Reflections on the Red Sea Style: Beyond the Surface of Coastal Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution and Changes in the Morphologies of Sudanese Cities Mohamed Babiker Ibrahima* and Omer Abdalla Omerb

Urban Geography, 2014 Vol. 35, No. 5, 735–756, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2014.919798 Evolution and changes in the morphologies of Sudanese cities Mohamed Babiker Ibrahima* and Omer Abdalla Omerb aDepartment of Geography, Hunter College of the City University of New York, New York, NY 10065, USA; bDepartment of Marketing, Entrepreneurship, Hospitality, and Tourism, The University of North Carolina-Greensboro, Greensboro, NC 27412, USA (Received 20 March 2013; accepted 17 March 2014) This article investigates the morphological evolution of Sudanese cities. The study of morphology or urban morphology involves consideration of town planning, building form, and the pattern of land and building utilization. Sudan has a long history of urbanization that contributed to the establishment of an early Sudanese civilization and European-style urban centers that have shaped the morphology of today’s cities. We identify three broad morphologies: indigenous, African-Islamic, and European style (colonial). The ongoing, rapid urbanization of African cities in general and Sudanese cities in particular points to a need to understand the structure of this urbanization. The morphology of cities includes not only physical structure, but the cultural heritage, economic, and historical values on which it is based. Therefore, preservation, redeve- lopment, and urban policy underlying future urban expansion must be based on the nature of cities’ morphologies and development. Keywords: urban morphology; indigenous cities; African-Islamic cities; European- style cities; Sudan Introduction The objective of this study is to investigate the evolving urban morphology of several Sudanese cities. Sudan has a long history of urbanization, beginning at the time of the Meroitic kingdom that flourished in the central part of the country from approximately 300 BCE to 350 CE (Adams, 1977; Shinnie, 1967). -

The Archaeology and Heritage of the Sudanese Red Sea Region: Importance, Findings, and Challenges

The Archaeology and Heritage of the Sudanese Red Sea Region: Importance, Findings, and Challenges AHMED ADAM Head Department of Archaeology - University of Khartoum Director of the Red Sea Project for Archaeological Research Abstract This paper seeks to shed a high light on the archaeological sites discovered in the area of Suakin, Arkaweet, and Sinkat as a part of the project of the department of Archaeology ß university of Khartoum, so, the archaeological sites discovered in this region belong to different periods such as Pre-Historic, Medieval, Islamic, and others are unknown, which means that the region used to link the Red Sea Cultures with those on the central Sudan and Egypt far north and Eretria in the east. Through this study I am also seeking to evaluate the field work (Archaeological and Ethnographic) conducted in the area of Arkaweet and Sinkat town, and Suakin port, then to put a plan for the managing and protecting the archaeologi- cal sites and ethnographic materials. Therefore I will follow or apply a number of approaches in this study such as description, survey analysis of the sites and its contents as well a comparison will be made between the results of the present study with the results of the previous studies in the field of archeology and ethnography conducted on other sites in the Sudanese Red Sea Region. The historical sources will also be compared with the study findings. Keywords Red Sea, Archaeology, Heritage, Sudan, Survey, Suakin 188 1. INTRODUCTION The Red Sea lies in an ideal geographical location between eastern and west- ern seas in general, and between the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean in particular. -

Chapter 3: an Eco-Systemic Construct of Northern Riverain Sudan

University of Pretoria etd – Osman, A O S (2004) CHAPTER 3: AN ECO-SYSTEMIC CONSTRUCT OF NORTHERN RIVERAIN SUDAN 3.1 SUB PROBLEM 2 The study context needs to be identified eco-systemically. This needs to be initiated by the articulation of social, political, cultural and religious descriptions and the identification of the recurring themes in the literature of the region. 3.2 HYPOTHESIS 2 It is believed that through the eco-systemically based identification of recurring themes in the literature of/on the region, essential and incidental attributes of the place and culture can be articulated. This can become a tool in interpretation of tangible/ intangible artefacts, spatial interventions, and social practice. 3.3 OUTLINE OF CHAPTER 3 This chapter is initiated by looking at the history of the region. The reasons behind the delimitation of the area of study are articulated and justified. The recurring themes are then expressed through an intensive literature review. The origins of the people are explained and elaborated. The identity of the northern riverain people is established as a political and a religious concept. The northern Sudanese riverain people are thus introduced. 3.4 THE CONTEXT: ITS HISTORY AND ITS VALIDITY AS AN AREA OF STUDY Three main civilizations lived on this land, extending along the Sudanese Nile valley from the present northern border with Egypt to the town of Sennar on the Blue Nile and Kosti on the White Nile: the Kushites, the Meroites and the Funj (refer to Table 3.1). The Kushites had their centres at Kerma and then at Napata. -

