Reed Boats and Experimental Archaeology on Lake Titicaca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Welcome to Year 3 Home Learning Friday 3Rd July 2020 Daily Timetable

Welcome to Year 3 Home Learning Friday 3rd July 2020 Daily Timetable Before 9am Wake up 9am PE with The Body Coach Please complete the activities in your home learning books. 9.30am Maths Quiz TTRS Battle Email [email protected] if 10.30am Saturn V Titan you have any questions about Jupiter V Neptune the home learning and we will try to get back to you as soon 11am Break as possible. 11.15am Continue Writing Challenge Please email some home SPAG Activity learning you are proud of each week. We love seeing what you 12pm Lunch and time to play are getting up to. 1pm Reading for Pleasure 1.30pm Inquiry Challenge PE Challenge Here is your weekly PE challenge or activity to do which focuses on PE skills such as, agility, balance and co-ordination. Have a go during your morning break! Click here for the PE Challenge Maths Quiz 1. What time is being shown on 2. the clock? 3. 4. 5. The film Artic Adventures starts at 10:20am and finishes at 12:50pm. How long dies the film last? ____ hours ____ minutes 6. 8. 7. Nijah has football practice at 16:10. It last 45 minutes. What time does it finish? Maths Quiz Answers 3. 1. a) 5:20 or 20 minutes past 5 b) 5:40 or 20 minutes to 6 2. 4. a) 25 minutes 5. 2 hours 30 minutes 6. Both could be correct because we don’t know if the race started at 3.30am or 3.30pm. -

Biology and Management of Fish Stocks in Bahir Dar Gulf, Lake Tana, Ethiopia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wageningen University & Research Publications Biology and management of fish stocks in Bahir Dar Gulf, Lake Tana, Ethiopia Tesfaye Wudneh Promotor: dr. E.A. Huisman, Hoogleraar in de Visteelt en Visserij Co-promotor: dr. ir. M.A.M. Machiels Universitair docent bij leerstoelgroep Visteelt en Visserij Biology and management of fish stocks in Bahir Dar Gulf, Lake Tana, Ethiopia Tesfaye Wudneh Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van de Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen, dr. C.M. Karssen, in het openbaar te verdedigen op maandag 22 juni 1998 des namiddags te half twee in de Aula van de Landbouwuniversiteit te Wageningen. Cover : Traditional fishing with reed boat and a motorised fishing boat (back-cover) on Lake Tana. Photo: Courtesy Interchurch Foundation Ethiopia/Eritrea (ISEE), Urk, the Netherlands. Cover design: Wim Valen. Printing: Grafisch Service Centrum Van Gils b.v., Wageningen CIP-DATA KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG Wudneh, Tesfaye Biology and management of fish stocks in Bahir Dar Gulf, Lake Tana, Ethiopia / Tesfaye Wudneh. - [S.I. : s.n.]. - III. Thesis Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen. - With ref. - With summary in Dutch. ISBN 90-5485-886-9 Tesfaye Wudneh 1998. Biology and management of fish stocks in Bahir Dar Gulf, Lake Tana, Ethiopia. The biology of the fish stocks of the major species in the Bahir Dar Gulf of Lake Tana, the largest lake in Ethiopia, has been studied based on data collected during August 1990 to September 1993. The distribution, reproduction patterns, growth and mortality dynamics and gillnet selectivity of these stocks are described. -

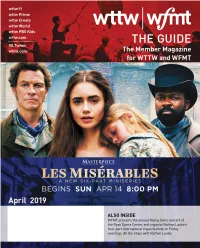

Wwciguide April 2019.Pdf

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT Dear Member, Renée Crown Public Media Center This month, we are excited to bring you a sweeping new adaptation of Victor Hugo’s 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 classic novel Les Misérables. This new six-part series, featuring an all-star cast including Dominic West, David Oyelowo, and recent Oscar winner Olivia Colman, tells the story of fugitive Jean Valjean, his relentless pursuer Inspector Javert, and other colorful characters Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 in turbulent 19th century France. We hope you’ll join us on Sunday nights for this epic Member and Viewer Services drama, and explore extra content on our website including episode recaps and fact vs. (773) 509-1111 x 6 fiction. If spring is a time of renewal, that is also certainly true of some of WTTW’s offerings Websites wttw.com in April, including eagerly awaited new seasons of three very different British detective wfmt.com series – Father Brown, Death in Paradise, and Unforgotten – and Mexico: One Plate at a Time, Jamestown, and Islands Without Cars. On wttw.com, as American Masters features Publisher newspaper magnate Joseph Pulitzer, we profile Chicago winners of the journalism and Anne Gleason arts award that bears his name, and highlight some extraordinary African American Art Director Tom Peth entrepreneurs in Chicago. WTTW Contributors WFMT will present the annual Rising Stars concert of the Ryan Opera Center, and Julia Maish Dan Soles organist Nathan Laube’s four-part international organ festival on Friday evenings, All the WFMT Contributors Stops with Nathan Laube. -

