Handout Prayer in the Time of the Talmud

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dngd Zkqn Massekhet Hahammah

dngd zkqn Massekhet HaHammah Compiled and Translated with Commentary by Abe Friedman A Project of the Commission on Social Justice and Public Policy of the Leadership Council of Conservative Judaism Rabbi Leonard Gordon, Chair [email protected] Table of Contents Preface i Introduction v Massekhet HaHammah 1. One Who Sees the Sun 1 2. Creation of the Lights 5 3. Righteous and Wicked 9 4. Sun and Sovereignty 15 5. The Fields of Heaven 20 6. Star-Worshippers 28 7. Astrology and Omens 32 8. Heavenly Praise 41 9. Return and Redemption 45 Siyyum for Massekhet HaHammah 51 Bibliography 54 Preface Massekhet HaHammah was developed with the support of the Commission on Social Justice and Public Policy of the Conservative Movement in response to the “blessing of the sun” (Birkat HaHammah), a ritual that takes place every 28 years and that will fall this year on April 8, 2009 / 14 Nisan 5769, the date of the Fast of the Firstborn on the eve of Passover. A collection of halakhic and aggadic texts, classic and contemporary, dealing with the sun, Massekhet HaHammah was prepared as a companion to the ritual for Birkat HaHammah. Our hope is that rabbis and communities will study this text in advance of the Fast and use it both for adult learning about this fascinating ritual and as the text around which to build a siyyum, a celebratory meal marking the conclusion of a block of text study and releasing firstborn in the community from the obligation to fast on the eve of the Passover seder.1 We are also struck this year by the renewed importance of our focus on the sun given the universal concern with global warming and the need for non-carbon-based renewable resources, like solar energy. -

OF 17Th 2004 Gender Relationships in Marriage and Out.Pdf (1.542Mb)

Gender Relationships In Marriage and Out Edited by Rivkah Blau Robert S. Hirt, Series Editor THE MICHAEL SCHARF PUBLICATION TRUST of the YESHIVA UNIVERSITY PRESs New York OF 17 r18 CS2ME draft 8 balancediii iii 9/2/2007 11:28:13 AM THE ORTHODOX FORUM The Orthodox Forum, initially convened by Dr. Norman Lamm, Chancellor of Yeshiva University, meets each year to consider major issues of concern to the Jewish community. Forum participants from throughout the world, including academicians in both Jewish and secular fields, rabbis,rashei yeshivah, Jewish educators, and Jewish communal professionals, gather in conference as a think tank to discuss and critique each other’s original papers, examining different aspects of a central theme. The purpose of the Forum is to create and disseminate a new and vibrant Torah literature addressing the critical issues facing Jewry today. The Orthodox Forum gratefully acknowledges the support of the Joseph J. and Bertha K. Green Memorial Fund at the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary established by Morris L. Green, of blessed memory. The Orthodox Forum Series is a project of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, an affiliate of Yeshiva University OF 17 r18 CS2ME draft 8 balancedii ii 9/2/2007 11:28:13 AM Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Orthodox Forum (17th : 2004 : New York, NY) Gender relationships in marriage and out / edited by Rivkah Blau. p. cm. – (Orthodox Forum series) ISBN 978-0-88125-971-1 1. Marriage. 2. Marriage – Religious aspects – Judaism. 3. Marriage (Jewish law) 4. Man-woman relationships – Religious aspects – Judaism. I. -

The Torah As an Enactivist Model: Legal Thinking Beyond Natural Law and Positive Law

