Ecclesiastes 12:1-8--Death, an Impetus for Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Emptiness Apart From

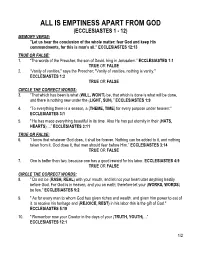

ALL IS EMPTINESS APART FROM GOD (ECCLESIASTES 1 - 12) MEMORY VERSE: "Let us hear the conclusion of the whole matter: fear God and keep His commandments, for this is man's all.” ECCLESIASTES 12:13 TRUE OR FALSE: 1. “The words of the Preacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem.” ECCLESIASTES 1:1 TRUE OR FALSE 2. “Vanity of vanities," says the Preacher; "Vanity of vanities, nothing is vanity." ECCLESIASTES 1:2 TRUE OR FALSE CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORDS: 3. “That which has been is what (WILL, WON’T) be, that which is done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the (LIGHT, SUN)." ECCLESIASTES 1:9 4. "To everything there is a season, a (THEME, TIME) for every purpose under heaven:" ECCLESIASTES 3:1 5. " He has made everything beautiful in its time. Also He has put eternity in their (HATS, HEARTS) ...” ECCLESIASTES 3:11 TRUE OR FALSE: 6. “I know that whatever God does, it shall be forever. Nothing can be added to it, and nothing taken from it. God does it, that men should fear before Him.” ECCLESIASTES 3:14 TRUE OR FALSE 7. One is better than two, because one has a good reward for his labor. ECCLESIASTES 4:9 TRUE OR FALSE CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORDS: 8. " Do not be (RASH, REAL) with your mouth, and let not your heart utter anything hastily before God. For God is in heaven, and you on earth; therefore let your (WORKS, WORDS) be few." ECCLESIASTES 5:2 9. " As for every man to whom God has given riches and wealth, and given him power to eat of it, to receive his heritage and (REJOICE, REST) in his labor-this is the gift of God." ECCLESIASTES 5:19 10. -

Ecclesiastes Song of Solomon

Notes & Outlines ECCLESIASTES SONG OF SOLOMON Dr. J. Vernon McGee ECCLESIASTES WRITER: Solomon. The book is the “dramatic autobiography of his life when he got away from God.” TITLE: Ecclesiastes means “preacher” or “philosopher.” PURPOSE: The purpose of any book of the Bible is important to the correct understanding of it; this is no more evident than here. Human philosophy, apart from God, must inevitably reach the conclusions in this book; therefore, there are many statements which seem to contra- dict the remainder of Scripture. It almost frightens us to know that this book has been the favorite of atheists, and they (e.g., Volney and Voltaire) have quoted from it profusely. Man has tried to be happy without God, and this book shows the absurdity of the attempt. Solomon, the wisest of men, tried every field of endeavor and pleasure known to man; his conclusion was, “All is vanity.” God showed Job, a righteous man, that he was a sinner in God’s sight. In Ecclesiastes God showed Solomon, the wisest man, that he was a fool in God’s sight. ESTIMATIONS: In Ecclesiastes, we learn that without Christ we can- not be satisfied, even if we possess the whole world — the heart is too large for the object. In the Song of Solomon, we learn that if we turn from the world and set our affections on Christ, we cannot fathom the infinite preciousness of His love — the Object is too large for the heart. Dr. A. T. Pierson said, “There is a danger in pressing the words in the Bible into a positive announcement of scientific fact, so marvelous are some of these correspondencies. -

Ecclesiastes 1

International King James Version Old Testament 1 Ecclesiastes 1 ECCLESIASTES Chapter 1 before us. All is Vanity 11 There is kno remembrance of 1 ¶ The words of the Teacher, the former things, neither will there be son of David, aking in Jerusalem. any remembrance of things that are 2 bVanity of vanities, says the Teacher, to come with those that will come vanity of vanities. cAll is vanity. after. 3 dWhat profit does a man have in all his work that he does under the Wisdom is Vanity sun? 12 ¶ I the Teacher was king over Is- 4 One generation passes away and rael in Jerusalem. another generation comes, but ethe 13 And I gave my heart to seek and earth abides forever. lsearch out by wisdom concerning all 5 fThe sun also rises and the sun goes things that are done under heaven. down, and hastens to its place where This mburdensome task God has it rose. given to the sons of men by which to 6 gThe wind goes toward the south be busy. and turns around to the north. It 14 I have seen all the works that are whirls around continually, and the done under the sun. And behold, all wind returns again according to its is vanity and vexation of spirit. circuits. 15 nThat which is crooked cannot 7 hAll the rivers run into the sea, yet be made straight. And that which is the sea is not full. To the place from lacking cannot be counted. where the rivers come, there they re- 16 ¶ I communed with my own heart, turn again. -

