The Victorian Soldier in Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Congo Basin to the Highlands of Ethiopia

From the Congo Basin to the Highlands of Ethiopia From the Congo Basin to the Highlands of Ethiopia by Steve Christenson Safari Press This book is dedicated to my wife, Sheryl, Without you, none of this would have been possible. FROM THE CONGO BASIN TO THE HIGHLANDS OF ETHIOPIA © 2013 by Steve Christenson. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher. The trademark Safari Press ® is registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and with government trademark and patent offices in other countries. Christenson, Steve First edition Safari Press 2013, Long Beach, California ISBN 978-1-57157-390-2 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2011942114 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in China Readers wishing to receive the Safari Press catalog, featuring many fine books on big-game hunting, wingshooting, and sporting firearms, should write to Safari Press, P.O. Box 3095, Long Beach, CA 90803, USA. Tel: (714) 894- 9080 or visit our Web site at www.safaripress.com Table of Contents Foreword by Tommy Caruthers ........................................................................................................................................vii Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................................ix Part I Egypt and Sudan Chapter 1 The Warrior Priests ................................................................................................................................1 -

Battlefields

Nicole C. Vosseler – Beyond the Nile Battlefields Flight of the Khalifa after the Battle of Omdurman, 1898 Robert George Talbot Kelly, ca. 1900 Just like the Crimean War, one of the historical backgrounds in Beneath the Saffron Moon and briefly mentioned in Beyond the Nile, the Mahdist Revolt has hardly left any traces in the consciousness of the Western world - except in that of the British, since Great Britain was the only European power in- volved. If the name of the Mahdi is ever mentioned, it is mostly in relation to the sec- Mohammed Ahmad, the Mahdi ond campaign of 1896-1899 – and then only referring to one lieutenant who took part in this campaign und who later on became famous by his political activities, by premier minister and last but not least by his eccentric character: Winston S. Churchill. This second campaign though was an immediate consequence of the first campaign from 1881 to 1885, the historical backdrop of the novel. Not all regiments dispatched to Egypt and Sudan were involved in every battle, and therefore the depic- tion of the revolt in the novel is guided by the perspective of the Royal Sussex, the regiment of Jeremy, Stephen, Leonard, Royston, and Simon. © Nicole C. Vosseler 1 A regiment that, after the suppression of the ‘Urabi Revolt in Egypt and before its arrival at Khartoum, took part in three battles; one of them is only sketched briefly in the novel, while the other two are an extensive part of the storyline. Battle of El-Teb: February 29th, 1884 Strictly speaking, it should be called “the second Battle of El-Teb”, since this battle occurred as revenge, on the same site where on February 4th the year before, an array of 3,500 Egyptian soldiers under General Valentine Baker was almost completely erased by Osman Digna’s men. -

2-Reem-Phd Thesis-Draft-21-2020

Delft University of Technology Optimizing the operation of a multiple reservoir system in the eastern nile basin considering water and sediment fluxes Digna, Reem Publication date 2020 Document Version Final published version Citation (APA) Digna, R. (2020). Optimizing the operation of a multiple reservoir system in the eastern nile basin considering water and sediment fluxes. CRC Press / Balkema. Important note To cite this publication, please use the final published version (if applicable). Please check the document version above. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download, forward or distribute the text or part of it, without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license such as Creative Commons. Takedown policy Please contact us and provide details if you believe this document breaches copyrights. We will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. This work is downloaded from Delft University of Technology. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to a maximum of 10. OPTIMIZING THE OPERATION OF A MULTIPLE RESERVOIR SYSTEM IN THE EASTERN NILE BASIN CONSIDERING WATER AND SEDIMENT FLUXES Reem Fikri Mohamed Osman Digna OPTIMIZING THE OPERATION OF A MULTIPLE RESERVOIR SYSTEM IN THE EASTERN NILE BASIN CONSIDERING WATER AND SEDIMENT FLUXES DISSERTATION Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the Board for Doctorates of Delft University of Technology and of the Academic Board of the IHE Delft Institute for Water Education for the Degree of DOCTOR to be defended in public on Tuesday 26 May 2020, at 15:00 hours in Delft, the Netherlands by Reem Fikri Mohamed Osman DIGNA Master of Science in Water Resources Engineering, University of Khartoum born in Khartoum, Sudan iii This dissertation has been approved by the promotors: Prof.dr.ir. -