Ancilla Iuris Special Issue: Natural Law? Conceptions and Implications of Natural Law Elements of Religious Legal Discourse Prof. Dr. Ronen Reichman Dr. Britta Müller-Schauenburg (Guest Editors) Die Tora als enaktivistisches Muster: Rechtsdenken jenseits von Naturrecht und positivem Recht The Torah as an Enactivist Model: Legal thinking beyond natural law and positive law Asher J. Mattern* Translated by Jacob Watson Ancilla Iuris, 2017 Lagen des Rechts Synopsis E-ISSN 1661-8610 Constellations of Law DOAJ 1661-8610 ASHER J. MATTERN – THE TORAH AS AN ENACTIVIST MODEL Abstract Abstract Die abendländische, klassische wie moderne, Refle- The occidental reflexions on Law, classical as xion über das Recht wird durch den Gegensatz zwi- modern, is determined by the opposition between schen Naturrecht und positivem Recht bestimmt. natural and positive law. The Jewish understanding Das jüdische Verständnis des Gesetzes transzen- of Law transcends this dichotomy by projecting a diert diese Dichotomie durch die Projektion eines circular model: The divine Law is developped con- zirkulären Modells: Das göttliche Gesetz wird kon- cretely in the discussion of rabbinical scholars and kret in der Diskussion der rabbinischen Gelehrten this discussion has itself, as Oral Law, the status of entwickelt, und diese Diskussion hat selbst als being god-given. The Torah as the basis of the Jewish mündliches Gesetz den Status des gottgegebenen law is thus interpreted in the rabbinic tradition as Gesetzes. Die Tora als Grundlage des jüdischen the idea of a law in which the constructive interpre- Gesetzes wird also in der rabbinischen Tradition als tation is understood as a more precise discovery of die Idee eines Gesetzes interpretiert, in dem die kon- that what really is, that means an interpretation in struktive Interpretation als eine genauere Entde- which coincides with the invention and exploration ckung dessen, was wirklich ist, verstanden wird, d.h. -

Humor in Talmud and Midrash

Tue 14, 21, 28 Apr 2015 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Jewish Community Center of Northern Virginia Adult Learning Institute Jewish Humor Through the Sages Contents Introduction Warning Humor in Tanach Humor in Talmud and Midrash Desire for accuracy Humor in the phrasing The A-Fortiori argument Stories of the rabbis Not for ladies The Jewish Sherlock Holmes Checks and balances Trying to fault the Torah Fervor Dreams Lying How many infractions? Conclusion Introduction -Not general presentation on Jewish humor: Just humor in Tanach, Talmud, Midrash, and other ancient Jewish sources. -Far from exhaustive. -Tanach mentions “laughter” 50 times (root: tz-cho-q) [excluding Yitzhaq] -Talmud: Records teachings of more than 1,000 rabbis spanning 7 centuries (2nd BCE to 5th CE). Basis of all Jewish law. -Savoraim improved style in 6th-7th centuries CE. -Rabbis dream up hypothetical situations that are strange, farfetched, improbable, or even impossible. -To illustrate legal issues, entertain to make study less boring, and sharpen the mind with brainteasers. 1 -Going to extremes helps to understand difficult concepts. (E.g., Einstein's “thought experiments”.) -Some commentators say humor is not intentional: -Maybe sometimes, but one cannot avoid the feeling it is. -Reason for humor not always clear. -Rabbah (4th century CE) always began his lectures with a joke: Before he began his lecture to the scholars, [Rabbah] used to say something funny, and the scholars were cheered. After that, he sat in awe and began the lecture. [Shabbat 30b] -Laughing and entertaining are important. Talmud: -Rabbi Beroka Hoza'ah often went to the marketplace at Be Lapat, where [the prophet] Elijah often appeared to him. -

Du Bikour Holim À L'accompagnement Spirituel Rabbin

Du Bikour Holim à l’accompagnement spirituel Rabbin David Touboul et Rabbin Valerie Stessin 1. Talmud de Babylone, Nedarim 39b תלמוד בבלי, מסכת נדרים, דף לט עמוד ב Braïta : La visite aux malades n'a pas de limite. תניא: ביקור חולים אין לה שיעור. ?"(Que veut dire "pas de limite (ou mesure מאי אין לה שיעור? ,Rav Yossef a cru: pas de limite pour sa récompense mais Abayé lui a répondu : סבר רב יוסף למימר: אין שיעור למתן שכרה. ,et pour toutes les mitsvot אמר ליה אביי: וכל מצות מי יש שיעור למתן שכרן!? ?il y a-t-il une limite à leur récompense והא תנן: הוי זהיר במצוה קלה כבחמורה, : (Il est dit dans la Michna (Avot, 2,1 שאין אתה יודע מתן שכרן של מצות! (משנה אבות, ב' א') Fais attention aux mitsvot simples comme à celles qui sont graves, אלא אמר אביי: אפילו גדול אצל קטן. .car tu ne sais pas qu’elle est la récompense de chacune רבא אמר: אפילו מאה פעמים ביום. .Abayé dit : même un grand chez un petit אמר רבי אחא בר חנינא: .Rava dit: même cent fois par jour Rabbi Aha bar Hanina : כל המבקר חולה, נוטל אחד מששים בצערו. chaque personne qui rend visite à un malade, אמרי ליה: אם כן, ליעלון שיתין ולוקמוה! .(lui enlève un soixantième de sa douleur (peine אמר ליה: כעישורייתא דבי רבי, ובבן גילו. ,On lui a répondu : si c'est ainsi דתניא: רבי אומר: בת הניזונית מנכסי אחין, !que viennent soixante personnes et il sera guéri Il répondit: un soixantième d’après le dixième d’après נוטלת עישור נכסים. -

