Embellishments of the Alaska Native Gut Parka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Know Your Body Know Your Style

KNOW YOUR BODY KNOW YOUR STYLE Our bodies are classified according to certain specific types of silhouettes. You will learn about your body type, the clothes that favor each silhouette and those that should definitely be avoided. Your body shape may have traits of two types of silhouettes. Stand in front of a full-length mirror in your underwear and carefully study your body shape. Regardless of whether you are slim or plump, your body will tend to predominantly conform to one of the body types described below. Knowing your silhouette, you will be able to know what type of outfits that will make you look great, and which ones you should avoid as they throw the shape of your body off balance. 2020 Playfication Learning, LLC © PagePage 1 of 1 8 of 8 HOURGLASS SHAPE This type of female figure is typically considered the perfect figure because it is the most proportionate. It is the most versatile body shape and practically everything that women with this figure wear looks good on them. However, you should avoid falling into exaggerations that unbalance your body. You have an hourglass figure, when your shoulders and hips measure the same, and your waist is narrower. You have a balanced and symmetrical body. Clothes that lengthen your body will accentuate your figure and make you look great. What to wear: 1. Wrap dresses and “A” shaped skirts 2. Dresses with a defined waist and knee-length skirts highlighting your curves 3. Solid colors 4. Two-piece dresses 5. Shirt dresses with a waist belt 6. -

Glossary of Sewing Terms

Glossary of Sewing Terms Judith Christensen Professional Patternmaker ClothingPatterns101 Why Do You Need to Know Sewing Terms? There are quite a few sewing terms that you’ll need to know to be able to properly follow pattern instructions. If you’ve been sewing for a long time, you’ll probably know many of these terms – or at least, you know the technique, but might not know what it’s called. You’ll run across terms like “shirring”, “ease”, and “blousing”, and will need to be able to identify center front and the right side of the fabric. This brief glossary of sewing terms is designed to help you navigate your pattern, whether it’s one you purchased at a fabric store or downloaded from an online designer. You’ll find links within the glossary to “how-to” videos or more information at ClothingPatterns101.com Don’t worry – there’s no homework and no test! Just keep this glossary handy for reference when you need it! 2 A – Appliqué – A method of surface decoration made by cutting a decorative shape from fabric and stitching it to the surface of the piece being decorated. The stitching can be by hand (blanket stitch) or machine (zigzag or a decorative stitch). Armhole – The portion of the garment through which the arm extends, or a sleeve is sewn. Armholes come in many shapes and configurations, and can be an interesting part of a design. B - Backtack or backstitch – Stitches used at the beginning and end of a seam to secure the threads. To backstitch, stitch 2 or 3 stitches forward, then 2 or 3 stitches in reverse; then proceed to stitch the seam and repeat the backstitch at the end of the seam. -

Kalemie L'oubliee Kalemie the Forgotten Mwiba Lodge, Le Safari Version Luxe Mexico Insolite Not a Stranger in a Familiar La

JUILLET-AOUT-SEPTEMBRE 2018 N° 20 TRIMESTRIEL N° 20 5 YEARS ANNIVERSARY 5 ANS DÉJÀ LE VOYAGE EN AFRIQUE TRAVEL in AFRICA LE VOYAGE EN AFRIQUE HAMAJI MAGAZINE N°20 • JUILLET-AOUT-SEPTEMBRE 2018 N°20 • JUILLET-AOUT-SEPTEMBRE HAMAJI MAGAZINE MEXICO INSOLITE Secret Mexico GRAND ANGLE MWIBA LODGE, LE SAFARI VERSION LUXE Mwiba Lodge, luxury safari at its most sumptuous VOYAGE NOT A STRANGER KALEMIE L’OUBLIEE IN A FAMILIAR LAND KALEMIE THE FORGOTTEN Par Sarah Waiswa Sur une plage du Tanganyika, l’ancienne Albertville — On the beach of Tanganyika, the old Albertville 1 | HAMAJI JUILLET N°20AOÛT SEPTEMBRE 2018 EDITOR’S NEWS 6 EDITO 7 CONTRIBUTEURS 8 CONTRIBUTORS OUR WORLD 12 ICONIC SPOT BY THE TRUST MERCHANT BANK OUT OF AFRICA 14 MWIBA LODGE : LE SAFARI DE LUXE À SON SUMMUM LUXURY SAFARI AT ITS MOST SUMPTUOUS ZOOM ECO ÉCONOMIE / ECONOMY TAUX D’INTÉRÊTS / INTEREST RATES AFRICA RDC 24 Taux d’intérêt moyen des prêts — Average loan interest rates, % KALEMIE L'OUBLIÉE — THE FORGOTTEN Taux d’intérêt moyen des dépôts d’épargne — Average interest TANZANIE - 428,8 30 % rates on saving deposits, % TANZANIA AT A GLANCE BALANCE DU COMPTE COURANT EN MILLION US$ 20 % CURRENT ACCOUNT AFRICA 34 A CHAQUE NUMERO HAMAJI MAGAZINE VOUS PROPOSE UN COUP D’OEIL BALANCE, MILLION US$ SUR L’ECONOMIE D’UN PAYS EN AFRIQUE — IN EVERY ISSUE HAMAJI MAGAZINE OFFERS 250 YOU A GLANCE AT AN AFRICAN COUNTRY’S ECONOMY 10 % TRENDY ACCRA, LA CAPITALE DU GHANA 0 SOURCE SOCIAL ECONOMICS OF TANZANIE 2016 -250 -500 0 DENSITÉ DE POPULATION PAR RÉGION / POPULATION DENSITY PER REGION 1996 -

