The University of Hull Suakin and Its Fishermen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Congo Basin to the Highlands of Ethiopia

From the Congo Basin to the Highlands of Ethiopia From the Congo Basin to the Highlands of Ethiopia by Steve Christenson Safari Press This book is dedicated to my wife, Sheryl, Without you, none of this would have been possible. FROM THE CONGO BASIN TO THE HIGHLANDS OF ETHIOPIA © 2013 by Steve Christenson. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher. The trademark Safari Press ® is registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and with government trademark and patent offices in other countries. Christenson, Steve First edition Safari Press 2013, Long Beach, California ISBN 978-1-57157-390-2 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2011942114 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in China Readers wishing to receive the Safari Press catalog, featuring many fine books on big-game hunting, wingshooting, and sporting firearms, should write to Safari Press, P.O. Box 3095, Long Beach, CA 90803, USA. Tel: (714) 894- 9080 or visit our Web site at www.safaripress.com Table of Contents Foreword by Tommy Caruthers ........................................................................................................................................vii Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................................ix Part I Egypt and Sudan Chapter 1 The Warrior Priests ................................................................................................................................1 -

Evolution and Changes in the Morphologies of Sudanese Cities Mohamed Babiker Ibrahima* and Omer Abdalla Omerb

Urban Geography, 2014 Vol. 35, No. 5, 735–756, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2014.919798 Evolution and changes in the morphologies of Sudanese cities Mohamed Babiker Ibrahima* and Omer Abdalla Omerb aDepartment of Geography, Hunter College of the City University of New York, New York, NY 10065, USA; bDepartment of Marketing, Entrepreneurship, Hospitality, and Tourism, The University of North Carolina-Greensboro, Greensboro, NC 27412, USA (Received 20 March 2013; accepted 17 March 2014) This article investigates the morphological evolution of Sudanese cities. The study of morphology or urban morphology involves consideration of town planning, building form, and the pattern of land and building utilization. Sudan has a long history of urbanization that contributed to the establishment of an early Sudanese civilization and European-style urban centers that have shaped the morphology of today’s cities. We identify three broad morphologies: indigenous, African-Islamic, and European style (colonial). The ongoing, rapid urbanization of African cities in general and Sudanese cities in particular points to a need to understand the structure of this urbanization. The morphology of cities includes not only physical structure, but the cultural heritage, economic, and historical values on which it is based. Therefore, preservation, redeve- lopment, and urban policy underlying future urban expansion must be based on the nature of cities’ morphologies and development. Keywords: urban morphology; indigenous cities; African-Islamic cities; European- style cities; Sudan Introduction The objective of this study is to investigate the evolving urban morphology of several Sudanese cities. Sudan has a long history of urbanization, beginning at the time of the Meroitic kingdom that flourished in the central part of the country from approximately 300 BCE to 350 CE (Adams, 1977; Shinnie, 1967). -

Welcome to Year 3 Home Learning Friday 3Rd July 2020 Daily Timetable

Welcome to Year 3 Home Learning Friday 3rd July 2020 Daily Timetable Before 9am Wake up 9am PE with The Body Coach Please complete the activities in your home learning books. 9.30am Maths Quiz TTRS Battle Email [email protected] if 10.30am Saturn V Titan you have any questions about Jupiter V Neptune the home learning and we will try to get back to you as soon 11am Break as possible. 11.15am Continue Writing Challenge Please email some home SPAG Activity learning you are proud of each week. We love seeing what you 12pm Lunch and time to play are getting up to. 1pm Reading for Pleasure 1.30pm Inquiry Challenge PE Challenge Here is your weekly PE challenge or activity to do which focuses on PE skills such as, agility, balance and co-ordination. Have a go during your morning break! Click here for the PE Challenge Maths Quiz 1. What time is being shown on 2. the clock? 3. 4. 5. The film Artic Adventures starts at 10:20am and finishes at 12:50pm. How long dies the film last? ____ hours ____ minutes 6. 8. 7. Nijah has football practice at 16:10. It last 45 minutes. What time does it finish? Maths Quiz Answers 3. 1. a) 5:20 or 20 minutes past 5 b) 5:40 or 20 minutes to 6 2. 4. a) 25 minutes 5. 2 hours 30 minutes 6. Both could be correct because we don’t know if the race started at 3.30am or 3.30pm. -