Karyotype Characterization of Four Mexican Species of Schoenoplectus (Cyperaceae) and First Report of Polyploid Mixoploidy for the Family

Caryologia International Journal of Cytology, Cytosystematics and Cytogenetics ISSN: 0008-7114 (Print) 2165-5391 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tcar20 Karyotype characterization of four Mexican species of Schoenoplectus (Cyperaceae) and first report of polyploid mixoploidy for the family Jorge A. Tena-Flores, M. Socorro González-Elizondo, Yolanda Herrera-Arrieta, Norma Almaraz-Abarca, Netzahualcóyotl Mayek-Pérez & André L.L. Vanzela To cite this article: Jorge A. Tena-Flores, M. Socorro González-Elizondo, Yolanda Herrera- Arrieta, Norma Almaraz-Abarca, Netzahualcóyotl Mayek-Pérez & André L.L. Vanzela (2014) Karyotype characterization of four Mexican species of Schoenoplectus (Cyperaceae) and first report of polyploid mixoploidy for the family, Caryologia, 67:2, 124-134, DOI: 10.1080/00087114.2014.931633 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00087114.2014.931633 Published online: 20 Aug 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 51 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tcar20 Download by: [148.204.124.71] Date: 23 February 2017, At: 09:58 Caryologia: International Journal of Cytology, Cytosystematics and Cytogenetics, 2014 Vol. 67, No. 2, 124–134, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00087114.2014.931633 Karyotype characterization of four Mexican species of Schoenoplectus (Cyperaceae) and first report of polyploid mixoploidy for the family Jorge A. Tena-Floresa*, M. Socorro -

Early Settlement Ofrapa Nui (Easter Island)

Early Settlement ofRapa Nui (Easter Island) HELENE MARTINSSON-WALLIN AND SUSAN J. CROCKFORD RAPA NUl, THE SMALL REMOTE ISLAND that constitutes the easternmost corner of the Polynesian triangle, was found and populated long before the Europeans "discovered" this part ofthe world in 1722. The long-standing questions concern ing this remarkable island are: who were the first to populate the island, at what time was it populated, and did the Rapa Nui population and development on the island result from a single voyage? Over the years there has been much discussion, speculation, and new scientific results concerning these questions. This has resulted in several conferences and numerous scientific and popular papers and monographs. The aim ofthis paper is to present the contemporary views on these issues, drawn from the results of the last 45 years of archaeological research on the island (Fig. 1), and to describe recent fieldwork that Martinsson-Wallin completed on Rapa Nui. Results from the Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Rapa Nui in 1955 1956 suggest that the island was populated as early as c. A.D. 400 (Heyerdahl and Ferdon 1961: 395). This conclusion was drawn from a single radiocarbon date. This dated carbon sample (K-502) was found in association with the so-called Poike ditch on the east side of the island. The sample derived from a carbon con centration on the natural surface, which had been covered by soil when the ditch was dug. The investigator writes the following: There is no evidence to indicate that the fire from which the carbon was derived actually burned at the spot where the charcoal occurred, but it is clear that it was on the surface of the ground at the time the first loads of earth were carried out of the ditch and deposited over it. -

F-Transcript of Proceedings, Vol. III-June 18, 2014

GILA RIVER VOL. III 06/18/2014 537 1 BEFORE THE 2 ARIZONA NAVIGABLE STREAM ADJUDICATION COMMISSION 3 4 IN THE MATTER OF THE NAVIGABILITY ) OF THE GILA RIVER FROM THE NEW ) NO. 03-007-NAV 5 MEXICO BORDER TO THE CONFLUENCE ) WITH THE COLORADO RIVER, GREENLEE, ) ADMINISTRATIVE 6 GRAHAM, GILA, PINAL, MARICOPA AND ) HEARING YUMA COUNTIES, ARIZONA. ) 7 ___________________________________) 8 9 10 At: Phoenix, Arizona 11 Date: June 18, 2014 12 Filed: July 11, 2014 13 14 REPORTER'S TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS 15 VOLUME III 16 Pages 537 through 771, inclusively 17 18 19 COASH & COASH, INC. Court Reporting, Video & Videoconferencing 20 1802 N. 7th Street, Phoenix, AZ 85006 602-258-1440 [email protected] 21 Prepared by: 22 Gary W. HILL, RMR, CRR Certificate No. 50812 23 24 25 COASH & COASH, INC. (602) 258-1440 www.coashandcoash.com Phoenix, AZ GILA RIVER VOL. III 06/18/2014 538 1 INDEX TO EXAMINATIONS 2 WITNESS PAGE 3 DONALD D. FARMER 4 Direct Examination by Mr. Katz 542 Cross-Examination by Mr. Hood 578 5 Cross-Examination by Mr. Sparks 595 Cross-Examination by Mr. Murphy 616 6 Cross-Examination by Mr. McGinnis 623 Redirect Examination by Mr. Katz 634 7 8 JONATHAN EDWARD FULLER (Continuing) 9 Cross-Examination by Mr. Sparks 643 Cross-Examination by Ms. Kolsrud 697 10 Cross-Examination by Mr. Helm 701 Redirect Examination by Mr. Katz 706 11 Redirect Examination by Ms. Hernbrode 733 Further Redirect Examination by Mr. Katz 735 12 Examination by Commissioner Allen 743 13 ALLEN GOOKIN 14 Direct Examination by Mr. -

