֤ש ַה ֶּ֙מ ֶל ְ֙ך ִּב ְמ ִס ּ֔ב ֹו ִנ ְר ִ ּ֖די ָנ ַ ֥תן ֵריחֽ ֹו׃ (gold To your spangles of silver. -

Ecclesiastes 12:9-14)

Chapter 3 Contextualizing the Voice of Qohelet: The Editors React (Ecclesiastes 12:9-14) vanity of vanities or futility of) הבל הבלים Following the verbal rumble of futilities) in Ecclesiastes 12:8, readers hear a shift in speaker. Ecclesiastes 12:9-14 provides a frame for understanding the location of the entire series of remarks from Ecclesiastes 1:1 on. As Tyler Atkinson notes, this speaker’s voice “remains in the background, as a transmitter of the protagonist’s words, not the creator of them.”1 Gary D. Salyer suggests that the tone of the Epilogue is that of an “obituary.”2 In a way, that tone makes particular sense, given that readers have just moved into chapter 12 through the process of aging and death—maybe even Qohelet’s own death. If, as this study contends, Qohelet speaks the whispers of a postcolonial discourse—a discourse primarily for the mind and heart and not for liberation in a political sense—then we might expect the framing device that ends the book in some way to provide an understanding of the entire book. Is Qohelet orthodox? Is Qohelet revolutionary? Is Qohelet to be taken seriously? Did Qohelet go too far or not far enough? Has this quest been an empirical exploration into the nature of survival under the administration of the Ptolemaic officials and their Jewish counterparts? All of these are valid questions. One aspect that is clearly missing in .king in Jerusalem) as noted in 1:1) מלך בירושלם the material, however, is the reference to Here the speaker—whether simply a variation on the Qoheletian voice or another 1. -

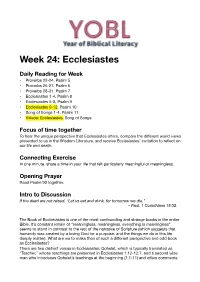

Week 24: Ecclesiastes

Week 24: Ecclesiastes Daily Reading for Week • Proverbs 22-24, Psalm 5 • Proverbs 25-27, Psalm 6 • Proverbs 28-31, Psalm 7 • Ecclesiastes 1-4, Psalm 8 • Ecclesiastes 5-8, Psalm 9 • Ecclesiastes 9-12, Psalm 10 • Song of Songs 1-4, Psalm 11 • Videos: Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs Focus of time together To hear the unique perspective that Ecclesiastes offers, compare the different world views presented to us in the Wisdom Literature, and receive Ecclesiastes’ invitation to reflect on our life and death. Connecting Exercise In one minute, share a time in your life that felt particularly meaningful or meaningless. Opening Prayer Read Psalm 90 together. Intro to Discussion If the dead are not raised, “Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die.” - Paul, 1 Corinthians 15:32. The Book of Ecclesiastes is one of the most confounding and strange books in the entire Bible. It’s constant refrain of “meaningless, meaningless, everything is meaningless” seems to stand in contrast to the rest of the narrative of Scripture (which suggests that humanity was created by a loving God for a purpose, and the things we do in this life deeply matter). What are we to make then of such a different perspective and odd book as Ecclesiastes? There are two distinct voices in Ecclesiastes: Qohelet, which is typically translated as “Teacher,” whose teachings are presented in Ecclesiastes 1:12-12:7, and a second wise man who introduces Qohelet’s teachings at the beginning (1:1-11) and offers comments at the end (12:8-14). The thrust of Qohelet’s teaching can be summed up by the verse from 1 Corinthians. -

In Search of Kohelet

IN SEARCH OF KOHELET By Christopher P. Benton Ecclesiastes is simultaneously one of the most popular and one of the most misunderstood books of the Bible. Too often one hears its key verse, “Vanity of vanities, all is vanity,” interpreted as simply an injunction against being a vain person. The common English translation of this verse (Ecclesiastes 1:2) comes directly from the Latin Vulgate, “Vanitas vanitatum, ominia vanitas.” However, the original Hebrew, “Havel havelim, hachol havel,” may be better translated as “Futility of futilities, all is futile.” Consequently, Ecclesiastes 1:2 is more a broad statement about the meaninglessness of life and actions that are in vain rather than personal vanity. In addition to the confusion that often surrounds the English translation of Ecclesiastes 1:2, the appellation for the protagonist in Ecclesiastes also loses much in the translation. In the enduring King James translation of the Bible, the speaker in Ecclesiastes is referred to as “the Preacher,” and in many other standard English translations of the Bible (Amplified Bible, New International Version, New Living Translation, American Standard Version) one finds the speaker referred to as either “the Preacher” or “the Teacher.” However, in the original Hebrew and in many translations by Jewish groups, the narrator is referred to simply as Kohelet. The word Kohelet is derived from the Hebrew root koof-hey-lamed meaning “to assemble,” and commentators suggest that this refers to either the act of assembling wisdom or to the act of meeting with an assembly in order to teach. Furthermore, in the Hebrew, Kohelet is generally used as a name, but in Ecclesiastes 12:8 it is also written as HaKohelet (the Kohelet) which is more suggestive of a title.