Toponyms and Language History – Some Methodological Challenges Inge Særheim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norges Sivile, Geistlige Og Rettslige Inndeling 1 Juli 1941

Norges Offisielle Statistikk, rekke IX og X. (Statistique Officielle de la Norvège, série IX et X.) I. rt . Nr. 154. Syketrygden 1937. (Assurance-maladie nationale.) - 155. Norges jernbaner 1937-38. (Chemins de fer norvégiens.) - 156. Skolevesenets tilstand 1935-36. (Instruction publique.) - 157. Norges industri 1937. (Statistique industrielle de la Norvège.) 158. Bedriftstellingen 9. oktober 1936. Forste hefte. Detaljerte oppgaver for de enkelte næringsgrupper. (Recensement d'établissements au 9 octobre 1936. 1. Données détaillées sur les differentes branches d'activité économique.) 159. Jordbruksstatistikk 1938. (Superficies agricoles et élevage du bétail. Récoltes etc.) - 160. Sjomannstrygden 1936. Fiskertrygden 1936. (Assurances de l'État contre les accidents des marins. Assurances de l'Étal contre les accidents des marins pécheurs ) - 161. Telegrafverket 1937-38. (Télégraphes el téléphones de l'Étal.) - 162. Fagskolestatistikk 1935/36-1937/38. (Écoles professionnelles.) 163. Norges postverk 1938. (Statistique postale.) 164. Bedriftstellingen 9. oktober 1936. Annet hefte. Fylker, herreder, byer og enkelte industristrok. Særoppgaver om hotelier, biltrafikk, skipsfart. (Recense- ment d'établissements. II. Les établissements dans les dilférents districts du Royaume. Données spéciales sur hôtels, automobiles et navigation.) - 165. Skattestatistikken 1938/39. (Ripartition d'impôts.) - 166. Sinnssykeasylenes virksomhet 1937. (Statistique des hospices d'aliénés.) 167. Det sivile veterinærvesen 1937. (Service véterinaire civil.) - 168. Industriarbeidertrygden 1936. (Assurances de l'État contre les accidents pour les travailleurs de l'industrie etc.) - 169. Forbruket av trevirke på gårdene 1936/37. (Consommation de bois stir les fermes 1936137.) 170. Arbeidstiden m. v. i jordbruk og gartneri 1939. (Durée du travail etc. dans l'agriculture el les entreprises horticoles.) - 171. Folkemengdens bevegelse 1937. (Mouvement de la population.) 172. -

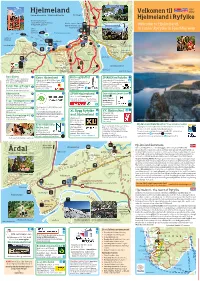

Hjelmeland 2021

Burmavegen 2021 Hjelmeland Nordbygda Velkomen til 2022 Kommunesenter / Municipal Centre Nordbygda Leite- Hjelmeland i Ryfylke Nesvik/Sand/Gullingen runden Gamle Hjelmelandsvågen Sauda/Røldal/Odda (Trolltunga) Verdas største Jærstol Haugesund/Bergen/Oslo Welcome to Hjelmeland, Bibliotek/informasjon/ Sæbø internet & turkart 1 Ombo/ in scenic Ryfylke in Fjord Norway Verdas største Jærstol Judaberg/ 25 Bygdamuseet Stavanger Våga-V Spinneriet Hjelmelandsvågen vegen 13 Sæbøvegen Judaberg/ P Stavanger Prestøyra P Hjelmen Puntsnes Sandetorjå r 8 9 e 11 s ta 4 3 g Hagalid/ Sandebukta Vågavegen a Hagalidvegen Sandbergvika 12 r 13 d 2 Skomakarnibbå 5 s Puntsnes 10 P 7 m a r k 6 a Vormedalen/ Haga- haugen Prestagarden Litle- Krofjellet Ritlandskrateret Vormedalsvegen Nasjonal turistveg Ryfylke Breidablikk hjelmen Sæbøhedlå 14 Hjelmen 15 Klungen TuntlandsvegenT 13 P Ramsbu Steinslandsvatnet Årdal/Tau/ Skule/Idrettsplass Hjelmen Sandsåsen rundt Liarneset Preikestolen Søre Puntsnes Røgelstad Røgelstadvegen KART: ELLEN JEPSON Stavanger Apal Sideri 1 Extra Hjelmeland 7 Kniv og Gaffel 10 SMAKEN av Ryfylke 13 Sæbøvegen 35, 4130 Hjelmeland Vågavegen 2, 4130 Hjelmeland Tlf 916 39 619 Vågavegen 44, 4130 Hjelmeland Tlf 454 32 941. www.apalsideri.no [email protected] Prisbelønna sider, eplemost Tlf 51 75 30 60. www.Coop.no/Extra Tlf 938 04 183. www.smakenavryfylke.no www.knivoggaffelas.no [email protected] Alt i daglegvarer – Catering – påsmurt/ Tango Hår og Terapi 2 post-i-butikk. Grocery Restaurant - Catering lunsj – selskapsmat. - Selskap. Sharing is Caring. 4130 Hjelmeland. Tlf 905 71 332 store – post office Pop up-kafé Hairdresser, beauty & personal care Hårsveisen 3 8 SPAR Hjelmeland 11 Den originale Jærstolen 14 c Sandetorjå, 4130 Hjelmeland Tlf 51 75 04 11. -

