Jerusalem: Legal & (And) Political Dimensions in a Search for Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Market Update

GLOBAL MARKET UPDATE 22 TO 28 MAY: PAPER SHUFFLING THIS WEEK’S GLOBAL EQUITY MARKET MOVERS Top 3: New Zealand 2.78%, Luxembourg 2.38%, Finland 1.67% DEVELOPED Bottom 3: Italy -1.78%, Belgium -1.35%, Norway -0.99% Top 3: Turkey 3.83%, Brazil 2.95%, China "H" 2.90% EMERGING Bottom 3: Dubai -1.51%, Abu Dhabi -1.41%, Indonesia -1.19% Top 3: Kenya 4.74%, Pakistan 3.74%, Nigeria 3.38% FRONTIER Bottom 3: Tanzania -7.44%, Bermuda -2.54%, Jamaica -2.09% After a 9-month odd bull market, some divergence and loss of momentum has prevailed over recent weeks. Over the next month, a number of policy announcements could shape market direction. In particular: • FED and ECB monetary policy decisions at which the US will likely raise rates and Europe may signal a more hawkish stance on policy. • UK general elections and the start of Brexit negotiations. • Italian electoral reform (setting up an Autumn election) and the conclusion of Greek negotiations with the EU to unlock the latest tranche of funding. under quantitative easing gained greater prominence in UNITED STATES discussions. Specifically, “nearly all policymakers expressed S&P 2,416 +1.43%, 10yr Treasury 2.23% +1.19bps, HY Credit a favourable view” of a plan whereby the bank would Index 327 -3bps, Vix 9.81 -2.23Vol announce limits on the dollar amounts of securities that would not be reinvested each month. These caps would The minutes to the FED’s May meeting contained two then increase every 3 months. “Most participants…judged points of interest: that a change in the committee’s reinvestment policy would likely be appropriate later this year” and that “the 1. -

The-Legal-Status-Of-East-Jerusalem.Pdf

December 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Cover photo: Bab al-Asbat (The Lion’s Gate) and the Old City of Jerusalem. (Photo by: JC Tordai, 2010) This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the European Union. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non- governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Emily Schaeffer for her insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 2. Background ............................................................................................................................ 6 3. Israeli Legislation Following the 1967 Occupation ............................................................ 8 3.1 Applying the Israeli law, jurisdiction and administration to East Jerusalem .................... 8 3.2 The Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel ................................................................... 10 4. The Status -

The Mount Scopus Enclave, 1948–1967

Yfaat Weiss Sovereignty in Miniature: The Mount Scopus Enclave, 1948–1967 Abstract: Contemporary scholarly literature has largely undermined the common perceptions of the term sovereignty, challenging especially those of an exclusive ter- ritorial orientation and offering a wide range of distinct interpretations that relate, among other things, to its performativity. Starting with Leo Gross’ canonical text on the Peace of Westphalia (1948), this article uses new approaches to analyze the policy of the State of Israel on Jerusalem in general and the city’s Mount Scopus enclave in 1948–1967 in particular. The article exposes tactics invoked by Israel in three different sites within the Mount Scopus enclave, demilitarized and under UN control in the heart of the Jordanian-controlled sector of Jerusalem: two Jewish in- stitutions (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Hadassah hospital), the Jerusa- lem British War Cemetery, and the Palestinian village of Issawiya. The idea behind these tactics was to use the Demilitarization Agreement, signed by Israel, Transjor- dan, and the UN on July 7, 1948, to undermine the status of Jerusalem as a Corpus Separatum, as had been proposed in UN Resolution 181 II. The concept of sovereignty stands at the center of numerous academic tracts written in the decades since the end of the Cold War and the partition of Europe. These days, with international attention focused on the question of Jerusalem’s international status – that is, Israel’s sovereignty over the town – there is partic- ularly good reason to examine the broad range of definitions yielded by these discussions. Such an examination can serve as the basis for an informed analy- sis of Israel’s policy in the past and, to some extent, even help clarify its current approach. -

