Ojionuka Arinze

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case #2 United States of America (Respondent)

Model International Court of Justice (MICJ) Case #2 United States of America (Respondent) Relocation of the United States Embassy to Jerusalem (Palestine v. United States of America) Arkansas Model United Nations (AMUN) November 20-21, 2020 Teeter 1 Historical Context For years, there has been a consistent struggle between the State of Israel and the State of Palestine led by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). In 2018, United States Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced that the U.S. embassy located in Tel Aviv would be moving to the city of Jerusalem.1 Palestine, angered by the embassy moving, filed a case with the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in 2018.2 The history of this case, U.S. relations with Israel and Palestine, current events, and why the ICJ should side with the United States will be covered in this research paper. Israel and Palestine have an interesting relationship between war and competition. In 1948, Israel captured the west side of Jerusalem, and the Palestinians captured the east side during the Arab-Israeli War. Israel declared its independence on May 14, 1948. In 1949, the Lausanne Conference took place, and the UN came to the decision for “corpus separatum” which split Jerusalem into a Jewish zone and an Arab zone.3 At this time, the State of Israel decided that Jerusalem was its “eternal capital.”4 “Corpus separatum,” is a Latin term meaning “a city or region which is given a special legal and political status different from its environment, but which falls short of being sovereign, or an independent city-state.”5 1 Office of the President, 82 Recognizing Jerusalem as the Capital of the State of Israel and Relocating the United States Embassy to Israel to Jerusalem § (2017). -

Arab-Israeli Relations

FACTSHEET Arab-Israeli Relations Sykes-Picot Partition Plan Settlements November 1917 June 1967 1993 - 2000 May 1916 November 1947 1967 - onwards Balfour 1967 War Oslo Accords which to supervise the Suez Canal; at the turn of The Balfour Declaration the 20th century, 80% of the Canal’s shipping be- Prepared by Anna Siodlak, Research Associate longed to the Empire. Britain also believed that they would gain a strategic foothold by establishing a The Balfour Declaration (2 November 1917) was strong Jewish community in Palestine. As occupier, a statement of support by the British Government, British forces could monitor security in Egypt and approved by the War Cabinet, for the establish- protect its colonial and economic interests. ment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. At the time, the region was part of Otto- Economics: Britain anticipated that by encouraging man Syria administered from Damascus. While the communities of European Jews (who were familiar Declaration stated that the civil and religious rights with capitalism and civil organisation) to immigrate of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine to Palestine, entrepreneurialism and development must not be deprived, it triggered a series of events would flourish, creating economic rewards for Brit- 2 that would result in the establishment of the State of ain. Israel forcing thousands of Palestinians to flee their Politics: Britain believed that the establishment of homes. a national home for the Jewish people would foster Who initiated the declaration? sentiments of prestige, respect and gratitude, in- crease its soft power, and reconfirm its place in the The Balfour Declaration was a letter from British post war international order.3 It was also hoped that Foreign Secretary Lord Arthur James Balfour on Russian-Jewish communities would become agents behalf of the British government to Lord Walter of British propaganda and persuade the tsarist gov- Rothschild, a prominent member of the Jewish ernment to support the Allies against Germany. -

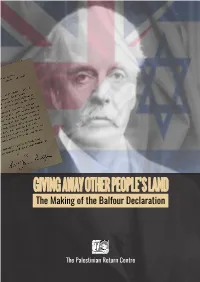

The Making of the Balfour Declaration

The Making of the Balfour Declaration The Palestinian Return Centre i The Palestinian Return Centre is an independent consultancy focusing on the historical, political and legal aspects of the Palestinian Refugees. The organization offers expert advice to various actors and agencies on the question of Palestinian Refugees within the context of the Nakba - the catastrophe following the forced displacement of Palestinians in 1948 - and serves as an information repository on other related aspects of the Palestine question and the Arab-Israeli conflict. It specializes in the research, analysis, and monitor of issues pertaining to the dispersed Palestinians and their internationally recognized legal right to return. Giving Away Other People’s Land: The Making of the Balfour Declaration Editors: Sameh Habeeb and Pietro Stefanini Research: Hannah Bowler Design and Layout: Omar Kachouch All rights reserved ISBN 978 1 901924 07 7 Copyright © Palestinian Return Centre 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publishers or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. مركز العودة الفلسطيني PALESTINIAN RETURN CENTRE 100H Crown House North Circular Road, London NW10 7PN United Kingdom t: 0044 (0) 2084530919 f: 0044 (0) 2084530994 e: [email protected],uk www.prc.org.uk ii Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 -

History and Politics of Nomadism in Modern Palestine (1882-1948)