Ecclesiastes – “It’S ______About _____”

“DISCOVERING THE UNREAD BESTSELLER” Week 18: Sunday, March 25, 2012 ECCLESIASTES – “IT’S ______ ABOUT _____” BACKGROUND & TITLE The Hebrew title, “___________” is a rare word found only in the Book of Ecclesiastes. It comes from a word meaning - “____________”; in fact, it’s talking about a “_________” or “_________”. The Septuagint used the Greek word “__________” as its title for the Book. Derived from the word “ekklesia” (meaning “assembly, congregation or church”) the title again (in the Greek) can simply be taken to mean - “_________/_________”. AUTHORSHIP It is commonly believed and accepted that _________authored this Book. Within the Book, the author refers to himself as “the son of ______” (Ecclesiastes 1:1) and then later on (in Ecclesiastes 1:12) as “____ over _____ in Jerusalem”. Solomon’s extensive wisdom; his accomplishments, and his immense wealth (all of which were God-given) give further credence to his work. Outside the Book, _______ tradition also points to Solomon as author, but it also suggests that the text may have undergone some later editing by _______ or possibly ____. SNAPSHOT OF THE BOOK The Book of Ecclesiastes describes Solomon’s ______ for meaning, purpose and satisfaction in life. The Book divides into three different sections - (1) the _____ that _______ is ___________ - (Ecclesiastes 1:1-11); (2) the ______ that everything is meaningless (Ecclesiastes 1:12-6:12); and, (3) the ______ or direction on how we should be living in a world filled with ______ pursuits and meaninglessness (Ecclesiastes 7:1-12:14). That last section is important because the Preacher/Teacher ultimately sees the emptiness and futility of all the stuff people typically strive for _____ from God – p______ – p_______ – p________ - and p________. -

Ecclesiastes Devotionals

Read Ecclesiastes 1 That which has been is that which will be, and that which has been done is that which will be done. so there is nothing new under the sun. Eccl 1:9 I was a freshman in college, when a new friend of mine introduced me to his new found source of cash. He was selling phone cards, which were really big at the time because you didn't have a large group of people with cell phones. The idea was not only to sell the phone cards, but to get other people to sell them. You would get a cut of the sales of the people you later recruited, and he had been making real money to prove it. My dad called it a pyramid scheme, and I didn't really know what that was. Eventually the money and the company dried up and I saw Dad was right. Years later someone offered me a chance to make money selling a larger variety of items. I quickly realized I was looking at the same pyramid scheme, just with different components. I remembered the first lesson and kept my money. The book of Ecclesiastes was written by Solomon in his later years. He had more wisdom than anyone who ever lived on the earth, and yet he still had plenty of unwise decisions scattered behind him. And one of the great warnings that Solomon gives is that there's nothing new under the sun. As the internet has become more a part of our lives, it has brought as many problems as solutions. -

Ecclesiastes: the Philippians of the Old Testament

Ecclesiastes: The Philippians of the Old Testament Bereans Adult Bible Fellowship Placerita Baptist Church 2010 by William D. Barrick, Th.D. Professor of OT, The Master’s Seminary Chapter 12 Life Under a Setting Sun In conclusion, the Preacher determines to fear God, obey God, and enjoy life (9:1–12:14) Continuing the book’s grand finale (11:9–12:7), Solomon transitions from the enjoyment of “seeing the sun” to the approach of death. Assuming temporal existence for mankind “under the sun,” “he broadens the range of his observation to include God, who is above the sun, and death, which is beyond the sun.”1 When the wise contemplate death, they find all aspirations to grandeur and gain exposed as illusory visions of their own arrogance. Brown says of such contemplation, that it “purges the soul of all futile striving and, paradoxically, anxiety. The eternal sleep of death serves as a wake-up call to live and welcome the serendipities of the present.”2 Just as the setting sun signals the end of a day, so aging signals the approach of the close of one’s life. Preparation for the end of life must begin even in youth. “Before” in verses 1, 2, and 6 sets up a time-oriented series of statements that favor understanding the text as a description of the time of death, rather than merely a depiction of the process of aging.3 The first seven verses of this chapter comprise one long sentence.4 If someone were to read it aloud as one sentence, he or she would be “‘out of breath’ by the end”5—a play on the key word hebel, which can also mean “breath,” as well as “vanity,” “futility,” or “fleeting.” However, the interpreter would be remiss to focus too much upon death in this section. -