First Nations Perspectives on Sea Otter Conservation in British Columbia and Alaska: Insights Into Coupled Human Àocean Systems

Chapter 11 First Nations Perspectives on Sea Otter Conservation in British Columbia and Alaska: Insights into Coupled Human ÀOcean Systems Anne K. Salomon 1, Kii’iljuus Barb J. Wilson 2, Xanius Elroy White 3, Nick Tanape Sr. 4 and Tom Mexsis Happynook 5 1School of Resource and Environmental Management, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada, 2Skidegate, Haida Gwaii, BC, Canada, 3Bella Bella, BC, Canada, 4Nanwalek, AK, USA, 5Uu-a-thluk Council of Ha’wiih, Huu-ay-aht, BC, Canada Sea Otter Conservation. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801402-8.00011-1 © 2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 301 302 Sea Otter Conservation INTRODUCTION: REGIME SHIFTS AND TRANSFORMATIONS ALONG NORTH AMERICA’S NORTHWEST COAST One of our legends explains that the sea otter was originally a man. While col- lecting chitons he was trapped by an incoming tide. To save himself, he wished to become an otter. His transformation created all otters. Alutiiq Museum and Archaeological Repository (2005) Human interactions with sea otters and kelp forest ecosystems have spanned millennia ( Figure 11.1 ; Rick et al., 2011 ). In fact, archeological evidence suggests that the highly productive kelp forests of the Pacific Rim may have sustained the original coastal ocean migration route of maritime people to the Americas near the end of the Pleistocene ( Erlandson et al., 2007 ). Similarly, many coastal First Nations stories speak of ancestors who came from the sea (Boas, 1932; Brown and Brown, 2009; Guujaaw, 2005; Swanton, 1909). Yet this vast and aqueous “kelp highway,” providing food, tools, trade goods, and safe anchorage for sophisticated watercraft, would have been highly susceptible to overgrazing by sea urchins had it not been FIGURE 11.1 Sea otter pictographs from Kachemak Bay, Alaska. -

The Cloth Parka

CCM-00072 UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS The Cloth Parka Introduction face can stand some exposure if forehead and cheeks are protected Making cloth parkas is fun if one has done some with a ruff of long, shaggy fur sewing before and if simple designs are used. The around the face. A scarf over the cloth parka is a traditional item of clothing for mouth is not good, as it soon Alaska Natives and is popular with non-Native becomes frosted and icy. people living in Alaska as well. It is a practical way of staying warm and combines both Native and Roomy. A loose parka Western design techniques. The parka always has permits easy circulation of a hood, and a zipper is used for the front closing, blood, saves heat and wears although some sort of additional fastening should better. A good parka has be included for anyone who might have trouble with large armholes and is loose a zipper when the weather is extremely cold. Loop across the shoulders but is buttonholes or frogs could be used with buttons. belted and snug at the hips. To avoid wasting expensive materials one should Mittens should be loose enough take time to make a test pattern. Only experienced to double your fist. seamstresses should make the parka without a test shell. Boots or mukluks should be large enough for extra socks and inner The beginner should use easy-to-sew materials and soles and loose enough to wiggle simple trimmings. A very effective parka can be your toes. -