Moving the American Embassy in Israel to Jerusalem: Challenges and Opportunities

MOVING THE AMERICAN EMBASSY IN ISRAEL TO JERUSALEM: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON NATIONAL SECURITY OF THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 8, 2017 Serial No. 115–44 Printed for the use of the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov http://oversight.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 28–071 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 09:17 Jan 19, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\28071.TXT APRIL KING-6430 with DISTILLER COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM Trey Gowdy, South Carolina, Chairman John J. Duncan, Jr., Tennessee Elijah E. Cummings, Maryland, Ranking Darrell E. Issa, California Minority Member Jim Jordan, Ohio Carolyn B. Maloney, New York Mark Sanford, South Carolina Eleanor Holmes Norton, District of Columbia Justin Amash, Michigan Wm. Lacy Clay, Missouri Paul A. Gosar, Arizona Stephen F. Lynch, Massachusetts Scott DesJarlais, Tennessee Jim Cooper, Tennessee Trey Gowdy, South Carolina Gerald E. Connolly, Virginia Blake Farenthold, Texas Robin L. Kelly, Illinois Virginia Foxx, North Carolina Brenda L. Lawrence, Michigan Thomas Massie, Kentucky Bonnie Watson Coleman, New Jersey Mark Meadows, North Carolina Stacey E. Plaskett, Virgin Islands Ron DeSantis, Florida Val Butler Demings, Florida Dennis A. Ross, Florida Raja Krishnamoorthi, Illinois Mark Walker, North Carolina Jamie Raskin, Maryland Rod Blum, Iowa Peter Welch, Vermont Jody B. -

Israeli Settlement Goods

British connections with Israeli Companies involved in the Trade union briefing settlements settlements Key Israeli companies which export settlement products to the Over 50% of Israel’s agricultural produce is imported by UK are: the European Union, of which a large percentage arrives in British stores, including all the main supermarkets. These Agricultural Export Companies: Carmel-Agrexco, Hadiklaim, include: Asda, Tesco, Waitrose, John Lewis, Morrisons, and Mehadrin-Tnuport, Arava, Jordan River, Jordan Plains, Flowers Sainsburys. Direct Other food products: Abady Bakery, Achdut, Adumim Food ISRAELI SETTLEMENT The Soil Association aids the occupation by providing Additives/Frutarom, Amnon & Tamar, Oppenheimer, Shamir certification to settlement products. Salads, Soda Club In December 2009, following significant consumer pressure, Dead Sea Products: Ahava, Dead Sea Laboratories, Intercosma the Department for Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) issued GOODS: BAN THEM, guidelines for supermarkets on settlement labeling — Please note that some of these companies also produce differentiating goods grown in settlements from goods legitimate goods in Israel. It is goods from the illegal grown on Palestinian farms. Although this guidance is not settlements that we want people to boycott. compulsory, many supermarkets are already saying that they don’t buy THEM! will adopt this labeling, so consumers will know if goods Companies working in the are grown in illegal Israeli settlements. DEFRA also stated that companies will be committing an offence -

Legal and Administrative Matters Law from 1970

Systematic dispossession of Palestinian neighborhoods in Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan For many years, there has been an organized governmental effort to take properties in East Jerusalem from Palestinians and transfer them to settlers. In the past it was mainly through the Absentee Properties Law, but today the efforts are done mainly by the use of the Legal and Administrative Matters Law from 1970. Till recently this effort was disastrous for individual families who lost their homes, but now the aim is entire neighborhoods (in Batan al-Hawa and Sheikh Jarrah). Since the horrifying expulsion of the Mughrabi neighborhood from the Old City in 1967 there was no such move in Jerusalem. In recent years there has been an increase in the threat of expulsion hovering over the communities of Sheikh Jarrah and Silwan in East Jerusalem. A wave of eviction lawsuits is being conducted before the courts, with well-organized and well-funded settler groups equipped with direct or indirect assistance from government agencies and the Israeli General Custodian. • Sheikh Jarrah - Umm Haroun (west of Nablus Road) - approximately 45 Palestinian families under threat of evacuation; At least nine of them are in the process of eviction in the courts and at least five others received warning letters in preparation for an evacuation claim. Two families have already been evacuated and replaced by settlers. See map • Sheikh Jarrah - Kerem Alja'oni (east of Nablus Road) – c. 30 Palestinian families under threat of evacuation, at least 11 of which are in the process of eviction in the courts, and 9 families have been evicted and replaced by settlers. -

