The Current Situation.P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pta and Hand Tools

Precision, Quality, Innovation PTA AND HAND TOOLS Hole Saws Hacksaws Jig Saws Reciprocating Saws Portable Band Saws Measuring Tapes Utility Knives Levels Plumb Bobs Chalk Rules & Squares Calipers Protractors Punches Shop Tools Lubricant Catalog 71 PRECISION, QUALITY, iNNOVATiON For more than 135 years, manufacturers, builders and craftsmen worldwide have depended upon precision tools and saws from The L.S. Starrett Company to ensure the consistent quality of their work. They know that the Starrett name on a saw blade, hand tool or measuring tool ensures exceptional quality, innovative products and expert technical assistance. With strict quality control, state-of-the-art equipment and an ongoing commitment to producing superior tools, the thousands of products in today's Starrett line continue to be the most accurate, robust and durable tools available. This catalog features those tools most widely used on a jobsite or in a workshop environment. 2 hole saws Our new line includes the Fast Cut and Deep Cut bi-metal saws, and application-specific hole saws engineered specifically for certain materials, power tools and jobs. A full line of accessories, including Quick-Hitch™ arbors, pilot drills and protective cowls, enables you to optimise each job with safe, cost efficient solutions. 09 hacksaws Hacksaw Safe-Flex® and Grey-Flex® blades and frames, Redstripe® power hack blades, compass and PVC saws to assist you with all of your hand sawing needs. 31 jig saws Our Unified Shank® jig saws are developed for wood, metal and multi-purpose cutting. The Starrett bi-metal unique® saw technology provides our saws with 170% greater resistance to breakage, cut faster and last longer than other saws. -

24 July 2019 1 Logistics Information INEB Conference 2019 Deer Park

Update: 24 July 2019 Logistics Information INEB Conference 2019 Deer Park Institute, Bir, India Event date and venue: 21 October – Visit Main Temple, McLeod Ganj, Dharamsala 22-24 October – INEB Conference, Deer Park Institute, Bir 25 October – AC/EC meeting – Deer Park Institute, Bir 21 October 2019 Main Temple, McLeod Ganj, Dharamsala Location: https://goo.gl/maps/683MKzAZePgBtUB37 Travel - How to get to McLeod Ganj from New Delhi By plane From New Delhi, book a ticket through either the Air India/Alliance Air (www.airindia.in) or Spicejet (www.spicejet.com) that flies to Kangra airport (DHM), which is about 20 km from McLeod Ganj. Then take a taxi from the Kangra airport to McLeod Ganj which costs approximately Rs900 one way and it takes around 45 minutes. By bus There are several bus companies running from New Delhi to McLeod Ganj. It’s recommended to use the government bus called, HRTC (Himachal Road Transport Corporation). You can book a ticket online directly via its website https://hrtchp.com (Indian phone number required) or a reliable agent’s website www.redbus.in at similar costs - around Rs850 (non-AC bus) to Rs1,390 (AC volvo bus). The trip on a HRTC bus takes about 12 hours from ISBT (Inter State Bus Terminal) at Kashmere Gate in New Delhi to McLeod Ganj bus station (2 min walk to the main square). Most buses travel at night with two stops for food and toilets. By train There is no train station in Dharamsala or McLeod Ganj. You can take train from New Delhi to the Pathankot Cantonment railway station (Pathankot Cantt), then take a taxi to McLeod Ganj (Rs3,000, 2.5 hours). -

