R5 4-Foreign-Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Offensive Against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area Near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS

June 23, 2016 Offensive against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters at the western entrance to the city of Manbij (Fars, June 18, 2016). Overview 1. On May 31, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-dominated military alliance supported by the United States, initiated a campaign to liberate the northern Syrian city of Manbij from ISIS. Manbij lies west of the Euphrates, about 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) south of the Syrian-Turkish border. In the three weeks since the offensive began, the SDF forces, which number several thousand, captured the rural regions around Manbij, encircled the city and invaded it. According to reports, on June 19, 2016, an SDF force entered Manbij and occupied one of the key squares at the western entrance to the city. 2. The declared objective of the ground offensive is to occupy Manbij. However, the objective of the entire campaign may be to liberate the cities of Manbij, Jarabulus, Al-Bab and Al-Rai, which lie to the west of the Euphrates and are ISIS strongholds near the Turkish border. For ISIS, the loss of the area is liable to be a severe blow to its logistic links between the outside world and the centers of its control in eastern Syria (Al-Raqqah), Iraq (Mosul). Moreover, the loss of the region will further 112-16 112-16 2 2 weaken ISIS's standing in northern Syria and strengthen the military-political position and image of the Kurdish forces leading the anti-ISIS ground offensive. -

The Culmination of Tradition-Based Tafsīr the Qurʼān Exegesis Al-Durr Al-Manthūr of Al-Suyūṭī (D. 911/1505)

The Culmination of Tradition-based Tafsīr The Qurʼān Exegesis al-Durr al-manthūr of al-Suyūṭī (d. 911/1505) by Shabir Ally A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto © Copyright by Shabir Ally 2012 The Culmination of Tradition-based Tafsīr The Qurʼān Exegesis al-Durr al-manthūr of al-Suyūṭī (d. 911/1505) Shabir Ally Doctor of Philosophy Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto 2012 Abstract This is a study of Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī’s al-Durr al-manthūr fi-l-tafsīr bi-l- ma’thur (The scattered pearls of tradition-based exegesis), hereinafter al-Durr. In the present study, the distinctiveness of al-Durr becomes evident in comparison with the tafsīrs of al- a arī (d. 310/923) and I n Kathīr (d. 774/1373). Al-Suyūṭī surpassed these exegetes by relying entirely on ḥadīth (tradition). Al-Suyūṭī rarely offers a comment of his own. Thus, in terms of its formal features, al-Durr is the culmination of tradition- based exegesis (tafsīr bi-l-ma’thūr). This study also shows that al-Suyūṭī intended in al-Durr to subtly challenge the tradition- ased hermeneutics of I n Taymīyah (d. 728/1328). According to Ibn Taymīyah, the true, unified, interpretation of the Qurʼān must be sought in the Qurʼān ii itself, in the traditions of Muḥammad, and in the exegeses of the earliest Muslims. Moreover, I n Taymīyah strongly denounced opinion-based exegesis (tafsīr bi-l-ra’y). -

Eksistensi Khawarij Menurut Pemikiran Fazlur Rahman

EKSISTENSI KHAWARIJ MENURUT PEMIKIRAN FAZLUR RAHMAN SKRIPSI Diajukan Untuk Melengkapi Tugas-tugas dan Memenuhi Syarat-syarat Guna Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Agama Islam (S.Ag). Dalam Ilmu Ushuluddin Oleh: IDWIN SAPUTRA NPM: 1531010041 Prodi: Aqidah Filsafat Islam FAKULTAS USHULUDDIN DAN STUDI AGAMA UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI RADEN INTAN LAMPUNG 1440 H / 2019 M ABSTRAK EKSISTENSI KHAWARIJ MENURUT PEMIKIRAN FAZLUR RAHMAN Oleh: Idwin Saputra Khawarij adalah sekelompok orang yang keluar dari barisan Ali Ibn Abi Thalib, di karenakan mereka tidak menerima atas tahkim (arbitrse) yang diterima oleh Khalifah Ali Ibn Abi Thalib dengan Mu’awiyah dalam perkara Khilafah (pemimpin). Dan orang-orang Khawarij ini dicirikan dengan watak yang keras, karena asal usul mereka dari masyarakat badawi dan gurun pasir yang tandus. dan menurut mereka orang yang tidak sepaham dengan mereka dianggap Kafir, baik itu pelaku dosa besar maupun kecil. Karena menurut mereka yang paling benar adalah apa yang sudah ditentukan oleh Allah dan apa yang di dalam Al-qur’an sesuai dengan apa yang menjadi semboyan mereka yakni : La HukmaIlaAllah“ tidak ada hukum kecuali hukum Allah,”. Khawarij ini sebenarnya sudah hilang sesuai dengan sejarah, hanya golongan Al- Ibadiyah yang masih ada sampai saat ini terletak di bagian Zanzibar, Afrika Utara, Omman dan Arabiah Selatan. Kemudian Khawarij ini juga ada yang ekstrem dan yang moderat. Menurut Fazlur Rahman nama Khawarij tak berimplikasi bid’ah dari segi doktrin, melainkan sebatas pemberontak atau pelaku revolusi. Adapun rumusan masalah dalam penelitian ini adalah: Bagaimana eksistensi khawarij saat ini. Bagaimana Khawarij menurut pemikiran Fazlur Rahman. Adapun tujuan penelitan ini adalah untuk mengetahui bagaimaman eksistensi Khawarij saat ini dan bagaimana Khawarij Menurut pemikiran Fazlur Rahman. -

