The Feather Wars and Theodore Roosevelt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness on the Edge: a History of Everglades National Park

Wilderness on the Edge: A History of Everglades National Park Robert W Blythe Chicago, Illinois 2017 Prepared under the National Park Service/Organization of American Historians cooperative agreement Table of Contents List of Figures iii Preface xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Acronyms Used in Footnotes xv Chapter 1: The Everglades to the 1920s 1 Chapter 2: Early Conservation Efforts in the Everglades 40 Chapter 3: The Movement for a National Park in the Everglades 62 Chapter 4: The Long and Winding Road to Park Establishment 92 Chapter 5: First a Wildlife Refuge, Then a National Park 131 Chapter 6: Land Acquisition 150 Chapter 7: Developing the Park 176 Chapter 8: The Water Needs of a Wetland Park: From Establishment (1947) to Congress’s Water Guarantee (1970) 213 Chapter 9: Water Issues, 1970 to 1992: The Rise of Environmentalism and the Path to the Restudy of the C&SF Project 237 Chapter 10: Wilderness Values and Wilderness Designations 270 Chapter 11: Park Science 288 Chapter 12: Wildlife, Native Plants, and Endangered Species 309 Chapter 13: Marine Fisheries, Fisheries Management, and Florida Bay 353 Chapter 14: Control of Invasive Species and Native Pests 373 Chapter 15: Wildland Fire 398 Chapter 16: Hurricanes and Storms 416 Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources 430 Chapter 18: Museum Collection and Library 449 Chapter 19: Relationships with Cultural Communities 466 Chapter 20: Interpretive and Educational Programs 492 Chapter 21: Resource and Visitor Protection 526 Chapter 22: Relationships with the Military -

(PHOENICOPTERUS RUBER) in SOUTHERN FLORIDA. Steven M

STATUS, TRENDS, IMMIGRATION AND HABITAT USE OF AMERICAN FLAMINGOS (PHOENICOPTERUS RUBER) IN SOUTHERN FLORIDA. Steven M. Whitfield,1 Peter Frezza,2 Frank N. Ridgley,1 Anne Mauro,3 Judd M. Patterson,4 AntonioPernas,5 Michelle Davis6 and Jerome J. Lorenz2 1 Zoo Miami, Conservation and Research Department, Miami, Florida 2 Everglades Science Center, Audubon Florida, Tavernier, Florida 3 Rookery Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve, Naples, Florida 4 National Park Service South Florida/Caribbean Network, Palmetto Bay, Florida 5 Big Cypress National Preserve, Ochopee, Florida 6Cape Florida Banding Station Florida’s Most Iconic Bird? Flamingo sighted in Florida Keys – A newsworthy event? Capture SUCCESSFUL – Named “Conchy” Historic Accounts of Flamingos in Florida (1827-1902) Year Location Region Number Reference 1827 Anclote Keys Tampa Bay 3 McCall 1968 1832 Indain Key Florida Keys Large Flock Audubon 1938 1832 Key West Florida Keys "a great number" Audubon 1938 1857 Key West Florida Keys >500 Wudermann 1860 Everglades-10,000 "tens of thousands " mixed 1880 Marco Island Ward 1914 Islands flock with Roseate Spoonbills Everglades-10,000 1886 Marco Island 5 Ward 1914 Islands 1885 Upper Cross Bank Florida Bay 2 large flocks Pierce 1962 Everglades-10,000 Winter 1884-85 Caxambus Bay 7 Ingraham 1893 Islands Winter 1884-85 East of Cape Sable Florida Bay 31 Ingraham 1893 Winter 1884-85 Garfield or Snake Bights Florida Bay >2500 Ingraham 1893 Winter 1885-86 Garfield or Snake Bights Florida Bay 1000 Ingraham 1893 Winter 1886-87* Garfield or Snake Bights Florida Bay No Estimate Ingraham 1893 1890 Garfield or Snake Bights Florida Bay >1000 (50 juv) Scott 1890 1902 Garfield or Snake Bights Florida Bay 500-1000 Howe 1902 Single feathers were used or the whole back skin of the bird with its valuable breeding plumes were fashioned into hats. -