Journal of Urban History

Journal of Urban History http://juh.sagepub.com/ Urban Forms and Civic Space in Nineteenth- to Early Twentieth-Century Bangkok and Rangoon Elizabeth Howard Moore and Navanath Osiri Journal of Urban History 2014 40: 158 originally published online 27 September 2013 DOI: 10.1177/0096144213504381 The online version of this article can be found at: http://juh.sagepub.com/content/40/1/158 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: Urban History Association Additional services and information for Journal of Urban History can be found at: Email Alerts: http://juh.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://juh.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - Nov 26, 2013 OnlineFirst Version of Record - Sep 27, 2013 What is This? Downloaded from juh.sagepub.com at SOAS London on December 1, 2013 JUH40110.1177/0096144213504381Journal of Urban HistoryHoward-Moore and Osiri 504381research-article2013 Article Journal of Urban History 2014, Vol 40(1) 158 –177 Urban Forms and Civic Space in © 2013 SAGE Publications Reprints and permissions: Nineteenth- to Early Twentieth- sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0096144213504381 Century Bangkok and Rangoon juh.sagepub.com Elizabeth Howard Moore1 and Navanath Osiri2 Abstract Buddhist spaces in Bangkok and Rangoon both had long common traditions prior to nineteenth- and early twentieth-century colonial incursions. Top–down central city planning with European designs transformed both cities. While Siamese kings personally initiated civic change that began to widen economic and social interaction of different classes, British models segregated European, Burmese, Indian, and Chinese populations to exacerbate social differences. -

Materiality and Construction of a Church in Myanmar

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Theses from the M. Arch. Program Architecture, College of Spring 5-3-2021 Materiality and Construction of a Church in Myanmar Sunkist Judson University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/marchthesis Part of the Architecture Commons Judson, Sunkist, "Materiality and Construction of a Church in Myanmar" (2021). Theses from the M. Arch. Program. 31. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/marchthesis/31 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses from the M. Arch. Program by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. University of Nebraska-Lincoln Materiality and Construction of a Church in Myanmar By: Sunkist Judson A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FUL- FILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Master of Architecture APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE: Sign and Date Dr. Sharon Kuska Materiality and Construction of a Church in Myanmar Sunkist Judson April 29th, 2021 ARCH 544 Thesis Spring 2021 01 02 Abstract This is my investigation related to Theinla village church. This is an investigation of architectural impacts on a protestant religious house of worship experience through a cultural case study. Churches were built and design based on worship culture and traditions. Churches have evolved for over two thousand years due to innovation and technology and imitating previous architecture styles. The way people worship in protestant religion is a little different in every culture. I would like to find out if there is any overlap in Baptist churches in different cultures. -

University of Mandalay Mandalay, Myanmar March 2007 Tint Lwin

University of Mandalay ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN PAKHAN GYI DURING THE MONARCHICAL DAYS Tint Lwin Mandalay, Myanmar March 2007 ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN PAKHAN GYI DURING THE MONARCHICAL DAYS University of Mandalay ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN PAKHAN GYI DURING THE MONARCHICAL DAYS A Dissertation submitted to University of Mandalay in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History Department of History Tint Lwin 4 Ph.D/Hist.-3 Mandalay, Myanmar March 2007 University of Mandalay ART AND ARCHITECTURE IN PAKHAN GYI DURING THE MONARCHICAL DAYS By Tint Lwin, B.A(Hist:), M.A. 4 Ph.D./Hist.-3 (2006-07) This Dissertation is submitted to the Board of Examiners In History, University of Mandalay in Candidature For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved External Examiner, Referee Supervisor Member Member Co-Supervisor Chairperson Abstract In writing this dissertation on the "Art and Architecture in Pakhangyi during the monarchical days", every conceivable aspect has been covered, and the dissertation is divided into four chapters. In writing the First Chapter, the artifacts and implements of Neolithic age period, the religious edifices and wall paintings are mainly used as evidences to show the development of Pakhangyi region as one of the main centres of Myanmar civilization other than Bagan and other places of cultural interest. The First Chapter asserts the historical and cultural legitimacy of the Pakhangyi region by presenting its visible facets of successive periods starting from the stone age: stone implements, how the very term Pakhangyi emerge, the oldest villages, the massive city wall, how the city was rebuilt five times, the quality of bricks used and the pattern of brick bonding, water supply system, agriculture and the region’s inhabitants. -

