Assessment of the Labour Market & Skills Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5. Education・ Vocational Training Preliminary Study for Iraq Reconstruction Projects in Hashemite Kingdome of Jordan Final Report

5. Education・ Vocational Training Preliminary Study for Iraq Reconstruction Projects in Hashemite Kingdome of Jordan Final Report 5 Education and Vocational Training 5.1 Outline of Education and Vocational Training in Iraq The population in Iraq is estimated at 2.6 million with annual population growth rate of approximately 2.8%. The education system in Iraq showed high performance rate until the early 1980s and it achieved nearly universal primary enrollment in 1980. Thereafter, for more than two decades, the enrollment rate went into a steady decline and the attendance went down at an alarming rate. Out of nearly 15,000 existing school buildings, 80% now require significant restoration. More than 1,000 schools need to be demolished and completely reconstructed. Another 4,600 require major repair based on information from the Ministry of Education. Table 5.1.1 No. of Students by Level of School (excluding higher education) Level of Education No. of Source Students Kindergarten 53,499 MOE and UNICEF Primary school 4,280,602 MOE and UNICEF Secondary education (Intermediate and Preparatory) 1,454,775 MOE, UNICEF, UNESCO and USAID Vocational school 62,841 MOE and UNICEF Teacher training school 66,139 MOE and UNICEF Table 5.1.2 No. of Students by Sex by Level of Education (excluding higher education) Level of Education Sex No. of Students Source Female 26,068(48.73%) MOE and UNICEF Kindergarten Male 27,431(51.27%) Female 1,903,618(44.47%) MOE and UNICEF Primary school Male 2,376,984(55.53%) Secondary education (Intermediate Female 585,937(40.28%) MOE, UNICEF, UNESCO and USAID and Preparatory) Male 868,838(59.72%) Vocational school Female 11,940(19%) MOE and UNICEF Teacher training school Male 50,901(81%) Table 5.1.3 No. -

A Comparative Study Between Internally and Externally Displaced Populations in the Duhok Governorate of Iraq

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive Public Administration & Policy Honors College 5-2018 Healthcare Services for the Displaced: A Comparative Study between Internally and Externally Displaced Populations in the Duhok Governorate of Iraq Shannon Moquin University at Albany, State University of New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_pad Part of the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Moquin, Shannon, "Healthcare Services for the Displaced: A Comparative Study between Internally and Externally Displaced Populations in the Duhok Governorate of Iraq" (2018). Public Administration & Policy. 8. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_pad/8 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Administration & Policy by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moquin 1 Healthcare Services for the Displaced: A Comparative Study between Internally and Externally Displaced Populations in the Duhok Governorate of Iraq An honor’s thesis presented to the Department of Public Policy and Administration University at Albany, State University of New York in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors in Public Policy and Management and graduation from The Honors College Shannon Moquin Research Advisors: Kamiar Alaei, MD, DrPH, MPH, MS, LLM John Schiccitano, MBA May 2018 Moquin 2 Abstract: Although forced displacement is not a new problem, the topic has gained increasing attention due to the Syrian refugee crisis. This paper serves to explore the legal, contextual and practical differences between internally and externally displaced populations. -

The Security Situation in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq IRAQ

IRAQ 14 november 2017 The Security Situation in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq Disclaimer This document was produced by the Information, Documentation and Research Division (DIDR) of the French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons (OFPRA). It was produced with a view to providing information pertinent to the examination of applications for international protection. This document does not claim to be exhaustive. Furthermore, it makes no claim to be conclusive as to the determination or merit of any particular application for international protection. It must not be considered as representing any official position of OFPRA or French authorities. This document was drafted in accordance with the Common EU Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), April 2008 (cf. http://www.refworld.org/docid/48493f7f2.html). It aims to be impartial, and is primarily based on open-source information. All the sources used are referenced, and the bibliography includes full bibliographical references. Consistent care has been taken to cross-check the information presented here. If a particular event, person or organisation is not mentioned in the report, this does not mean that the event has not taken place or that the person or organisation does not exist. Neither reproduction nor distribution of this document is permitted, except for personal use, without the express consent of OFPRA, according to Article L. 335-3 of the French Intellectual Property Code. The Security situation in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq Table of contents 1. Background information ............................................................................... 3 2. Types of threats ........................................................................................... 3 2.1. Turkish bombings ...................................................................................... 3 2.2. Criminality ............................................................................................... -