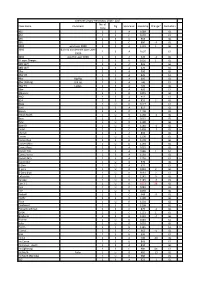

Central-Karachi

Central-Karachi 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Total Budget Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 1-Kalyana 408130186 GBELS - Elementary Elementary Boys 20,253 4,051 16,202 4,051 4,051 16,202 64,808 16,202 81,010 2 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 4-Ghodhra 408130163 GBLSS - 11-G NEW KARACHI Middle Boys 24,147 4,829 19,318 4,829 4,829 19,318 77,271 19,318 96,589 3 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 4-Ghodhra 408130167 GBLSS - MEHDI Middle Boys 11,758 2,352 9,406 2,352 2,352 9,406 37,625 9,406 47,031 4 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 4-Ghodhra 408130176 GBELS - MATHODIST Elementary Boys 20,492 4,098 12,295 8,197 4,098 16,394 65,576 16,394 81,970 5 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 6-Hakim Ahsan 408130205 GBELS - PIXY DALE 2 Registred as a Seconda Elementary Girls 61,338 12,268 49,070 12,268 12,268 49,070 196,281 49,070 245,351 6 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 9-Khameeso Goth 408130174 GBLSS - KHAMISO GOTH Middle Mixed 6,962 1,392 5,569 1,392 1,392 5,569 22,278 5,569 27,847 7 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 10-Mustafa Colony 408130160 GBLSS - FARZANA Middle Boys 11,678 2,336 9,342 2,336 2,336 9,342 37,369 9,342 46,711 8 Central Karachi New Karachi Town 10-Mustafa Colony 408130166 GBLSS - 5/J Middle Boys 28,064 5,613 16,838 11,226 5,613 22,451 89,804 22,451 112,256 9 Central Karachi New Karachi -

Accessories 1

MOTOMAN Accessories 1 Accessories Program www.yaskawa.eu.com Masters of Robotics, Motion and Control Contents Accessories Cable Retraction System for Teach Pendants ..................................................... 5 Media Packages suitable for all Applications ....................................................... 7 Robot Pedestals and Robot Base Plates for MOTOMAN Robots ............................................................ 9 External Drive Axes Packages for MOTOMAN Robots with DX200 Controller ....................... 17 Touch Sensor Search Sensor with Welding Wire .......................................... 21 MotoFit Force Control Assembly Tool ................................................ 23 YASKAWA Vision System Camera & Software MotoSight2D .......................................... 25 Fieldbus Systems .................................................................. 27 4 Accessories MOTOMAN Accessories 5 Cable Retraction System for Teach Pendants The automatic YASKAWA cable retraction system has been specially developed for the connecting cables of industrial robot teach pendants. This system is used to improve work safety in the production area and is a recognized accident prevention measure. The stable housing is made of impactresistant plastic, while the mounting bracket is made of steel plate, enabling alignment of the retraction system housing in the direction in which the cable is pulled out. The cable deflection pulley is fitted with a spring element for cable retraction. Additionally, a releas- able cable -

Great Lakes Handicaps 2018-19 05/12/18

Great Lakes Handicaps 2018-19 05/12/18 Type Boat Class Handicap RYA / Class 2018/19 Difference to Change from Notes: See key below Status Handicap Handicap RYA / Class 2017/18 D 405 RYA - A 1089 1089 D 420 RYA 1111 1086 -25 16 Note 2: Based on SWS data D 470 Class 973 973 10 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D 505 RYA 903 878 -25 -2 Note 2: Based on SWS data D 2000 RYA 1109 1109 2 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D 3000 Class 1007 1007 D 4000 RYA 917 917 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D 12 sqm Sharpie RYA - A 1026 1026 D 12ft Skiff Class 879 857 -22 22 Note 4: Based on boat specs D 18ft Skiff Class 675 670 -5 Note 4: Based on boat specs K 2.4m RYA - A 1240 1230 -10 10 Note 3: Based on club data D 29er RYA 912 905 -7 5 Note 2: Based on SWS data D 29er XX Class 830 820 -10 Note 4: Based on boat specs D 49er RYA 697 697 2 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D 49er (Old rig) Class 740 740 D 49er FX Class ?? 720 Note 4: Based on boat specs D 59er Class 905 905 M A Class Classic RYA 684 684 M A Class Foiling SCHRS n/a 656 Note 4: Based on boat specs D Albacore RYA 1038 1055 17 Note 2: Based on SWS data D AltO RYA 920 920 3 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D B14 RYA - E 862 857 -5 5 Note 2: Based on SWS data D Blaze RYA 1027 1027 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D Boss Class 847 832 -15 15 Note 4: Based on boat specs D Bosun RYA - A 1198 1198 D British Moth RYA 1155 1155 D Buzz RYA - E 1026 1026 3 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D Byte Class 1190 1190 D Byte CI Class ?? 1177 Note 4: Based on boat specs D Byte CII RYA 1144 1144 -3 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D Cadet RYA -