The Archaeology and Heritage of the Sudanese Red Sea Region: Importance, Findings, and Challenges

The Archaeology and Heritage of the Sudanese Red Sea Region: Importance, Findings, and Challenges AHMED ADAM Head Department of Archaeology - University of Khartoum Director of the Red Sea Project for Archaeological Research Abstract This paper seeks to shed a high light on the archaeological sites discovered in the area of Suakin, Arkaweet, and Sinkat as a part of the project of the department of Archaeology ß university of Khartoum, so, the archaeological sites discovered in this region belong to different periods such as Pre-Historic, Medieval, Islamic, and others are unknown, which means that the region used to link the Red Sea Cultures with those on the central Sudan and Egypt far north and Eretria in the east. Through this study I am also seeking to evaluate the field work (Archaeological and Ethnographic) conducted in the area of Arkaweet and Sinkat town, and Suakin port, then to put a plan for the managing and protecting the archaeologi- cal sites and ethnographic materials. Therefore I will follow or apply a number of approaches in this study such as description, survey analysis of the sites and its contents as well a comparison will be made between the results of the present study with the results of the previous studies in the field of archeology and ethnography conducted on other sites in the Sudanese Red Sea Region. The historical sources will also be compared with the study findings. Keywords Red Sea, Archaeology, Heritage, Sudan, Survey, Suakin 188 1. INTRODUCTION The Red Sea lies in an ideal geographical location between eastern and west- ern seas in general, and between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean in particular. -

Biology and Management of Fish Stocks in Bahir Dar Gulf, Lake Tana, Ethiopia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wageningen University & Research Publications Biology and management of fish stocks in Bahir Dar Gulf, Lake Tana, Ethiopia Tesfaye Wudneh Promotor: dr. E.A. Huisman, Hoogleraar in de Visteelt en Visserij Co-promotor: dr. ir. M.A.M. Machiels Universitair docent bij leerstoelgroep Visteelt en Visserij Biology and management of fish stocks in Bahir Dar Gulf, Lake Tana, Ethiopia Tesfaye Wudneh Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van de Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen, dr. C.M. Karssen, in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 22 juni 1998 des namiddags te half twee in de Aula van de Landbouwuniversiteit te Wageningen. Cover : Traditional fishing with reed boat and a motorised fishing boat (back-cover) on Lake Tana. Photo: Courtesy Interchurch Foundation Ethiopia/Eritrea (ISEE), Urk, the Netherlands. Cover design: Wim Valen. Printing: Grafisch Service Centrum Van Gils b.v., Wageningen CIP-DATA KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG Wudneh, Tesfaye Biology and management of fish stocks in Bahir Dar Gulf, Lake Tana, Ethiopia / Tesfaye Wudneh. - [S.I. : s.n.]. - III. Thesis Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen. - With ref. - With summary in Dutch. ISBN 90-5485-886-9 Tesfaye Wudneh 1998. Biology and management of fish stocks in Bahir Dar Gulf, Lake Tana, Ethiopia. The biology of the fish stocks of the major species in the Bahir Dar Gulf of Lake Tana, the largest lake in Ethiopia, has been studied based on data collected during August 1990 to September 1993. The distribution, reproduction patterns, growth and mortality dynamics and gillnet selectivity of these stocks are described. -

Reed Boats and Experimental Archaeology on Lake Titicaca

Paul Harmon tests the capabilities of the local totora reed boats. In the past few decades, hollow-hulled wooden boats of European design have largely replaced totora reed boats among the Aymara and Uru-Chipaya peoples of the region. Reed Boats and Experimental Archaeology on lake titicaca by alexei vranich, s much as archaeologists grumble about the scientific merit of Thor Heyerdahl’s paul harmon, and Kon Tiki journey from Peru to Polynesia, one thing is certain: he started a trend. On chris knutson the positive side, archaeologists began experimenting with a variety of ancient n o m technologies as a means to understand r a H l the past. On the negative side, a generation of adventurers u a P d A n decided that the best way to prove their ideas was to build a a h c i raft and set it adrift. Since the famous Kon Tiki, at least 40 sim- n a r V i ilar expeditions have generated adventure by inventing more e x e l and more improbable ways to get from one place to another. A 20 volume 47, number 2 expedition Boats made of everything from popsicle sticks to wine corks have been spotted all over the world, including a reed boat seen recently cruising down the Amazon River en route to Africa using powerful outboard motors! As we spent three months assembling nearly two million totora reeds into a giant bundle 13,000 feet above sea level on the edge of Lake Titicaca in South America, we wondered in which group we belonged, the archaeologists or the adventurers? TIWANAKU AND ITS MONOLITHS Around AD 500, one of the small villages along the shores of Lake Titicaca grew into the largest city that had ever existed in the Andes. -