The Utilization of Emergent Aquatic Plants for Biomass Energy Systems Development

SERI/TR-98281-03 UC Category: 61a The Utilization of Emergent Aquatic Plants for Biomass Energy Systems Development S. Kresovich C. K. Wagner D. A. Scantland S. S. Groet W. T. Lawhon Battelle 505 King Avenue Columbus, Ohio 43201 February 1982 Prepared Under Task No. 3337.01 WPA No. 274-81 Solar Energy Research Institute A Division of Midwest Research Institute 1617 Cole Boulevard Golden, Colorado 80401 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy Contract No. EG-77-C-01-4042 Printed in the United States of America Ava ilabl e from: National Technical Information Service U.S. Department of Commerce 5285 Port Royal Road Springfield, VA 22161 Price: Microfiche $3.00 Printed Copy $6.50 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. Neith~r the United States nor the United States Depart ment of Energy, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, complete ness or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. FOREWORD Emergent aquatic plants, such as reeds, cattails, and bull rushes, are highly productive and are potentially significant resources for alcohol and solid fuel production. It has been estimated that if one-half of the 65,600 mi 2 of marshland in the United States were used for emergent biomass energy plantations, approximately 5% of present total national energy requirements might be met. -

(Turfs) and the Management of Small-Scale Fisheries

TERRITORIAL USE-RIGHTS IN FISHING (TURFS) AND THE MANAGEMENT OF SMALL-SCALE FISHERIES: THE CASE OF LAKE TITICACA (PERU). By DOMINIQUE P. LEVIEIL DEUG, Institut National Agronomique Paris-Grignon, 1974 Ing. Agro-Halieute, Institut National Agronomique, Paris-Grignon, 1977 M.A. (Marine Affair), University of Washington, 1979 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (School of Community and Regional Planning) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA June 1987 © Dominique P. Levieil, 1987 4 6 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date DE-6(3/81) ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to evaluate whether the Territorial Use- Rights in Fishing (TURFs) of Lake Titieaca, Peru, are effective in overcoming the common property problem of typical fisheries and therefore whether TURFs may prove valuable as part of a more formal management system. It has recently been argued that TURFs should be incorporated into small-scale fisheries management schemes since they should be effective in controlling fishing effort, in promoting a more equitable distribution of the benefits from fishing and in reducing administrative inefficiencies. -

Relación Fenética De Especies Del Orden Poales De Interés Económico En La Laguna El Paraíso, Huacho, 2017

Relación fenética de especies del orden Poales de interés económico en la laguna El Paraíso, Huacho, 2017 Phenetic relationship of Poales species of economic interest in the El Paraíso lagoon, Huacho, 2017 Hermila B. Díaz Pillasca1, Zoila Honorio Durand2, Carmen Rojas Zenozain1, Miguel A. Durand Meza1 RESUMEN Objetivo: Estimar la relación fenética de las especies del orden Poales de interés económico de la laguna El Paraíso, Huacho – 2017. Métodos: Para lo cual se aplicó el diseño de una sola casilla; donde la población estuvo constituida por todos los individuos de las especies seleccionadas; de la cual se extrajo una muestra de 43 individuos, mediante un diseño aleatorio estratificado; eligiéndose 34 caracteres cualitativos y 13 cuantitativos; utilizados para estimar variabilidad y distancia fenética dentro y entre especies, mediante estadística descriptiva, inferencial (ANVA y Tukey) y Taxonomía Numérica, a través del programa Past 3.0. Resultados: Los caracteres cuantitativos de interés económico (longitud de culmo) muestran una baja variabilidad fenotípica (CV < 12%) intra e interespecífica, presumiblemente por influencia ambiental; la distancia fenética intraespecífica es estrecha en las tres especies evaluadas, siendo T. dominguensis, la que muestra mayor número de formas fenotípicas; y, C. laevigatus tiene una mayor distancia fenética con respecto a S. californicus y T. dominguensis; las mismas que son iguales entre sí. Conclusiones: El humedad es una comunidad compleja pero poco estable. Palabras clave: Relación fenética, Poales, -