University of Lo Ndo N Soas the Umayyad Caliphate 65-86

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SOAS THE UMAYYAD CALIPHATE 65-86/684-705 (A POLITICAL STUDY) by f Abd Al-Ameer 1 Abd Dixon Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philoso] August 1969 ProQuest Number: 10731674 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731674 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2. ABSTRACT This thesis is a political study of the Umayyad Caliphate during the reign of f Abd a I -M a lik ibn Marwan, 6 5 -8 6 /6 8 4 -7 0 5 . The first chapter deals with the po litical, social and religious background of ‘ Abd al-M alik, and relates this to his later policy on becoming caliph. Chapter II is devoted to the ‘ Alid opposition of the period, i.e . the revolt of al-Mukhtar ibn Abi ‘ Ubaid al-Thaqafi, and its nature, causes and consequences. The ‘ Asabiyya(tribal feuds), a dominant phenomenon of the Umayyad period, is examined in the third chapter. An attempt is made to throw light on its causes, and on the policies adopted by ‘ Abd al-M alik to contain it. -

SYRIA the Constitution and Other Laws And

SYRIA The constitution and other laws and policies protect religious freedom; however, the government imposed restrictions on this right. While there is no official state religion, the constitution requires that the president be Muslim and stipulates that Islamic jurisprudence is a principal source of legislation. The constitution provides for freedom of faith and religious practice so long as religious rites do not disturb the public order; however, the government restricted full freedom of practice on some religious matters, including proselytizing. Although the government generally enforced legal and policy protections of religious freedom for most Syrians, including the Christian minority, it continued to prosecute individuals for membership in the Muslim Brotherhood, Salafist groups, and other faith communities that it deemed to be extreme. The Syrian government outlaws not only Muslim extremist groups, but also Jehovah's Witnesses. In addition the government continued to monitor the activities of all organizations, including religious groups, and to discourage proselytizing, which it deemed a threat to relations among and within different faiths. There was no change in the status of respect for religious freedom by the government during the reporting period. There were reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious affiliation, belief, or practice. There were occasional reports of tensions among religious groups, some of which were attributable to economic rivalries but exacerbated by religious differences. Muslim converts to Christianity were sometimes forced to leave their place of residence due to societal pressure. The U.S. government discusses religious freedom with civil society, religious leaders, and adherents of religious groups as part of its overall policy to promote human rights. -

Radicalization of Faith Concept in the School of Islam: Study of Khawarij and Muktazilah

Asian Social Science; Vol. 14, No. 7; 2018 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Radicalization of Faith Concept in the School of Islam: Study of Khawarij and Muktazilah Ramli Nur1 1 Faculty of Social Science, Universitas Negeri Medan, Indonesia Correspondence: Ramli Nur, Jl. Willem Iskandar Pasar V Medan Estate, North Sumatera, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 29, 2018 Accepted: June 2, 2018 Online Published: June 22, 2018 doi:10.5539/ass.v14n7p77 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v14n7p77 Abstract The Radicalism is an idea or school that pursues revolution or social and political reforms in a tough or drastic way. The school of khawarij and muktazilah (two groups) have marked the history of Islamic thought about the concept of faith. The coloration shown tends to represent extremes in understanding the concept of faith. In general, it makes charitable deeds or branch teachings (furu') as part of the nature of faith. That leads to them getting caught in judging faith based on it being black or white between mukmin and kafir. Therefore the perpetrators of the great sins are punished out of Islam. Not merely categorization, but they also fighting and justifying of Muslims whom they consider to have abandoned the teachings of birth or violated something prohibited on the teaching of birth. Such as of these understandings have mutated in the long history of the Muslims into the various nisbat mentions and often manipulate the religious as legitimacy for destructive radical actions. That is why this idea is quite dangerous not only at the beginning of its appearance but also in the current era to watch out for. -

