HEPTADIC VERBAL PATTERNS in the SOLOMON NARRATIVE of 1 KINGS 1–11 John A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solomon's Legacy

Solomon’s Legacy Divided Kingdom Image from: www.lightstock.com Solomon’s Last Days -1 Kings 11 Image from: www.lightstock.com from: Image ➢ God raises up adversaries to Solomon. 1 Kings 11:14 14 Then the LORD raised up an adversary to Solomon, Hadad the Edomite; he was of the royal line in Edom. 1 Kings 11:23-25 23 God also raised up another adversary to him, Rezon the son of Eliada, who had fled from his lord Hadadezer king of Zobah. 1 Kings 11:23-25 24 He gathered men to himself and became leader of a marauding band, after David slew them of Zobah; and they went to Damascus and stayed there, and reigned in Damascus. 1 Kings 11:23-25 25 So he was an adversary to Israel all the days of Solomon, along with the evil that Hadad did; and he abhorred Israel and reigned over Aram. Solomon’s Last Days -1 Kings 11 Image from: www.lightstock.com from: Image ➢ God tells Jeroboam that he will be over 10 tribes. 1 Kings 11:26-28 26 Then Jeroboam the son of Nebat, an Ephraimite of Zeredah, Solomon’s servant, whose mother’s name was Zeruah, a widow, also rebelled against the king. 1 Kings 11:26-28 27 Now this was the reason why he rebelled against the king: Solomon built the Millo, and closed up the breach of the city of his father David. 1 Kings 11:26-28 28 Now the man Jeroboam was a valiant warrior, and when Solomon saw that the young man was industrious, he appointed him over all the forced labor of the house of Joseph. -

1 Kings 10) Notes: Week Eight

Lessons from Solomon: Celebrating God’s Provision (1 Kings 10) Notes: Week Eight 1 Kings 10 (HCSB) The Queen of Sheba 10 The queen of Sheba heard about Solomon’s fame connected with the name of Yahweh and came to test him with difficult questions. 2 She came to Jerusalem with a very large entourage, with camels bearing spices, gold in great abundance, and precious stones. She came to Solomon and spoke to him about everything that was on her mind. 3 So Solomon answered all her questions; nothing was too difficult for the king to explain to her. 4 When the queen of Sheba observed all of Solomon’s wisdom, the palace he had built, 5 the food at his table, his servants’ residence, his attendants’ service and their attire, his cupbearers, and the burnt offerings he offered at the LORD’s temple, it took her breath away. 6 She said to the king, “The report I heard in my own country about your words and about your wisdom is true. 7 But I didn’t believe the reports until I came and saw with my own eyes. Indeed, I was not even told half. Your wisdom and prosperity far exceed the report I heard. 8 How happy are your men.[a] How happy are these servants of yours, who always stand in your presence hearing your wisdom. 9 May Yahweh your God be praised! He delighted in you and put you on the throne of Israel, because of the LORD’s eternal love for Israel. He has made you king to carry out justice and righteousness.” 10 Then she gave the king four and a half tons[b] of gold, a great quantity of spices, and precious stones. -

1 Kings 11:14-40 “Solomon's Adversaries”

1 Kings 11:14-40 “Solomon’s Adversaries” 1 Kings 11:9–10 9 So the LORD became angry with Solomon, because his heart had turned from the LORD God of Israel, who had appeared to him twice, 10 and had commanded him concerning this thing, that he should not go after other gods; but he did not keep what the LORD had commanded. Where were the Prophets David had? • To warn Solomon of his descent into paganism. • To warn Solomon of how he was breaking the heart of the Lord. o Do you have friends that care enough about you to tell you when you are backsliding against the Lord? o No one in the Electronic church to challenge you, to pray for you, to care for you. All of these pagan women he married (for political reasons?) were of no benefit. • Nations surrounding Israel still hated Solomon • Atheism, Agnostics, Gnostics, Paganism, and Legalisms are never satisfied until you are dead – and then it turns to kill your children and grandchildren. Exodus 20:4–6 4 “You shall not make for yourself a carved image—any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth; 5 you shall not bow down to them nor serve them. For I, the LORD your God, am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children to the third and fourth generations of those who hate Me, 6 but showing mercy to thousands, to those who love Me and keep My commandments. -