Use Style: Paper Title

Volume 6, Issue 2, February – 2021 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456-2165 Territorial Occupation in the Coastal Strip and the Environmental Sustainability of the Wetland Ecosystem of Huanchaco-Peru Carlos A. Bocanegra García Nelson GustavoYwanaga Reh National university of Trujillo National university of Trujillo Trujillo, Perú Trujillo, Perú Zoila Culquichicón Malpica National university of Trujillo Trujillo, Perú Abstract:- Results of the “occupation of the coastal territory on the environmental sutainability of the It is alarming what is recorded in Spain, where a wetlands of Huanchaco-Perú” are presented. The work ranking of coastal destruction was established and was carried out on base of the management and showed that the Mediterranean is the región most processing satellite images, georeferenced databases that affected. The three comunities that lead the destruction serve to obtain past and present information, the method of coastal ecosystems due to urbanizations are used relates different sources of information from the Catalunya, which has the highest percentage of databases of the District Municipality of Huanchaco with urbanized coastal área: 26.4%, the Valenciana remote sensing images from Google Earth. The results community occupies second place, with 23.1% of its show accelerated growth of the mainly urban population, coastline degraded, and in third place is Andalucía with settled on the coast in detriment of adjacent áreas 15.4%. Furthermore, looking only at the beaches, the characterized by precaurious basic. worst provinces are Barcelona and Malaga with 83.6% and Alicante with 80.3%, of their beach line surrounded Keywords:- Territorial Occupation, Coastal Strip, Wetlands by cement (PALOMA NUCHE, 2018). -

Uros Hand Made Reed Floating Islands

Uros hand made reed floating islands A proved ancient technique Today a closed cycle in practice to learn from Tomorrow an innovative development Rocío Torres Méndez Because of global warming, rising sea levels and the running out of fossil fuels, it is important to look for sustainable adaptable solutions. Therefore special attention should be given to the potential of floating reeds in construction. This paper is about a closed cycle example in practice, to learn from. It tells the history of a millenary South American civilization named Uros. It gives an overview of sustainable daily practices of the Uros - who live on floating organic hand made islands on the cold waters of Lake Titicaca at 3810 m above sea level in Puno, Peru - and their potential for future innovative developments. The objective of this paper is to highlight the importance of researching the Totora plant’s floating properties, which will give us insights into its possible diverse applications as a floating material of construction. This study bridges science with traditional knowledge, an inspiring lesson for developing innovative ideas. 1 Location: Puno- Peru Figure 1 : Islands located at five kilometers east from Puno port at 3810m above sea level Source: Google earth The Totora plant This paper is about the Totora plant that grows in Titicaca Lake. Its scientific name is Schoenoplectus californicus ssp. tatora. Totora is an aquatic plant which grows in humid places, wetlands, along rivers and lakes. This plant has a long stem (400 cm long approximately) and its stem section has a circular shape (d =1.5 cm aprox). -

Crossing the Ocean on a Reed Sailing Boat

FLAG REPORT 1 ATLANTIC OCEAN EXPEDITION Crossing the Ocean on a Reed Sailing Boat In July 2007, Sabrina Lorenz set sail across the Atlantic with ten others and Wings WorldQuest Flag #3 to prove that intercontinental trade was possible in prehistoric times. Expedition leader Dominique Görlitz invited Sabrina, an experienced scientific scuba diver, and Andrea Müller to be the two women to sail aboard the Abora III, a reed boat similar to those used in predynastic Egypt. Long before Columbus or the Vikings voyaged to the New World, growing evidence indicates that people regularly crossed the Atlantic. Cave drawings from the Magdalene Old Stone Age cultures in France and Spain attest to advanced nautical knowledge. Top: Sabrina holds WWQ Flag #3 on BUILDING AND PROVISIONING AN ANCIENT REPLICA the Abora III in Liberty Harbor, New Jersey. Photo: Milbry Polk Amaya natives, who make reed boats on Lake Titicaca, constructed the hull of the Abora III in Bolivia. When it Above: Drawings from 12,000 BCE in “Cueva del Castillo” in Spain suggest arrived in New Jersey, Sabrina helped build the mast, people had advanced nautical knowl- two cabins, deck, and navigation facilities using only edge. Photo: http://www.abora3.com ancient techniques – wood roped together and held fast with innumerable knots. And taking a cue from the cave paintings, the craft was outfitted with a series of rudders, which allowed greater dexterity in steering. Dominique asked Sabrina to assemble enough food for eleven people to last 60 days at sea. On July 11, the Abora III set sail from New York Harbor with strong winds to the east.