Full of Stones

Lausanne World Pulse, P.O. Box 794, Wheaton, IL 60189. E-mail: [email protected] A FREE monthly, online magazine that provides you with missions and evangelism news, information and analysis. NOVEMBER 2005 issue WORLD NEWS BRIEFS BELARUS Two months after a regular Sunday morning service of the New Life Church in Minsk was raided by police, a court fined the church’s administrator Vasily Yurevich the equivalent of 160 times the minimum monthly wage for organizing what the court called an “illegal” service. Yurevich told Forum 18 News Service that Judge Natalya Kuznetsova ignored church members’ insistence that he had not organized the service, while the court decision maintained that the judge “believes offender Yurevich is trying to evade responsibility for what has been committed.” This is Yurevich’s second massive fine and he fears further fines in the wake of a recent police raid of a church service. (Forum 18 News, http://www.forum18.org/ Archive.php?article_id=661) BELARUS After spending more than thirteen years in Soviet labor camps for his faith, Pastor Ernst Sabilo has promised that the Belarusian Evangelical Church he leads in Minsk will continue to meet for worship despite the recent liquidation of its legal status by the city court. Belarus’ restrictive 2002 religion law bans unregistered religious activity. The liquidation came a month after the same court liquidated a Calvinist church. Other religious communities which failed to gain re-registration by the deadline also remain uncertain as to the legality of their parishes as well. (Forum 18 News, http://www.forum18.org/ Archive.php?article_id=664 CANADA After serving with Christian Reformed World Missions in the Philippines for nearly a decade, Ontario native Rev. -

The Security Situation of Religious and Ethnic Minorities IRAQ

IRAQ 14 november 2017 The Security situation of religious and ethnic minorities Disclaimer This document was produced by the Information, Documentation and Research Division (DIDR) of the French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons (OFPRA). It was produced with a view to providing information pertinent to the examination of applications for international protection. This document does not claim to be exhaustive. Furthermore, it makes no claim to be conclusive as to the determination or merit of any particular application for international protection. It must not be considered as representing any official position of OFPRA or French authorities. This document was drafted in accordance with the Common EU Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), April 2008 (cf. http://www.refworld.org/docid/48493f7f2.html). It aims to be impartial, and is primarily based on open-source information. All the sources used are referenced, and the bibliography includes full bibliographical references. Consistent care has been taken to cross-check the information presented here. If a particular event, person or organisation is not mentioned in the report, this does not mean that the event has not taken place or that the person or organisation does not exist. Neither reproduction nor distribution of this document is permitted, except for personal use, without the express consent of OFPRA, according to Article L. 335-3 of the French Intellectual Property Code. Iraq: the Security situation of religious and ethnic minorities -