Ecclesiastes 12 Do It Now As We Begin the Last Chapter of Ecclesiastes Let Me Remind You of the Four Major Points of the Last Tw

Ecclesiastes 12 Do It Now As we begin the last chapter of Ecclesiastes let me remind you of the four major points of the last two chapters: 1. Life is an adventure – live it by faith, 2. Life is a gift – enjoy it, 3. Life is a stewardship – live it for the glory of God and 4. Life is short – therefore serve God now. This is what the last chapter is all about, serve God, do it now, before it’s too late. We don’t serve God because He needs something from us. Acts 17 tells us that God is not served by our works as though he needed anything “since He gives to all life, breath and all things.”1 We serve God by loving Him and obeying Him and in return our lives are filled with His grace, power and love. Here in the last chapter of Ecclesiastes the call to serve God now is made specifically to young people. Someone has said that youth is for pleasure, middle age is for business and old age is for religion. That is a frightful delusion. We need to love and serve God now, for our own wellbeing, because tomorrow is never guaranteed. So let’s begin. Remember now your Creator in the days of your youth, Before the difficult days come, And the years draw near when you say, “I have no pleasure in them”: (Ecclesiastes 12:1) Remember your Creator. Think carefully about your Creator. Live in His presence daily. Seek to discover His greatness and glory now. -

![Commentary on Ecclesiastes 11:9-12:7, 13 [14] by L.G](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2509/commentary-on-ecclesiastes-11-9-12-7-13-14-by-l-g-1042509.webp)

Commentary on Ecclesiastes 11:9-12:7, 13 [14] by L.G

Commentary on Ecclesiastes 11:9-12:7, 13 [14] By L.G. Parkhurst, Jr. The International Bible Lesson (Uniform Sunday School Series) for Sunday, October 16, 2011, is from Ecclesiastes 11:9-12:7, 13. Five Questions for Discussion and Thinking Further follow the Bible Lesson Commentary below. Study Hints for Thinking Further, which are also available on the Bible Lesson Forum, will aid teachers in conducting class discussion. Ecclesiastes 11:9-12:7, 13 [14] (Ecclesiastes 11:9) Rejoice, young man, while you are young, and let your heart cheer you in the days of your youth. Follow the inclination of your heart and the desire of your eyes, but know that for all these things God will bring you into judgment. Solomon’s book tells young people to enjoy being young while they can, for they will soon be old. He also tells young people the choice before them. They can do what they want (set their own goals and follow their feelings) or they can “keep God’s commandments” (see Ecclesiastes 12:13). If they obey or disobey God when following their feelings or setting their own goals, then God will judge whether their choices and actions are right or wrong, good or evil (see Ecclesiastes 12:14). God will hold everyone accountable and responsible for their way of life. (Ecclesiastes 11:10) Banish anxiety from your mind, and put away pain from your body; for youth and the dawn of life are vanity. The “dawn of life” (meaning “infancy and childhood”) and youth are vanity or meaningless depending on what a child or youth plans to do and what actions they take. -

Einführung Jonathan Magonet

“Wisdom has built her house” (Prov. 9:1) th 49 International Jewish-Christian Bible Week משלי – The Book of Proverbs 23rd to 30th July 2017 INTRODUCTION TO THE BOOK OF PROVERBS Jonathan Magonet The Book of Proverbs is an intriguing mixture of materials. It has an overall organising structure with opening exhortations to follow the path of wisdom and avoid the path of folly, and a post- script. But the bulk of the book consists of a variety of anthologies of proverbs, or, as they are sometimes characterised, miniature parables. They cover many different aspects of life, seemingly arranged at random. There are attempts to find some patterns underlying them. However, per- haps this randomness is meant to model the accidental nature of life itself, whereby the chance bits of advice or wisdom that we accumulate may prove helpful at certain times. The Book is customarily grouped with Ecclesiastes and Job as examples of ‘wisdom literature’. All three are located in the third division of the Hebrew Bible, Ketuvim , ‘Writings’. This would classify them, in rabbinic thought, as human compositions, inspired by the ‘ ruach ha-kodesh ’, the ‘holy spirit’, but not examples of direct divine revelation. The Book is credited to King Solomon, which must go some way to explaining why it was includ- ed in the Hebrew Bible. But can we learn something more from within the Book itself to explain why it was thought to be necessary to include it in the Biblical library? According to the Biblical record Solomon was the composer, collector and editor of wisdom say- ings (1 Kings 5:12; Ecclesiastes 12:9). -

Ecclesiastes 12:9-14)