Long-Term Population Trends of Colonial Wading Birds in the Southern United States: the Impact of Crayfish Aquaculture on Louisiana Populations

The Auk 112(3):613-632, 1995 LONG-TERM POPULATION TRENDS OF COLONIAL WADING BIRDS IN THE SOUTHERN UNITED STATES: THE IMPACT OF CRAYFISH AQUACULTURE ON LOUISIANA POPULATIONS BRUCE E. FLEURY AND THOMAS W. SHERRY Departmentof Ecology,Evolution, and Organismal Biology, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana 70118, USA Al•sTl•C•r.--Long-termpopulation dynamics of colonialwading birds (Ciconiiformes) were examinedusing data from Audubon ChristmasBird Counts(CBC, 1949-1988)and Breeding Bird Surveys(BBS, 1966-1989). Winter populationsof Louisianawading birds increased dramaticallyover the 40-yearperiod, with the sharpestincreases occurring during the last 20 years.Several species populations grew exponentiallyfrom 1968to 1988.High overall positivecovariance was found in the abundanceof the variousspecies over time, and cluster analysisshowed that the specieswith similardietary requirements and foraginghabits cov- ariedmost strongly and positivelywith eachother. Trend analysis of CBCand BBSdata from 1966-1989and 1980-1989showed a closecorrespondence between CBC and BBStrends in Louisiana.Most speciesincreased in Louisianaat the sametime as they declined in Florida andTexas. Several factors might explain increases in populationsof wadingbirds in Louisiana, includinglong-term recovery from the effectsof humanexploitation, expansion of breeding populationsin more northern states,changes in weather,recovery from DDT and similar pesticides,and regionalmovements due to habitatloss in other coastalstates. These hypoth- esesare not mutuallyexclusive -

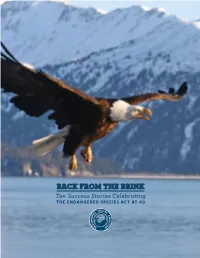

Back from the Brink Ten Success Stories Celebrating the Endangered Species Act at 40 Introduction Acknowledgements

BACK FROM THE BRINK Ten Success Stories Celebrating THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT AT 40 INTRODUCTION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Success. We are constantly bombarded with messages about the to the Endangered Species Act, stories like these can be found in importance of success and how to achieve it. Search for a book every state across the country as imperiled animals, plants, birds, and about success on Amazon, and you’ll get not only the Seven Habits fish are stabilizing and rebuilding healthy populations. Indeed, most of Highly Effective People, but also more than 170,000 other books endangered species are on track with established recovery plans, on how to be successful at work, in friendships and relationships, and some are even reaching population goals ahead of their targeted and way more. Clearly, we place an incredible value on success. schedules. In this report, you will find ten success stories that are among the most compelling in the nation. But when it comes to protecting wildlife and wild lands, how do we define success? To some of us, the answer is obvious. But in On the 40th anniversary of the Act, it is time to celebrate our journey our highly charged political atmosphere, wildlife opponents seek as we have brought one species after another back from the brink of to narrow the definition of success in a concerted effort to weaken extinction. Passing this moral and noble law was the first step along a wildlife protections. Their thinking goes that, if they can convince new path for the United States. We were once a nation that believed us that our conservation efforts have not been successful, we will that rivers were meant to be dammed, forests to be completely clear cut, support getting rid of existing protections. -