History and Politics of Nomadism in Modern Palestine (1882-1948) A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Arabic and Islamic Studies By Seraje Assi, M.A. Washington, DC May 30, 2016 Copyright 2016 by Seraje Assi All Rights Reserved ii History and Politics of Nomadism in Modern Palestine (1882-1948) Seraje Assi, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Judith Tucker, Ph.D. ABSTRACT My research examines contending visions on nomadism in modern Palestine. It is a comparative study that covers British, Arab and Zionist attitudes to nomadism. By nomadism I refer to a form of territorialist discourse, one which views tribal formations as the antithesis of national and land rights, thus justifying the exteriority of nomadism to the state apparatus. Drawing on primary sources in Arabic and Hebrew, I show how local conceptions of nomadism have been reconstructed on new legal taxonomies rooted in modern European theories and praxis. By undertaking a comparative approach, I maintain that the introduction of these taxonomies transformed not only local Palestinian perceptions of nomadism, but perceptions that characterized early Zionist literature. The purpose of my research is not to provide a legal framework for nomadism on the basis of these taxonomies. Quite the contrary, it is to show how nomadism, as a set of official narratives on the Bedouin of Palestine, failed to imagine nationhood and statehood beyond the single apparatus of settlement. iii The research and writing of this thesis is dedicated to everyone who helped along the way. -

From Sykes-Picot to Present; the Centenary Aim of the Zionism on Syria and Iraq

From Sykes-Picot to Present; The Centenary Aim of The Zionism on Syria and Iraq Ergenekon SAVRUN1 Özet Ower the past hundred years, much of the Middle East was arranged by Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges Picot. During the World War I Allied Powers dominanced Syria by the treaty of Sykes-Picot which was made between England and France. After the Great War Allied Powers (England-France) occupied Syria, Palestine, Iraq or all Al Jazeera and made them mandate. As the Arab World and Syria in particular is in turmoil, it has become fashionable of late to hold the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement responsible for the current storm surge. On the other hand, Theodor Herzl, the father of political Zionism, published a star-eyed novel entitled Altneuland (Old-New Land) in 1902. Soon after The Britain has became the biggest supporter of the Jews, but The Britain had to occupy the Ottoman Empire’s lands first with some allies, and so did it. The Allied Powers defeated Germany and Ottoman Empire. Nevertheless, the gamble paid off in the short term for Britain and Jews. In May 14, 1948 Israel was established. Since that day Israel has expanded its borders. Today, new opportunity is Syria just standing infront of Israel. We think that Israel will fill the headless body gap with Syrian and Iraqis Kurds with the support of Western World. In this article, we will emerge and try to explain this idea. Anahtar Kelimeler: Sykes-Picot Agrement, Syria-Iraq Issue, Zionism, Isreal and Kurds’ Relation. Sykes-Picot’dan Günümüze; Suriye ve Irak Üzerinde Siyonizm’in Yüz Yıllık Hedefleri Abstract Geçtiğimiz son yüzyılda, Orta Doğu’nun birçok bölümü Sir Mark Sykes ve François Georges Picot tarafından tanzim edildi. -

Was the Balfour Declaration a Colonial Document? » Mosaic

11/2/2020 Was the Balfour Declaration a Colonial Document? » Mosaic WAS THE BALFOUR DECLARATION A COLONIAL DOCUMENT? https://mosaicmagazine.com/observation/israel-zionism/2020/10/was-the-balfour-declaration-a-colonial-document/ So goes the accusation. But the public commitment Britain made to the Jews in Palestine is very different from the Sykes- Picot accord and other secret “treaties” carving up native lands. October 28, 2020 | Martin Kramer About the author: Martin Kramer teaches Middle Eastern history and served as founding president at Shalem College in Jerusalem, and is the Koret distinguished fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. “His Majesty’s Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” This is the operative sentence in the Balfour Declaration, issued 103 years ago on November 2 by British Foreign Secretary Lord Arthur James Balfour on behalf of the British government, and transmitted by Balfour to Lord Walter Rothschild for passing along to the British Zionist Federation. In 2017, on the centenary of the declaration, the anti-Zionist Oxford historian Avi Shlaim described it, more than once, as “a classic colonial document.” No doubt many today are inclined to see it the same way. And indeed it does have some of the external trappings of a “classic colonial document,” addressed as it was by one lord (Balfour) to another (Rothschild) and delivered, one can easily imagine, by a white-gloved emissary from the Foreign Office to the Rothschild palace in an envelope to be presented to the recipient on Lord Allenby, Lord Balfour, and Sir Herbert a silver platter. -

