00A-Ariel 37(2-3)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Safe Spectacular

Voyager’s World | July 2018 | P1 Vol XV Issue X Pages 40 August 2018 Rs 60 SAFE &SPECTACULAR Voyager’s World @VoyagersWorld THE ONLY MULTI DESTINATION EVENT THE ONLY TRADE SHOW FOCUSSED ON OUTBOUND TRAVEL Southeast Asia 01st - 05th October 2018 Bangkok | Kuala Lumpur | Jakarta | Singapore (Optional) India Edition 1 8th - 15th January 2019 Delhi | Kolkata | Hyderabad | Ahmedabad | Mumbai Middle East 10th - 13th February 2019 Dubai | Kuwait | Qatar | Oman (Optional) India Edition 2 25th February 2019 - 1st March 2019 Mumbai | Bengaluru | Chandigarh | Delhi A B2B trade event connecting buyers & suppliers of outbound travel industry from across the globe, oering unparalleled networking & contracting oppertunities. • The Middle East Edition of OTR - 2018 witnessed a footfall of 550 eminent buyers across Dubai - Kuwait - Qatar - Oman. • Over 1800 buyers attended the India - Edition 1 of OTR in January, 2018 across Mumbai - Chennai - Bengaluru - Delhi. • India Edition 2 for 2018 held across Delhi - Ahmedabad - Mumbai witnessed an overwhelming presence of over 1200 buyers. • OTR is the only focused buyer event on invitation basis; & witnesses key decision makers amongst the travel trade For Participation Please Contact: Email: [email protected] | [email protected] Mob: +91 9945279001 | +91 9845238980 For Sponsorship Please Contact: Email: [email protected] Mob: +91 8748929534 www.outboundtravelroadshow.com THE ONLY MULTI DESTINATION EVENT THE ONLY TRADE SHOW FOCUSSED ON OUTBOUND TRAVEL Southeast Asia 01st - 05th October 2018 Bangkok | Kuala Lumpur | Jakarta | Singapore (Optional) India Edition 1 8th - 15th January 2019 Delhi | Kolkata | Hyderabad | Ahmedabad | Mumbai Middle East 10th - 13th February 2019 Dubai | Kuwait | Qatar | Oman (Optional) India Edition 2 25th February 2019 - 1st March 2019 Mumbai | Bengaluru | Chandigarh | Delhi A B2B trade event connecting buyers & suppliers of outbound travel industry from across the globe, oering unparalleled networking & contracting oppertunities. -

The Long Littoral Project: South China Sea a Maritime Perspective on Indo-Pacific Security

The Long Littoral Project: South China Sea A Maritime Perspective on Indo-Pacific Security Michael A. McDevitt • M. Taylor Fravel • Lewis M. Stern Cleared for Public Release IRP-2012-U-002321-Final March 2013 Strategic Studies is a division of CNA. This directorate conducts analyses of security policy, regional analyses, studies of political-military issues, and strategy and force assessments. CNA Strategic Studies is part of the global community of strategic studies institutes and in fact collaborates with many of them. On the ground experience is a hallmark of our regional work. Our specialists combine in-country experience, language skills, and the use of local primary-source data to produce empirically based work. All of our analysts have advanced degrees, and virtually all have lived and worked abroad. Similarly, our strategists and military/naval operations experts have either active duty experience or have served as field analysts with operating Navy and Marine Corps commands. They are skilled at anticipating the “problem after next” as well as determining measures of effectiveness to assess ongoing initiatives. A particular strength is bringing empirical methods to the evaluation of peace-time engagement and shaping activities. The Strategic Studies Division’s charter is global. In particular, our analysts have proven expertise in the following areas: The full range of Asian security issues The full range of Middle East related security issues, especially Iran and the Arabian Gulf Maritime strategy Insurgency and stabilization Future national security environment and forces European security issues, especially the Mediterranean littoral West Africa, especially the Gulf of Guinea Latin America The world’s most important navies Deterrence, arms control, missile defense and WMD proliferation The Strategic Studies Division is led by Dr. -

