War Crimes Act of 1995

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Union Calendar No. 481 104Th Congress, 2D Session – – – – – – – – – – – – House Report 104–879

1 Union Calendar No. 481 104th Congress, 2d Session ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± House Report 104±879 REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES DURING THE ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS PURSUANT TO CLAUSE 1(d) RULE XI OF THE RULES OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES JANUARY 2, 1997.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 36±501 WASHINGTON : 1997 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois, Chairman 1 CARLOS J. MOORHEAD, California JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., PATRICIA SCHROEDER, Colorado Wisconsin BARNEY FRANK, Massachusetts BILL MCCOLLUM, Florida CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York GEORGE W. GEKAS, Pennsylvania HOWARD L. BERMAN, California HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina RICH BOUCHER, Virginia LAMAR SMITH, Texas JOHN BRYANT, Texas STEVEN SCHIFF, New Mexico JACK REED, Rhode Island ELTON GALLEGLY, California JERROLD NADLER, New York CHARLES T. CANADY, Florida ROBERT C. SCOTT, Virginia BOB INGLIS, South Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia XAVIER BECERRA, California STEPHEN E. BUYER, Indiana JOSEÂ E. SERRANO, New York 2 MARTIN R. HOKE, Ohio ZOE LOFGREN, California SONNY BONO, California SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas FRED HEINEMAN, North Carolina MAXINE WATERS, California 3 ED BRYANT, Tennessee STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MICHAEL PATRICK FLANAGAN, Illinois BOB BARR, Georgia ALAN F. COFFEY, JR., General Counsel/Staff Director JULIAN EPSTEIN, Minority Staff Director 1 Henry J. Hyde, Illinois, elected to the Committee as Chairman pursuant to House Resolution 11, approved by the House January 5 (legislative day of January 4), 1995. -

The Ethics of Interrogation and the Rule of Law Release Date: April 23, 2018

Release Date: April 23, 2018 CERL Report on The Ethics of Interrogation and the Rule of Law Release Date: April 23, 2018 CERL Report on The Ethics of Interrogation and the Rule of Law I. Introduction On January 25, 2017, President Trump repeated his belief that torture works1 and reaffirmed his commitment to restore the use of harsh interrogation of detainees in American custody.2 That same day, CBS News released a draft Trump administration executive order that would order the Intelligence Community (IC) and Department of Defense (DoD) to review the legality of torture and potentially revise the Army Field Manual to allow harsh interrogations.3 On March 13, 2018, the President nominated Mike Pompeo to replace Rex Tillerson as Secretary of State, and Gina Haspel to replace Mr. Pompeo as Director of the CIA. Mr. Pompeo has made public statements in support of torture, most notably in response to the Senate Intelligence Committee’s 2014 report on the CIA’s use of torture on post-9/11 detainees,4 though his position appears to have altered somewhat by the time of his confirmation hearing for Director of the CIA, and Ms. Haspel’s history at black site Cat’s Eye in Thailand is controversial, particularly regarding her oversight of the torture of Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri5 as well as her role in the destruction of video tapes documenting the CIA’s use of enhanced interrogation techniques.6 In light of these actions, President Trump appears to be signaling his support for legalizing the Bush-era techniques applied to detainees arrested and interrogated during the war on terror. -

Union Calendar No. 464 104Th Congress, 2Nd Session –––––––––– House Report 104–857