Arab-Israeli Relations

FACTSHEET Arab-Israeli Relations Sykes-Picot Partition Plan Settlements November 1917 June 1967 1993 - 2000 May 1916 November 1947 1967 - onwards Balfour 1967 War Oslo Accords which to supervise the Suez Canal; at the turn of The Balfour Declaration the 20th century, 80% of the Canal’s shipping be- Prepared by Anna Siodlak, Research Associate longed to the Empire. Britain also believed that they would gain a strategic foothold by establishing a The Balfour Declaration (2 November 1917) was strong Jewish community in Palestine. As occupier, a statement of support by the British Government, British forces could monitor security in Egypt and approved by the War Cabinet, for the establish- protect its colonial and economic interests. ment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. At the time, the region was part of Otto- Economics: Britain anticipated that by encouraging man Syria administered from Damascus. While the communities of European Jews (who were familiar Declaration stated that the civil and religious rights with capitalism and civil organisation) to immigrate of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine to Palestine, entrepreneurialism and development must not be deprived, it triggered a series of events would flourish, creating economic rewards for Brit- 2 that would result in the establishment of the State of ain. Israel forcing thousands of Palestinians to flee their Politics: Britain believed that the establishment of homes. a national home for the Jewish people would foster Who initiated the declaration? sentiments of prestige, respect and gratitude, in- crease its soft power, and reconfirm its place in the The Balfour Declaration was a letter from British post war international order.3 It was also hoped that Foreign Secretary Lord Arthur James Balfour on Russian-Jewish communities would become agents behalf of the British government to Lord Walter of British propaganda and persuade the tsarist gov- Rothschild, a prominent member of the Jewish ernment to support the Allies against Germany. -

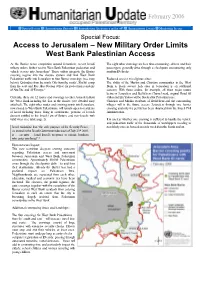

Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access

February 2006 Special Focus Humanitarian Reports Humanitarian Assistance in the oPt Humanitarian Events Monitoring Issues Special Focus: Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access As the Barrier nears completion around Jerusalem, recent Israeli The eight other crossings are less time-consuming - drivers and their military orders further restrict West Bank Palestinian pedestrian and passengers generally drive through a checkpoint encountering only vehicle access into Jerusalem.1 These orders integrate the Barrier random ID checks. crossing regime into the closure system and limit West Bank Palestinian traffic into Jerusalem to four Barrier crossings (see map Reduced access to religious sites: below): Qalandiya from the north, Gilo from the south2, Shu’fat camp The ability of the Muslim and Christian communities in the West from the east and Ras Abu Sbeitan (Olive) for pedestrian residents Bank to freely access holy sites in Jerusalem is an additional of Abu Dis, and Al ‘Eizariya.3 concern. With these orders, for example, all three major routes between Jerusalem and Bethlehem (Tunnel road, original Road 60 Currently, there are 12 routes and crossings to enter Jerusalem from (Gilo) and Ein Yalow) will be blocked for Palestinian use. the West Bank including the four in the Barrier (see detailed map Christian and Muslim residents of Bethlehem and the surrounding attached). The eight other routes and crossing points into Jerusalem, villages will in the future access Jerusalem through one barrier now closed to West Bank Palestinians, will remain open to residents crossing and only if a permit has been obtained from the Israeli Civil of Israel including those living in settlements, persons of Jewish Administration. -