Sports Manager

Stavanger Svømme Club and Madla Svømmeklubb were merged into one swimming club on the 18th of April 2018. The new club, now called Stavanger Svømmeklubb, is today Norway's largest swimming club with 4000 members. The club that was first founded in 1910 has a long and proud history of strong traditions, defined values and solid economy. We are among the best clubs in Norway with participants in international championships (Olympics, World and European Championships). The club give children, youngsters, adults and people with disabilities the opportunity to learn, train, compete and develop in a safe, healthy and inclusive environment. The club has a general manager, an office administrator, a swimming school manager, 7 full-time coaches, as well as a number of group trainers and swimming instructors. The main goal for Stavanger Svømmeklubb is that we want be the preferred swimming club in Rogaland County and a swimming club where the best swimmers want to be. Norway's largest swimming club is seeking a Sports Manager Stavanger Svømmeklubb is seeking an experienced, competent and committed sports manager for a full time position that can broaden, develop and strengthen the club's position as one of the best swimming clubs in Norway. The club's sports manager will be responsible for coordinating, leading and implementing the sporting activity of the club, as well as having the professional responsibility and follow-up of the club's coaches. The sports manager should have knowledge of Norwegian swimming in terms of structure, culture and training philosophy. The job involves close cooperation with other members of the sports committee, general manager and coaches to develop the club. -

Bicycle Trips in Sunnhordland

ENGLISH Bicycle trips in Sunnhordland visitsunnhordland.no 2 The Barony Rosendal, Kvinnherad Cycling in SunnhordlandE16 E39 Trondheim Hardanger Cascading waterfalls, flocks of sheep along the Kvanndal roadside and the smell of the sea. Experiences are Utne closer and more intense from the seat of a bike. Enjoy Samnanger 7 Bergen Norheimsund Kinsarvik local home-made food and drink en route, as cycling certainly uses up a lot of energy! Imagine returning Tørvikbygd E39 Jondal 550 from a holiday in better shape than when you left. It’s 48 a great feeling! Hatvik 49 Venjaneset Fusa 13 Sunnhordland is a region of contrast and variety. Halhjem You can experience islands and skerries one day Hufthamar Varaldsøy Sundal 48 and fjords and mountains the next. Several cycling AUSTE VOLL Gjermundshavn Odda 546 Våge Årsnes routes have been developed in Sunnhordland. Some n Husavik e T YS NES d Løfallstrand Bekkjarvik or Folgefonna of the cycling routes have been broken down into rfj ge 13 Sandvikvåg 49 an Rosendal rd appropriate daily stages, with pleasant breaks on an a H FITJ A R E39 K VINNHER A D express boat or ferry and lots of great experiences Hodnanes Jektavik E134 545 SUNNHORDLAND along the way. Nordhuglo Rubbestad- Sunde Oslo neset S TO R D Ranavik In Austevoll, Bømlo, Etne, Fitjar, Kvinnherad, Stord, Svortland Utåker Leirvik Halsnøy Matre E T N E Sveio and Tysnes, you can choose between long or Skjershlm. B ØMLO Sydnes 48 Moster- Fjellberg Skånevik short day trips. These trips start and end in the same hamn E134 place, so you don’t have to bring your luggage. -