1 Union Calendar No. 464 104th Congress, 2nd Session ±±±±±±±±±± House Report 104±857 YEAR 2000 COMPUTER SOFTWARE CONVER- SION: SUMMARY OF OVERSIGHT FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS SIXTEENTH REPORT BY THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT SEPTEMBER 27, 1996.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 27±317 CC WASHINGTON : 1996 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT WILLIAM F. CLINGER, JR., Pennsylvania, Chairman BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, New York CARDISS COLLINS, Illinois DAN BURTON, Indiana HENRY A. WAXMAN, California J. DENNIS HASTERT, Illinois TOM LANTOS, California CONSTANCE A. MORELLA, Maryland ROBERT E. WISE, JR., West Virginia CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut MAJOR R. OWENS, New York STEVEN SCHIFF, New Mexico EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida JOHN M. SPRATT, JR., South Carolina WILLIAM H. ZELIFF, JR., New Hampshire LOUISE MCINTOSH SLAUGHTER, New JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York York STEPHEN HORN, California PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania JOHN L. MICA, Florida GARY A. CONDIT, California PETER BLUTE, Massachusetts COLLIN C. PETERSON, Minnesota THOMAS M. DAVIS, Virginia KAREN L. THURMAN, Florida DAVID M. MCINTOSH, Indiana CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York RANDY TATE, Washington THOMAS M. BARRETT, Wisconsin DICK CHRYSLER, Michigan BARBARA-ROSE COLLINS, Michigan GIL GUTKNECHT, Minnesota ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana Columbia WILLIAM J. MARTINI, New Jersey JAMES P. MORAN, Virginia JOE SCARBOROUGH, Florida GENE GREEN, Texas JOHN B. SHADEGG, Arizona CARRIE P. MEEK, Florida MICHAEL PATRICK FLANAGAN, Illinois CHAKA FATTAH, Pennsylvania CHARLES F. BASS, New Hampshire BILL BREWSTER, Oklahoma STEVEN C. LATOURETTE, Ohio TIM HOLDEN, Pennsylvania MARSHALL ``MARK'' SANFORD, South ELIJAH CUMMINGS, Maryland Carolina ÐÐÐ ROBERT L. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 104 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 141 WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, APRIL 7, 1995 No. 65 House of Representatives The House met at 11 a.m. and was PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE DESIGNATING THE HONORABLE called to order by the Speaker pro tem- The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the FRANK WOLF AS SPEAKER PRO pore [Mr. BURTON of Indiana]. TEMPORE TO SIGN ENROLLED gentleman from New York [Mr. SOLO- BILLS AND JOINT RESOLUTIONS f MON] come forward and lead the House in the Pledge of Allegiance. THROUGH MAY 1, 1995 DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO Mr. SOLOMON led the Pledge of Alle- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- TEMPORE giance as follows: fore the House the following commu- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the nication from the Speaker of the House fore the House the following commu- United States of America, and to the Repub- of Representatives: nication from the Speaker. lic for which it stands, one nation under God, WASHINGTON, DC, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. April 7, 1995. WASHINGTON, DC, I hereby designate the Honorable FRANK R. April 7, 1995. f WOLF to act as Speaker pro tempore to sign I hereby designate the Honorable DAN BUR- enrolled bills and joint resolutions through TON to act as Speaker pro tempore on this MESSAGE FROM THE SENATE May 1, 1995. day. NEWT GINGRICH, NEWT GINGRICH, A message from the Senate by Mr. Speaker of the House of Representatives. -

View Entire Issue in Pdf Format

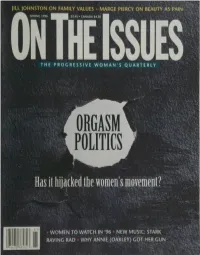

JILL JOHNSTON ON FAMILY VALUES MARGE PIERCY ON BEAUTY AS PAIN SPRING 1996 $3,95 • CANADA $4.50 THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY POLITICS Has it hijackedthe women's movement? WOMEN TO WATCH IN '96 NEW MUSIC: STARK RAVING RAD WHY ANNIE (OAKLEY) GOT HER GUN 7UU70 78532 The Word 9s Spreading... Qcaj filewsfrom a Women's Perspective Women's Jrom a Perspective Or Call /ibout getting yours At Home (516) 696-99O9 SPRING 1996 VOLUME V • NUMBER TWO ON IKE ISSUES THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY features 18 COVER STORY How Orgasm Politics Has Hi j acked the Women's Movement SHEILAJEFFREYS Why has the Big O seduced so many feminists—even Ms.—into a counterrevolution from within? 22 ELECTION'96 Running Scared KAY MILLS PAGE 26 In these anxious times, will women make a difference? Only if they're on the ballot. "Let the girls up front!" 26 POP CULTURE Where Feminism Rocks MARGARET R. SARACO From riot grrrls to Rasta reggae, political music in the '90s is raw and real. 30 SELF-DEFENSE Why Annie Got Her Gun CAROLYN GAGE Annie Oakley trusted bullets more than ballots. She knew what would stop another "he-wolf." 32 PROFILE The Hot Politics of Italy's Ice Maiden PEGGY SIMPSON At 32, Irene Pivetti is the youngest speaker of the Italian Parliament hi history. PAGE 32 36 ACTIVISM Diary of a Rape-Crisis Counselor KATHERINE EBAN FINKELSTEIN Italy's "femi Newtie" Volunteer work challenged her boundaries...and her love life. 40 PORTFOLIO Not Just Another Man on a Horse ARLENE RAVEN Personal twists on public art. -