Forgotten in the Diaspora: the Palestinian Refugees in Egypt

Forgotten in the Diaspora: The Palestinian Refugees in Egypt, 1948-2011 Lubna Ahmady Abdel Aziz Yassin Middle East Studies Center (MEST) Spring, 2013 Thesis Advisor: Dr. Sherene Seikaly Thesis First Reader: Dr. Pascale Ghazaleh Thesis Second Reader: Dr. Hani Sayed 1 Table of Contents I. CHAPTER ONE: PART ONE: INTRODUCTION……………………………………………...…….4 A. PART TWO: THE RISE OF THE PALESTINIAN REFUGEE PROBLEM…………………………………………………………………………………..……………..13 B. AL-NAKBA BETWEEN MYTH AND REALITY…………………………………………………14 C. EGYPTIAN OFFICIAL RESPONSE TO THE PALESTINE CAUSE DURING THE MONARCHAL ERA………………………………………………………………………………………25 D. PALESTINE IN THE EGYPTIAN PRESS DURING THE INTERWAR PERIOD………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….38 E. THE PALESTINIAN REFUGEES IN EGYPT, 1948-1952………………………….……….41 II. CHAPTER TWO: THE NASSER ERA, 1954-1970 A. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND…………………………………………………………………….…45 B. THE EGYPTIAN-PALESTINIAN RELATIONS, 1954-1970……………..………………..49 C. PALESTINIANS AND THE NASEERIST PRESS………………………………………………..71 D. PALESTINIAN SOCIAL ORGANIZATIONS………………………………………………..…..77 E. LEGAL STATUS OF PALESTINIAN REFUGEES IN EGYPT………………………….…...81 III. CHAPTER THREE: THE SADAT ERA, 1970-1981 A. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND……………………………………………………………………….95 B. EGYPTIAN-PALESTINIAN RELATIONS DURING THE SADAT ERA…………………102 C. THE PRESS DURING THE SADAT ERA…………………………………………….……………108 D. PALESTINE IN THE EGYPTIAN PRESS DURING THE SADAT ERA……………….…122 E. THE LEGAL STATUS OF PALESTINIAN REFUGEES DURING THE SADAT ERA……………………………………………………………………………………………………….…129 IV. CHAPTER FOUR: -

The-Balfour-Declaration-Lookstein-Center.Pdf

The Balfour Declaration - November 2, 1917 Celebrating 100 Years There are those who believe that the Balfour Declaration was the most magnanimous (generous) gesture by an imperial nation. Others believe it was the biggest error of judgment that a world power could make. In this unit, we will discover: What was the Balfour Declaration Why the Balfour Declaration was so important How the Balfour Declaration is relevant today 1. Which of the following Declarations have you heard of? a) The United States Declaration of Independence, 1776 b) The Irish Declaration of Independence, 1917 c) The Balfour Declaration, 1917 d) The Israeli Declaration of Independence, 1948 e) The Austrian Declaration of Neutrality, 1955 What was the Balfour Declaration? The Balfour Declaration was a letter written in the name of the British government, by Lord Arthur James Balfour, Britain’s Foreign Secretary, to the leaders of the Zionist Federation. 2. Read the letter: Dear Lord Rothschild, I have much pleasure in conveying to you, on behalf of His Majesty’s Government, the following declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations which has been submitted to, and approved by, the Cabinet. “His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.” I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Federation. -

Nixon, Israel, and the Black September Crisis BRADLEY J

Primary Source Volume IV: Issue I Page 35 The Power of Presence: Nixon, Israel, and the Black September Crisis BRADLEY J. PIERSON lthough the Arab-Israeli conflict has received a considerable amount of scholarly attention in recent years, the A1970 Black September Crisis remains one of the most understudied and misunderstood events of the Cold War era. The existing scholarship on “Black September,” which predominantly views the Crisis as an extension of the 1967 and 1973 Arab-Israeli Wars, fails to analyze the Crisis’ significance within the broader struggle between the Nix- on administration and its Soviet counterparts. While the outbreak of civil war in Jordan was certainly the product of unresolved hostility in the region, the conflict’s escalation to an international confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union was actually the result of a broadening struggle for influence.What began as a regional crisis quickly transformed into what National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger would later call, “a test of the American capacity to control events in the region.”1 This paper will analyze the Nixon Administration’s use of increasingly as- sertive language and behavior to interpret its strategic methodology. Though the United States was hesitant to commit troops to Jordan due to its cumbersome military commitments in Southeast Asia, the Nixon Administration employed a composite of firm diplomatic posturing and the display of overt military signals to publicly demonstrate an uncom- promised military capability in the Middle East. The United States’ handling of the crisis was consistent with the Nixon Administration’s affinity toward heavy-handed diplomacy. -