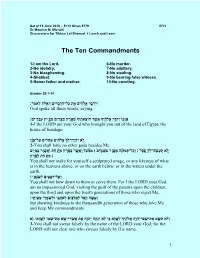

The Ten Commandments

Sat 8+15 June 2019 – 5+12 Sivan 5779 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Discussions for Tikkun Lel Shavuot + Lunch and Learn The Ten Commandments 1-I am the Lord. 6-No murder. 2-No idolatry. 7-No adultery. 3-No blaspheming. 8-No stealing. 4-Shabbat. 9-No bearing false witness. 5-Honor father and mother. 10-No coveting. Exodus 20:1-14 וַיְדַבֵֵּ֣ר אֱֹלה ִ֔ ים תאֵֵ֛ כָּל־הַדְ בָּר ִ֥ יםהָּאֵֵ֖ לֶּה לֵאמ ֹֽ ר׃ God spoke all these words, saying: אָֹּֽנכֵ֖י֙יְהוֵָּּ֣האֱֹלהֶּ ִ֔ יָךאֲשֶֶּׁ֧ רהֹוצֵ את ֵ֛ יָך ץ מֵאִֶּ֥רֶּ מ צְרֵַ֖ ים מבֵֵּ֣ ִֵּ֥֥֣ית עֲבָּד ֵֹּֽ֥֣ים׃ 1-I the LORD am your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt, the house of bondage: ֵּ֣ ֹֽל א י ְה ֶֹּֽיה־ ְל ֵ֛ ָָ֛֩ך ֱאֹל ִִ֥֥֨הים ֲא ֵ חִֵ֖֖֜רים ַעל־ ָּפ ָָֹּֽֽ֗נ ַי 2-You shall have no other gods besides Me. ֵּ֣ ֹֽל א ֹֽ ַת ֲע ִ֥֨ ֶּשה־ ְל ִָ֥ךֵּ֣ ֵֶּּ֣֙פ ֶּס ֙ל ׀ ְו ָּכל־ ְתמ ּו ִָּ֔נה ֲא ֶּ ֵּ֣שֵּ֥֣ר ַב ָּש ֵַּ֣֙מ י ֙ם ׀ מ ִַ֔מ ַעל ֹֽ ַו ֲא ִֶּ֥ש ָ֛֩ר ָּב ִֵָּ֥֖֨א ֶּרץ מִָּ֖֜ תֵַּ֥֣ ַחת וַאֲשִֶּ֥ ֵֵּּ֣֥֣רבַמֵַ֖ ֵֵּּ֣֥֣ים ׀מתִַ֥ ֵֵּּ֣֥֣חַת לָּאָָֹּֽֽ֗רֶּ ץ You shall not make for yourself a sculptured image, or any likeness of what is in the heavens above, or on the earth below, or in the waters under the earth. וְעַל־רבֵע ֵ֖ ים לְ ש נְאָּ ֵֹּֽ֥֣י׃ You shall not bow down to them or serve them. For I the LORD your God am an impassioned God, visiting the guilt of the parents upon the children, upon the third and upon the fourth generations of those who reject Me, וְעִ֥ שֶּה חֵֶּ֖֙סֶּד֙ לַאֲלָּפ יםִ֔ לְא הֲבֵַ֖י ּולְש מְרִֵ֥ י מצְ ו תָֹּֽ י׃ but showing kindness to the thousandth generation of those who love Me and keep My commandments. -