Jaroslav Valkoun the Sudanese Life of General Charles George Gordon1

Anton Prokesch von Osten… | Miroslav Šedivý 48 | 49 He in no way gained the general esteem of his colleagues by assentation as claimed by Jaroslav Valkoun Hammer-Purgstall but, on the contrary, by raising arguments even in contradiction with the opinion prevailing at the Viennese Chancellery at the time, as happened in 1832. The validity of his opinions considerably improved his position and increased Me- tternich’s respect. Consequently, though more well-disposed towards Mohammed Ali than the Austrian chancellor himself, Prokesch continued to play the role of Metterni- ch’s adviser in the following years, and he did so either by his written comments to Laurin’s reports or through personal meetings with the chancellor in Vienna. With his two memoirs from late 1833 Prokesch also significantly influenced Metternich’s Egyp- tian policy for several years to come. Prokesch’s considerable reputation was so high that it survived Metternich’s fall in March 1848 and later brought him to the diplomatic post in Constantinople where, as mentioned above, he represented the Austrian and later the Austro-Hungarian Empire from 1855 to 1871. References BEER, Adolf (1883): Die orientalische Politik Österreichs seit 1773. Prag, Leipzig: E. Tempsky und G. Freytag. BERTSCH, Daniel (2005): Anton Prokesch von Osten (1795–1876). Ein Diplomat Österreichs in Athen und an der Hohen Pforte. Beiträge zur Wahrnehmung des Orients im Europa des 19. Jahrhunderts. München: R. Ol- The Sudanese life of General denbourg Verlag. 1 FICHTNER, Paula Sutter (2008): Terror and Toleration. The Habsburg Empire Confronts Islam, 1526–1850. Charles George Gordon London: Reaktion Books. -

The Mahdiyya, Bib

BIBLIOGRAPHIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE MAHDIST STATE IN THE SUDAN (1881-1898) AHMED IBRAHIM ABU SHOUK The Sudanese Mahdiyya was a movement of social, economic and political protest, launched in 1881 by Mu˛ammad A˛mad b. fiAbd Allh (later Mu˛ammad al- Mahdı) against the Turco-Egyptian imperialists who had ruled the Sudan since 1821. After four years of struggle the Mahdist rebels overthrew the Turco-Egyptian administration and established their own ‘Islamic and national’ government with its capital in Omdurman. Thus from 1885 the Mahdist regime maintained sovereignty and control over the Sudanese territories until its existence was terminated by the Anglo-Egyptian imperial forces in 1898. The purpose of this article is first to give a brief survey of the primary sources of Mahdist history, secondly to trace the development of Mahdist studies in the Sudan and abroad, and finally to present a detailed bibliography of the history of the Mahdist revolution and state, with special reference to published sources (primary and secondary) and conference papers. Bibliographic overview The seventeen years of Mahdist rule in the Sudan produced a large number of published and unpublished primary textual sources on the history of the revolution and its state. Contri- butions from ‘Mahdist intellectuals’ in the Sudan were products of the state written in defence of the ideals of Mahdist ideology and the achievements of the Mahdi and his successor, the Khalifa fiAbdallhi. The Mahdi himself left a Sudanic Africa, 10, 1999, 133-168 134 AHMED IBRAHIM ABU SHOUK corpus of literary works, which manifest his own teachings, proclamations, sermons and judgements issued on various occasions. -

The University of Hull Suakin and Its Fishermen

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL SUAKIN AND ITS FISHERMEN: A STUDY OF ECONOMIC ACTIVITIES AND ETHNIC GROUPINGS IN A SUDANESE PORT being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Eric George Kentley, B. A. February 1988 ,ý ft> 'ý' : n ý' ate Summary Summary of Thesis submitted for Ph. D. degree by E. C. Kentley on Suakin and its Fishermen: a study of economic activities and ethni_ groupings in a Sudanese port This study examines the role that ethnic identity plays in economic activities within the context of Suakin, with particular T reference to fishing. Chapter One defines the. context physically and. to some extent culturally. It begins with a discussion of the boats used by the fishermen, which suggests that in this respect at least Suakin is culturally more akin to the Middle East, or "dhow world", than to the interior of Sudan. The environment in which these boats operate and the appearance of the town is then described. This appearance and the presence of the current population is accounted for in Chapter Two, which relates the history of the town and its people. In Chapter Three, the concept of "ethnic grouping" is developed from earlier concepts in order to classify the present population. The concept is applied in Chapter Four, where there is also an examination of the activities, organisation and sizes of these groupings. Chapters Five and Six give a detailed account of the fishing industry in Suakin, including an assessment of a development project aimed at improving productivity and an elucidation of two "universal" methods of profit distribution by share allocation. -