Robert Vintage Pajamas Classic Styles Also Matter When You Put Little Ones to Bed

1-800-543-6915 www.childrenscornerpatterns.com Robert Vintage Pajamas Classic styles also matter when you put little ones to bed. Now that our Robert pattern is available in a wider range of sizes, you can make these vintage pajamas for all your little ladies and gents. Supplies Robert Children’s Corner pattern Piping – 3 yards Tracing Paper Notions per the pattern Fabric Requirements (in yards) Sizes 6m-24mo 3-6 7-8 10-14 7 1 3 45" wide 1 /8 2 /4 3 3 /8 7 1 5 3 54/60" wide 1 /8 2 /4 2 /8 2 /4 Cutting Instructions 1. Trace shirt front using tracing paper starting and stopping at placket fold line. Measure ¼” over from the fold line toward the facing, and draw a line parallel to the fold line. Connect this line to the neckline and the hem. This is your new shirt front pattern piece. Cutting Layout aamas old ine old 45/54 wide sizes 6mo-6} Fold hirt ac ollar ocet odiied ants ront asitand ocet Cuff odiied hirt ront hirt Cuff on leee ants Cuff odiied ants ac acin Selvae 45 wide sizes -14} 2. Place tracing paper on the original shirt front again, Fold ocet ollar acin and measure ¼” from the fold line toward the shirt hirt ac odiied asitand hirt ront ocet front. Draw a line parallel to the fold line. Continue Cuff ants Cuff on leee tracing the front facing. This piece should be 1 ½” hirt Cuff odiied ants ront wide. This is your new facing piece. -

Confidential the District Solicitied 401 Suppliers and Received 9 Responses

BID TABULATION GARLAND INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT Auction Title:168-20 Bid Rfq Softball Uniforms & Num:32339 Equipment *Confidential Ln # Award (Y/N) Reason Item Description Quantity UOM Supplier Price Extended Price 1 NA Dudley Thunder Heat Yellow Softballs 40 DZ SCHOOL SPECIALTY INC NB NB with Red stitching & NFHS STAMP #WT12YFP, core .47 – 12”, no subs district game ball Y PYRAMID SCHOOL PRODUCTS 62.00 2,480.00 AMERICA TEAM SPORTS 64.00 2,560.00 VARSITY BRANDS HOLDINGS CO 69.91 2,796.40 INC DAN CAREYS SPORTING GOODS 72.00 2,880.00 LTD *PRO PLAYER SUPPLY 83.97 3,358.80 2 NA Charcoal Badger Hooded Sweatshirt 15 ST SCHOOL SPECIALTY INC NB NB #1254 with two color lettering & pant #1277 open bottom no lettering, lettering & sizes to follow when order is placed, no subs fill-ins Y AMERICA TEAM SPORTS 34.00 510.00 RIDDELL ALL AMERICAN 34.45 516.75 DAN CAREYS SPORTING GOODS 38.57 578.55 LTD VARSITY BRANDS HOLDINGS CO 44.00 660.00 INC ROBIN BAUGH 45.00 675.00 *PRO PLAYER SUPPLY 46.95 704.25 3 NA Badger Hooded Sweatshirt #125400 & 10 ST SCHOOL SPECIALTY INC NB NB pant #147800 with two color lettering on sweatshirt & right leg of pant, sizes to follow when order is placed, no subs fill- ins Y AMERICA TEAM SPORTS 42.50 425.00 DAN CAREYS SPORTING GOODS 52.56 525.60 LTD ROBIN BAUGH 53.00 530.00 *PRO PLAYER SUPPLY 53.96 539.60 VARSITY BRANDS HOLDINGS CO 56.00 560.00 INC 4 NA Royal Blue Badger Hooded Sweatshirt 22 ST SCHOOL SPECIALTY INC NB NB #125400 & pant #147800 with "Colonel" "Softball" & "SG" "Softball" on pant in white, sizes to follow when -