Great Lakes Handicaps 2020-21.Xls

Great Lakes Handicaps 2020-21 01/10/2020 Type Boat Class Handicap RYA / Class Great Lakes Difference to Change from Notes for handicap changes: Status Handicap Handicap RYA / Class 2019/20 See key below D 405 RYA - A 1089 1089 D 420 RYA 1105 1083 -22 -3 Note 2: Based on SWS data D 470 RYA - A 973 973 D 505 RYA 903 883 -20 5 Note 2: Based on SWS data D 2000 RYA 1114 1090 -24 -10 Note 2: Based on SWS data D 3000 Class 1007 1007 D 4000 RYA - A 917 917 D 12 sqm Sharpie RYA - A 1026 1026 D 12ft Skiff Class 879 868 -11 Note 4: Based on boat specs D 18ft Skiff Class 675 675 K 2.4m RYA - A 1240 1230 -10 Note 3: Based on club data D 29er RYA 903 903 -4 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D 29er XX Class 830 830 D 49er RYA - A 697 697 D 49er (Old rig) Class 740 740 D 49er FX Class ?? 720 D 59er Class 905 905 M A Class Classic RYA 684 684 M A Class Foiling SCHRS n/a 641 -15 Note 4: Based on boat specs D Albacore RYA 1040 1053 13 -2 Note 2: Based on SWS data D AltO RYA - A 926 926 D B14 RYA - E 860 860 D Blaze RYA 1033 1033 2 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D Boss RYA - A 847 847 D Bosun RYA - A 1198 1198 D British Moth RYA 1160 1155 -5 D Buzz RYA - A 1030 1030 D Byte RYA - A 1190 1190 D Byte CI RYA - E 1215 1215 38 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D Byte CII RYA 1135 1135 -3 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class D Cadet RYA - E 1430 1435 5 M Catapult RYA 898 898 -5 Note 1: Based on RYA / Class M Challenger RYA 1173 1162 -11 Note 4: Based on boat specs D Cherub RYA - A 903 890 -13 Note 4: Based on boat specs D Cherub 97 Class ?? 970 Note 4: Based on boat specs D Cherub -

Robot Pedestals and Robot Base Plates for MOTOMAN Robots

Robot pedestals and Robot base plates for MOTOMAN robots As a robot manufacturer with our own systems engineering facilities, we are able to offer not just the robot, but also matching pedestals or base plates from a single source. This not only saves you organizational effort, but also ensures that you receive coordinated products that can be used directly. KEY BENEFITS • Suitable for our most common robot models • Wide range to meet your requirements • High-quality painted steel structure • Simple fastening by means of anchor bolts/bolted connections • Height-adjustable • Re-usable with the same robot model YASKAWA Europe GmbH Robotics Yaskawastraße 1 85391 Allershausen, Germany Tel. +49 (0) 8166 90-0 www.yaskawa.eu.com [email protected] www.yaskawa.eu.com Robot pedestals XS-series B C • Robot pedestals for MOTOMAN robots • Steel structure, painted, RAL 5005 (blue) • Fastening by means of anchor bolts/bolted connections • Height-adjustable For the following robot types: A MH5S II, MH5LS II, MH5F, MH5LF, GP7, GP8 E G L F D XS-series Robot pedestals A B C D E F G L Weight SAP XS-RS200 200 240 240 400 400 320 320 4 x Ø 27 37 172543 XS-RS300 308 236 236 400 400 340 340 4 x Ø 28 39 149625 XS-RS400 408 236 236 400 400 340 340 4 x Ø 28 44 167318 XS-RS500 500 240 240 400 400 320 320 4 x Ø 27 50 172536 XS-RS600 608 236 236 400 400 340 340 4 x Ø 28 58 146090 XS-RS900 908 236 236 400 400 340 340 4 x Ø 28 72 153560 Robot pedestals S-series B C • Robot pedestals for MOTOMAN robots • Steel structure, painted, RAL 5005 (blue) • Fastening by -

