Union Calendar No. 210 104Th Congress, 1St Session – – – – – – – – – – – – House Report 104–435

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Union Calendar No. 481 104Th Congress, 2D Session – – – – – – – – – – – – House Report 104–879

1 Union Calendar No. 481 104th Congress, 2d Session ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± House Report 104±879 REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES DURING THE ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS PURSUANT TO CLAUSE 1(d) RULE XI OF THE RULES OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES JANUARY 2, 1997.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 36±501 WASHINGTON : 1997 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois, Chairman 1 CARLOS J. MOORHEAD, California JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., PATRICIA SCHROEDER, Colorado Wisconsin BARNEY FRANK, Massachusetts BILL MCCOLLUM, Florida CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York GEORGE W. GEKAS, Pennsylvania HOWARD L. BERMAN, California HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina RICH BOUCHER, Virginia LAMAR SMITH, Texas JOHN BRYANT, Texas STEVEN SCHIFF, New Mexico JACK REED, Rhode Island ELTON GALLEGLY, California JERROLD NADLER, New York CHARLES T. CANADY, Florida ROBERT C. SCOTT, Virginia BOB INGLIS, South Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia XAVIER BECERRA, California STEPHEN E. BUYER, Indiana JOSEÂ E. SERRANO, New York 2 MARTIN R. HOKE, Ohio ZOE LOFGREN, California SONNY BONO, California SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas FRED HEINEMAN, North Carolina MAXINE WATERS, California 3 ED BRYANT, Tennessee STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MICHAEL PATRICK FLANAGAN, Illinois BOB BARR, Georgia ALAN F. COFFEY, JR., General Counsel/Staff Director JULIAN EPSTEIN, Minority Staff Director 1 Henry J. Hyde, Illinois, elected to the Committee as Chairman pursuant to House Resolution 11, approved by the House January 5 (legislative day of January 4), 1995. -

Union Calendar No. 464 104Th Congress, 2Nd Session –––––––––– House Report 104–857

1 Union Calendar No. 464 104th Congress, 2nd Session ±±±±±±±±±± House Report 104±857 YEAR 2000 COMPUTER SOFTWARE CONVER- SION: SUMMARY OF OVERSIGHT FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS SIXTEENTH REPORT BY THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT SEPTEMBER 27, 1996.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 27±317 CC WASHINGTON : 1996 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT WILLIAM F. CLINGER, JR., Pennsylvania, Chairman BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, New York CARDISS COLLINS, Illinois DAN BURTON, Indiana HENRY A. WAXMAN, California J. DENNIS HASTERT, Illinois TOM LANTOS, California CONSTANCE A. MORELLA, Maryland ROBERT E. WISE, JR., West Virginia CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut MAJOR R. OWENS, New York STEVEN SCHIFF, New Mexico EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida JOHN M. SPRATT, JR., South Carolina WILLIAM H. ZELIFF, JR., New Hampshire LOUISE MCINTOSH SLAUGHTER, New JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York York STEPHEN HORN, California PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania JOHN L. MICA, Florida GARY A. CONDIT, California PETER BLUTE, Massachusetts COLLIN C. PETERSON, Minnesota THOMAS M. DAVIS, Virginia KAREN L. THURMAN, Florida DAVID M. MCINTOSH, Indiana CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York RANDY TATE, Washington THOMAS M. BARRETT, Wisconsin DICK CHRYSLER, Michigan BARBARA-ROSE COLLINS, Michigan GIL GUTKNECHT, Minnesota ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana Columbia WILLIAM J. MARTINI, New Jersey JAMES P. MORAN, Virginia JOE SCARBOROUGH, Florida GENE GREEN, Texas JOHN B. SHADEGG, Arizona CARRIE P. MEEK, Florida MICHAEL PATRICK FLANAGAN, Illinois CHAKA FATTAH, Pennsylvania CHARLES F. BASS, New Hampshire BILL BREWSTER, Oklahoma STEVEN C. LATOURETTE, Ohio TIM HOLDEN, Pennsylvania MARSHALL ``MARK'' SANFORD, South ELIJAH CUMMINGS, Maryland Carolina ÐÐÐ ROBERT L. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 141 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, APRIL 7, 1995 No. 65 House of Representatives The House met at 11 a.m. and was PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE DESIGNATING THE HONORABLE called to order by the Speaker pro tem- The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the FRANK WOLF AS SPEAKER PRO pore [Mr. BURTON of Indiana]. TEMPORE TO SIGN ENROLLED gentleman from New York [Mr. SOLO- BILLS AND JOINT RESOLUTIONS f MON] come forward and lead the House in the Pledge of Allegiance. THROUGH MAY 1, 1995 DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO Mr. SOLOMON led the Pledge of Alle- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- TEMPORE giance as follows: fore the House the following commu- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the nication from the Speaker of the House fore the House the following commu- United States of America, and to the Repub- of Representatives: nication from the Speaker. lic for which it stands, one nation under God, WASHINGTON, DC, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. April 7, 1995. WASHINGTON, DC, I hereby designate the Honorable FRANK R. April 7, 1995. f WOLF to act as Speaker pro tempore to sign I hereby designate the Honorable DAN BUR- enrolled bills and joint resolutions through TON to act as Speaker pro tempore on this MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE May 1, 1995. day. NEWT GINGRICH, NEWT GINGRICH, A message from the Senate by Mr. Speaker of the House of Representatives. -