As Mirrored in This Volume of His Letters, the Years 1937-38 Were For

THE LETTERS AND PAPERS OF CHAIM WEIZMANN January 1937 – December 1938 Volume XVIII, Series A Introduction: Aaron Klieman General Editor Barnet Litvinoff, Volume Editor Aaron Klieman, Transaction Books, Rutgers University and Israel Universities Press, Jerusalem, 1979 [Reprinted with express permission from the Weizmann Archives, Rehovot, Israel, by the Center for Israel Education www.israeled.org.] As mirrored in this volume of his letters, the years 1937-38 were for Chaim Weizmann the most critical period of his political life since the weeks preceding the issuance of the Balfour Declaration in November 1917. We observe him at the age of 64 largely drained of physical strength, his diplomatic orientation of collaboration with Great Britain under attack, and his leadership challenged by a generation of younger, militant Zionists. In his own words he was 'a lonely man standing at the end of a road, a via dolorosa. I have no more courage left to face anything—and so much is expected from me.' This situation found its prelude in 1936, when Arab unrest compelled the British Government to undertake a comprehensive reassessment of its policy in Palestine. A Royal Commission headed by Lord Peel was charged with investigating the causes of the disturbances. Weizmann, alert to the implications, took great pains to ensure that the Zionist case was presented with the utmost cogency. As President of the Zionist Organization and of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, he delivered the opening statement on behalf of the Jews to the Royal Commission in Jerusalem on 25 November 1936. He subsequently gave evidence four times in camera, and directed the presentation of evidence by other Zionist witnesses and maintained informal contact with members of the Commission. -

The British Labour Party and Zionism, 1917-1947 / by Fred Lennis Lepkin

THE BRITISH LABOUR PARTY AND ZIONISM: 1917 - 1947 FRED LENNIS LEPKIN BA., University of British Columbia, 196 1 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History @ Fred Lepkin 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 1986 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Name : Fred Lennis Lepkin Degree: M. A. Title of thesis: The British Labour Party and Zionism, - Examining Committee: J. I. Little, Chairman Allan B. CudhgK&n, ior Supervisor . 5- - John Spagnolo, ~upervis&y6mmittee Willig Cleveland, Supepiso$y Committee -Lenard J. Cohen, External Examiner, Associate Professor, Political Science Dept.,' Simon Fraser University Date Approved: August 11, 1986 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay The British Labour Party and Zionism, 1917 - 1947. -

The Jerusalem Embassy Act of 1995

Catholic University Law Review Volume 45 Issue 3 Spring 1996 Article 15 1996 The Jerusalem Embassy Act of 1995 Geoffrey R. Watson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Geoffrey R. Watson, The Jerusalem Embassy Act of 1995, 45 Cath. U. L. Rev. 837 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol45/iss3/15 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE JERUSALEM EMBASSY ACT OF 1995 Geoffrey R. Watson * Congress has voted to move the U.S. Embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. On October 24, 1995-the day of the Conference on Jeru- salem here at the Columbus School of Law of The Catholic University of America-Congress passed the Jerusalem Embassy Act of 1995.1 The President took no action on the Act, allowing it to enter into force on November 8, 1995.2 The Act states that a United States Embassy to Israel should be established in Jerusalem by May 31, 1999, and it provides for a fifty percent cut in the State Department's building budget if the Embassy is not opened by that time.' The Act permits the President to waive the budget cut for successive six-month periods if the President determines it is necessary to protect the "national security interests of the United States."' In these pages and elsewhere, several contributors to this symposium have addressed the policy questions raised by the Act.5 I will focus on the Act's interpretation. -

Jerusalem: City of Dreams, City of Sorrows

1 JERUSALEM: CITY OF DREAMS, CITY OF SORROWS More than ever before, urban historians tell us that global cities tend to look very much alike. For U.S. students. the“ look alike” perspective makes it more difficult to empathize with and to understand cultures and societies other than their own. The admittedly superficial similarities of global cities with U.S. ones leads to misunderstandings and confusion. The multiplicity of cybercafés, high-rise buildings, bars and discothèques, international hotels, restaurants, and boutique retailers in shopping malls and multiplex cinemas gives these global cities the appearances of familiarity. The ubiquity of schools, university campuses, signs, streetlights, and urban transportation systems can only add to an outsider’s “cultural and social blindness.” Prevailing U.S. learning goals that underscore American values of individualism, self-confidence, and material comfort are, more often than not, obstacles for any quick study or understanding of world cultures and societies by visiting U.S. student and faculty.1 Therefore, international educators need to look for and find ways in which their students are able to look beyond the veneer of the modern global city through careful program planning and learning strategies that seek to affect the students in their “reading and learning” about these fertile centers of liberal learning. As the students become acquainted with the streets, neighborhoods, and urban centers of their global city, their understanding of its ways and habits is embellished and enriched by the walls, neighborhoods, institutions, and archaeological sites that might otherwise cause them their “cultural and social blindness.” Jerusalem is more than an intriguing global historical city.