Leader's Guide.Final

ÁÅÒÉt Ï√u ‰@êbʼn “The real question is not why do we keep Passover but how do we continue to keep Passover year after year and keep it from becoming stultified! How can we be privileged to plan it so that, as Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook said, ‘The old may become new and the new may become holy.’” Leader’s Guide for IRA STEINGROOT A DIFFERENT NIGHT “One must make changes on By Noam Zion and David Dishon this night, so the children will notice and ask: ‘Why is this night different?’” MAIMONIDES “Only the lesson which is enjoyed can be learned well.” THE SHALOM HARTMAN INSTITUTE JUDAH HANASI JERUSALEM, ISRAEL Library of Congress Catalog 96-71600 American Friends of the Shalom Hartman Institute © Noam Zion and David Dishon 282 Grand Avenue, Suite 3, Englewood, NJ 07631 Published in the U.S.A. 1997 Fax: 201-894-0377 P.O. Box 8029, Jerusalem, Israel 93113 E-Mail: [email protected] 2CONTENTS a Table of Contents I.INTRODUCTIONS FOR THE II. SEDER SUPPLEMENTS LEADER OF THE SEDER Chapter 6 Chapter 1 The Four Questions in Depth: A Guide for the Perplexed: Ma Nishtana . 24 Clarifying the Roles • Maimonides: How to Activate Spontaneous Questions of the Leader of the Seder • Four Ideas to Stimulate Questioning by Noam Zion. 4 • In the Vernacular: Chapter 2 Ma Nishtana Translated in Many Languages The “Jazz” Haggadah . 8 • Interrogating a Famous Text: Questions and Answers about Ma Nishtana Chapter 3 • Quotations to Encourage a Questioning Mind Preparing for Seder Night: A Practical Manual . 9 Chapter 7 Chapter 4 Storytelling — Maggid . -

RABBINIC SLEEP ETHICS: JEWISH SLEEP CONDUCT in LATE ANTIQUITY1 Drew Kaplan

MillinHavivinEng06 7/19/06 11:07 AM Page 83 Drew Kaplan is a first-year student at Yeshi- vat Chovevei Torah. RABBINIC SLEEP ETHICS: JEWISH SLEEP CONDUCT IN LATE ANTIQUITY1 Drew Kaplan leeping occupies, on average, a third of a person’s life. The halakhic system, Sstriving as it does to regulate daily experiences, must therefore deal with sleep. While the Bible speaks of general categories of imperatives regarding sleep,2 these are not necessarily carried over into rabbinic categories of sleep ethics. Note that when discussing sleep ethics, I am not dealing with the morali- ty of sleeping, per se.3 My aim is to collect rabbinic prescriptions and proscrip- 1 My choice of the plural is deliberate—I wish to point to the multiple perspectives among the sages regarding the approach towards sleep. Given that the sages span several centuries and the lack of uniformity among them about sleep, “we should not expect to find in the literature of Rabbinic Judaism one single all-encompassing, comprehensive, systematic scheme in these matters. After all, ‘the Rabbis’ consisted of very many individ- ual personages whose lives spanned hundreds of years and who lived in two greatly dis- parate geographical areas, Israel and Babylon.” (Chaim Milikowsky, “Trajectories of Return, Restoration and Redemption in Rabbinic Judaism: Elijah, the Messiah, the War of Gog and the World To Come,” in Restoration: Old Testament, Jewish, and Christian Perspectives, ed. James M. Scott [Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2001], p. 265.) Nevertheless, there is somewhat of a historical canonization of earlier statements which get adopted over time in terms of developing a uniform sleep ethic. -

Mishkan, Mo'eid, and Synagogue: a Place of Encounter and Presence Parshat Vayakhel-Pekudei, Exodus 35:1-38:20/ 38:21-40:38| By

Mishkan, Mo’eid, and Synagogue: A Place of Encounter and Presence Parshat Vayakhel-Pekudei, Exodus 35:1-38:20/ 38:21-40:38| By Mark Greenspan “Synagogue Life” by Rabbi Craig T. Scheff, (pp.61-80) in The Observant Life Introduction The final chapters of Exodus contain an elaborate description of the building of the Tabernacle. Although many of these details of this project appear in earlier chapters the Torah goes on to describe the completion of the task as well as the various materials used in the implementation of the Tabernacle. In the final verses of Exodus we learn that the building of the Tabernacle was as momentous as the creation of the world. “When Moses had finished the work” (Exodus 40:33) echoes the language of creation: “On the seventh day God had finished the work that He had begun doing…” (Genesis 2:1). Once more we find the language of revelation in these final verses; the Tent of Meeting and the Tabernacle (Mishkan) are filled with a cloud just as Mount Sinai was surrounded by a cloud when God’s Presence descended on the mountain. The differences between the synagogue and the Tabernacle notwithstanding we are left to wonder about the connections between these two institutions. The Tabernacle was Israel’s first place of worship. The furnishings of our synagogue allow us to connect the synagogue with the Tabernacle: the ner tamid, the ark, and the menorah were among the furnishings of the ancient Mishkan. The Tabernacle was more than just a dwelling place of God; it was also a Tent of Meeting. -