The Developing Years 1932-1970

National Park Service Uniforms: The Developing Years 1932-1970 National Park Service National Park Service Uniforms The Developing Years, 1932-1970 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE UNIFORMS The Developing Years 1932-1970 Number 5 By R. Bryce Workman 1998 A Publication of the National Park Service History Collection Office of Library, Archives and Graphics Research Harpers Ferry Center Harpers Ferry, WV TABLE OF CONTENTS nps-uniforms/5/index.htm Last Updated: 01-Apr-2016 http://npshistory.com/publications/nps-uniforms/5/index.htm[8/30/18, 3:05:33 PM] National Park Service Uniforms: The Developing Years 1932-1970 (Introduction) National Park Service National Park Service Uniforms The Developing Years, 1932-1970 INTRODUCTION The first few decades after the founding of America's system of national parks were spent by the men working in those parks first in search of an identity, then after the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916 in ironing out the wrinkles in their new uniform regulations, as well as those of the new bureau. The process of fine tuning the uniform regulations to accommodate the various functions of the park ranger began in the 1930s. Until then there was only one uniform and the main focus seemed to be in trying to differentiate between the officers and the lowly rangers. The former were authorized to have their uniforms made of finer material (Elastique versus heavy wool for the ranger), and extraneous decorations of all kinds were hung on the coat to distinguish one from the other. The ranger's uniform was used for all functions where recognition was desirable: dress; patrol (when the possibility of contact with the public existed), and various other duties, such as firefighting. -

Murphycatalog.Pdf

® Welcome to our Qwick-Ship catalog of Visit www.MurphyRobes.com for our entire GUARANTEED SATISFACTION ready-to-ship items for choirs, pastors, and the collection containing hundreds of items Every item in this catalog is backed by our church - an unbelievable selection of quality available custom made. Qwick-Ship® Guarantee of Satisfaction. If you products in an incredible range of sizes you are not completely satisfied, return it, unused won't find anywhere else. and unworn, within 30 days of receipt for exchange or refund. READY TO SHIP Items in this catalog are available exactly as shown and described in sizes on referenced size chart, ready to ship next business day following receipt of order. Shipping costs vary based on speed. WHITE GLOVE® PACKAGING SERVICE With our exclusive White Glove® Packaging Service, all apparel is placed on a deluxe hanger, individually bagged and packed in a specially designed shipping container to minimize wrinkling at no extra charge. STANDARD SIZING Qwick-Ship® sizing patterns have been carefully developed to fit "average" body types with non-exceptional proportions. Order by size using item specific size charts. EXTRA SAVINGS Qwick-Ship® items are specially priced to offer extra savings over identical custom made items. Savings are shown throughout this catalog on items available custom made. AVAILABLE CUSTOM MADE To order an item in sizes, fabrics, colors or with other details than shown, ask us for assistance with custom made ordering. Allow a minimum of 8 weeks for manufacture and shipment of custom made items. We make every attempt to show fabric colors as accurately as possible. -

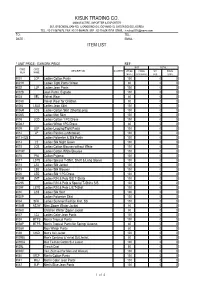

Kisuk Trading Co

KISUK TRADING CO. MANUFACTRE, IMPORTER & EXPORTER 267, GYEONDALSAN-RO, ILSANDONG-GU, GOYANG-SI, GYEONGGI-DO, KOREA TEL : 82-31-9674676, FAX :82-31-9684678, M.P : 82-10-62437758 EMAIL : [email protected] TO : TEL : DATE : EMAIL : ITEM LIST * UNIT PRICE : EXWORK PRICE REF: UNIT TOTAL CODE CODE DESCRIPTION QUANTITY WT(KG PRICE WT PRICE NUM NAME /BALE) (USD/BALE) (KG) (USD) #001 LCP Ladies Cotton Pants 100 0 0 #001H Ladies Tight Pants Winter 80 0 0 #002 LJP Ladies Jean Pants 100 0 0 #002B Jean Pants, B grade 100 0 0 #003 VEL Velvet Wear 80 0 0 #003C Velvet Wear for Children 80 0 0 #006J LBJS Ladies Jean Skirt 100 0 0 #006M LCS Ladies Cotton Skirt (Short&Long) 100 0 0 #006S Ladies Mini Skirt 100 0 0 #008 LCD Ladies Cotton 1 PC Dress 100 0 0 #008-1 Ladies Winter 1PC Dress 80 0 0 #009 LEP Ladies Legging/Tight Pants 100 0 0 #012 LP Ladies Panties (underwear) 100 0 0 #013+028 Ladies Polyester & Silk Pants 100 0 0 #014 LS Ladies Silk Night Gown 100 0 0 #015 LCB Ladies Cotton Blouses without White 100 0 0 #015W Ladies Cotton White Blouses 100 0 0 #016 PAJ Cotton Pyjama 100 0 0 #017 LSTS Ladies Special T-Shirt, Short & Long Sleeve 100 0 0 #018 LSJ Ladies Silk Jacket 100 0 0 #019 LSB Ladies Silk Blouses 100 0 0 #020 LSD Ladies Silk 1 PC Dress 100 0 0 #029M LMT Ladies R/N & Polo S/S T-Shirts 100 0 0 #029S Ladies R/N & Polo & Special T-Shirts S/S 100 0 0 #029F LSTS Ladies R/N & Polo L/S T-Shirt 100 0 0 #030 LSS Ladies Silk Skirt 100 0 0 #030P Ladies Polyester Skirt 100 0 0 #034 SFK Ladies Summer Fashion Knit, SS 100 0 0 #036M AZJW Men Zipper Winter -