Chapter 3: an Eco-Systemic Construct of Northern Riverain Sudan

University of Pretoria etd – Osman, A O S (2004) CHAPTER 3: AN ECO-SYSTEMIC CONSTRUCT OF NORTHERN RIVERAIN SUDAN 3.1 SUB PROBLEM 2 The study context needs to be identified eco-systemically. This needs to be initiated by the articulation of social, political, cultural and religious descriptions and the identification of the recurring themes in the literature of the region. 3.2 HYPOTHESIS 2 It is believed that through the eco-systemically based identification of recurring themes in the literature of/on the region, essential and incidental attributes of the place and culture can be articulated. This can become a tool in interpretation of tangible/ intangible artefacts, spatial interventions, and social practice. 3.3 OUTLINE OF CHAPTER 3 This chapter is initiated by looking at the history of the region. The reasons behind the delimitation of the area of study are articulated and justified. The recurring themes are then expressed through an intensive literature review. The origins of the people are explained and elaborated. The identity of the northern riverain people is established as a political and a religious concept. The northern Sudanese riverain people are thus introduced. 3.4 THE CONTEXT: ITS HISTORY AND ITS VALIDITY AS AN AREA OF STUDY Three main civilizations lived on this land, extending along the Sudanese Nile valley from the present northern border with Egypt to the town of Sennar on the Blue Nile and Kosti on the White Nile: the Kushites, the Meroites and the Funj (refer to Table 3.1). The Kushites had their centres at Kerma and then at Napata. -

Wwciguide April 2019.Pdf

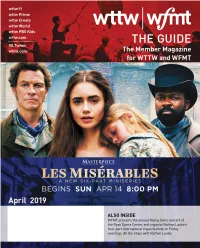

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT Dear Member, Renée Crown Public Media Center This month, we are excited to bring you a sweeping new adaptation of Victor Hugo’s 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 classic novel Les Misérables. This new six-part series, featuring an all-star cast including Dominic West, David Oyelowo, and recent Oscar winner Olivia Colman, tells the story of fugitive Jean Valjean, his relentless pursuer Inspector Javert, and other colorful characters Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 in turbulent 19th century France. We hope you’ll join us on Sunday nights for this epic Member and Viewer Services drama, and explore extra content on our website including episode recaps and fact vs. (773) 509-1111 x 6 fiction. If spring is a time of renewal, that is also certainly true of some of WTTW’s offerings Websites wttw.com in April, including eagerly awaited new seasons of three very different British detective wfmt.com series – Father Brown, Death in Paradise, and Unforgotten – and Mexico: One Plate at a Time, Jamestown, and Islands Without Cars. On wttw.com, as American Masters features Publisher newspaper magnate Joseph Pulitzer, we profile Chicago winners of the journalism and Anne Gleason arts award that bears his name, and highlight some extraordinary African American Art Director Tom Peth entrepreneurs in Chicago. WTTW Contributors WFMT will present the annual Rising Stars concert of the Ryan Opera Center, and Julia Maish Dan Soles organist Nathan Laube’s four-part international organ festival on Friday evenings, All the WFMT Contributors Stops with Nathan Laube. -