Books in the Treasury

Books in the Treasury I went forth unto the treasury of Laban. And as I went forth towards the treasury of Laban, behold, I saw the servant of Laban who had the keys of the treasury. And I commanded him in the voice of Laban, that he should go with me into the treasury. And he supposed me to be his master, Laban, for he beheld the garments and also the sword girded about my loins. And he spake unto me concerning the elders of the Jews, he knowing that his master, Laban, had been out by night among them. And I spake unto him as if it had been Laban. And I also spake unto him that I should carry the engravings, which were upon the plates of brass, to my elder brethren, who were without the walls. (1 Nephi 4:20–24) The earliest records possessed by the Nephites were the brass plates brought from Jerusalem. These plates had been kept in “the treasury of Laban,” whence Nephi retrieved them. The concept of keeping books in a treasury, while strange to the modern mind, was a common practice anciently, and the term often denoted what we would today call a library. Ezra 5:17–6:2 speaks of a “treasure house” containing written records. The Aramaic word rendered “treasure” in this passage is ginzayyâ, from the root meaning “to keep, hide” in both Hebrew and Aramaic. In Esther 3:9 and 4:7, the Hebrew word of the same origin is used to denote a treasury where money is kept. -

The New 'Ain Dara Temple: Closest Solomonic Parallel1

The New ‘Ain Dara Temple: Closest Solomonic Parallel1 By John Monson A stunning parallel to Solomon’s Temple has been discovered in northern Syria. The temple at ‘Ain Dara has far more in common with the Jerusalem Temple described in the Book of Kings than any other known building. Yet the newly excavated temple has received almost no attention in this country, at least partially because the impressive excavation report, published a decade ago, was written in German by a Syrian scholar and archaeologist. For centuries, readers of the Bible have tried to envision Solomon’s glorious Jerusalem Temple, dedicated to the Israelite God, Yahweh. Nothing of Solomon’s Temple remains today; the Babylonians destroyed it utterly in 586 B.C.E. And the vivid Biblical descriptions are of limited help in reconstructing the building: Simply too many architectural terms have lost their meaning over the ensuing centuries, and too many details are absent from the text. Slowly, however, archaeologists are beginning to fill in the gaps in our knowledge of Solomon’s building project. For years, pride of place went to the temple at Tell Ta‘yinat, also in northern Syria. When it was discovered in 1936, the Tell Ta‘yinat temple, unlike the ‘Ain Dara temple, caused a sensation because of its similarities to Solomon’s Temple. Yet the ‘Ain Dara temple is closer in time to Solomon’s Temple by about a century (it is, in fact, essentially contemporaneous), is much closer in size to Solomon’s Temple than the smaller Tell Ta‘yinat temple, has several features found in Solomon’s Temple but not in the Tell Ta‘yinat temple, and is far better preserved than the Tell Ta‘yinat temple. -

Bible Chronology of the Old Testament the Following Chronological List Is Adapted from the Chronological Bible

Old Testament Overview The Christian Bible is divided into two parts: the Old Testament and the New Testament. The word “testament” can also be translated as “covenant” or “relationship.” The Old Testament describes God’s covenant of law with the people of Israel. The New Testament describes God’s covenant of grace through Jesus Christ. When we accept Jesus as our Savior and Lord, we enter into a new relationship with God. Christians believe that ALL Scripture is “God-breathed.” God’s Word speaks to our lives, revealing God’s nature. The Lord desires to be in relationship with His people. By studying the Bible, we discover how to enter into right relationship with God. We also learn how Christians are called to live in God’s kingdom. The Old Testament is also called the Hebrew Bible. Jewish theologians use the Hebrew word “Tanakh.” The term describes the three divisions of the Old Testament: the Law (Torah), the Prophets (Nevi’im), and the Writings (Ketuvim). “Tanakh” is composed of the first letters of each section. The Law in Hebrew is “Torah” which literally means “teaching.” In the Greek language, it is known as the Pentateuch. It comprises the first five books of the Old Testament: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. This section contains the stories of Creation, the patriarchs and matriarchs, the exodus from Egypt, and the giving of God’s Law, including the Ten Commandments. The Prophets cover Israel’s history from the time the Jews entered the Promised Land of Israel until the Babylonian captivity of Judah. -