Congress of the 33Mteb H>Tates( Ehhiil"

WILLIAM F. CLINGER, PENNSYLVANIA CARDISS COLLINS, ILLINOIS CHAIRMAN RANKING MINORITY MEMBER BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, NEW YORK , „ ' , HENRYA. WAXMAN,CALIFORNIA DAN INDIANA ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS tomlantos, J. DENNIS HASTERT, ILLINOIS ROBERT E. WISE, WEST VIRGINIA CONSTANCE A. MORELLA, MARYLAND CHRISTOPHER SHAYS,CONNECTICUT STEVEN SCHIFF, NEW MEXICO Congress ■* H>tates( EHHiiL". of the york 33mteb Louise Mcintosh slaughter,new ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, FLORIDA WILLIAM H. ZELIFF, JR., NEW HAMPSHIRE ** __, PAUL E.KANJORSKI, PENNSYLVANIA JOHN M. McHUGH,NEW YORK STEPHEN HORN,CALIFORNIA $ou*e of »epre*entattbe* COLLIN C.PETERSON, MINNESOTA JOHNL. MICA, FLORIDA KARENL. THURMAN,FLORIDA PETER BLUTE, MASSACHUSETTS THOMAS M. DAVIS, VIRGINIA COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT DAVID M. McINTOSH, INDIANA BARBARA-ROSE COLLINS, MICHIGAN JON D. FOX, PENNSYLVANIA 2157 Rayburn House Building 1 dc RANDYTATE,WASHINGTON Office S^SSNSSS DICK CHRYSLER, MICHIGAN GENE GREEN, TEXAS p GIL GUTKNECHT, MINNESOTA Washington, DC 20515-6143 CARRIE MEEK> Florida MARK E. SOUDER, INDIANA CHAKA FATTAH,PENNSYLVANIA WILLIAM J. MARTINI,NEW JERSEY BILLK. BREWSTER, OKLAHOMA JOE SCARBOROUGH,FLORIDA TIM HOLDEN,PENNSYLVANIA JOHNSHADEGG,ARIZONA MICHAEL PATRICK FLANAGAN, ILLINOIS CHARLES F. BASS, NEW HAMPSHIRE STEVE C. OHIO BERNARDSANDERS, VERMONT MARSHALL "MARK" SANFORD, SOUTH CAROLINA INDEPENDENT ROBERT L. EHRLICH, JR., MARYLAND MAJORITY—<2O2) 225-5074 September 13, 1996 MINORITY—(2O2) 225-5051 Dr. Edward Feigenbaum Chief Scientist U.S. Air Force Dear Dr. Feigenbaum: On behalf of the Committee on Government Reform and Oversight and the U.S. General Accounting Office, we want to thank you for your excellent keynote address during our September 5, 1996 symposium on "Exploring Expert Systems Technology: A Congressional Symposium on Technology and Productivity in Government." Your remarks set the stage for making the symposium a success. -

The International Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court • an international court set up to prosecute major human rights crimes • Jurisdiction over genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and aggression. • Proceedings may be initiated by (1) state party request, (2) the prosecutor, or (3) UN Security Council resolution. • In (1) and (2), the ICC’s jurisdiction is limited to citizens of member states and individuals accused of committing crimes on the territory of member states. In (3), these limits do not apply. • Principle of Complementarity. The Court acts only if the state of primary juris- diction proves itself “unwilling or unable” to launch criminal proceedings (art. 17). Situations under official investigation by the ICC: Uganda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan (Darfur), Central African Republic (2), Kenya, Libya, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Georgia, Burundi. Preliminary Examinations: Afghanistan, Myanmar/Bangladesh (Rohingya crisis), Colombia, Guinea, Iraq (UK), Nigeria, Palestine, Philippines, Ukraine, Venezuela. Convicted by the ICC: Thomas Lubanga (Dem. Rep. of Congo), Germain Katanga (Dem. Rep. of Congo), Bosco Ntaganda (DR Congo), Ahmad Al- Faqi Al-Mahdi (Mali), and a few others for obstruction of justice. Some individuals convicted at trial have been acquitted on appeal. On trial at the ICC: Abdallah Banda Abakaer Nourain (Sudan), Dominic Ongwen (Uganda). Wanted for trial at the ICC: Omar al-Bashir (Sudan), Seif al-Islam Gaddafi (Libya), Joseph Kony (Uganda), and several others Laurent Gbagbo, former president of Côte d’Ivoire • In late 2017, the prosecutor requested permission to open a formal investigation into crimes committed in Afghanistan. The investigation would cover crimes by the Afghan government, the Taliban, and US authorities. -