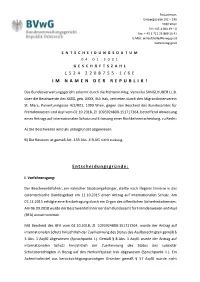

L 5 2 4 2 2 0 8 7

Postadresse: Erdbergstraße 192 – 196 1030 Wien Tel: +43 1 601 49 – 0 Fax: + 43 1 711 23-889 15 41 E-Mail: [email protected] www.bvwg.gv.at ENTSCHEIDUNGSDATUM 0 4 . 0 1 . 2 0 2 1 GESCHÄFTSZAHL L 5 2 4 220 8 7 5 5 - 1/6E IM NAMEN DER REPUBLI K! Das Bundesverwaltungsgericht erkennt durch die Richterin Mag. Veronika SANGLHUBER LL.B. über die Beschwerde des XXXX, geb. XXXX, StA Irak, vertreten durch den MigrantInnenverein St. Marx, Pulverturmgasse 4/2/R01, 1090 Wien, gegen den Bescheid des Bundesamtes für Fremdenwesen und Asyl vom 02.10.2018, Zl. 1093924800-151717364, betreffend Abweisung eines Antrags auf internationalen Schutz und Erlassung einer Rückkehrentscheidung, zu Recht: A) Die Beschwerde wird als unbegründet abgewiesen. B) Die Revision ist gemäß Art. 133 Abs. 4 B-VG nicht zulässig. Entscheidungsgründe : I. Verfahrensgang: Der Beschwerdeführer, ein irakischer Staatsangehöriger, stellte nach illegaler Einreise in das österreichische Bundesgebiet am 12.10.2015 einen Antrag auf internationalen Schutz. Am 07.11.2015 erfolgte eine Erstbefragung durch ein Organ des öffentlichen Sicherheitsdienstes. Am 06.09.2018 wurde der Beschwerdeführer vor dem Bundesamt für Fremdenwesen und Asyl (BFA) einvernommen. Mit Bescheid des BFA vom 02.10.2018, Zl. 1093924800-151717364, wurde der Antrag auf internationalen Schutz hinsichtlich der Zuerkennung des Status des Asylberechtigten gemäß § 3 Abs. 1 AsylG abgewiesen (Spruchpunkt I.). Gemäß § 8 Abs. 1 AsylG wurde der Antrag auf internationalen Schutz hinsichtlich der Zuerkennung des Status des subsidiär Schutzberechtigten in Bezug auf den Herkunftsstaat Irak abgewiesen (Spruchpunkt II.). Ein Aufenthaltstitel aus berücksichtigungswürdigen Gründen gemäß § 57 AsylG wurde nicht - 2 - erteilt (Spruchpunkt III.). -

A Comparative Study on the Dry Canal Future Project in Iraq and the Grand Canal Project in China

Innovative Systems Design and Engineering www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1727 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2871 (Online) Vol.6, No.5, 2015 A Comparative Study on the Dry Canal Future Project in Iraq and the Grand Canal Project in China Ghassan Hassan Abdul Hadi (Corresponding author) School of Architecture & Urban Planning, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan City, Chi E-mail: [email protected] Dr. Tan Gangyi School of Architecture & Urban Planning, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan City, China ,Ph.D. (SCUT), Professor and vice Dean, School of Architecture & Urban Planning, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, No.1037, Luoyu Road, Wuhan, P.R. China 430074 E-mail: [email protected] Duraid G. Hasan School of Civil Engineering and Mechanics, Huazhong University of science and Technology, Wuhan City, China E-mail: [email protected] Gelareh Sadeghi School of Architecture & Urban Planning, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan City, China E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Each country has its own political goal and strategic objective in manner of economic development and each is free to do what it wants in order to grow its economy to improve the living conditions of its people. In that way, a key consideration for Iraq is access to the sea and world trade. This desire is guiding to a major part of this larger vision that it calls ‘Dry Canal Project’ which will allow for transport of goods between the north and the south of the world quickly, cheaply and safely. It is expected that this project will enhance the transportation industry of goods in general, not only in Iraq, but on the world's level as well, and also will support the Iraqi national economy. -

Suggested Format of Humanitarian Country

Year: 2017 Ref. Ares(2017)4983615 - 12/10/2017 Last update: 01/10/17 Version 3 HUMANITARIAN IMPLEMENTATION PLAN (HIP) IRAQ The activities proposed hereafter are still subject to the adoption of the financing decision ECHO/WWD/ BUD/2017/01000 AMOUNT: EUR 82.5 million The present Humanitarian Implementation Plan (HIP) was prepared on the basis of financing decision ECHO/WWD/BUD/2017/01000 (Worldwide Decision) and the related General Guidelines for Operational Priorities on Humanitarian Aid (Operational Priorities). The purpose of the HIP and its annex is to serve as a communication tool for ECHO's partners and to assist in the preparation of their proposals. The provisions of the Worldwide Decision and the General Conditions of the Agreement with the European Commission shall take precedence over the provisions in this document. 0. MAJOR CHANGES SINCE PREVIOUS VERSION OF THE HIP Modification 2 – October 2017 Massive urgent humanitarian needs remain and need to be covered in 2017. The humanitarian consequences of the Mosul operations have surpassed the worst-case scenario estimated by the UN and humanitarian partners. Over 1 000 000 have been displaced by the conflict, out of which over 700 000 remain displaced. Military operations to retake Telafar from the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) begun on 20 August; those to retake West Anbar and Hawija started on 16 and 21 September, respectively. Thousands of people have fled conflict areas in locations where current humanitarian capacities need to be urgently increased. Displacement from western Anbar increased sharply in the second half of September, rising four-fold in a week. -