Septuagint Vs. Masoretic Text and Translations of the Old Testament

#2 The Bible: Origin & Transmission November 30, 2014 Septuagint vs. Masoretic Text and Translations of the Old Testament The Septuagint (Greek translation of the Old Testament) captured the Original Hebrew Text before Mistakes crept in. Psalm 119:89 Forever, O LORD, Your word is settled in heaven. 2 Timothy 3:16 All Scripture is inspired breathed by God 2 Peter 1:20-21 No prophecy of Scripture is a matter of one's own interpretation, for no prophecy was ever made by an act of human will, but men moved by the but men carried along by Holy Spirit spoke from God. Daniel 8:5 While I was observing, behold, a male goat was coming from the west over the surface of the whole earth without touching the ground 1 Kings 4:26 Solomon had 40,000 stalls of horses for his chariots, and 12,000 horsemen. 2 Chronicles 9:25 Now Solomon had 4,000 stalls for horses and chariots and 12,000 horsemen, 1 Kings 5:15-16 Now Solomon had 70,000 transporters, and 80,000 hewers of stone in the mountains, besides Solomon's 3,300 chief deputies who were over the project and who ruled over the people who were doing the work. 2 Chronicles 2:18 He appointed 70,000 of them to carry loads and 80,000 to quarry stones in the mountains and 3,600 supervisors . Psalm 22:14 (Masoretic) I am poured out like water, and all my bones are out of joint; My heart is like wax; it is melted within me. -

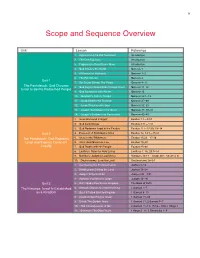

Scope and Sequence Overview

9 Scope and Sequence Overview Unit Lesson Reference 1. Approaching the Old Testament Introduction 2. The One Big Story Introduction 3. Preparing to Read God's Word Introduction 4. God Creates the World Genesis 1 5. A Mission for Humanity Genesis 1–2 6. The Fall into Sin Genesis 3 Unit 1 7. Sin Grows Worse: The Flood Genesis 4–11 The Pentateuch: God Chooses 8. God Begins Redemption through Israel Genesis 11–12 Israel to Be His Redeemed People 9. God Covenants with Abram Genesis 15 10. Abraham's Faith Is Tested Genesis 22:1–19 11. Jacob Inherits the Promise Genesis 27–28 12. Jacob Wrestles with God Genesis 32–33 13. Joseph: God Meant It for Good Genesis 37; 39–41 14. Joseph's Brothers Are Reconciled Genesis 42–45 1. Israel Enslaved in Egypt Exodus 1:1—2:10 2. God Calls Moses Exodus 2:11—4:31 3. God Redeems Israel in the Exodus Exodus 11:1–12:39; 13–14 Unit 2 4. Passover: A Redemption Meal Exodus 12; 14:1—15:21 The Pentateuch: God Redeems 5. Israel in the Wilderness Exodus 15:22—17:16 Israel and Expects Covenant 6. Sinai: God Gives His Law Exodus 19–20 Loyalty 7. God Dwells with His People Exodus 25–40 8. Leviticus: Rules for Holy Living Leviticus 1; 16; 23:9–14 9. Numbers: Judgment and Mercy Numbers 13:17—14:45; 20:1–13; 21:4–8 10. Deuteronomy: Love the Lord! Deuteronomy 28–34 1. Conquering the Promised Land Joshua 1–12 2. -

2 KINGS Editorial Consultants Athalya Brenner-Idan Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza

2 KINGS Editorial Consultants Athalya Brenner-Idan Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza Editorial Board Mary Ann Beavis Carol J. Dempsey Gina Hens-Piazza Amy-Jill Levine Linda M. Maloney Ahida Pilarski Sarah J. Tanzer Lauress Wilkins Lawrence WISDOM COMMENTARY Volume 12 2 Kings Song-Mi Suzie Park Ahida Calderón Pilarski Volume Editor Barbara E. Reid, OP General Editor A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical Press Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, © 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. © 2019 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever, except brief quotations in reviews, without written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, MN 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Park, Song-Mi Suzie, author. Title: 2 Kings / Song-Mi Suzie Park ; Ahida Calderón Pilarski, volume editor ; Barbara E. Reid, OP, general editor. Other titles: Second Kings Description: Collegeville : Liturgical Press, 2019. | Series: Wisdom commentary ; Volume 12 | “A Michael Glazier book.” | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019019581 (print) | LCCN 2019022046 (ebook) | ISBN -