Innhold Flatskjæra, Terneskjæra

Vedlegg 1 - Friluftslivsområdene Innhold Flatskjæra, Terneskjæra ................................................................................................. 5 Kjeholmen – Lyngør fyr ................................................................................................... 5 Ytre Lyngør og Speken .................................................................................................... 5 Nautholmene ............................................................................................................... 7 Klåholmen, Håholmene og Kvernskjær ................................................................................ 8 Sandskjæra ................................................................................................................. 8 Risøya ........................................................................................................................ 8 Generelle trekk, Tvedestrand: .......................................................................................... 8 Klåholmen, Måkeskjær, Buskjæra ...................................................................................... 9 Vestre Kvaknes og Jonsvika .............................................................................................. 9 Gjerdalen .................................................................................................................. 10 Kalvøya og Teistholmen ................................................................................................. 10 Alvekilen .................................................................................................................. -

Kyrkjeblad for Hjelmeland, Fister, Årdal, Strand, Jørpeland Og Forsand Sokn Nr.4, Oktober 2020

Preikestolen Preikestolen Preikestolen Preikestolen KYRKJEBLAD FOR HJELMELAND, FISTER, ÅRDAL, STRAND, JØRPELAND OG FORSAND SOKN NR.4, OKTOBER 2020. 81. ÅRG. Preikestolen for å oppsøkje stader med mange folk? Engstelse, glede, sorg, sinne, Preikestolen Korleis skal me få påfyll i denne takknemlegheit. Han tek imot og Innhald nr. 4-2020: annleis - hausten? Det kan kjennast rommar det. tungt at ting er annleis. Kanskje er det Skund deg og kom ned, sa Jesus til Adresse: fleire spørsmål enn svar? Sakkeus. For i dag vil eg ta inn i ditt Postboks 188 Å forma det heilage................................................................... Side 4 Om me er heime eller ute, så ynskjer hus. Skund deg og kom, seier Jesus til 4126 Jørpeland Altertavla i Forsand kyrkje....................................................... Side 7 Gud å kome oss i møte i livet slik det oss. I dag vil eg ta inn i ditt hus. Sorg og tap................................................................................. Side 8 Neste nummer av Det gode er, ikkje slik det «burde» vere. Preikestolen kjem Ung sorg..................................................................................... Side 10 i postkassen Å dele tro og liv på tvers av generasjoner.............................. Side 12 ca. 01. Pdesember.reikestolen møte Frist for innlevering av Turist-åpen kirke........................................................................ Side 14 stoff er 30. oktober. Et minne fra Badger Iowa......................................................... Side 15 Kyrke i korona-tid..................................................................... -

Austre Moland Historielag Arkivoversikt 27.10.2020 Side 1

Austre Moland Historielag Arkivoversikt 27.10.2020 Arkiv- Indeks Objekt Antall Kategori Tema Forfatter Utgitt År Utgiver nøkkel 1 Skogen i Aust-Agder 1 Bøker Skog Vevstad Andreas 1995 1-B2 2 Austre Molands Skogeierlag 1903-1963 2 Bøker Skog 1963 1-B2 3 Austre Molands Skogeierlag 1963-1978 1 Bøker Skog 1978 1-B2 4 Austre Molands Skogeierlag 1903-2003 1 Bøker Skog 2006 1-B2 5 Østre NedenesTømmermåling 1952-53 1 Årsberetning 1953 1-B2 6 Familien Myhren - en slektshistorie 2 Bøker Slektshistorie Knudsen Inger Marie 1977 1-B2 7 Spøkefugl og alvorsmann 1 Bøker Bjorvatn Øyvind 2011 1-B2 8 Agder Historie 1840-1920 1 Bøker Slettan Bjørn 1998 1-B2 9 Den glemte arme' 1 Bøker Johansson Anders 2007 1-B2 10 Den glemte arme' 2 Bøker Johansson Anders 2011 1-B2 11 Den glømda arme'en 1939-1945 3 Bøkerøker Johansson Anders 2005 1-B2 12 P.M.Damielsen 1895-1995 1 Jubileumsbok Frøstrup/Vigerstøl 1995 1-B2 13 Kirken i Austre Moland 3 Bøker Kirke Weierholt Olav 1973 1-B2 14 Åmli Kyrkje 1 Bøker Kirke 2009 1-B2 15 Alf - et krigsbarn som holdt fast ved håpet 1 Bøker Sødal Kirsten 2007 1-B2 16 Kvinner på barrikadene 1 Bøker Haugen Johnny 2013 Agder Historielag 1-B2 17 Motorsaga - Stell og vedlikehold 1 Bøker Skog 2006 1-B2 18 Ungskogpleie 1 Bøker Skog 2007 1-B2 19 Hogst 1 Bøker Skog 2006 1-B2 20 Fotoalbum fra Nesheim barnehage 4 Bilder Barn 1-B3 21 Bøker fra Brekke skole Ukjent Bøker Skole 1-B2 22 I sol og regn på slitne bein Utvalgte dikt og noveller 13 Bøker Lawson Henry 1-B2 23 Norsk Skyttertidene 1909 1 Skytterlag 1909 Utlån Austre Moland Skytterlag 24 Norsk -