Iraqi Migration to Europe in 2016: Profiles, Drivers and Return

INCLUDE AN IMAGE (MAP OR PICTURE) Format Cover Page: See Report Drafting Guidelines Image: See REACH Photo Guidelines IRAQI MIGRATION TO EUROPE IN 2016: PROFILES, DRIVERS AND RETURN IRAQ / GREECE REPORT JUNE 2017 Iraqi Migration to Europe in 2016: Profiles, Drivers and Return Cover Photo: © Roberto Forin, 2016 About REACH REACH is a joint initiative of two international non-governmental organisations - ACTED and IMPACT Initiatives - and the UN Operational Satellite Applications Programme (UNOSAT). REACH’s mission is to strengthen evidence- based decision making by aid actors through efficient data collection, management and analysis before, during and after an emergency. By doing so, REACH contributes to ensuring that communities affected by emergencies receive the support they need. All REACH activities are conducted in support to and within the framework of inter- agency aid coordination mechanisms. For more information please visit our website: www.reach-initiative.org. You can contact us directly at: [email protected] and follow us on Twitter @REACH_info. 1 Iraqi Migration to Europe in 2016: Profiles, Drivers and Return EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background The number of Iraqis migrating irregularly to Europe drastically increased between 2014 and 2016. In 2015, 91,769 Iraqis arrived in Europe through the Eastern Mediterranean route, compared to only 1,023 in 2014.1 At the same time, since 2014, return migration from Europe to Iraq has substantially increased: between 2014 and 2016, the number of returnees from Europe to Iraq through the International Organisation for Migration’s (IOM) Assisted Voluntary Return Scheme has increased tenfold (from 1,280 to 12,776)2 and many more anecdotal accounts of individual returns exist.3 These migration flows – from Iraq to Europe and the increased number of returnees from Europe to their country of origin – are inherently complex and multi-faceted. -

R5 4-Foreign-Policy

12 October 2017 SMA Reach-back Report Evolution of US Foreign Policy in Middle East Question R5.4: How should United States foreign policy evolve in the region post-Islamic State of Iraq and Syria? What are the dynamics in the region and what will be the implications of this for the USG? Contributors Hala Abdulla, Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning, Marine Corps University; Gawdat Bahgat, Near East South Asia Center for Strategic Studies, National Defense University; Perry CammacK, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; Patricia DeGennaro, TRADOC G27; Vernie Liebl, Center for Advanced Operational Culture Learning, Marine Corps University; Diane Maye, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University; Spencer Meredith, National Defense University; Paul Rogers, Bradford University; Daniel Serwer, Middle East Institute; Martin StyszynsKi, Adam MicKiewicz University; TRADOC G2 Global Cultural Knowledge Network (GCKN) Executive Summary Patricia DeGennaro, TRADOC G-27 & Sarah Canna, NSI US foreign policy maKers struggle to find the right balance in supporting US interests in the Middle East (Abdulla, Bahgat, DeGennaro, Liebl, Maye, Rogers, Serwer, StyszynsKi). The unbalanced policies, those focusing solely on defense or certain allied interests, while marginalizing diplomacy and development, are diminishing trust in the US and decreasing its influence—challenging US ability to maintain global stability. Historically, US interventions in the region have caused instability and competition between regional Middle Eastern states leaving many of the weaKer parties—Libya, Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, Yemen, and the Palestinian territories—targets for interference from the Arab Gulf countries, Iran, violent extremists, and those who thrive on internal conflict (DeGennaro). As a result, the region, and more recently the world, has been plagued with ideological radical extremists who have used a perverse form of the religion of Islam to violently project their discontent and anger on populations. -

THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE of the UNIVERSITY of CHICAGO

oi.uchicago.edu THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE of THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION Edited by JAMES HENRY BREASTED with the assistance of THOMAS GEORGE ALLEN oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu I. PLANO-CONVEX BRICKS AND THE METHODS OF THEIR EMPLOYMENT II. THE TREATMENT OF CLAY TABLETS IN THE FIELD oi.uchicago.edu THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS THE BAKER & TAYLOR COMPANY NEW YORK THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON THE MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA TOKYO, OSAKA, KYOTO, FUKUOKA, SENDAI THE COMMERCIAL PRESS, LIMITED SHANGHAI oi.uchicago.edu THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE of THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION, NO. 7 I. PLANO-CONVEX BRICKS AND THE METHODS OF THEIR EMPLOYMENT II. THE TREATMENT OF CLAY TABLETS IN THE FIELD By P. DELOUGAZ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu COPYRIGHT 1933 BY THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PUBLISHED DECEMBER 1933 COMPOSED AND PRINTED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, U.S.A. oi.uchicago.edu FOREWORD In the present volume Mr. Delougaz publishes the results of some research work which cannot well be embodied in an account of the excavations proper and which we believe nevertheless to be of value. His first essay deals with plano-convex bricks and the methods of their employment, the second with the treatment of tablets in the field. PART I Until a few years ago plano-convex bricks were regarded as the characteristic building material of early Sumerian times. But when Dr. Jordan published his discoveries from the archaic layers of Warka (Erech) in 1929-30, he drew attention to the very definite time to which the use of plano-convex bricks appeared to be limited. -

Important Notice This Offering Is Available Only

IMPORTANT NOTICE THIS OFFERING IS AVAILABLE ONLY TO INVESTORS WHO ARE EITHER (1) QUALIFIED INSTITUTIONAL BUYERS (“QIBs”) UNDER RULE 144A OR (2) NON-U.S. PERSONS OUTSIDE OF THE U.S. (AND, IF INVESTORS ARE RESIDENT IN A MEMBER STATE OF THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AREA, A QUALIFIED INVESTOR). IMPORTANT: You must read the following before continuing. The following applies to the Prospectus following this page, and you are therefore advised to read this carefully before reading, accessing or making any other use of the Prospectus. In accessing the Prospectus, you agree to be bound by the following terms and conditions, including any modifications to them any time you receive any information from us as a result of such access. NOTHING IN THIS ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES AN OFFER OF SECURITIES FOR SALE IN ANY JURISDICTION WHERE IT IS UNLAWFUL TO DO SO. THE SECURITIES HAVE NOT BEEN, AND WILL NOT BE, REGISTERED UNDER THE U.S. SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 (THE “SECURITIES ACT”), OR THE SECURITIES LAWS OF ANY STATE OF THE U.S. OR OTHER JURISDICTION AND THE SECURITIES MAY NOT BE OFFERED OR SOLD WITHIN THE U.S. OR TO, OR FOR THE ACCOUNT OR BENEFIT OF, U.S. PERSONS (AS DEFINED IN REGULATION S UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT), EXCEPT PURSUANT TO AN EXEMPTION FROM, OR IN A TRANSACTION NOT SUBJECT TO, THE REGISTRATION REQUIREMENTS OF THE SECURITIES ACT AND APPLICABLE LAWS OF OTHER JURISDICTIONS. THE FOLLOWING PROSPECTUS MAY NOT BE FORWARDED OR DISTRIBUTED TO ANY OTHER PERSON AND MAY NOT BE REPRODUCED IN ANY MANNER WHATSOEVER. ANY FORWARDING, DISTRIBUTION OR REPRODUCTION OF THIS DOCUMENT IN WHOLE OR IN PART IS UNAUTHORIZED.