View Entire Issue in Pdf Format

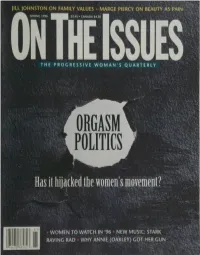

JILL JOHNSTON ON FAMILY VALUES MARGE PIERCY ON BEAUTY AS PAIN SPRING 1996 $3,95 • CANADA $4.50 THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY POLITICS Has it hijackedthe women's movement? WOMEN TO WATCH IN '96 NEW MUSIC: STARK RAVING RAD WHY ANNIE (OAKLEY) GOT HER GUN 7UU70 78532 The Word 9s Spreading... Qcaj filewsfrom a Women's Perspective Women's Jrom a Perspective Or Call /ibout getting yours At Home (516) 696-99O9 SPRING 1996 VOLUME V • NUMBER TWO ON IKE ISSUES THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY features 18 COVER STORY How Orgasm Politics Has Hi j acked the Women's Movement SHEILAJEFFREYS Why has the Big O seduced so many feminists—even Ms.—into a counterrevolution from within? 22 ELECTION'96 Running Scared KAY MILLS PAGE 26 In these anxious times, will women make a difference? Only if they're on the ballot. "Let the girls up front!" 26 POP CULTURE Where Feminism Rocks MARGARET R. SARACO From riot grrrls to Rasta reggae, political music in the '90s is raw and real. 30 SELF-DEFENSE Why Annie Got Her Gun CAROLYN GAGE Annie Oakley trusted bullets more than ballots. She knew what would stop another "he-wolf." 32 PROFILE The Hot Politics of Italy's Ice Maiden PEGGY SIMPSON At 32, Irene Pivetti is the youngest speaker of the Italian Parliament hi history. PAGE 32 36 ACTIVISM Diary of a Rape-Crisis Counselor KATHERINE EBAN FINKELSTEIN Italy's "femi Newtie" Volunteer work challenged her boundaries...and her love life. 40 PORTFOLIO Not Just Another Man on a Horse ARLENE RAVEN Personal twists on public art. -

Congress of the 33Mteb H>Tates( Ehhiil"