Fall 2010 • Volume 95 • Number 2

University of Maryland Fall 2010 • Volume 95 • Number 2 aking a D M if fe r e n c GLOBAL e HEALTH Bulletin Editorial Board Joseph S. McLaughlin, ’56 Chairman MedicineBulletin Roy Bands, ’84 University of Maryland Medical Alumni Association & School of Medicine Frank M. Calia, MD, MACP Nelson H. Goldberg, ’73 Donna S. Hanes, ’92 Joseph M. Herman, ’00 features Harry C. Knipp, ’76 Morton D. Kramer, ’55 Morton M. Krieger, ’52 Global Health: Making a Difference Jennifer Litchman 10 Philip Mackowiak, ’70 The term “global health” hadn’t yet been coined in the Michael K. McEvoy, ’83 early 1970s when Maryland opened a clinical research Martin I. Passen, ’90 Gary D. Plotnick, ’66 center for vaccine initiatives in developing countries. Larry Pitrof A leader in global medical outreach, our faculty are Maurice N. Reid, ’99 now active in 23 developing countries across six Ernesto Rivera, ’66 continents. Jerome Ross, ’60 Luette S. Semmes, ’84 James Swyers The MAA Honor Roll of Donors 17 In this issue the Medical Alumni Association acknowl- Medical Alumni Association Board of Directors edges gifts it received between July 1, 2009 and June 30, 2010. Included are members of the John Beale Otha Myles, ’98 President Davidge Alliance, the school’s society for major donors. Tamara Burgunder, ’00 President-Elect Alumnus Profile: Robert Haddon, ’89 36 Nelson H. Goldberg, ’73 Vice President 10 A Giant Step for Medicine Victoria W. Smoot, ’80 As a child, Robert Haddon, ’89, was captivated by Treasurer America’s space exploration. He also had dreams of be- George M. -

89Th Annual Commencement North Carolina State University at Raleigh

89th Annual Commencement North Carolina State University at Raleigh Saturday, May 13 Nineteen Hundred and Seventy Eight Degrees Awarded 1977-78 CORRECTED COPY DEGREES CONFERRED :izii}?q. .. I,,c.. tA ‘mgi:E‘saé3222‘sSE\uT .t1 ac A corrected issue of undergraduate and graduate degrees including degrees awarded June 29, 1977, August 10, 1977, and December 21, 1977. Musical Program EXERCISES OF GRADUATION May 13, 1978 CARILLON CONCERT: 8:30 AM. The Memorial Tower Lucy Procter, Carillonneur COMMENCEMENT BAND CONCERT: 8:45 AM. William Neal Reynolds Coliseum AMPARITO ROCA Texidor EGMONT, Overture Beethoven PROCESSION OF THE NOBLES Rimsky—Korsakov AMERICA THE BEAUTIFUL Ward-Dragon PROCESSIONAL: 9:15 AM. March Processional Grundman RECESSIONAL: University Grand March Goldman NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIVERSITY COMMENCEMENT BAND Donald B. Adcock, Conductor The Alma Mater H’nrric In [Mimic In: ‘\I VIN M. FUUNI‘AIN, 2% BONNIE F. NORRIS. JR, ’2% “litre [lit \\'ind\t)f1)i.\ic50f[l}'blow o'cr [lIL' liicldx of Cdrolinc. lerc .NI.InLl\ chr Cherished N. C. State. .1\ [l1\' limmrcd Slirinc. So lift your \'()iCC\l Loudly sing From hill to occansidcl Our limrts cvcr hold you. N. C. State. in [he Folds of our love and pride. Exercises of Graduation William Neal Reynolds Coliseum Joab L. Thomas, Chancellor Presiding May 13, 1978 PROCESSIONAL, 9:15 AM. Donald B. Adcock Conductor, North Carolina State University CommencementBand theTheProcessional.Audience is requested to remain seated during INVOCATION The Reverend W. Joseph Mann Methodist Chaplain, North Carolina State University ADDRESS Roy H. Park President, Park Broadcasting Inc. and Park Newspapers, Inc. CONFERRING OF DEGREES .......................... -

