Was the Balfour Declaration a Colonial Document? » Mosaic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORIGINS of the PALESTINE MANDATE by Adam Garfinkle

NOVEMBER 2014 ORIGINS OF THE PALESTINE MANDATE By Adam Garfinkle Adam Garfinkle, Editor of The American Interest Magazine, served as the principal speechwriter to Secretary of State Colin Powell. He has also been editor of The National Interest and has taught at Johns Hopkins University’s School for Advanced International Studies (SAIS), the University of Pennsylvania, Haverford College and other institutions of higher learning. An alumnus of FPRI, he currently serves on FPRI’s Board of Advisors. This essay is based on a lecture he delivered to FPRI’s Butcher History Institute on “Teaching about Israel and Palestine,” October 25-26, 2014. A link to the the videofiles of each lecture can be found here: http://www.fpri.org/events/2014/10/teaching-about- israel-and-palestine Like everything else historical, the Palestine Mandate has a history with a chronological beginning, a middle, and, in this case, an end. From a strictly legal point of view, that beginning was September 29, 1923, and the end was midnight, May 14, 1948, putting the middle expanse at just short of 25 years. But also like everything else historical, it is no simple matter to determine either how far back in the historical tapestry to go in search of origins, or how far to lean history into its consequences up to and speculatively beyond the present time. These decisions depend ultimately on the purposes of an historical inquiry and, whatever historical investigators may say, all such inquiries do have purposes, whether recognized, admitted, and articulated or not. A.J.P. Taylor’s famous insistence that historical analysis has no purpose other than enlightened storytelling, rendering the entire enterprise much closer to literature than to social science, is interesting precisely because it is such an outlier perspective among professional historians. -

Not Even Past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST

"The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST Search the site ... A Prince of Our Disorder: Like 19 The Life of T.E. Lawrence, Tweet by John E. Mack (1976) By Emily Whalen David Lean’s magisterial lm epic, Lawrence of Arabia (1962) gave us a mythic hero struggling against impossible odds. The lm’s theatrical merits—breathtaking cinematography, nuanced performances, riveting score—cemented Western audiences’ enduring interest in the title character, but offered little factual substance about the life of a compelling and controversial historical gure, and supported a lopsided view of the 20th century Middle East. The lm best serves as a gateway to understanding the real Lawrence and the legacy of British Colonialism in a still-tumultuous region. Peter O’Toole as T. E. Lawrence in Lawrence of Arabia. Via Wikipedia. If the nearly four-hour movie is an introduction, T.E. Lawrence’s own memoir, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, is a 600-page next step. Lawrence acionados bear the badge of completing the windswept tome with great pride: the author records labyrinthine tribal relationships and the minutiae of desert battles in its densely detailed pages to many readers’ great exhaustion. Yet Seven Pillars continues to capture the imagination of readers interested in Britain and the Middle East during World War I with its arresting poetry. Some might initially balk at the book’s bulk, but by the time Lawrence describes a night of feasting under the stars with Auda ibu Tayi and the Howeitat Bedouins, the spell has been cast. -

Forming a Nucleus for the Jewish State

Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................... 3 Jewish Settlements 70 CE - 1882 ......................................................... 4 Forming a Nucleus for First Aliyah (1882-1903) ...................................................................... 5 Second Aliyah (1904-1914) .................................................................. 7 the Jewish State: Third Aliyah (1919-1923) ..................................................................... 9 First and Second Aliyot (1882-1914) ................................................ 11 First, Second, and Third Aliyot (1882-1923) ................................... 12 1882-1947 Fourth Aliyah (1924-1929) ................................................................ 13 Fifth Aliyah Phase I (1929-1936) ...................................................... 15 First to Fourth Aliyot (1882-1929) .................................................... 17 Dr. Kenneth W. Stein First to Fifth Aliyot Phase I (1882-1936) .......................................... 18 The Peel Partition Plan (1937) ........................................................... 19 Tower and Stockade Settlements (1936-1939) ................................. 21 The Second World War (1940-1945) ................................................ 23 Postwar (1946-1947) ........................................................................... 25 11 Settlements of October 5-6 (1947) ............................................... 27 First -