Winter 2020 Full Issue

Naval War College Review Volume 73 Number 1 Winter 2020 Article 1 2020 Winter 2020 Full Issue The U.S. Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Naval War College, The U.S. (2020) "Winter 2020 Full Issue," Naval War College Review: Vol. 73 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol73/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naval War College: Winter 2020 Full Issue Winter 2020 Volume 73, Number 1 Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2020 1 Naval War College Review, Vol. 73 [2020], No. 1, Art. 1 Cover Two modified Standard Missile 2 (SM-2) Block IV interceptors are launched from the guided-missile cruiser USS Lake Erie (CG 70) during a Missile Defense Agency (MDA) test to intercept a short-range ballistic-missile target, conducted on the Pacific Missile Range Facility, west of Hawaii, in 2008. The SM-2 forms part of the Aegis ballistic-missile defense (BMD) program. In “A Double-Edged Sword: Ballistic-Missile Defense and U.S. Alli- ances,” Robert C. Watts IV explores the impact of BMD on America’s relationship with NATO, Japan, and South Korea, finding that the forward-deployed BMD capability that the Navy’s Aegis destroyers provide has served as an important cement to these beneficial alliance relationships. -

Northumbria Research Link

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Baxter, Katherine and Smith, Lytton (2016) Writing in Translation: Robert Sullivan’s 'Star Waka' and Craig Santos Perez’s 'from unincorporated territory'. Literary Geographies, 2 (2). pp. 263-283. ISSN 2397-1797 Published by: Literary Geographies URL: http://www.literarygeographies.net/index.php/LitGe... <http://www.literarygeographies.net/index.php/LitGeogs/article/view/55> This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/28810/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published -

Jumlah Wilayah Kerja Statistik Provinsi Kabupaten Kota Kecamatan Desa

JUMLAH WILAYAH KERJA STATISTIK BLOK PROVINSI KABUPATEN KOTA KECAMATAN DESA SENSUS 11 ACEH 18 5 287 6.491 16.119 12 SUMATERA UTARA 25 8 422 5.876 40.291 13 SUMATERA BARAT 12 7 176 1.033 15.182 14 RIAU 10 2 157 1.736 18.949 15 JAMBI 9 2 131 1.484 11.404 16 SUMATERA SELATAN 11 4 225 3.205 26.433 17 BENGKULU 9 1 124 1.508 6.588 18 LAMPUNG 12 2 214 2.511 27.867 KEPULAUAN BANGKA 19 BELITUNG 6 1 46 380 4.093 21 KEPULAUAN RIAU 5 2 59 371 5.955 31 DKI JAKARTA 1 5 44 267 31.748 32 JAWA BARAT 17 9 626 5.941 147.158 33 JAWA TENGAH 29 6 573 8.578 116.534 34 D I YOGYAKARTA 4 1 78 438 12.016 35 JAWA TIMUR 29 9 662 8.505 146.183 36 BANTEN 4 4 154 1.545 31.182 51 BALI 8 1 57 716 11.793 52 NUSA TENGGARA BARAT 8 2 116 1.122 18.126 53 NUSA TENGGARA TIMUR 20 1 293 3.052 14.147 61 KALIMANTAN BARAT 12 2 176 1.970 14.666 62 KALIMANTAN TENGAH 13 1 132 1.528 11.475 63 KALIMANTAN SELATAN 11 2 151 2.000 14.300 64 KALIMANTAN TIMUR 10 4 146 1.469 15.111 71 SULAWESI UTARA 11 4 159 1.733 10.446 72 SULAWESI TENGAH 10 1 166 1.903 10.391 73 SULAWESI SELATAN 21 3 304 3.015 23.788 74 SULAWESI TENGGARA 10 2 205 2.159 8.979 75 GORONTALO 5 1 75 732 3.555 76 SULAWESI BARAT 5 0 69 645 3.842 81 MALUKU 9 2 90 1.027 4.850 82 MALUKU UTARA 7 2 112 1.075 4.022 91 PAPUA BARAT 10 1 175 1.441 4.441 94 PAPUA 28 1 389 3.619 11.370 JUMLAH 399 98 6.793 79.075 843. -

Ka Mate Ka Ora: a New Zealand Journal of Poetry and Poetics

ka mate ka ora: a new zealand journal of poetry and poetics Issue 4 September 2007 Poetry at Auckland University Press Elizabeth Caffin Weathers on this shore want sorts of words. (Kendrick Smithyman, ‘Site’) Auckland University Press might never have been a publisher of poetry were it not for Kendrick Smithyman. It was his decision. As Dennis McEldowney recalls, a letter from Smithyman on 31 March 1967 offering the manuscript of Flying to Palmerston, pointed out that ‘it is to the university presses the responsibility is falling for publishing poetry. Pigheaded and inclined to the parish pump, I would rather have it appear in New Zealand if it appears anywhere’.1 Dennis, who became Editor of University Publications in 1966 and in the next two decades created a small but perfectly formed university press, claimed he lacked confidence in judging poetry. But Kendrick and C. K. Stead, poets and academics both, became his advisors and he very quickly established an impressive list. At its core were the great New Zealand modernist poets. Dennis published five books by Smithyman, three by Stead and three by Curnow starting with the marvellous An Incorrigible Music in 1979.2 Curnow and Smithyman were not young and had published extensively elsewhere but most would agree that their greatest work was written in their later years; and AUP published it. Soon a further group of established poets was added: three books by Elizabeth Smither, one by Albert Wendt, one by Kevin Ireland. And then a new generation, the exuberant poets of the 1960s and 1970s such as Ian Wedde (four books), Bill Manhire, Bob Orr, Keri Hulme, Graham Lindsay, Michael Harlow. -