WILLIAM F. CLINGER, PENNSYLVANIA CARDISS COLLINS, ILLINOIS CHAIRMAN RANKING MINORITY MEMBER BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, NEW YORK , „ ' , HENRYA. WAXMAN,CALIFORNIA DAN INDIANA ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS tomlantos, J. DENNIS HASTERT, ILLINOIS ROBERT E. WISE, WEST VIRGINIA CONSTANCE A. MORELLA, MARYLAND CHRISTOPHER SHAYS,CONNECTICUT STEVEN SCHIFF, NEW MEXICO Congress ■* H>tates( EHHiiL". of the york 33mteb Louise Mcintosh slaughter,new ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, FLORIDA WILLIAM H. ZELIFF, JR., NEW HAMPSHIRE ** __, PAUL E.KANJORSKI, PENNSYLVANIA JOHN M. McHUGH,NEW YORK STEPHEN HORN,CALIFORNIA $ou*e of »epre*entattbe* COLLIN C.PETERSON, MINNESOTA JOHNL. MICA, FLORIDA KARENL. THURMAN,FLORIDA PETER BLUTE, MASSACHUSETTS THOMAS M. DAVIS, VIRGINIA COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT DAVID M. McINTOSH, INDIANA BARBARA-ROSE COLLINS, MICHIGAN JON D. FOX, PENNSYLVANIA 2157 Rayburn House Building 1 dc RANDYTATE,WASHINGTON Office S^SSNSSS DICK CHRYSLER, MICHIGAN GENE GREEN, TEXAS p GIL GUTKNECHT, MINNESOTA Washington, DC 20515-6143 CARRIE MEEK> Florida MARK E. SOUDER, INDIANA CHAKA FATTAH,PENNSYLVANIA WILLIAM J. MARTINI,NEW JERSEY BILLK. BREWSTER, OKLAHOMA JOE SCARBOROUGH,FLORIDA TIM HOLDEN,PENNSYLVANIA JOHNSHADEGG,ARIZONA MICHAEL PATRICK FLANAGAN, ILLINOIS CHARLES F. BASS, NEW HAMPSHIRE STEVE C. OHIO BERNARDSANDERS, VERMONT MARSHALL "MARK" SANFORD, SOUTH CAROLINA INDEPENDENT ROBERT L. EHRLICH, JR., MARYLAND MAJORITY—<2O2) 225-5074 September 13, 1996 MINORITY—(2O2) 225-5051 Dr. Edward Feigenbaum Chief Scientist U.S. Air Force Dear Dr. Feigenbaum: On behalf of the Committee on Government Reform and Oversight and the U.S. General Accounting Office, we want to thank you for your excellent keynote address during our September 5, 1996 symposium on "Exploring Expert Systems Technology: A Congressional Symposium on Technology and Productivity in Government." Your remarks set the stage for making the symposium a success. -

Fall 2010 • Volume 95 • Number 2

University of Maryland Fall 2010 • Volume 95 • Number 2 aking a D M if fe r e n c GLOBAL e HEALTH Bulletin Editorial Board Joseph S. McLaughlin, ’56 Chairman MedicineBulletin Roy Bands, ’84 University of Maryland Medical Alumni Association & School of Medicine Frank M. Calia, MD, MACP Nelson H. Goldberg, ’73 Donna S. Hanes, ’92 Joseph M. Herman, ’00 features Harry C. Knipp, ’76 Morton D. Kramer, ’55 Morton M. Krieger, ’52 Global Health: Making a Difference Jennifer Litchman 10 Philip Mackowiak, ’70 The term “global health” hadn’t yet been coined in the Michael K. McEvoy, ’83 early 1970s when Maryland opened a clinical research Martin I. Passen, ’90 Gary D. Plotnick, ’66 center for vaccine initiatives in developing countries. Larry Pitrof A leader in global medical outreach, our faculty are Maurice N. Reid, ’99 now active in 23 developing countries across six Ernesto Rivera, ’66 continents. Jerome Ross, ’60 Luette S. Semmes, ’84 James Swyers The MAA Honor Roll of Donors 17 In this issue the Medical Alumni Association acknowl- Medical Alumni Association Board of Directors edges gifts it received between July 1, 2009 and June 30, 2010. Included are members of the John Beale Otha Myles, ’98 President Davidge Alliance, the school’s society for major donors. Tamara Burgunder, ’00 President-Elect Alumnus Profile: Robert Haddon, ’89 36 Nelson H. Goldberg, ’73 Vice President 10 A Giant Step for Medicine Victoria W. Smoot, ’80 As a child, Robert Haddon, ’89, was captivated by Treasurer America’s space exploration. He also had dreams of be- George M. -