Three Gifts for Yom Kippur to Our Hartman Rabbis from the Tales of the Talmudic Rabbis

Elul 5775-Tishrei 5776 Three Gifts for Yom Kippur to our Hartman Rabbis From the Tales of the Talmudic Rabbis Noam Zion SHALOM HARTMAN INSTITUTE JERUSALEM, ISRAEL Three Gifts for Yom Kippur to our Hartman Rabbis from the Tales of the Talmudic Rabbis Last summer after my work with the Hartman rabbinic program in Jerusalem, I met in Berlin with Professor Admiel Kosman, the academic director of the Liberal Seminar for Rabbis, the Abraham Geiger College. For years I have been an avid reader of his literary and spiritual essays on rabbinic tales such as Men's World, Reading Masculinity in Jewish Stories in a Spiritual Context. Deeply inspired by Martin Buber’s dialogical philosophy, he has brought out the subtle messages about inner piety and ethical relationships by reading between the lines of the quasi-biographic narratives in the Talmud. We hit on the idea of gathering three tales connected to Yom Kippur or other fasts of contrition and repentance and producing a kuntres, a compendium, of tales and their moral lessons for the edification of the rabbis in the field who seek to inspire the Jewish people every year for Yamim Noraim. With the help of my hevruta, Peretz Rodman, head of the Masorti Rabbinical Association in Israel, we edited and where necessary translated these tales and their interpretations. With the blessings and support of Lauren Berkun, director of the Hartman Rabbinic Leadership programs, we present you with these literary gifts with the hope that they will enrich your learning and spiritual lives as you go forth as the shlikhei tzibur to Am Yisrael for this Yom Kippur. -

An Introduction and Commentary on the Petichta to Esther Rabbah

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Religious Studies Honors Projects Religious Studies Department 2020 "To Bloom in Empty Space": An Introduction and Commentary on the Petichta to Esther Rabbah Ethan Nosanow Levin [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/reli_honors Part of the Jewish Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Levin, Ethan Nosanow, ""To Bloom in Empty Space": An Introduction and Commentary on the Petichta to Esther Rabbah" (2020). Religious Studies Honors Projects. 18. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/reli_honors/18 This Honors Project - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Religious Studies Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “TO BLOOM IN EMPTY SPACE”: AN INTRODUCTION AND COMMENTARY ON THE PETICHTA TO ESTHER RABBAH Ethan Levin Honors Project in Religious Studies Advisors: Nicholas J Schaser and Nanette Goldman Macalester College, Saint Paul, Minnesota 2 March 2020 1 Table of Contents Abstract ..................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 3 Introduction to the Petichta to Esther Rabbah ........................................................... -

Talmud Yerushalmi Kiddushin

YKIDDUSHIN Trattato yKiddushin Talmud di Gerusalemme a cura di Luciano Tagliacozzo le-zikron nefesh zio Aldo Terracina e zia Velia Tagliacozzo Terracina (la loro memoria sia di benedizione) ve lerefuà shelemà Ishti Myriam PAGINA 1 DI 138 W W W. E - B R E I. N E T YKIDDUSHIN Capitolo I - Mishnah Daf 1A Una donna viene sposata in tre modi, e torna padrona di se stessa in due modi. Viene sposata con denaro, con un documento e col coniugio. Con denaro: la Scuola di Shammay insegna con un DINARIUS o con qualcosa che vale un DINARIUS. La Scuola di Hillel opina, con una Perutà o qualcosa che valga una PERUTÀ. Quanto vale una Perutà? Un ottavo di un Asse italico. Ella torna a se stessa per divorzio o per morte del marito. Una cognata viene sposata per levirato col coniugio e torna a se stessa con lo scalzamento (HALITZA’) o la morte del cognato Ghemarà Dice la Mishnah: “Una donna viene sposata in tre modi con il denaro, con un documento o col coniugio” Insegna Rabbi Chyià che non solo attraverso la pratica di tutti e tre i modi, ma anche se ne pratica uno solo di essi. Per denaro da dove si ricava? E’ scritto (Deut. 24:1) “Quando abbia sposato un uomo sua moglie” Ma qui “abbia sposato” significa abbia acquisito con denaro. Per coniugio da dove si ricava? Perché è scritto: (Deut.24:1-2) “Quando un uomo abbia sposato una donna e abbia con lei convissuto” “e abbia con lei convissuto, indica l’avvenuta convivenza.