Chapter 3 Contextualizing the Voice of Qohelet: The Editors React (Ecclesiastes 12:9-14) vanity of vanities or futility of) הבל הבלים Following the verbal rumble of futilities) in Ecclesiastes 12:8, readers hear a shift in speaker. Ecclesiastes 12:9-14 provides a frame for understanding the location of the entire series of remarks from Ecclesiastes 1:1 on. As Tyler Atkinson notes, this speaker’s voice “remains in the background, as a transmitter of the protagonist’s words, not the creator of them.”1 Gary D. Salyer suggests that the tone of the Epilogue is that of an “obituary.”2 In a way, that tone makes particular sense, given that readers have just moved into chapter 12 through the process of aging and death—maybe even Qohelet’s own death. If, as this study contends, Qohelet speaks the whispers of a postcolonial discourse—a discourse primarily for the mind and heart and not for liberation in a political sense—then we might expect the framing device that ends the book in some way to provide an understanding of the entire book. Is Qohelet orthodox? Is Qohelet revolutionary? Is Qohelet to be taken seriously? Did Qohelet go too far or not far enough? Has this quest been an empirical exploration into the nature of survival under the administration of the Ptolemaic officials and their Jewish counterparts? All of these are valid questions. One aspect that is clearly missing in .king in Jerusalem) as noted in 1:1) מלך בירושלם the material, however, is the reference to Here the speaker—whether simply a variation on the Qoheletian voice or another 1. -

Kohelet: Sanctifying the Human Perspective

Kohelet: Sanctifying the Human Perspective Byline: Rabbi Hayyim Angel [1] KOHELET [2] SANCTIFYING THE HUMAN PERSPECTIVE INTRODUCTION Tanakh is intended to shape and guide our lives. Therefore, seeking out peshat—the primary intent of the authors of Tanakh—is a religious imperative and must be handled with great care and responsibility. Our Sages recognized a hazard inherent to learning. In attempting to understand the text, nobody can be truly detached and objective. Consequently, people’s personal agendas cloud their ability to view the text in an unbiased fashion. An example of such a viewpoint is the verse, “let us make man” from the creation narrative, which uses the plural “us” instead of the singular “me” (Gen. 1:26): R. Samuel b. Nahman said in R. Jonatan’s name: When Moses was engaged in writing the Torah, he had to write the work of each day. When he came to the verse, “And God said: Let Us make man,” etc., he said: “Sovereign of the Universe! Why do You furnish an excuse to heretics (for maintaining a plurality of gods)?” “Write,” replied He; “And whoever wishes to err will err.” (Gen. Rabbah 8:8) The midrash notes that there were those who were able to derive support for their theology of multiple deities from the this verse, the antithesis of a basic Torah value. God would not compromise truth because some people are misguided. It also teaches that if they wish, people will be able to find pretty much anything as support for their agendas under the guise of scholarship. Whoever wishes to err will err. -

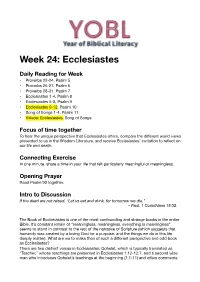

Week 24: Ecclesiastes

Week 24: Ecclesiastes Daily Reading for Week • Proverbs 22-24, Psalm 5 • Proverbs 25-27, Psalm 6 • Proverbs 28-31, Psalm 7 • Ecclesiastes 1-4, Psalm 8 • Ecclesiastes 5-8, Psalm 9 • Ecclesiastes 9-12, Psalm 10 • Song of Songs 1-4, Psalm 11 • Videos: Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs Focus of time together To hear the unique perspective that Ecclesiastes offers, compare the different world views presented to us in the Wisdom Literature, and receive Ecclesiastes’ invitation to reflect on our life and death. Connecting Exercise In one minute, share a time in your life that felt particularly meaningful or meaningless. Opening Prayer Read Psalm 90 together. Intro to Discussion If the dead are not raised, “Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die.” - Paul, 1 Corinthians 15:32. The Book of Ecclesiastes is one of the most confounding and strange books in the entire Bible. It’s constant refrain of “meaningless, meaningless, everything is meaningless” seems to stand in contrast to the rest of the narrative of Scripture (which suggests that humanity was created by a loving God for a purpose, and the things we do in this life deeply matter). What are we to make then of such a different perspective and odd book as Ecclesiastes? There are two distinct voices in Ecclesiastes: Qohelet, which is typically translated as “Teacher,” whose teachings are presented in Ecclesiastes 1:12-12:7, and a second wise man who introduces Qohelet’s teachings at the beginning (1:1-11) and offers comments at the end (12:8-14). The thrust of Qohelet’s teaching can be summed up by the verse from 1 Corinthians.