Black Letter Abuse: the US Legal Response to Torture Since 9/11 James Ross* James Ross Is Legal and Policy Director at Human Rights Watch, New York

Volume 89 Number 867 September 2007 Black letter abuse: the US legal response to torture since 9/11 James Ross* James Ross is Legal and Policy Director at Human Rights Watch, New York. Abstract The use of torture by the US armed forces and the CIA was not limited to ‘‘a few bad apples’’ at Abu Ghraib but encompassed a broader range of practices, including rendition to third countries and secret ‘‘black sites’’, that the US administration deemed permissible under US and international law. This article explores the various legal avenues pursued by the administration to justify and maintain its coercive interrogation programme, and the response by Congress and the courts. Much of the public debate concerned defining and redefining torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment. While US laws defining torture have moved closer to international standards, they have also effectively shut out those seeking redress for mistreatment from bringing their cases before the courts and protect those responsible from prosecution. I. Introduction: revelations of torture Allegations of torture by US personnel in the ‘‘global war on terror’’ only gained notoriety after photographs from Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq were broadcast on US television in April 2004. Prior to the mass dissemination of these disturbing images, reports in the media and in the publications of human rights organizations of torture and other mistreatment generated little public attention and evidently rang few alarm bells in the Pentagon (Department of Defense). Words did not * Thanks to Nicolette Boehland of Human Rights Watch for her assistance in preparing this article. 561 J. -

Extensions of Remarks E1239 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

July 11, 1996 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E1239 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS TRIBUTE TO BILL EMERSON For the women of Ledford it was their sec- unequalled. Over the years, he served as ond consecutive championship and their third clerk of works for every major municipal con- SPEECH OF in the past 6 years. With the title win, the Pan- struction project in the town of Provincetown. HON. MICHAEL BILIRAKIS thers capped off an outstanding 25±4 season And his inspection work has significantly re- under head coach John Ralls. duced the number of fires in the community. OF FLORIDA Like much of their season, the Panthers' In all his years of public service, Bill was on IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES pitching was the key to victory. The champion- call every day, literally 24 hours a day. Wheth- Tuesday, June 25, 1996 ship game's Most Valuable Player, Melissa er at home or at the office, the radio scanner Mr. BILIRAKIS. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to Petty, was superb on the mound, holding would always be on in the event of a fire, say goodbye to a friend. Although many Mem- Forbush to just one run off of five hits. But, flood, hurricane, or other emergency. bers of this body have risen and recounted Mr. Speaker, defense alone does not win Former town manager Bill McNulty said in a what kind of man, legislator, and public serv- championships. The Panther offense was led recent newspaper story ``there is no way they ant Bill Emerson was, I believe it certainly by Stacey Hinkle, who knocked two home will replace Bill. -

Applicability of the Geneva Conventions to “Armed Conflict” in the War on Terror

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 30, Issue 3 2006 Article 4 Applicability of the Geneva Conventions to “Armed Conflict” in the War on Terror Miles P. Fischer∗ ∗ Copyright c 2006 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Applicability of the Geneva Conventions to “Armed Conflict” in the War on Terror Miles P. Fischer Abstract This Essay briefly reviews the application of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 (the “Con- ventions”) in the so-called war on terror since September 11, 2001 (“9/11”), highlighting a few current issues of particular interest; notably, the concept of “armed conflict,” the role of Common Article 3, the impact of the MC Act, screening by “competent tribunals,” and enforcement of the Conventions in courts martial and against Central Intelligence Agency (“CIA”) operatives. APPLICABILITY OF THE GENEVA CONVENTIONS TO "ARMED CONFLICT" IN THE WAR ON TERROR Miles P. Fischer* What a roller-coaster ride it has been! Human rights advo- cates emerged from a black hole of international lawlessness to the exhilaration of victory in the U.S. Supreme Court's Rasul v. Bush1 and Hamdan v. Rumsfeld2 decisions in June 2004 and June 2006, only to fall back to political reality upon the adoption of the Military Commissions Act of 2006' (the "MC Act") in Octo- ber, 2006. And the ride goes on. This Essay briefly reviews the application of the Geneva Conventions of 1949' (the "Conventions") in the so-called war on terror since September 11, 2001 ("9/11"), highlighting a few current issues of particular interest; notably, the concept of "armed conflict," the role of Common Article 3,5 the impact of the MC Act, screening by "competent tribunals," and enforce- ment of the Conventions in courts martial and against Central Intelligence Agency ("CIA") operatives.