Rennesøy Finnøy Bokn Utsira Karmøy Tysvær Haugesund Vindafjord

227227 ValevValevåg Breiborg 336 239239 Ekkje HellandsbygHellandsbygd 236236 Hellandsbygda Utbjoa SaudaSauda 335 Etne Sauda Bratland 226226 Espeland VihovdaVihovda Åbødalen Brekke Sandvikdal Roaldkvam 240240 241241 Kastfosskrys 334 Egne Hjem UtbjoaUtbjoa Saunes 236 Skartland sør EtneEtne en TTråsavikikaaNærsonersone set 225225 Saua Førderde Gard Kvame Berge vest Ølen kirke Ølen Ørland Hytlingetong Gjerdevik ø EiodalenØlen skule den 332 SveioSveio 222222 Ølensvåg 235235 333 st Hamrabø Bråtveit Saudafjor 237237 224224 Øvrevre VatsVats SvandalSvandal MaldalMaldal 223223 Vindafjord SandeidSandeid Ulvevne Øvre Vats Skole Bjordalsveien Sandeid Fjellgardsvatnet Hylen Landa Løland Tengesdal 223 331 Knapphus Hordaland Østbø Hylen Blikrabygd 238238 Sandvik VanvikVanvik 328328 Vindafjord Hylsfjorden Skrunes SuldalseidSuldalseid Skjold 216216 218218 Sandeidfjorden 230230 Suldal NordreNordre VikseVikse Ørnes 228228 RopeidRopeid Isvik SkjoldSkjold Hustoft VikedalVikedal 217217 Slettafjellet Nesheim Vikedal Helganes 228 330330 Vikse kryss VestreVestre Skjoldafjo Eskedalen 221221 Suldalseid SuldalsosenSuldalsosen Haugesund Stølekrossen Førland Åmsoskrysset Åmsosen IlsvIlsvåg Stole Ølmedal Kvaløy Ropeid Skipavåg Sand Suldalsosen rden 230 Byheiene 229229 Roopeid 327 327327 Stakkestad SkipevSkipevåg kryss SandSand Kariås Røvær kai Nesheim Eikanes kryss Lindum Årek 329329 camping 602 VasshusVasshus Røvær 200200 220220 Suldalsl HaugesundHaugesund ågen Haraldshaugen 205205 Kvitanes Grindefjorden NedreNedre VatsVats Vindafjorden Kvamen Haugesund Gard skole -

Kvernsteinsbrudd På Nord-Talge I Finnøy Kommune, Rogaland

Feltrapport: Kvernsteinsbrudd på Nord-Talge i Finnøy Kommune, Rogaland Forfattere: Lisbeth Prøsch-Danielsen og Tom Heldal Forsidebilde: Tomter etter uttak av håndkverner på Nord-Talge. Rapportdato: ISBN ISSN Gradering: 10.04.2012 978-82-7385-148-2 0800-3416 Åpen NGU Rapport nr.: NGU prosjektnummer.: Sider: 44 2012.020 329900 Appendix: 6 sider Nøkkelord: Steinbrudd Kvernstein Finnøy Nord-Talge Rogaland i Denne rapport inngår i en rapportserie fra forskningsprosjektet ’Millstone’, et tverrfaglig prosjekt med samarbeid mellom geologer, arkeologer, historikere, geografer og folk med kunnskap om håndverksteknikkene. Målet med prosjektet er å kaste nytt lys over kvernsteinslandskapet i Norge, og å kartlegge hvor kvernsteinene tok veien etter at de var hogd ut i steinbruddene. Prosjektets formelle tittel er ’The Norwegian Millstone Landscape’, på norsk ’Kvernsteinslandskap i Norge’. Millstone er finansiert av Norges Forskningsråd (NFR 189986/S30) og Norges geologiske undersøkelse (NGU 329900). Prosjektet koordineres av NGU, med prosjektpartnere som listet nedenfor. Rapportene er tilgjengelig digitalt som NGU-rapport på www.ngu.no. Hver rapport er fagfellevurdert av en ekstern og en intern fagperson. Koordinator: Gurli B. Meyer, Norges geologiske undersøkelse (NGU) Partnere: Vitenskapsmuseet, Seksjon for arkeologi og kulturhistorie, Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet (NTNU) Geografisk Institutt, Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet (NTNU) Institutt for arkeologi og religionsvitenskap, Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet -

ARENDAL KOMMUNE Plan, Byggesak, Utvikling Og Landbruk

ARENDAL KOMMUNE Plan, byggesak, utvikling og landbruk Statens vegvesen Region Sør Postboks 723 Stoa Dato: 10.07.2012 4808 ARENDAL Vår ref: 2012/6096 - 2 Deres ref: Arkivkode: 2/26 Saksbeh.: Ole Johnny Andreassen Tlf.: TILLATELSE TIL TILTAK Tiltakssted: Molandsveien 1066 Gnr/Bnr: 2/26 Tiltaket: Støyskjerm Tiltakshaver: Statens vegvesen Region sør Ansvarlig søker: Statens vegvesen Region sør Søknadsdokumenter: Datert: Mottatt: Søknad om tillatelse til tiltak (ett-trinns søknad) 28.06.12 04.07.12 Beskrivelse av tiltaket Søknad om dispensasjon Gjenpart og Kvittering for nabovarsling Tegninger Situasjonskart Øvrige saksdokumenter: Datert: Mottatt: E-post med bekreftelse på at grunneier og statens 28.06.12 04.07.12 vegvesen er enige om tiltaket Ansvarlig søker: I søknaden er det gjennom avkyssing opplyst at Statens vegvesen innehar sentral foretaksgodkjenning for søkerfunksjonen. Ved søk i databasen over sentralt godkjente foretak får kommunen ikke bekreftet at så er tilfelle. Av byggesaksforskriftens § 4-3 framgår imidlertid at offentlige veganlegg hvor Statens vegvesen eller fylkeskommunen er tiltakshaver kan utføres uten at reglene i plan- og bygningsloven kapitlet 22 (Godkjenning av foretak for ansvarsrett), og kapittel 23 (Ansvar i byggesaker) kommer til anvendelse. Ut fra dette vil Statens vegvesen kunne fremme søknad uten at det blir spørsmålet om foretaksgodkjenning/ansvarsrett. Søknaden kan dermed realitetsbehandles. __________________________________________________________ Side 1 av 3 Kontaktinformasjon: www.arendal.kommune.no, telefon: 37 01 30 00, telefaks: 37 01 30 13 Postadresse: Postboks 780, Stoa, 4809 Arendal, [email protected] Organisasjon: Org.nr.: 940493021/IBAN: NO3063120504241/SWIFT: NDEANOKK Bankforbindelse: Nordea, bankkontonr.: 6312 05 04241 VEDTAK: Med hjemmel i pbl § 19-2 gis det dispensasjon fra kommuneplanens arealdel for oppføring/anlegging av støyskjerm ved Klokkerud Gård Kommunen gir tillatelse for oppføring/anlegging av støyskjerm som omsøkt ved Klokkerud Gård. -

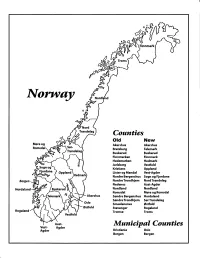

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Raet Protected Landscape

Raet Protected Landscape Arendal kommune, Aust-Agder Raet Protected Landscape There are three main criteria that form the Five methods for the protection of the area: basis for the protection of Raet Protected Raet (1) Protected Landscape, including Landscape. the flora and fauna, was protected by Royal Decree on 15 December 2000. The pro- These are: tected area stretches from, and includes, • sediments Jerkholmen in the west to Tromlingene in • geomorphology the east – a distance of about 15 kms. The • fresh water dammed up by the moraine protected area covers about 5,400 acres, of which about 4,600 acres is sea. The many bare outcrops of rock shaped by glacial erosion that we find in the area are The aim of the protection is «to preserve the examples of geomorphological shapes. specific character of the natural landscape These are bedrock bumps that have been and the cultivated land with geological ground smooth and fine on the stoss faces occurrences from the Quaternary period towards the ice and torn up on the lee faces. and distinctive animal and plant life linked with Raet in the coastal area of Aust-Agder». Front page photo from Bjellandsskjær, Tromøy. Photo: Ove Hetland Tromlingene Tromøysund Alvekilen Arendal Tromøya Bjelland Galtesund Spornes Hisøya Hove Gjesøya Merdø Havsøya Gjervolds Ærøya øya Lille Torungen Halvors holmene Store Torungen Jerkholmen 2 Within the area there are three (2) nature final spasms of the Ice Age. Probably the reserves which is a «stricter» form of pro- glacial front of the inland ice towered like a tection than protected landscapes.