Assessment of the Labour Market & Skills Analysis

Assessment of the Labour Market & Skills Analysis Iraq and Kurdistan Region-Iraq Information and Communication Assessment of the Labour Market & Skills Analysis Iraq and Kurdistan Region-Iraq Information and Communication Published by: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7. place of Fotenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Office for Iraq UN Compound, International Zone, Baghdad, Iraq Education Sector E-mail: [email protected] UNESCO 2019 All rights reserved Designed by: Alaa Al Khayat UNESCO and Sustainable Development Goals UNESCO actively helped to frame the Education 2030 agenda which is encapsulated in UNESCO’s work and Sustainable Development Goal 4. The Incheon Declaration, adopted at the World Education Forum in Korea in May 2015, entrusted UNESCO to lead and coordinate the Education 2030 agenda through guidance and technical support to governments and partners on how to turn commitments into action. Acknowledgements This report is the result of the strong and collaborative relationship between the Government of Iraq and Kurdistan Region-Iraq (KR-I), European Union, and UNESCO. The report was drafted by David Chang, Rory Robertshaw and Alison Schmidt under the guidance of Dr. Hamid K. Ahmed, Louise Haxthausen and the Steering Committee Members of the TVET Reform Programme for Iraq and KR-I. The Central Statistical Organization (CSO) and the Kurdistan Regional Statistics Office (KRSO) provided valuable feedback and contributions to which -

Arab Nationalism in Interwar Period Iraq: a Descriptive Analysis of Sami Shawkat’S Al-Futuwwah Youth Movement Saman Nasser

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Fall 2018 Arab nationalism in interwar period Iraq: A descriptive analysis of Sami Shawkat’s al-Futuwwah youth movement Saman Nasser Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the Intellectual History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Nasser, Saman, "Arab nationalism in interwar period Iraq: A descriptive analysis of Sami Shawkat’s al-Futuwwah youth movement" (2018). Masters Theses. 587. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/587 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Arab Nationalism in Interwar Period Iraq: A Descriptive Analysis of Sami Shawkat’s al- Futuwwah Youth Movement Saman Nasser A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Department of History December 2018 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair: Dr. Shah Mahmoud Hanifi Committee Members/Readers: Dr. Timothy J. Fitzgerald Dr. Steven W. Guerrier Dedication To my beloved parents: Rafid Nasser and Samhar Abed. You are my Watan. ii Acknowledgements My sincere personal and intellectual gratitude goes to my thesis director, Professor Shah Mahmoud Hanifi. Professor Hanifi’s ‘bird-eye’ instructions, care, encouragement, patience and timely football analogies (to clarify critical points) made the production of the thesis possible. -

A Comparative Study Between Internally and Externally Displaced Populations in the Duhok Governorate of Iraq

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive Public Administration & Policy Honors College 5-2018 Healthcare Services for the Displaced: A Comparative Study between Internally and Externally Displaced Populations in the Duhok Governorate of Iraq Shannon Moquin University at Albany, State University of New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_pad Part of the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Moquin, Shannon, "Healthcare Services for the Displaced: A Comparative Study between Internally and Externally Displaced Populations in the Duhok Governorate of Iraq" (2018). Public Administration & Policy. 8. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_pad/8 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Administration & Policy by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moquin 1 Healthcare Services for the Displaced: A Comparative Study between Internally and Externally Displaced Populations in the Duhok Governorate of Iraq An honor’s thesis presented to the Department of Public Policy and Administration University at Albany, State University of New York in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors in Public Policy and Management and graduation from The Honors College Shannon Moquin Research Advisors: Kamiar Alaei, MD, DrPH, MPH, MS, LLM John Schiccitano, MBA May 2018 Moquin 2 Abstract: Although forced displacement is not a new problem, the topic has gained increasing attention due to the Syrian refugee crisis. This paper serves to explore the legal, contextual and practical differences between internally and externally displaced populations. -

Bektashi Order - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Personal Tools Create Account Log In