Geopolitical Significance of Suakin on Anglo-Turkish Rivalry During the 19Th Century

GEOPOLITICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF SUAKIN ON ANGLO-TURKISH RIVALRY DURING THE 19TH CENTURY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY HAMZA HAŞIL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF MIDDLE EAST STUDIES SEPTEMBER 2019 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar Kondakçı Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Assist Prof. Dr. Derya Göçer Akder Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Ömer Turan Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Ahmet Uysal (İstanbul Uni., Uİ) Prof. Dr. Ömer Turan (METU, HIST) Assist Prof. Dr. Bahar Gürsel (METU, HIST) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last Name : Hamza Haşıl Signature : iii ABSTRACT GEOPOLITICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF SUAKIN ON ANGLO-TURKISH RIVALRY DURING THE 19TH CENTURY Haşıl, Hamza M.Sc., Department of Middle East Studies Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ömer Turan September 2019, 98 pages This thesis argues that the geopolitical significance of Suakin in the Red Sea in the 19th century can be explained through the Anglo-Turkish rivalry. -

An Annotated Bibliography of South Sudan

UN Photo by Staton Winter ~ Contents ~ PREFACE ........................................................................................................................... 3 HISTORICAL NOTE ........................................................................................................ 3 BIBLIOGRAPHIES AND GENERAL REFERENCES .................................................... 5 ETHNOGRAPHY AND SOCIAL CUSTOMS ................................................................ 7 RELIGION ....................................................................................................................... 11 GEOGRAPHY AND MAPS ............................................................................................ 12 HISTORY ......................................................................................................................... 14 LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS ............................................................................... 22 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT ................................................................................. 23 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ........................................................... 38 SELECTED INTERNET SOURCES .............................................................................. 45 SOUTH SUDAN POLITICAL EPHEMERA .................................................................. 46 INDEX .............................................................................................................................. 62 2 Preface This finding aid on the new -

The Victorian Soldier

CHAPTER EIGHT Reconquering the Sudan After the costly failure of the Gordon relief expedition, successive British governments retained only a small army of occupation in Egypt and withdrew forces from the southern frontier, the defence of which was left increasingly to the Egyptian Army. The latter was reformed and trained by a cadre of British officers and NCOs and was periodi- cally supported by British units, notably a squadron of the 20th Hus- sars at the battle of Toski (13 August 1889) and in engagements with Osman Digna’s forces near Suakin. British units were even more prominent in the Sudanese campaigns of the late 1890s; the 1/North Staffordshires served in the Dongola campaign of 1896 and another eight battalions, supported by the 21st Lancers, two batteries of artillery, a machine-gun battery and a flotilla of gunboats served in the Anglo-Egyptian army at Omdurman (2 September 1898). As all these campaigns involved protracted journeys and tedious days spent in bar- racks or under canvas, soldiers kept diaries, drew sketches, and took numerous photographs.1 They were also prolific correspondents, and, in some cases, wrote campaign histories based partially on their first- hand experience.2 They explained how the logistic problems of operat- ing in the Sudan were overcome and how an Anglo-Egyptian army defeated the forces of the Khalifa. Some of these letters have been reproduced,3 others have embellished well-known accounts of the campaign, particularly those commemorating the centenary of the battle of Omdurman;4 but the surviving correspondence is even more voluminous than these sources suggest. -