Uniform Newsgram 2019 Winter

A Newsletter keeping you up to date on uniform policy and changes Winter 2019-20 Summer 2019 UNIFORM NEWSGRAM Winter Uniform Wear and News In this issue: NAVADMIN 282/19 - NAVADMIN 282/19 NAVADMIN 282/19 Navy Uniform Policy and Uniform Initiative - Gold Star/Next of Kin Lapel Button Update has been released and provides updates on recent Navy uniform - Black Neck Gaiter Optional Wear policy initiatives. - Optional PRT Swimwear - Acoustic Technician CWO Insignia Gold Star Lapel Button (GSLB)/Next of Kin Lapel - Uniform Initiatives Button (NKLB) Optional Wear - NWU Type III: Know Your Uniform The GSLB and NKLB designated for eligible survivors of - Frequently Asked Questions Service Members who lost their lives under designated circumstances are now - ‘Tis the Season: Authorized Outerwear authorized for optional wear with Service Dress and Full Dress uniforms. - Myth Busted: Navy-issued Safety Boots - NWU Type III Fit Guide Black Neck Gaiter Optional Wear - New Uniform Mandatory Wear Dates NAVADMIN 282/19 authorized the optional wear of a Black Neck Gaiter during extreme cold weather conditions as promulgated by Regional Commanders ashore and as prescribed by commanding officers afloat. When authorized, it may be worn with the following cold weather outer garments only: Cold Weather Parka, NWU Type II/III Parka, Peacoat, Reefer, and All Weather Coat. Optional Physical Readiness Test (PRT) Swimwear Optional wear of full body swimwear is authorized for Sailors who elect to swim during their semi-annual PRT. Optional swimwear will be navy blue or black in color, conservative in design and appearance and must not prohibit the swimmer from swimming freely. -

May 8, 1928. 1,668,745 F

May 8, 1928. 1,668,745 F. W., TULLY COLLAR AND CUFF Filed Sept. 2, 192l Patented May 8, 1928. 1,668,745 UNITED STATES PATENT of FICE. FRANCIS W. TULLY, OF BROOKLINE, MASSACEUSETTS, COLLAR AND CUFF. Application filed September 2, 1921. serial No. 497,891. This invention relates to collars and cuffs, damage by wear during laundry operations which may be of the kind attached to the is excessive, the average garment being ca garment with which they are worn per pable of being worn only a few times before manently by sewing, or of the kind attached the cleansing operation destroys it. replaceably by buttons or other fasteners, The imitation-fabric collars and cuffs are 60 and to the method of making them. not really deceptive, and their use is associ The prior art as heretofore practised has ated in the public mind with careless per provided garments of the class referred to sonal habits. intended to be worn in a soft state without 0 It is therefore highly desirable satis laundry starching; garments intended to be factorily to replace the limp soft collar and 65 starched; and imitation garments of the cuff and the heavily starched stiff collar and stiff type, made of a fabric and additions of cuff with textile-fabric or genuine articles of one sort or another, such as heavy coatings this sort which shall be cleanly, of good ap 5 of white pigments and binders of celluloid, perance and not subject to rapid damage in rubber and other hard calendered substances, use, and capable of being refreshed in a 70 which sometimes have been embossed to take simpler way than the laundry operations re the appearance of the cloth they are sup quired for a stiff collar.