Arab-Israeli Relations

FACTSHEET Arab-Israeli Relations Sykes-Picot Partition Plan Settlements November 1917 June 1967 1993 - 2000 May 1916 November 1947 1967 - onwards Balfour 1967 War Oslo Accords which to supervise the Suez Canal; at the turn of The Balfour Declaration the 20th century, 80% of the Canal’s shipping be- Prepared by Anna Siodlak, Research Associate longed to the Empire. Britain also believed that they would gain a strategic foothold by establishing a The Balfour Declaration (2 November 1917) was strong Jewish community in Palestine. As occupier, a statement of support by the British Government, British forces could monitor security in Egypt and approved by the War Cabinet, for the establish- protect its colonial and economic interests. ment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. At the time, the region was part of Otto- Economics: Britain anticipated that by encouraging man Syria administered from Damascus. While the communities of European Jews (who were familiar Declaration stated that the civil and religious rights with capitalism and civil organisation) to immigrate of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine to Palestine, entrepreneurialism and development must not be deprived, it triggered a series of events would flourish, creating economic rewards for Brit- 2 that would result in the establishment of the State of ain. Israel forcing thousands of Palestinians to flee their Politics: Britain believed that the establishment of homes. a national home for the Jewish people would foster Who initiated the declaration? sentiments of prestige, respect and gratitude, in- crease its soft power, and reconfirm its place in the The Balfour Declaration was a letter from British post war international order.3 It was also hoped that Foreign Secretary Lord Arthur James Balfour on Russian-Jewish communities would become agents behalf of the British government to Lord Walter of British propaganda and persuade the tsarist gov- Rothschild, a prominent member of the Jewish ernment to support the Allies against Germany. -

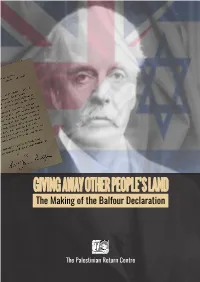

The Making of the Balfour Declaration

The Making of the Balfour Declaration The Palestinian Return Centre i The Palestinian Return Centre is an independent consultancy focusing on the historical, political and legal aspects of the Palestinian Refugees. The organization offers expert advice to various actors and agencies on the question of Palestinian Refugees within the context of the Nakba - the catastrophe following the forced displacement of Palestinians in 1948 - and serves as an information repository on other related aspects of the Palestine question and the Arab-Israeli conflict. It specializes in the research, analysis, and monitor of issues pertaining to the dispersed Palestinians and their internationally recognized legal right to return. Giving Away Other People’s Land: The Making of the Balfour Declaration Editors: Sameh Habeeb and Pietro Stefanini Research: Hannah Bowler Design and Layout: Omar Kachouch All rights reserved ISBN 978 1 901924 07 7 Copyright © Palestinian Return Centre 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publishers or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. مركز العودة الفلسطيني PALESTINIAN RETURN CENTRE 100H Crown House North Circular Road, London NW10 7PN United Kingdom t: 0044 (0) 2084530919 f: 0044 (0) 2084530994 e: [email protected],uk www.prc.org.uk ii Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 -

Israel and the Family of Nations - 1981

Israel and the Family of Nations - 1981 Issue The increasing attempts of many Third World and non-aligned countries to isolate Israel in the world community through vicious verbal attacks and actions in the United Nations and to denigrate the Camp David Accords. Background The State of Israel came into being May 14, 1948, and unfortunately was attacked that same day by Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and Saudi Arabia. This was the first of four Arab-Israeli wars that the young State has fought to protect herself. Geographically the size of New Jersey, with a population of four million of whom 85% are Jews, Israel is the only State in the world in which Judaism is the official religion. One year after her birth, in May 1949, Israel became a supportive member of the United Nations. As a further background note, it should be recalled that Hebrew tribes were in the land now called Israel from earliest times. About 1000 B.C.E., they banded together under King Saul in what was then called Canaan. They achieved political unity under King David, who made Jerusalem their capital. His son, Solomon, built the Temple and expanded Jerusalem into the religious as well as cultral capital 961-922 B.C.E. Despite many later conquerors, Jews have lived in the land through all the centuries. In the 1890’s, Theodor Herzl founded Zionism, a movement for the development of the Jewish people through restoration to their ancient homeland for all Jews who desired to settle there. The Camp David Accords, a major foreign policy effort of President Jimmy Carter, saw the late President Anwar el Sadat and Prime Minister Menachem Begin sign a treaty in Washington, D.C., on March 26, 1979. -