"The Cruise of the Bonton" :Tequesta

Ornithology of "The Cruise of the Bonton" By William B. Robertson, Jr. The Bonton's cruise having been undertaken for the specific purpose of collecting plumes and bird specimens, it is not surprising that observations of birds comprise the most interesting and significant biological data in the narrative. Although the narrator uses some common names that are no longer current, the specific identity of most of the birds he mentions is plain. Only the few referred to by such general terms as "duck", "gull", and "heron" are not identifiable. The narrative's general agreement with ornithological information from other contemporary sources provides ample evidence that Pierce was a keen and accurate observer. It is likely, however, that some of the more detailed comments, such as those concerning the Reddish Egret, draw heavily upon the opinions of Chevelier. In all, 42 species of birds can be recognized from "The Cruise of the Bonton". The list below pairs the present technical and vernacular names1 of these species with the names used in the narrative. Records of special interest are briefly annotated. Figures in parenthesis are the total number of each species killed during the trip. WHITE PELICAN (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) "white pelican". The observation-near Pavilion Key, Monroe Co., about 14 June 1885- provides one of the earliest definite records of the summering of this species in southern Florida. As is now well known, small numbers of non-breeding individuals regularly summer along the Gulf Coast. BROWN PELICAN (Pelecanus occidentalis) "Pelican" (284). DOUBLE-CRESTED CORMORANT (Phalacrocorax auritus) "cormorant" (193). ANHINGA (Anhinga anhinga) "water turkey" (1). -

Florida Audubon Assembly Happens Once a Year! All Marion Audubon Society Members Are Invited to Attend This Assembly

MARION AUDUBON SOCIE TY MARION AUDUBON SOCIETY OUR RICH, NATURAL HERITAGE SUTAINS OUR F UTURE found shelter from the sun under WHATS IN A a sparse canopy of oak and AUDUBON IN NAME? understory of large shrubs. This MARION COUNTY shelter provided ample habitat By Judy Greenberg November 2016 marks During my vacation to San for a variety of nesting and song the Diego in August, I discovered birds. Hummingbirds and 30th Anniversary for the new places, new friends and the butterflies darted among name, San Diego Audubon. flowering native plants in the San Diego County is rocks. The birds moved easily Marion Audubon geographically large like Marion around the habitat in a Society. County, boasting diverse natural spectacular display of agility. I The original objectives areas: swamp marshes, arid observed the Western Scrub adopted by the Jay, and deserts and organization have The mission of the National hardwood committed to Audubon Society is to conserve and changed very little forests. I visited make time restore natural ecosystems by since 1986. special places this year to focusing on birds, other wildlife, and How the organization attend a Jay with names their habitats for the benefit of goes about foreign to me: humanity and the earth’s biological Watch accomplishing its Anza Borrego diversity. Training with Desert State Park, Cuyamaca Marianne Korosy. Stellar Jays, objectives changes State Park and San Elijo Lagoon. Acorn Woodpecker, sparrows with the times to better Overlooking a valley of dry, and warblers were abundant for meet the needs of the gritty brown soil, mounds of rock, my birding pleasure. -

BIG SIT! Report the SAS Team, Seminole Sitters, Competed in the 19Th Annual Big SIT! on Sunday October 12 at Lake Jesup Park

The mission of the Seminole Audubon Society is to promote awareness and protection of the plants and animals in the St. Johns River basin in order to sustain the beneficial coexistence of nature and humans. November - December 2014 A Publication of Seminole Audubon Society BIG SIT! Report The SAS team, Seminole Sitters, competed in the 19th annual Big SIT! on Sunday October 12 at Lake Jesup Park. The Big SIT! is a species count described by its sponsor, BirdWatcher’s Digest, as “Birding’s Most Sedentary Event.” Unlike most bird counts that involve traveling to various spots along a route or within an area, the Big SIT! is done from a 17’ circle. The 2014 Big Sit! consisted of 184 competing circles in 50 states and countries. Our team included sixteen birders this year. Many arrived before the sun, but not before the boaters. The location where we have erected the canopy in previous years was under water forcing us to adjust our location slightly. New species for our Big SIT! count included least bittern and purple gallinules. We were happy nearly as many species. to see American bitterns, king rails, our friendly limpkins, and painted buntings. Although many We had stiff competition this year with nine count of our regularly-seen species were absent this year, circles competing for the highest count in Florida. our final count was 53 species. We extend our The Celery Fields Forever team of Sarasota won the special thanks once again to Paul Hueber, without whose expertise we would not have tallied See BIG SIT! on page 13 The printing and mailing of this newsletter is made possible in part by the generous donations of Bob and Inez Parsell and ACE Hardware stores in Sanford, Longwood, Casselberry, and Oviedo. -