Class Name Comment No. of Crew Rig Spinnaker Handicap Change

Grafham Dinghy Handicaps, 2016 - 2017 No. of Class Name Comment Rig Spinnaker Handicap Change* Derivation Crew 405 2 S A 1089 GL 420 2 S C 1070 GL 470 2 S C 963 GL 505 2 S C 880 -3 GL 2000 was Laser 2000 2 S A 1101 1 GL 3000 Built by Vandercraft (was Laser 2 S A 1007 GL 3000) 4000 was the Laser 4000 2 S A 920 -2 GL 12 sqm Sharpie 2 S 0 1026 1 GL 12ft Skiff 3 S A 835 GL 18ft Skiff 2 S A 670 GL x 29er 2 S A 900 GL 29er XX 2 S A 820 GL 49er Big Rig 2 S A 695 GL 49er (Old rig) Old rig 2 S A 740 GL 49er FX Ladies 2 S A 720 GL 59er 2 S A 905 GL Albacore 2 S 0 1055 GL AltO 2 S A 912 GL B14 2 S A 852 2 GL Blaze 1 U 0 1027 GL Boss 2 S A 817 GL Bosun 2 S 0 1198 GL British Moth 1 U 0 1158 -2 GL Buzz 2 S A 1015 GL Byte 1 U 0 1190 GL Byte CII 1 U 0 1148 -2 GL Cadet 2 S C 1428 -7 GL x Cherub 2 S A 890 GL Comet 1 U 0 1200 GL Comet Duo 2 S 0 1178 GL Comet Mino 1 U 0 1193 GL Comet Race 2 S A 1025 GL Comet Trio 2 S A 1086 1 GL Comet Versa 2 S A 1150 GL Comet Zero 2 S A 1250 GL x Contender 1 U 0 976 GL D-One 1 U A 971 GL D-Zero 1 U 0 1033 2 GL D-Zero Blue 1 U 0 1061 2 GL Enterprise 2 S 0 1145 3 GL Europe 1 U 0 1145 -3 GL Farr 3.7 1 U 0 1053 38 GL Finn 1 U 0 1042 GL Fire 1 U 0 1050 GL Fireball 2 S C 948 -5 GL Firefly 2 S 0 1190 GL Flash 1 U 0 1101 GL Fleetwind 2 S 0 1268 GL x Flying Dutchman 2 S C 879 -1 GL GP14 2 S C 1131 1 GL Graduate 2 S 0 1132 -4 GL Hadron 1 U 0 1040 GL Halo 1 U 0 1010 GL Heron 1 S 0 1345 GL x Hornet 2 S C 962 -1 GL Icon 2 S 0 990 GL Int 14 2 S A 700 -20 GL Int Canoe 1 S 0 893 GL Int Canoe - Asym 1 S A 840 GL Int Lightning 3 S C 980 -

Rapid Livelihoods Assessment in Coastal Ampara & Batticaloa Districts, Sri Lanka

RAPID LIVELIHOODS ASSESSMENT IN COASTAL AMPARA & BATTICALOA DISTRICTS, SRI LANKA 18th January, 2005 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Save the Children carried out a rapid livelihoods assessment in coastal areas of Ampara and Batticaloa districts between January 5th and 11th to acquire a basic understanding of the different economic activities undertaken prior to the December 26th tsunami within affected communities and nearby towns and villages. The information will be used primarily to inform SC’s own interventions, but may also be of interest to other agencies working in this sector. Information was gathered using qualitative semi-structured interviews with individuals and small groups of purposively-sampled livelihood groups. It is acknowledged that information is incomplete, but it is hoped that the qualitative and contextual information here will assist in interpreting more quantitative data gathered by other agencies. For the population affected by damage to their homes, repair and reconstruction of housing was consistently listed as the top priority in the recovery process, and in many cases is a necessary first step before they can focus their energies of income-earning activities. The assessment confirmed that the largest affected group in these areas were fishermen, but highlights that there are at least 4 categories of fishermen, with different arrangements for payment and sharing of fishing catches, and with very different pre-tsunami incomes. For this group, repair or replacement of fishing boats and equipment is a clear priority. Unskilled casual labourers form a substantial part of the population, and are at the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum. They were employed in a variety of activities, some of which are seasonal, such as house/ garden cleaning, assisting masons and carpenters, assisting fishermen, and harvesting nearby rice fields. -