89Th Annual Commencement North Carolina State University at Raleigh

89th Annual Commencement North Carolina State University at Raleigh Saturday, May 13 Nineteen Hundred and Seventy Eight Degrees Awarded 1977-78 CORRECTED COPY DEGREES CONFERRED :izii}?q. .. I,,c.. tA ‘mgi:E‘saé3222‘sSE\uT .t1 ac A corrected issue of undergraduate and graduate degrees including degrees awarded June 29, 1977, August 10, 1977, and December 21, 1977. Musical Program EXERCISES OF GRADUATION May 13, 1978 CARILLON CONCERT: 8:30 AM. The Memorial Tower Lucy Procter, Carillonneur COMMENCEMENT BAND CONCERT: 8:45 AM. William Neal Reynolds Coliseum AMPARITO ROCA Texidor EGMONT, Overture Beethoven PROCESSION OF THE NOBLES Rimsky—Korsakov AMERICA THE BEAUTIFUL Ward-Dragon PROCESSIONAL: 9:15 AM. March Processional Grundman RECESSIONAL: University Grand March Goldman NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIVERSITY COMMENCEMENT BAND Donald B. Adcock, Conductor The Alma Mater H’nrric In [Mimic In: ‘\I VIN M. FUUNI‘AIN, 2% BONNIE F. NORRIS. JR, ’2% “litre [lit \\'ind\t)f1)i.\ic50f[l}'blow o'cr [lIL' liicldx of Cdrolinc. lerc .NI.InLl\ chr Cherished N. C. State. .1\ [l1\' limmrcd Slirinc. So lift your \'()iCC\l Loudly sing From hill to occansidcl Our limrts cvcr hold you. N. C. State. in [he Folds of our love and pride. Exercises of Graduation William Neal Reynolds Coliseum Joab L. Thomas, Chancellor Presiding May 13, 1978 PROCESSIONAL, 9:15 AM. Donald B. Adcock Conductor, North Carolina State University CommencementBand theTheProcessional.Audience is requested to remain seated during INVOCATION The Reverend W. Joseph Mann Methodist Chaplain, North Carolina State University ADDRESS Roy H. Park President, Park Broadcasting Inc. and Park Newspapers, Inc. CONFERRING OF DEGREES .......................... -

War Crimes Act of 1995

WAR CRIMES ACT OF 1995 HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON IMMIGRATION AND CLAIMS OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON H.R. 2587 WAR CRIMES ACT OF 1995 JUNE 12, 1996 Serial No. 81 Legislative Office MAIN LIBRARY U.S. Dept. of Justice Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 27-100 CC WASHINGTON : 1996 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402 ISBN 0-16-053593-X COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois, Chairman CARLOS J. MOORHEAD, California JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., PATRICIA SCHROEDER, Colorado Wisconsin BARNEY FRANK, Massachusetts BILL McCOLLUM, Florida CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York GEORGE W. GEKAS, Pennsylvania HOWARD L. BERMAN, California HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina RICK BOUCHER, Virginia LAMAR SMITH, Texas JOHN BRYANT, Texas STEVEN SCHIFF, New Mexico JACK REED, Rhode Island ELTON GALLEGLY, California JERROLD NADLER, New York CHARLES T. CANADY, Florida ROBERT C. SCOTT, Virginia BOB INGLIS, South Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia XAVIER BECERRA, California STEPHEN E. BUYER, Indiana ZOE LOFGREN, California MARTIN R. HOKE, Ohio SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas SONNY BONO, California MAXINE WATERS, California FRED HEINEMAN, North Carolina ED BRYANT, Tennessee STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MICHAEL PATRICK FLANAGAN, Illinois BOB BARR, Georgia ALAN F. COFFEY, JR., General Counsel /Staff Director JULIAN EPSTEIN, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON IMMIGRATION AND CLAIMS LAMAR SMITH, Texas, Chairman ELTON GALLEGLY, California JOHN BRYANT, Texas CARLOS J. MOORHEAD, California BARNEY FRANK, Massachusetts BILL McCOLLUM, Florida CHARLES E. -

Extensions of Remarks E1239 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

July 11, 1996 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E1239 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS TRIBUTE TO BILL EMERSON For the women of Ledford it was their sec- unequalled. Over the years, he served as ond consecutive championship and their third clerk of works for every major municipal con- SPEECH OF in the past 6 years. With the title win, the Pan- struction project in the town of Provincetown. HON. MICHAEL BILIRAKIS thers capped off an outstanding 25±4 season And his inspection work has significantly re- under head coach John Ralls. duced the number of fires in the community. OF FLORIDA Like much of their season, the Panthers' In all his years of public service, Bill was on IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES pitching was the key to victory. The champion- call every day, literally 24 hours a day. Wheth- Tuesday, June 25, 1996 ship game's Most Valuable Player, Melissa er at home or at the office, the radio scanner Mr. BILIRAKIS. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to Petty, was superb on the mound, holding would always be on in the event of a fire, say goodbye to a friend. Although many Mem- Forbush to just one run off of five hits. But, flood, hurricane, or other emergency. bers of this body have risen and recounted Mr. Speaker, defense alone does not win Former town manager Bill McNulty said in a what kind of man, legislator, and public serv- championships. The Panther offense was led recent newspaper story ``there is no way they ant Bill Emerson was, I believe it certainly by Stacey Hinkle, who knocked two home will replace Bill. -