Bektashi Order - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Personal tools Create account Log in Namespaces Views Article Read Bektashi OrderTalk Edit From Wikipedia, the freeVariants encyclopedia View history Main page More TheContents Bektashi Order (Turkish: Bektaşi Tarikatı), or the ideology of Bektashism (Turkish: Bektaşilik), is a dervish order (tariqat) named after the 13th century Persian[1][2][3][4] Order of Bektashi dervishes AleviFeatured Wali content (saint) Haji Bektash Veli, but founded by Balim Sultan.[5] The order is mainly found throughout Anatolia and the Balkans, and was particularly strong in Albania, Search BulgariaCurrent events, and among Ottoman-era Greek Muslims from the regions of Epirus, Crete and Greek Macedonia. However, the Bektashi order does not seem to have attracted quite as BektaşiSearch Tarikatı manyRandom adherents article from among Bosnian Muslims, who tended to favor more mainstream Sunni orders such as the Naqshbandiyya and Qadiriyya. InDonate addition to Wikipedia to the spiritual teachings of Haji Bektash Veli, the Bektashi order was later significantly influenced during its formative period by the Hurufis (in the early 15th century),Wikipedia storethe Qalandariyya stream of Sufism, and to varying degrees the Shia beliefs circulating in Anatolia during the 14th to 16th centuries. The mystical practices and rituals of theInteraction Bektashi order were systematized and structured by Balım Sultan in the 16th century after which many of the order's distinct practices and beliefs took shape. A largeHelp number of academics consider Bektashism to have fused a number of Shia and Sufi concepts, although the order contains rituals and doctrines that are distinct unto itself.About Throughout Wikipedia its history Bektashis have always had wide appeal and influence among both the Ottoman intellectual elite as well as the peasantry. -

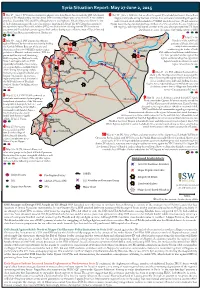

SYR SITREP Map May 27-June 2 2015

Syria Situation Report: May 27-June 2, 2015 1 May 27 – June 1: YPG forces continued to advance west from Ras al-Ayn towards the ISIS-held border 6 May 29 – June 2: ISIS launched an oensive against JN and rebel positions in the northern crossing of Tel Abyad, seizing over two dozen ISIS-controlled villages with support from U.S.-led coalition Aleppo countryside, seizing the town of Soran Azaz and several surrounding villages in a airstrikes. Meanwhile, YPG and FSA-aliated rebels in the Euphrates Volcano Operations Room in Ayn multi-pronged attack which included an SVBIED attack. In response, JN and numerous al-Arab canton announced the start of an oensive targeting Tel Abyad. e YPG denied accusations by Aleppo-based rebel groups deployed large numbers of reinforcements to the area. Clashes are the opposition Syrian National Coalition (SNC) and local activists claiming that the YPG conducted still ongoing amidst reported regime airstrikes in the area, which prompted the U.S. State executions and forced displacements against Arab civilians during recent oensives west of Ras al-Ayn and Department to accuse the regime of providing support to ISIS. on Abdul Aziz Mountain southwest of Hasaka city. Qamishli 7 May 27 – 30: 2 May 30 – June 2: ISIS launched an oensive Ayn al-Arab Residents of the rebel-held Ras al-Ayn against Hasaka City from three axes, heavily shelling 6 portions of Dera’a City held the Kawkab Military Base east of the city and 1 multiple demonstrations detonating at least two SVBIEDs against regime 10 Hasakah condemning the leaders of both FSA-aliated and Islamist rebel factions positions in Hasaka’s southern outskirts. -

The Security Situation in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq IRAQ

IRAQ 14 november 2017 The Security Situation in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq Disclaimer This document was produced by the Information, Documentation and Research Division (DIDR) of the French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless Persons (OFPRA). It was produced with a view to providing information pertinent to the examination of applications for international protection. This document does not claim to be exhaustive. Furthermore, it makes no claim to be conclusive as to the determination or merit of any particular application for international protection. It must not be considered as representing any official position of OFPRA or French authorities. This document was drafted in accordance with the Common EU Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), April 2008 (cf. http://www.refworld.org/docid/48493f7f2.html). It aims to be impartial, and is primarily based on open-source information. All the sources used are referenced, and the bibliography includes full bibliographical references. Consistent care has been taken to cross-check the information presented here. If a particular event, person or organisation is not mentioned in the report, this does not mean that the event has not taken place or that the person or organisation does not exist. Neither reproduction nor distribution of this document is permitted, except for personal use, without the express consent of OFPRA, according to Article L. 335-3 of the French Intellectual Property Code. The Security situation in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq Table of contents 1. Background information ............................................................................... 3 2. Types of threats ........................................................................................... 3 2.1. Turkish bombings ...................................................................................... 3 2.2. Criminality ...............................................................................................