The History of the People's of the Eastern Desert

The History of the Peoples of the Eastern Desert edited by Hans Barnard and Kim Duistermaat Monograph 73 Cotsen Institute of Archaeology University of California, Los Angeles THE COTSEN INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY PRESS is the publishing unit of the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at UCLA. The Cotsen Institute is a premier research organization dedicated to the creation, dissemination, and conservation of archaeological knowledge and heritage. It is home to both the Interdepartmental Archaeology Graduate Program and the UCLA/Getty Master’s Program in the Conservation of Archaeological and Ethnographic Materials. The Cotsen Institute provides a forum for innovative faculty research, graduate education, and public programs at UCLA in an effort to impact positively the academic, local and global communities. Established in 1973, the Cotsen Institute is at the forefront of archaeological research, education, conservation and publication and is an active contributor to interdisciplinary research at UCLA. The Cotsen Institute Press specializes in producing high-quality academic volumes in several different series, including Monographs, World Heritage and Monuments, Cotsen Advanced Seminars, and Ideas, Debates and Perspectives. The Press is committed to making the fruits of archaeological research accessible to professionals, scholars, students, and the general public. We are able to do this through the generosity of Lloyd E. Cotsen, longtime Institute volunteer and benefactor, who has provided an endowment that allows us to subsidize our publishing -

Middle Eastern Base Race in North-Eastern Africa

STUDIES IN AFRICAN SECURITY Turkey, United Arab Emirates and other Middle Eastern States Middle Eastern Base Race in North-Eastern Africa This text is a part of the FOI report Foreign military bases and installations in Africa. Twelve state actors are included in the report: China, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Russia, Spain, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, and United States. Middle Eastern states are increasing their military region. Turkey’s political interests are in line with those presence in Africa. Turkey and the United Arab of Qatar on the question of political Islam and the MB, Emirates (UAE), two influential Sunni powers with but clash with the agenda of the UAE and Saudi Arabia. contrary views on regional order and political Islam, The conflict among the Sunni powers has intensified since are expanding their foothold in north-eastern Africa. the Arab Spring in 2010, in particular since the UAE-led Turkey has opened a military training facility in blockade against Qatar in 2017. Eastern Africa has thus Somalia and may build a naval dock for military use become an arena for the rivalry between regional powers in Sudan. The UAE has established bases in Eritrea of the Middle East. and Libya, and is currently constructing a base in President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his AK party have Somaliland. However, Turkey and UAE are not the strengthened the Sunni Muslim identity of the Turkish only Middle Eastern countries with a military presence state, while de facto approving a neo-Ottoman foreign in Africa. Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Israel, and Iran, also policy that implies a growing focus on the Middle East seem to have military activities on the Horn of Africa. -

Myanmar (Burma): a Reading Guide Andrew Selth

Griffith Asia Institute Research Paper Myanmar (Burma): A reading guide Andrew Selth i About the Griffith Asia Institute The Griffith Asia Institute (GAI) is an internationally recognised research centre in the Griffith Business School. We reflect Griffith University’s longstanding commitment and future aspirations for the study of and engagement with nations of Asia and the Pacific. At GAI, our vision is to be the informed voice leading Australia’s strategic engagement in the Asia Pacific— cultivating the knowledge, capabilities and connections that will inform and enrich Australia’s Asia-Pacific future. We do this by: i) conducting and supporting excellent and relevant research on the politics, security, economies and development of the Asia-Pacific region; ii) facilitating high level dialogues and partnerships for policy impact in the region; iii) leading and informing public debate on Australia’s place in the Asia Pacific; and iv) shaping the next generation of Asia-Pacific leaders through positive learning experiences in the region. The Griffith Asia Institute’s ‘Research Papers’ publish the institute’s policy-relevant research on Australia and its regional environment. The texts of published papers and the titles of upcoming publications can be found on the Institute’s website: www.griffith.edu.au/asia-institute ‘Myanmar (Burma): A reading guide’ February 2021 ii About the Author Andrew Selth Andrew Selth is an Adjunct Professor at the Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University. He has been studying international security issues and Asian affairs for 45 years, as a diplomat, strategic intelligence analyst and research scholar. Between 1974 and 1986 he was assigned to the Australian missions in Rangoon, Seoul and Wellington, and later held senior positions in both the Defence Intelligence Organisation and Office of National Assessments. -