Othb6313 Hebrew Exegesis: 1 & 2 Kings

OTHB6313 HEBREW EXEGESIS: 1 & 2 KINGS Dr. R. Dennis Cole Fall 2015 Campus Box 62 3 Hours (504)282-4455 x 3248 Email: [email protected] Seminary Mission Statement: The mission of New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary is to equip leaders to fulfill The Great Commission and The Great Commandments through the local church and its ministries. Course Description: This course combines an overview of 1 & 2 Kings and its place in the Former Prophets with an in-depth analysis of selected portions of the Hebrew text. Primary attention will be given to the grammatical, literary, historical, and theological features of the text. The study will include a discussion of the process leading to hermeneutical goals of teaching and preaching. Student Learning Outcomes: Upon the successful completion of this course the student will have demonstrated a proper knowledge of and an ability to use effectively in study, teaching and preaching: 1. The overall literary structure and content of 1 & 2 Kings. 2. The major theological themes and critical issues in the books. 3. The Hebrew text of 1 & 2 Kings. 4. Hebrew syntax and literary stylistics. NOBTS Core Values Addressed: Doctrinal Integrity: Knowledge and Practice of the Word of God Characteristic Excellence: Pursuit of God’s Revelation with Diligence Spiritual Vitality: Transforming Power of God’s Word Mission Focus: We are here to change the world by fulfilling the Great Commission and the Great Commandments through the local church and its ministries. This is the 2015-16 core value focus. Textbooks: Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia. 1 Kings, Simon DeVries (Word Biblical Commentary) 2 Kings, T.R. -

The Temple Prayer of Solomon (1 Kings 8:1-9:9)

1 The Temple Prayer of Solomon (1 Kings 8:1-9:9) By Ted Hildebrandt The Temple Prayer of Solomon in 1 Kings 8 and the divine response in 1 Kings 9 create one of the longest and most fascinating prayer narratives in the Old Testament. There are several questions we will seek to explore in this presentation paper. How does this prayer fit into the 1 Kings 1-11 narrative? What may be learned from ancient Near Eastern parallels concerning kings building and dedicating temples? What kinds of intertextual influences have impacted the shape of this prayer? How is one to understand the elusive character of Solomon from his prayer? How are the suppliants portrayed in the prayer? What do the seven Prayer Occasions (8:31-51) reveal about the types of situations which prompt prayer? How is God portrayed in this prayer? How does Solomon’s Temple Prayer fit into the literary structure of 1 Kings 1-11? In order to understand the framework of the Solomonic narrative of 1 Kings 1-11 in which the temple prayer is set, the literary structure should be noted before jumping into the prayer itself. The following is a useful chiastic structural diagram giving an overview of this narrative (adapted from Parker, 43; Williams, 66). 2 Frame Story chs. 1-2 [Adversaries: Adonijah, Joab, Abiathar] 1. Dream #1 3:1-15 [Asks for Wisdom at Gibeon high place] A Domestic 2. Women and Wisdom [Two women/one baby] 3:16-28 Policy 3. Administration and Wisdom 4:1-5:14 Favorable to Solomon B Labour 4. -

Solomon, the Wise King Scripture: 2 Chronicles 1:1-13; 1 Kings 3:7-15

5 Scripture: 2 Chronicles 1:1-13; 1 Kings 3:7-15 The Wise King Track 28 The young King Solomon stood up before all the important grown-ups in Israel. He started to talk, but they stopped him with their questions: “When will you “How will you keep start building peace in the land “Will you be a good God’s temple?” of Israel?” king, just like your father, David, was?” 1 of 6 © 2009 Awana® Clubs International 5 Scripture: 2 Chronicles 1:1-13; 1 Kings 3:7-15 Solomon looked at all the faces before him. There were more faces than he could ever count! Suddenly, he felt very small. He didn’t know the answers to any of their questions. He didn’t know how to be a king. Oh, if only his father, King David, were still alive to tell him what to do! Then Solomon had an idea. He said to the people, “Let’s go to Gibeon and worship the Lord at His special tent, the tabernacle.” At the tabernacle, Solomon and all the people prayed to the Lord. Solomon gave a thousand of his best animals to the Lord as an offering. © 2009 Awana® Clubs International 5 Scripture: 2 Chronicles 1:1-13; 1 Kings 3:7-15 That night, while Solomon slept, God came to him in a dream. God said He would give Solomon whatever he asked for. Right away, Solomon knew what he wanted. He said, “Lord, you have loved my father, David. You have chosen me to take his job as king.