Florida Field Naturalist Published by the Florida Ornithological Society

Florida Field Naturalist PUBLISHED BY THE FLORIDA ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY VOL. 41, NO. 2 MAY 2013 PAGES 29-69 Florida Field Naturalist 41(2):29-41, 2013. REDDISH EGRET (Egretta rufescens) NESTING IN CLEARWATER HARBOR AND ST. JOSEPH SOUND, PINELLAS COUNTY, AND CRYSTAL BAY, CITRUS COUNTY, FLORIDA FROM 1991 TO 2011 ANN B. HODGSON1 AND ANN F. PAUL Florida Coastal Islands Sanctuaries, Audubon Florida, 410 South Ware Boulevard, Suite 702, Tampa, Florida 33619 1Current address: Resource Designs Inc., Natural Resource Research & Planning, P. O. Box 311, Brooksville, Florida 34605 Abstract.—Through the 1880s, Reddish Egrets (Egretta rufescens) occurred through- out Florida, and commonly among coastal colonial waterbird colonies in Pinellas County north to the St. Martins Keys in Citrus County. By around 1910, plume hunting and the associated disturbance at nesting colonies extirpated Florida’s breeding population of Reddish Egrets, and nesting egrets were not found again in southern Florida until 1938. The first nesting record on Florida’s central Gulf coast since 1890 occurred at the Alafia Bank Bird Sanctuary in Hillsborough Bay in 1974. Egrets slowly reappeared at suitable estuarine nesting sites throughout Tampa Bay and the nearby coast, and solitary pairs or small breeding groups now nest on at least 15 colony islands stretching from Three Rooker Island State Preserve (northern Pinellas County) south to Hemp Key in Pine Island Sound (Charlotte County), with the largest nesting concentration persisting at the Alafia Bank Bird Sanctuary. In Clearwater Harbor and St. Joseph Sound, egrets nested on eight dredged spoil-material islands from 1991 to 2011 (annual colony size –x = 0.01-2.8 nests, SD = 0.4-4.5, N ≤ 21 years). -

Wading Bird Report 2 Pager

2019 Tampa Bay Region Wading Bird Report Stepping up protection efforts to combat increased disturbance. Each nesting season since 1934, Audubon's quantity in estuarine systems, and harmful dedicated biologists have patrolled the algal blooms have all impacted the success of mangrove islands of the Tampa Bay region to these sensitive species. protect and later survey the region's iconic wading bird population. Since documenting Because of our observations, we've been able these species pushed to the brink of to successfully lobby for increased protections extinction by plume hunting in the early at these vulnerable, essential nesting sites. Not 1900s, Audubon has tracked the recovery of only should this help blunt population Roseate Spoonbills, Wood Storks, Reddish declines, but we have even documented Egrets, Little Blue Herons, Brown Pelicans higher numbers of fledged chicks for some and more, as well as used our data to species in recent years. document new threats to their survival. Give today: In recent decades, disturbance by boaters, fl.audubon.org/fcis declining water quality and freshwater Roseate Spoonbills. Photo: Cynthia Hansen. Reddish Egret. Photo: David Pugsley. Wood Stork. Photo: Trudy Walden. Total Wading Bird Nesting Pairs from 1984 through 2019 While total nesting pairs of all species had a hopeful uptick in 2019, individual species have different outlooks. Roseate Spoonbill populations have been fairly stable in the region since 2011, and Brown Pelicans rallied in 2019, likely in response to the Sanctuary Manager Mark Rachal recovery of their prey base after the devastating works to remove fishing line from a Brown Pelican. harmful algal blooms of 2018. -