The Forgotten Regional Landscape of the Sykes-Picot Agreement

LOEVY MACRO (DO NOT DELETE) 4/2/2018 10:42 AM RAILWAYS, PORTS, AND IRRIGATION: THE FORGOTTEN REGIONAL LANDSCAPE OF THE SYKES-PICOT AGREEMENT Karin Loevy ABSTRACT What was the geo-political scale of the Sykes-Picot Agreement of May 1916? What did the British and French mid-level officials who drew lines on its maps imagine as the territorial scope of their negotiations? This Article claims that the Sykes-Picot Agreement cannot be understood strictly as the beginning of a story about territorial division in the Middle East, but also as an end to a story of perceived regional potency. Rather than a blueprint for what would later become the post-war division of the region into artificially created independent states, the Sykes-Picot Agreement was still based on a powerful vision of a broad region that is open for a range of developmental possibilities. Part II of this Article outlines the prewar regional landscape of the agreement in ideas and practices of colonial development in Ottoman territories. Part III outlines the agreement’s war-time regional landscape in inter-imperial negotiations and in the more intimate drafting context, and locates the Sykes-Picot Agreement within a “missed” moment of regional development. I. INTRODUCTION: OPENING TERRITORIAL SPACE ............................ 288 A. Preface: December 1915, at 10 Downing Street .................... 288 B. A Forgotten Regional Landscape ........................................... 290 C. The Sykes-Picot Agreement: A Region Opening-Up for Development ........................................................................... 291 II. PRE-WAR HISTORY OF THE SYKES-PICOT AGREEMENT ................. 296 A. The Context of the Agreement in Pre-war Colonial JSD Program Manager, IILJ Visiting Scholar New York University School of Law; 22 Washington Square North, New York, NY 10001, [email protected]. -

Jerusalem: Legal & (And) Political Dimensions in a Search for Peace

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 12 Issue 1 Article 9 1980 Jerusalem: Legal & (and) Political Dimensions in a Search for Peace Mark I. Gruhin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Mark I. Gruhin, Jerusalem: Legal & (and) Political Dimensions in a Search for Peace, 12 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 169 (1980) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol12/iss1/9 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Volume 12, Number 1, Winter 1980 Jerusalem: Legal & Political Dimensions in a Search for Peace by Mark I. Gruhin* I. INTRODUCTION ANEW ERA of camaraderie has entered the bitter Arab-Israeli conflict as a result of Anwar Sadat's historic visit to Jerusalem and the Camp David Summit. This change in Egyptian attitude" marks a hopeful start in future negotiations between Israel and her neighboring countries. Israel and Egypt have been able to come to terms on most issues concerning the Sinai, but have not been able to reach any agreement concerning the city of Jerusalem. 2 When the Peace Treaty was being signed in Washington, D.C., both Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin made conflicting remarks in their speeches regarding Jerusalem. Anwar Sadat called for the return of East Jerusalem and Arab sovereignty while Menachem Begin spoke of the reunification in 1967 of the Old City (East Jerusalem) with the New City (West Jerusalem).3 Jerusalem, a small tract of land situated in the Judean Hills, thirty- five miles from the Mediterranean Sea,4 is a city which. -

The Arab-Israeli Wars

The Arab-Israeli Wars War and Peace in the Middle East Chaim Herzog THE WAR OF ATTRITION 2 19 scalation, no communique on this aerial encounter was issued, and nor • deed did the Egyptians or Russians mention a word of it in public. There was considerable consternation in the Soviet Union, but the Egyptians nenly rejoiced at the Soviet discomfiture: they heartily disliked their Soviet allies, whose crude, gauche behaviour had created bitter antagonism, and whose officers looked down on the Egyptian officers, treating them with faintly-concealed disdain. The commander of the Soviet Air Defences and the commander of the Soviet Air Force rushed to Egypt on that very day. The cease-fire Meanwhile, political negotiations had been afoot on the basis of the United States' so-called 'Rogers Plan'. Originally proposed by the American Secretary of State, William Rogers, in December 1969, this plan envisaged a peace treaty between Israel, Egypt and Jordan, in which there would be almost complete Israeli withdrawal from occupied territories, leaving open the questions of the Gaza Strip and Sharm El-Sheikh. An acceptance of this plan required an agreement for a cease-fire for a period of three months. Nasser returned from a visit to the Soviet Union in July a frustrated and very sick man. He was beginning to realize the scope of the political cost for Russian involvement in Egypt. The strain and cost of the War of Attrition were beginning to tell, and he believed he could use a cease-fire to advance his military plans. He announced that he was willing to accept the Rogers Plan, and Jordan joined him in accepting a cease-fire.