3B2 to Ps Tmp 1..74

2001R2501 — EN — 01.01.2002 — 000.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 2501/2001 of 10 December 2001 applying a scheme of generalised tariff preferences for the period from 1 January 2002 to 31 December 2004 (OJ L 346, 31.12.2001, p. 1) Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 137, 25.5.2002, p. 26 (2501/2001) 2001R2501 — EN — 01.01.2002 — 000.001 — 2 ▼B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 2501/2001 of 10 December 2001 applying a scheme of generalised tariff preferences for the period from 1 January 2002 to 31 December 2004 THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, and in particular Article 133 thereof, Having regard to the proposal from the Commission (1), Having regard to the opinion of the European Parliament (2), Having regard to the Opinion of the Economic and Social Committee (3), Whereas: (1) Since 1971, the Community has granted trade preferences to developing countries, in the framework of its scheme of general- ised tariff preferences. (2) The Community's common commercial policy must be consis- tent with and consolidate the objectives of development policy, in particular the eradication of poverty and the promotion of sustainable development in the developing countries. (3) A communication from the Commission to the Council of 1 June 1994 sets out the guidelines for the application of the scheme of generalised tariff preferences for the period 1995 to 2004. -

Indigenous Transnational Visibilities and Identities in Oceania Establishing Alternative Geographies Across Boundaries

Université de Montréal Indigenous Transnational Visibilities and Identities in Oceania Establishing Alternative Geographies across Boundaries Par Coline Souilhol Département de littératures et de langues du monde Arts et Sciences Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du grade de maîtrise en études anglaises Juin 2020 © Coline Souilhol, 2020 Université de Montréal Département de littératures et de langues du monde Faculté des arts et des sciences Ce mémoire intitulé Indigenous Transnational Visibilities and Identities in Oceania Establishing Alternative Geographies across Boundaries Présenté par Coline Souilhol A été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes Heather Meek Membre du jury Sarah Henzi Membre du jury Heike Harting Membre du jury 1 Résumé Pendant la deuxième moitié du vingtième siècle, les régions du Pacifique, et notamment l’Australie et la Nouvelle-Zélande, ont vu augmenter les mouvements de migrations. Ces derniers ont permis une diversification des concepts de nationalité, d’identité, de langage et d’espace. De ce fait, bon nombre d’auteurs ont donc décidé d’approcher leurs écrits à travers le spectre du transnationalisme et ont cherché à repousser les limites culturelles et les frontières géographiques -imposées par un état colonial.- Par conséquent, c’est avec une approche comparative que j’analyserai, en tenant ainsi compte de la constante évolution des nouveaux cadres géographiques et culturels, le recueil de poèmes Star Waka (1999) de l’auteur maori Robert Sullivan, le roman graphique Night Fisher (2005) de l’artiste hawaiien R. Kikuo Johnson et le roman Carpentaria de l’autrice waanyi Alexis Wright. En effet, j’examinerai la formation des identités autochtones en lien avec le lieu natal respectif de chaque auteur tout en tenant compte de l’évolution de la notion de frontière, qu’elle soit locale ou nationale. -

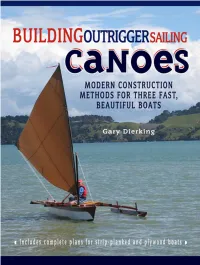

Building Outrigger Sailing Canoes

bUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES INTERNATIONAL MARINE / McGRAW-HILL Camden, Maine ✦ New York ✦ Chicago ✦ San Francisco ✦ Lisbon ✦ London ✦ Madrid Mexico City ✦ Milan ✦ New Delhi ✦ San Juan ✦ Seoul ✦ Singapore ✦ Sydney ✦ Toronto BUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES Modern Construction Methods for Three Fast, Beautiful Boats Gary Dierking Copyright © 2008 by International Marine All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-159456-6 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-148791-3. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw-Hill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the work, you may not decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon, transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent. -