MICROCOMP Output File

FINAL EDITION OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS . OCTOBER 4, 1996 Compiled by ROBIN H. CARLE, Clerk of the House of Representatives http://clerk.house.gov Republicans in roman (236); Democrats in italic (196); Independent in SMALL CAPS (1); vacancies (2) 2d AR, 2d TX; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member’s district. ALABAMA 1 Sonny Callahan ........................................... Mobile 2 Terry Everett ............................................... Enterprise 3 Glen Browder .............................................. Jacksonville 4 Tom Bevill ................................................... Jasper 5 Robert E. (Bud) Cramer, Jr. ........................ Huntsville 6 Spencer Bachus ........................................... Vestavia Hills 7 Earl F. Hilliard ........................................... Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young ................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Matt Salmon ................................................ Mesa 2 Ed Pastor ..................................................... Phoenix 3 Bob Stump ................................................... Tolleson 4 John B. Shadegg .......................................... Phoenix 5 Jim Kolbe ..................................................... Tucson 6 J. D. Hayworth ............................................ Scottsdale ARKANSAS 1 Blanche Lambert Lincoln ........................... Helena 2 ——— ——— 1 -

Union Calendar No. 320 104Th Congress, 2Nd Session –––––––––– House Report 104–641

1 Union Calendar No. 320 104th Congress, 2nd Session ±±±±±±±±±± House Report 104±641 FRAUD AND ABUSE IN MEDICARE AND MEDICAID: STRONGER ENFORCEMENT AND BETTER MANAGEMENT COULD SAVE BILLIONS EIGHTH REPORT BY THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT together with ADDITIONAL VIEWS JUNE 27, 1996.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 25±491 CC WASHINGTON : 1996 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT WILLIAM F. CLINGER, JR., Pennsylvania, Chairman BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, New York CARDISS COLLINS, Illinois DAN BURTON, Indiana HENRY A. WAXMAN, California J. DENNIS HASTERT, Illinois TOM LANTOS, California CONSTANCE A. MORELLA, Maryland ROBERT E. WISE, JR., West Virginia CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut MAJOR R. OWENS, New York STEVEN SCHIFF, New Mexico EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida JOHN M. SPRATT, JR., South Carolina WILLIAM H. ZELIFF, JR., New Hampshire LOUISE MCINTOSH SLAUGHTER, New JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York York STEPHEN HORN, California PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania JOHN L. MICA, Florida GARY A. CONDIT, California PETER BLUTE, Massachusetts COLLIN C. PETERSON, Minnesota THOMAS M. DAVIS, Virginia KAREN L. THURMAN, Florida DAVID M. MCINTOSH, Indiana CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York JON D. FOX, Pennsylvania THOMAS M. BARRETT, Wisconsin RANDY TATE, Washington BARBARA-ROSE COLLINS, Michigan DICK CHRYSLER, Michigan ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of GIL GUTKNECHT, Minnesota Columbia MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana JAMES P. MORAN, Virginia WILLIAM J. MARTINI, New Jersey GENE GREEN, Texas JOE SCARBOROUGH, Florida CARRIE P. MEEK, Florida JOHN B. SHADEGG, Arizona CHAKA FATTAH, Pennsylvania MICHAEL PATRICK FLANAGAN, Illinois BILL BREWSTER, Oklahoma CHARLES F. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 141 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, MAY 1, 1995 No. 70 House of Representatives The House met at 12:30 p.m. and was instructions about what it is that the tax dollars in the way we spend them. called to order by the Speaker pro tem- people that we work for would like us But there was also growing interest in pore [Mrs. WALDHOLTZ]. to try and achieve as we go forward tackling the challenge of reforming our f with the congressional agenda. tax system in a comprehensive way, This year's spring break tragically, and I suspect that may have had some- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO as we all know, was overshadowed by thing to do with the fact that people TEMPORE the terrible bomb blast that occurred were trying to understand those very The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- April 19 in Oklahoma City. Our hearts difficult instruction forms at the last fore the House the following commu- and our prayers go out to the victims, minute on April 15 when they were nication from the Speaker: their families, the entire Oklahoma rushing to get in even before the ex- WASHINGTON, DC, community, and all the extraordinary tended deadline of April 17 this year. I May 1, 1995. Americans who have rallied together in think most people recognize that our I hereby designate the Honorable ENID G. this time of crisis. So many people current tax structure is inefficient, it WALDHOLTZ to act as Speaker pro tempore on were touched by this tragedy.