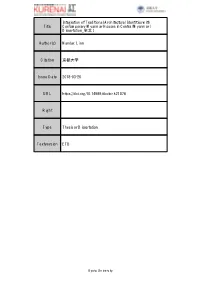

Title Integration of Traditional Architectural Identities With

Integration of Traditional Architectural Identities with Title Contemporary Myanmar Houses in Central Myanmar( Dissertation_全文 ) Author(s) Nandar, Linn Citation 京都大学 Issue Date 2018-03-26 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/doctor.k21078 Right Type Thesis or Dissertation Textversion ETD Kyoto University Integration of Traditional Architectural Identities with Contemporary Myanmar Houses in Central Myanmar Nandar Linn 2018 Integration of Traditional Architectural Identities with Contemporary Myanmar Houses in Central Myanmar A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Engineering Nandar Linn 2018 KYOTO UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL AND EARTH RESOURCES ENGINEERING i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express her sincere and deepest gratitude to Professor Masashi Kawasaki from Urban and Landscape Design Laboratory, Department of Civil and Earth Resources Engineering, Kyoto University for accepting her as his student and giving her precious guidance, criticism and generous support for the accomplishment of this thesis. She is deeply indebted to the continuous help, understanding and guidance from Associate Professor Keita Yamaguchi from Urban and Landscape Design Laboratory. Sincere thanks and appreciation are also extended to Professor Yoshiaki Kubota for his valuable suggestions and support before and even after he has been appointed in Toyama University. She owes a debt of gratitude to Professor Nobuhiro Uno from Department of Civil and Earth Resources Engineering who generously shared his knowledge and suggestions throughout the reviewing process of her dissertation. She is greatly indebted to all the professors in Department of Civil and Earth Resources Engineering and the lecturers who have contributed in Kyoto University Global COE Program on Human Security Engineering for all of their valuable lectures. -

Egyptian Rule in the Sudan

SOME SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC ASPECTS OF TURKO - EGYPTIAN RULE IN THE SUDAN GABRIEL R. WARBURG Between 1821 and 1885 most of the area constituting the present Su- dan came under Turko-Egyptian rule. The annexation of the Sudan to Egypt was undertaken in 1820-1 by Muhammad `Ali, the Ottoman Vali of Egypt, and was completed under his grandson, the Khedive Ismacil, who extended this rule to the Great Lakes in the south and to Bahr al- Ghazal and Darfur in the west. In the history of the Sudan, this period became known as the (first) Turkiyya. The term Turkiyya is not really ar- bitrary since Egypt was itself an Ottoman province, ruled by an Ottoman (Albanian) dynasty. Moreover, most of the high officials and army officers serving in the Sudan were of Ottoman rather than Egyptian origin. Last- ly, though Arabic made considerable headway during the second half of the century in daily administrative usage, the senior officers and off~ cials continued to communicate in Turkish, since their superior- the Khedive - was a Turk and Turkish was the language of the ruling elite. Hence, when the Mahdist revolt errupted in June 1881, its main enemy were the Turks who had oppressed the Sudanese and had - according to the Mahdi - corrupted Islam. a. European Historical and other Writings on N~ neteenth-Century Sudan Until the second half of the twentieth century western views both on Turkish rule in the Sudan as well as on the Mahdiyya, were largely based on the writings of European trades, explorers and soldiers of for- tune. -

The Significance of the Visual Culture of Three Foreign Temples at Bodhgaya (India) a Sri Lankan, Burmese and Thai Temple

15-07-2016 The significance of the visual culture of three foreign temples at Bodhgaya (India) A Sri Lankan, Burmese and Thai Temple Student: Shita Bakker, Student No: S0951730 Master Asian Studies, History, Arts and Culture of Asia Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Marijke J. Klokke Word count: 15.298 Content Chapter 1. Introduction 1.1 Brief background information and description of three foreign temples 1.2 Theravada Buddhism 1.3 Previous literature on the subject 1.4 Relevance of paper and research questions 1.5 Methodology and approach 1.6 Short note on terminology Chapter 2. Bodhgaya, from a lieu de mémoire into a global village 2.1 History and memory 2.2 The idea of conscious remembering 2.3 Conclusion Chapter 3. The visual elements of the foreign temples expressing Bodhgaya as a lieu de mémoire 3.1 The Sri Lankan Temple and Bodhgaya as a lieu de mémoire 3.2 Sri Lanka and its relation to Bodhgaya 3.3 The Burmese Temple and Bodhgaya as a lieu de mémoire 3.4 Burma and its relation to Bodhgaya 3.5 The Thai Temple and Bodhgaya as a lieu de mémoire 3.6 Thailand and its relation to Bodhgaya 3.7 Conclusion Chapter 4. The temples and the visual expression of their domestic cultures 4.1 The Sri Lankan Temple and its visual culture ` 4.2 The Burmese Temple and its visual culture 4.3 The Thai Temple and its visual culture 4.4 Conclusion Chapter 5. Conclusion 2 Chapter 1. Introduction Bodhgaya is situated in the state of Bihar in India and is known as the place where the Buddha became awakened while sitting under a Bodhi tree, which is marked by the diamond seat (Sanskrit: vajrasana).