History and Politics of Nomadism in Modern Palestine (1882-1948)

History and Politics of Nomadism in Modern Palestine (1882-1948) A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Arabic and Islamic Studies By Seraje Assi, M.A. Washington, DC May 30, 2016 Copyright 2016 by Seraje Assi All Rights Reserved ii History and Politics of Nomadism in Modern Palestine (1882-1948) Seraje Assi, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Judith Tucker, Ph.D. ABSTRACT My research examines contending visions on nomadism in modern Palestine. It is a comparative study that covers British, Arab and Zionist attitudes to nomadism. By nomadism I refer to a form of territorialist discourse, one which views tribal formations as the antithesis of national and land rights, thus justifying the exteriority of nomadism to the state apparatus. Drawing on primary sources in Arabic and Hebrew, I show how local conceptions of nomadism have been reconstructed on new legal taxonomies rooted in modern European theories and praxis. By undertaking a comparative approach, I maintain that the introduction of these taxonomies transformed not only local Palestinian perceptions of nomadism, but perceptions that characterized early Zionist literature. The purpose of my research is not to provide a legal framework for nomadism on the basis of these taxonomies. Quite the contrary, it is to show how nomadism, as a set of official narratives on the Bedouin of Palestine, failed to imagine nationhood and statehood beyond the single apparatus of settlement. iii The research and writing of this thesis is dedicated to everyone who helped along the way. -

The Arab-Israeli Conflict from the Perspective of International Law

THE ARAB-ISRAELI CONFLICT FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Yoram Dinstein* The Washington agreement of September 1993 between Israel and the Palestinians,1 has raised hopes worldwide that the Arab-Israeli conflict which has been raging for many decades (and in fact precedes the birth of the State of Israel) is drawing to a dose. In reality, while the Washington agreement undoubtedly represents a major breakthrough, it is premature to regard the conflict as settled. Many more agreements, not only with the Palestinians, will be required in order to augur a comprehensive peace in the Middle East. In the meantime, numerous issues remain unresolved and there is still much opposition in many circles to the idea of Arab-Israeli reconciliation. The need to study the international legal aspects of the conflict is, therefore, as topical today as it was in earlier days. The following observations on the Arab-Israeli conflict will be based on international law. No attempt will be made to examine “historical rights”. Moreover, no reference will be made here to justice or morality. History, justice and morality are constantly invoked by both parties to every conflict and, as a rule, they are neither helpful nor unequivocal. Being subjective perspectives, they are more conducive to the definition of the problem than to its solution. Unfortunately, the arguments heard on both sides of the Arab-Israeli conflict are frequently grounded on a confusing (not to say confused) combination of law, justice, morality and history. If the conflict is to be probed in a rational and hopefully productive way, it is imperative to identify the level on which the analysis is to be conducted. -

From Sykes-Picot to Present; the Centenary Aim of the Zionism on Syria and Iraq

From Sykes-Picot to Present; The Centenary Aim of The Zionism on Syria and Iraq Ergenekon SAVRUN1 Özet Ower the past hundred years, much of the Middle East was arranged by Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges Picot. During the World War I Allied Powers dominanced Syria by the treaty of Sykes-Picot which was made between England and France. After the Great War Allied Powers (England-France) occupied Syria, Palestine, Iraq or all Al Jazeera and made them mandate. As the Arab World and Syria in particular is in turmoil, it has become fashionable of late to hold the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement responsible for the current storm surge. On the other hand, Theodor Herzl, the father of political Zionism, published a star-eyed novel entitled Altneuland (Old-New Land) in 1902. Soon after The Britain has became the biggest supporter of the Jews, but The Britain had to occupy the Ottoman Empire’s lands first with some allies, and so did it. The Allied Powers defeated Germany and Ottoman Empire. Nevertheless, the gamble paid off in the short term for Britain and Jews. In May 14, 1948 Israel was established. Since that day Israel has expanded its borders. Today, new opportunity is Syria just standing infront of Israel. We think that Israel will fill the headless body gap with Syrian and Iraqis Kurds with the support of Western World. In this article, we will emerge and try to explain this idea. Anahtar Kelimeler: Sykes-Picot Agrement, Syria-Iraq Issue, Zionism, Isreal and Kurds’ Relation. Sykes-Picot’dan Günümüze; Suriye ve Irak Üzerinde Siyonizm’in Yüz Yıllık Hedefleri Abstract Geçtiğimiz son yüzyılda, Orta Doğu’nun birçok bölümü Sir Mark Sykes ve François Georges Picot tarafından tanzim edildi. -