The Eastern Front and the Struggle Against Marginalization

3 The Eastern Front and the Struggle against Marginalization By John Young Copyright The Small Arms Survey Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey The Small Arms Survey is an independent research project located at the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, Switzerland. It serves © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International Studies, Geneva 2007 as the principal source of public information on all aspects of small arms and First published in May 2007 as a resource centre for governments, policy-makers, researchers, and activ- ists. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior Established in 1999, the project is supported by the Swiss Federal Depart- permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by ment of Foreign Affairs, and by contributions from the Governments of Bel- law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- gium, Canada, Finland, France, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should United Kingdom. The Survey is also grateful for past and current project-spe- be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. cific support received from Australia, Denmark, and New Zealand. Further Small Arms Survey funding has been provided by the United Nations Development Programme, Graduate Institute of International Studies the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research, the Geneva 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland International Academic Network, and the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining. -

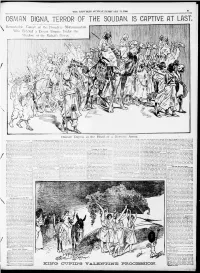

Osman Digna, Captive

TTIE "REPUBLIC: SUNDAY. FEP.TCUATCY 11, IflOO. OSMAN DIGNA, i RROR OF THE SOUDAN, IS CAPTIVE AT LAST. Remarkable Career of the Proselyte Mohamme Who Erected a Desert Empire Under the Shadow of the Mahdfs Power. ' I i :'c-l- ml m !W,!':i "j i'ili'TlllillllllllllPlllflllP Or W, i!'i,!ii ii"''i .,; . Miii'TiTFTMrnMlMi vw Kl MPOT liy if Osman Digma at the Head ol a Dervish Army. army ctptured. It a. band of slaves In this fight. He fell back, Dur-nab- y "bel- policy coniempla'eil tho bt.iiding been slain and his whole a having by sending Gen- With IJaker and Colonel Tho Potidarcae crept up beneath the British svniTri::. For. the sitnday itcrrui-i- underrated the foe t!m. farha had really won a to Darah with about I.0n) men, and won a army to guide General Graham ar- thus afforded They Fpranc upon :! of a railway from Stiakin to Berhr. Pefere turned out that Osman Osman captured! eral Graham's against him. Ilefote hltn. ter s sent out Disna eloign be out ho rcstl!-herde- virto-v- . Ho aroc from the dead on June IS. victory over the Amaha tribesmen How tlio of the Soudan must the Englishman could take the field Tokor rived at El Teb in four hours He hai English rnnl:s and boat tlicm bark. The the culd eirritsl upon Kitch- bis UtJis ! appeared before Tamal check him. Next he returned hand-to-han- had to swept from the desert. 1'51 On that day he f have rolled white eyes whoa that news had fallen. -

Royal Norfolk Regimental Museum Market Avenue, Norwich

Royal Norfolk Regimental Museum Market Avenue, Norwich Contact details: 01603 493650 [email protected] Website: https://www.royalnorfolkregimentalmuseum.org.uk Baggage and Belonging Catalogue 2020 Museum Royal Norfolk Regimental Museum Accession Number NWHRM:1471.1 Categories Arms and armour Object name Helmet Description Helmet, possibly of British origin, described as being ‘collected’ by the 9th (East Norfolk) Regiment during the Second Anglo-Afghan War, 1878- 80, Afghanistan Physical description Helmet with peak and neck guard. The top mount likely featured a plume. Both sides are decorated with lion's heads which would have held a loop for the chinstrap which is missing. The front features a central badge, featuring script (possibly Dari or Pashto) surrounded by ornate brass-work. It is likely that this is an Afghan adaptation of a British ‘Albert Pattern’ cavalry helmet. Names associated 9th (East Norfolk) Regiment Other associations Afghanistan Second Anglo-Afghan War © Royal Norfolk Regimental Museum Baggage and Belonging Catalogue 2020 Museum Royal Norfolk Regimental Museum Accession Number NWHRM:1471.2 Categories Arms and armour Object name Helmet Description Helmet, possibly of British origin, described as being ‘collected’ by the 9th (East Norfolk) Regiment during the Second Anglo-Afghan War, 1878- 80, Afghanistan Physical description Brass helmet with peak and neck guard. Each side is decorated with a lion's head which would have held a loop for the chinstrap which is missing. The front features a central badge with a lion's head encircled with leaves. It is likely that this is an Afghan adaptation of a British ‘Albert Pattern’ cavalry helmet.