Battlefields

Nicole C. Vosseler – Beyond the Nile Battlefields Flight of the Khalifa after the Battle of Omdurman, 1898 Robert George Talbot Kelly, ca. 1900 Just like the Crimean War, one of the historical backgrounds in Beneath the Saffron Moon and briefly mentioned in Beyond the Nile, the Mahdist Revolt has hardly left any traces in the consciousness of the Western world - except in that of the British, since Great Britain was the only European power in- volved. If the name of the Mahdi is ever mentioned, it is mostly in relation to the sec- Mohammed Ahmad, the Mahdi ond campaign of 1896-1899 – and then only referring to one lieutenant who took part in this campaign und who later on became famous by his political activities, by premier minister and last but not least by his eccentric character: Winston S. Churchill. This second campaign though was an immediate consequence of the first campaign from 1881 to 1885, the historical backdrop of the novel. Not all regiments dispatched to Egypt and Sudan were involved in every battle, and therefore the depic- tion of the revolt in the novel is guided by the perspective of the Royal Sussex, the regiment of Jeremy, Stephen, Leonard, Royston, and Simon. © Nicole C. Vosseler 1 A regiment that, after the suppression of the ‘Urabi Revolt in Egypt and before its arrival at Khartoum, took part in three battles; one of them is only sketched briefly in the novel, while the other two are an extensive part of the storyline. Battle of El-Teb: February 29th, 1884 Strictly speaking, it should be called “the second Battle of El-Teb”, since this battle occurred as revenge, on the same site where on February 4th the year before, an array of 3,500 Egyptian soldiers under General Valentine Baker was almost completely erased by Osman Digna’s men. -

Sudan, Country Information

Sudan, Country Information SUDAN ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III HISTORY IV STATE STRUCTURES V HUMAN RIGHTS HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS ANNEX A - CHRONOLOGY ANNEX B - LIST OF MAIN POLITICAL PARTIES ANNEX C - GLOSSARY ANNEX D - THE POPULAR DEFENCE FORCES ACT 1989 ANNEX E - THE NATIONAL SERVICE ACT 1992 ANNEX F - LIST OF THE MAIN ETHNIC GROUPS OF SUDAN ANNEX G - REFERENCES TO SOURCE DOCUMENTS 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum/human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum/human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for accuracy, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up-to-date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. -

The History of the People's of the Eastern Desert

The History of the Peoples of the Eastern Desert edited by Hans Barnard and Kim Duistermaat Monograph 73 Cotsen Institute of Archaeology University of California, Los Angeles THE COTSEN INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY PRESS is the publishing unit of the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at UCLA. The Cotsen Institute is a premier research organization dedicated to the creation, dissemination, and conservation of archaeological knowledge and heritage. It is home to both the Interdepartmental Archaeology Graduate Program and the UCLA/Getty Master’s Program in the Conservation of Archaeological and Ethnographic Materials. The Cotsen Institute provides a forum for innovative faculty research, graduate education, and public programs at UCLA in an effort to impact positively the academic, local and global communities. Established in 1973, the Cotsen Institute is at the forefront of archaeological research, education, conservation and publication and is an active contributor to interdisciplinary research at UCLA. The Cotsen Institute Press specializes in producing high-quality academic volumes in several different series, including Monographs, World Heritage and Monuments, Cotsen Advanced Seminars, and Ideas, Debates and Perspectives. The Press is committed to making the fruits of archaeological research accessible to professionals, scholars, students, and the general public. We are able to do this through the generosity of Lloyd E. Cotsen, longtime Institute volunteer and benefactor, who has provided an endowment that allows us to subsidize our publishing -

Middle Eastern Base Race in North-Eastern Africa

STUDIES IN AFRICAN SECURITY Turkey, United Arab Emirates and other Middle Eastern States Middle Eastern Base Race in North-Eastern Africa This text is a part of the FOI report Foreign military bases and installations in Africa. Twelve state actors are included in the report: China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Russia, Spain, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, and United States. Middle Eastern states are increasing their military region. Turkey’s political interests are in line with those presence in Africa. Turkey and the United Arab of Qatar on the question of political Islam and the MB, Emirates (UAE), two influential Sunni powers with but clash with the agenda of the UAE and Saudi Arabia. contrary views on regional order and political Islam, The conflict among the Sunni powers has intensified since are expanding their foothold in north-eastern Africa. the Arab Spring in 2010, in particular since the UAE-led Turkey has opened a military training facility in blockade against Qatar in 2017. Eastern Africa has thus Somalia and may build a naval dock for military use become an arena for the rivalry between regional powers in Sudan. The UAE has established bases in Eritrea of the Middle East. and Libya, and is currently constructing a base in President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his AK party have Somaliland. However, Turkey and UAE are not the strengthened the Sunni Muslim identity of the Turkish only Middle Eastern countries with a military presence state, while de facto approving a neo-Ottoman foreign in Africa. Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Israel, and Iran, also policy that implies a growing focus on the Middle East seem to have military activities on the Horn of Africa.