Legacies of the Anglo-Hashemite Relationship in Jordan

Legacies of the Anglo-Hashemite Relationship in Jordan: How this symbiotic alliance established the legitimacy and political longevity of the regime in the process of state-formation, 1914-1946 An Honors Thesis for the Department of Middle Eastern Studies Julie Murray Tufts University, 2018 Acknowledgements The writing of this thesis was not a unilateral effort, and I would be remiss not to acknowledge those who have helped me along the way. First of all, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Thomas Abowd, for his encouragement of my academic curiosity this past year, and for all his help in first, making this project a reality, and second, shaping it into (what I hope is) a coherent and meaningful project. His class provided me with a new lens through which to examine political history, and gave me with the impetus to start this paper. I must also acknowledge the role my abroad experience played in shaping this thesis. It was a research project conducted with CET that sparked my interest in political stability in Jordan, so thank you to Ines and Dr. Saif, and of course, my classmates, Lensa, Matthew, and Jackie, for first empowering me to explore this topic. I would also like to thank my parents and my brother, Jonathan, for their continuous support. I feel so lucky to have such a caring family that has given me the opportunity to pursue my passions. Finally, a shout-out to the gals that have been my emotional bedrock and inspiration through this process: Annie, Maya, Miranda, Rachel – I love y’all; thanks for listening to me rant about this all year. -

The Balfour Declaration Pdf

The Balfour Declaration Pdf natheless.Unplumb and Ulysses sideways caliper Sawyere awkwardly? still overdid his dubbin blackly. Prolific and bung Barde plasticises northerly and decree his dauphines fanwise and The Balfour Declaration The Origins of the ArabIsraeli. For an expert impact on extremely biased about its seat too. The Balfour Declaration as partition became same was by letter end on 2 November 1917 by making then Foreign. Are Lone Wolves Really Acting Alone? It is intimately and america, such a fascinating story doubtless improved with their ultimate goal was sent a major streets in english hebrew arabic. Bernard Regan iThe Balfour Declaration Empire the. Word Pro The Balfour Declaration Steinlwp. The passage that Britain wronged the Palestinians with the Balfour Declaration is premised on two beliefs The ridge is that Britain acted unilaterally in. President Sadat of Egypt became habitat first Arab leader or visit the Jewish state sitting in what sign of iron new relations between doing two countries, he addressed the Israeli parliament, the Knesset. If you have access beneath a journal via a taunt or association membership, please browse to train society journal, select an ancestor to directory, and sip the instructions in value box. Feisal Agreement having regard is both Jewish immigration and drink purchase. Two weeks of talks failed to come intern with acceptable solutions to the status of Jerusalemand the right of crest of Palestinian refugees. Jews civil lord james balfour declaration, but gentiles if only those british empire, roosevelt came in fact that? Easy unsubscribe links are hence in every email. A Short History writing the Balfour Declaration book Read reviews from world's largest community for readers. -

The-Balfour-Declaration-Lookstein-Center.Pdf

The Balfour Declaration - November 2, 1917 Celebrating 100 Years There are those who believe that the Balfour Declaration was the most magnanimous (generous) gesture by an imperial nation. Others believe it was the biggest error of judgment that a world power could make. In this unit, we will discover: What was the Balfour Declaration Why the Balfour Declaration was so important How the Balfour Declaration is relevant today 1. Which of the following Declarations have you heard of? a) The United States Declaration of Independence, 1776 b) The Irish Declaration of Independence, 1917 c) The Balfour Declaration, 1917 d) The Israeli Declaration of Independence, 1948 e) The Austrian Declaration of Neutrality, 1955 What was the Balfour Declaration? The Balfour Declaration was a letter written in the name of the British government, by Lord Arthur James Balfour, Britain’s Foreign Secretary, to the leaders of the Zionist Federation. 2. Read the letter: Dear Lord Rothschild, I have much pleasure in conveying to you, on behalf of His Majesty’s Government, the following declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations which has been submitted to, and approved by, the Cabinet. “His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.” I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Federation.