Latest Catalogue

e-Range.lk Catalogue 3 Volume 1 Issue 18th May 2021 www.e-Range.lk E-mail: [email protected] Call & WhatsApp – 0777 799682 /1A Full Range Inside Your Product Catalogue Þ Baby Care Þ Women’s Care At E-Range we offer our price match promise, so Þ Home Care you don’t have to compromise on service to get Þ Pet Care the very best deals. Þ Stationery & Party Cupboard *T&C’s apply Þ Men’s Care Þ Food Cupboard Þ Health Care Explore a wide range of products inside “Shop More & Spend Less” Wide Range of Shop for Rs 5,000 & get 10% off World Leading Shop for Rs 10,000 & get 15% off Brands. Shop for Rs 20,000 & get 20% off We Deliver to your *Free Delivery on orders above Rs 5,000 door, speak to us erange.lk eRangeSL today! e-Range Page 1 Baby Care Johnson’s Johnson’s Baby Bath Johnson’s Johnson’s Baby time Gift Set Baby Bath Baby Bath Bedtime 500ml 300ml Gift Set 6 Items Rs6500 Rs4000 Rs1650 Rs900 Johnson’s Baby Johnson’s Baby Baby Johnson’s Baby Johnson’s Baby Shampoo Lotion with Coconut Lotion with Oil Honey Soap 4 Pack 300ml Oil Coconut Oil 300ml 500ml 300ml Rs900 Rs1650 Rs900 Rs900 Rs800 Johnson’s Baby Johnson’s Bedtime Johnson’s Bedtime Johnson’s Bedtime Johnson’s Powder Shampoo Bath Lotion 500ml Cottontouch Oil 200g 500ml 500ml 300ml Rs950 Rs800 Rs1750 Rs1750 Rs1850 Rs1750 Johnson’s Johnson’s Johnson's No More Johnson's No More Johnson’s No More Cottontouch 2in1 Cottontouch Face & Tangles Kids Tangles Kids Tangle Kids Bath & Body Shampoo Conditioner Conditioner Spray Wash Lotion 500ml 500ml 200ml 500ml 500ml Rs1750 Rs1750 Rs1850 Rs1750 Rs1350 -

Corporate Banking Tariff 2014 - Updated 19NOV14

Corporate Banking Tariff 2014 - Updated 19NOV14 Tariff 2014 Corporate Banking This document lists the charges applicable to corporate banking transactions and services offered by the domestic branches of The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited (“HSBC”) in Mauritius as from 01st January 2014. All rates, commissions and charges in this document are subject to change, under advice to customers. Issued by The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited Current Account Monthly fee A monthly fee of Rs300+VAT will be applied if the average monthly credit balance falls below - Rs100,000 No service charge will be applied on current accounts with an overdraft facility. Activity fee An activity fee of Rs10 will be applied on counter cash withdrawals and cash / cheque deposits if: (1) the monthly total of the above transactions exceeds 5 per month and (2) the average monthly credit balance falls below Rs 100,000. Cheque-book: - 50 leaves Rs200 - 100 leaves Rs400 Cheque returned outward Rs250 Cheque returned inward Rs25 Special clearing at Port Louis Branch only (cheque of Rs200,000 and above) Rs200 Stop payment instruction Rs125 . Call Account 1. Minimum opening balance: Rs25,000 2. Interest is calculated on the daily closing balance as from Rs25,000 and is credited to the account half yearly in June and December. 3. Check the latest interest rate available at any HSBC branch. Term Deposit 1. Minimum balance Rs100,000 2. Check the latest interest rates and deposit periods available at any HSBC branch. 3. Premature withdrawal of term deposit: • Penalty will be applied based on cost incurred by the Bank in making up for the shortfall in funds. -

With Triaminic DM Based Therapies for Common

Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2017; 6(1): 258-270 E-ISSN: 2278-4136 P-ISSN: 2349-8234 JPP 2017; 6(1): 258-270 Pharmacoeconomic evaluations and comparison of Received: 05-11-2016 Accepted: 06-12-2016 licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.) with triaminic DM Syed Muzzammil Ahmad based therapies for common cold in the city of Karachi: Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy and Retrospective burden of Illness, Cost and budget Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Karachi, Karachi- impact analysis 75270, Pakistan Iqbal Azhar Professor of Pharmacognosy and Syed Muzzammil Ahmad, Iqbal Azhar, Nadia Ahmad and Syeda Dean, Faculty of Pharmacy and Darakhshan Masroor Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Karachi, Karachi- 75270, Pakistan Abstract Objective: To compare two therapeutic entity from societal perspective, i.e. ‘Licorice’ with ‘Triaminic Nadia Ahmad DM’ in monetary savings and reduction of burden of cold with minimum impact on household budget of Department of Pharmaceutics, patient in population of all 178 union councils of City of Karachi, Pakistan. Faculty of Pharmacy and Methods: Stratified random sampling was used, selecting total of 356 patients. Taking frequency of Pharmaceutical Sciences, common cold at 3 colds annually with discount rate at 3% for calculating burden of illness in terms of University of Karachi, Karachi- disability adjusted life years. The budget impact analysis was carried out calculating budget impact per 75270, Pakistan onset and budget impact per year values. Syeda Darakhshan Masroor Results: Annually, the Licorice was found responsible for 57.07 less DALY per 1000 population with a Department of Pharmacognosy, saving of Rs.1.51/- billion (US$ 14.52/- million) than with Triaminic DM.