A 1. Vbl. Par. 1St. Pers. Sg. Past & Present

A A 1. vbl. par. 1st. pers. sg. past & present - I - A peiki, I refuse, I won't, I can't. A ninayua kiweva vagagi. I am in two minds about a thing. A gisi waga si laya. I see the sails of the canoes. (The pronoun yaegu I, needs not to be expressed but for emphasis, being understood from the verbal particle.) 2. Abrev. of AMA. A-ma-tau-na? Which this man? 3. changes into E in dipthongues AI? EL? E. Paila, peila, pela. Wa valu- in village - We la valu - in his village. Ama toia, Ametoia, whence. Amenana, Which woman? Changes into I, sg. latu (son) pl. Litu -- vagi, to do, ku vigaki. Changes into O, i vitulaki - i vituloki wa- O . Changes into U, sg. tamala, father, - Pl. tumisia. sg. tabula gd.-father, pl. tubula. Ama what, amu, in amu ku toia? Where did you come from? N.B. several words beginning with A will be found among the KA 4. inverj. of disgust, disappointment. 5. Ambeisa wolaula? How Long? [see page 1, backside] ageva, or kageva small, fine shell disks. (beads in Motu) ago exclaims Alas! Agou! (pain, distress) agu Adj. poss. 1st. pers. sg. expressing near possession. See Grammar. Placed before the the thing possessed. Corresponds to gu, which is suffixed to the thing possessed. According to the classes of the nouns in Melanesian languages. See in the Grammar differences in Boyova. Memo: The other possess. are kagu for food, and ula for remove possession, both placed before the things possessed. Dabegu, my dress or dresses, - the ones I am wearing. -

Climate Change and Agriculture in the United States: Effects and Adaptation

Climate Change and Agriculture in the United States: Effects and Adaptation USDA Technical Bulletin 1935 Climate Change and Agriculture in the United States: Effects and Adaptation This document may be cited as: Walthall, C.L., J. Hatfield, P. Backlund, L. Lengnick, E. Marshall, M. Walsh, S. Adkins, M. Aillery, E.A. Ainsworth, C. Ammann, C.J. Anderson, I. Bartomeus, L.H. Baumgard, F. Booker, B. Bradley, D.M. Blumenthal, J. Bunce, K. Burkey, S.M. Dabney, J.A. Delgado, J. Dukes, A. Funk, K. Garrett, M. Glenn, D.A. Grantz, D. Goodrich, S. Hu, R.C. Izaurralde, R.A.C. Jones, S-H. Kim, A.D.B. Leaky, K. Lewers, T.L. Mader, A. McClung, J. Morgan, D.J. Muth, M. Nearing, D.M. Oosterhuis, D. Ort, C. Parmesan, W.T. Pettigrew, W. Polley, R. Rader, C. Rice, M. Rivington, E. Rosskopf, W.A. Salas, L.E. Sollenberger, R. Srygley, C. Stöckle, E.S. Takle, D. Timlin, J.W. White, R. Winfree, L. Wright-Morton, L.H. Ziska. 2012. Climate Change and Agriculture in the United States: Effects and Adaptation. USDA Technical Bulletin 1935. Washington, DC. 186 pages. This document was produced as part of of a collaboration between the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, and the National Center for Atmospheric Research under USDA cooperative agreement 58-0111-6-005. NCAR’s primary sponsor is the National Science Foundation. Images courtesy of USDA and UCAR. This report is available on the Web at: http://www.usda.gov/oce/climate_change/effects.htm Printed copies may be purchased from the National Technical Information Service. -

Looking for Truthiness

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research or private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the author. i Looking for Truthiness A personal investigation into bicultural poetry from the Bay of Islands presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Creative Writing at Massey University, Albany New Zealand. Shelley Marie Arlidge 2020 ii Abstract The creative component of this thesis mixes poems, prose poems and prose. Boundaries are blurred. English and Te Reo Māori intermingle and sit side by side, as do memoir and writing situated in the present. Time is sometimes curved and loved ones are brought back. Parts of the portfolio touch on environmental issues. The main recurring theme is a search, not only for ‘truthiness’ which may help the author find a comfortable place to stand, but also for physical, intellectual and emotional nourishment from food, nature, family, community and place. The critical component is an exegesis, which looks at influences on this writing, influences which are both local and international, male and female, Māori and Pākehā. A research question is explored in the exegesis – What are the social, historical and personal constraints and drivers behind the work presented and considered here? Particular attention is given to the consequences of colonisation in Aotearoa-New Zealand, with a focus on writing from the greater Bay of Islands area by Robert Sullivan and Glenn Colquhoun. Although three decades have passed since their first books were published, many of the issues their writing explored remain unresolved.