The Egrets Were Doomed. Everyone Agreed on That. the New Wealth

The egrets were doomed. Everyone agreed on that. The new wealth created by the conquest of America had in turn, created a large middle class whose women demanded the finest fashions - including the lovely plumes of the egret to adorn their enormous collec tion ofhats. Since the birds developed the plumes only during the breeding by Elaine Radford season, collecting the feathers meant Metairie, Louisiana killing the adults and leaving eggs or chicks to die. Unable to reproduce, the egrets faced almost certain extinction. Continued onpage 26 More than 20} 000families ofherons} mostly the white varieties known as egrets} are Even ifyou Jre badatjudgingsizes) the com raised atAveryIsland eachyear: mon egret is easily distinguishedfrom the snowy because the larger common egret has blackfeet. The snowyhas brightyellowfeet on the endofits long} black legs. A closer view ofone ofthe nestingplatformsshows many babyandjuvenile egrets. A great egret(Egretta alba)fishing. 24 Augu t/September 1987 ERECT EASY WIRE COo KNCo 6912 Tujunga Avenue North Hollywood, CA 91605 (818) 762-7966 Erect Easy Wire Panels are so sturdy that they are self-supporting - NO FRAMEWORK is required. Assemble your aviary kit in just minutes or a few hours. This new innovation in aviaries has provided thousands of people with beautiful, secure and functional aviaries. Whether for one or for a hundred flights. you will like our style and price .. Some Sample Sizes and Prices.... We can design and build virtually any size and shape. P~ease call for quotes. A Clip pliers is the only tool needed to quickly WALK IN AVIARIES install these units. -

Birds of a Feather Died Together: the Fight to Protect Florida’S Birds R

Birds of a Feather Died Together: The Fight to Protect Florida’s Birds R. Boyd Murphree , April 21, 2017 Portrait of Monroe County Game Warden Guy M. Bradley Courtesy of Florida Memory I t is important to note that the work of protecting the environment has often been difficult, depressing, and even deadly. These aspects of environmental history came together in turn of the cen tury Florida with the killing of Guy Bradley, a game warden who had fought to protect Florida birds from the ravages of plume bird hunters. Called “America’s First Martyr to Environmentalism,” Bradley was one of a handful of people who were willing to put their lives on the line to protect endangered species (McIver, xi ). His actions were part of a nascent bird conservation movement headed by the newly formed Audubon Society and President Theodore Roosevelt, whose lifelong love of nature, especially of bird s, drove him to create the nation’s first bird reserves as well as a multitude of national forests, game preserves, national parks, and national monuments. Florida newspapers covered Bradley’s death and many other episodes in this early environmental strug gle. Killing birds for their decorative feathers was an ag e old practice, but it did not become an industry until the latter half of the nineteenth century, when the extraordinary growth of the American economy during the Gilded Age combined with a fashion craze among wealthier women for hats adorned with colorful bird plumes created a profitable market for the plumes of egrets and herons. By the late nineteenth century the last sanctuaries of these beautiful birds were the c oastal wetlands and the Everglades of South Florida. -

Outside Front Cover Inside Front Cover

Outside Front Cover Inside Front Cover what is a wading bird? Selecting the most graceful bird group To be sure, other bird groups possess within the entire class (Aves) of birds – similar combinations of long legs, arguably the most graceful of all animal long necks, and long bills. Both classes – is a difficult task. By the same the cranes (order Gruiformes) and token, however, it is equally difficult certain shorebirds (i.e. stilts, curlews, to deny the top spot to the exquisitely- godwits, and some sandpipers; order sculpted, long-legged, long-necked, Charadriiformes) are prime examples. long-billed wading birds. But the cranes are more genetically allied with the rails, and the shorebirds possess Biologically, the bird group known bloodlines which are closer to the gulls Ronnie Gaubert, Photographer_Tricolored Heron as the “wading birds” is comprised and terns. David Chauvin, Photographer_Cattle Egret of those species belonging to the families Ardeidae (bitterns, herons, Seventeen species of wading birds egrets), Threskiornithidae (ibises and regularly occur in Louisiana. These spoonbills), Ciconiidae (Wood Stork), include the American Bittern, Least and Phoenicopteridae (flamingoes), all Bittern, Great Blue Heron, Great Egret, of which possess proportionately long Snowy Egret, Reddish Egret, Tricolored legs, long necks, and long bills adapted Heron, Little Blue Heron, Cattle Egret, for wading and feeding in relatively Green Heron, Black-crowned Night- shallow water; and all of which belong Heron, Yellow-crowned Night-Heron, to the