Transcript of Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helsides Faksutskrift

IFS Info 6/1997 Robert G .. Patman Securing Somalia A Comparisollil of US am!! AWistll'aHcm IPeacekeepillilg oclmillilg the UIMITAf Operatiollil Note on the author .................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 5 The Disintegration of the Somali State ...................................................................................... 5 International Intervention: A Mandate to Disarm or Not to Disarm? .......................................... 7 Cosmetic Disarmament in Mogadishu ...................................................................................... 9 Active Disarmament in Baidoa ............................................................................................... 14 A Comparative Assessment . ... ... .. ... ... .. .. .... .. .. ... .. .. .. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... .. ... .. ..... .. .. .. .. .. .. ..... .. 18 I. Mission definition ............................................................................................................................. 18 2. Style of Peace Operations ................................................................................................................. 19 3. Cultural compatibility ........................................................................................................................ 20 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................... -

Of the 90 YEARS of the RAAF

90 YEARS OF THE RAAF - A SNAPSHOT HISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia, or of any other authority referred to in the text. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Release This document is approved for public release. Portions of this document may be quoted or reproduced without permission, provided a standard source credit is included. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry 90 years of the RAAF : a snapshot history / Royal Australian Air Force, Office of Air Force History ; edited by Chris Clark (RAAF Historian). 9781920800567 (pbk.) Australia. Royal Australian Air Force.--History. Air forces--Australia--History. Clark, Chris. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Office of Air Force History. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Air Power Development Centre. 358.400994 Design and layout by: Owen Gibbons DPSAUG031-11 Published and distributed by: Air Power Development Centre TCC-3, Department of Defence PO Box 7935 CANBERRA BC ACT 2610 AUSTRALIA Telephone: + 61 2 6266 1355 Facsimile: + 61 2 6266 1041 Email: [email protected] Website: www.airforce.gov.au/airpower Chief of Air Force Foreword Throughout 2011, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) has been commemorating the 90th anniversary of its establishment on 31 March 1921. -

Additional Estimates 2010-11

Dinner on the occasion of the First Meeting of the International Commission on Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament Kirribilli House, Kirribilli, Sydney Sunday, 19 October 2008 Host Mr Francois Heisbourg The Honourable Kevin Rudd MP Commissioner (France) Prime Minister Chairman of the International Institute for Strategic Studies and Geneva Centre for Official Party Security Policy, Special Adviser at the The Honourable Gareth Evans AO QC Foundation pour la Recherche Strategique Co-Chair International Commission on Nuclear Non- General (Ret'd) Jehangir Karamat proliferation and Disarmament Commissioner (Pakistan) and President of the International Crisis Director, Spearhead Research Group Mrs Nilofar Karamat Ms Yoriko Kawaguchi General ((Ret'd) Klaus Naumann Co-Chair Commissioner (Germany) International Commission on Nuclear Non- Member of the International Advisory Board proliferation and Disarmament and member of the World Security Network Foundation of the House of Councillors and Chair of the Liberal Democratic Party Research Dr William Perry Commission on the Environment Commissioner (United States) Professor of Stanford University School of Mr Ali Alatas Engineering and Institute of International Commissioner (Indonesia) Studies Adviser and Special Envoy of the President of the Republic of Indonesia Ambassador Wang Yingfan Mrs Junisa Alatas Commissioner (China) Formerly China's Vice Foreign Minister Dr Alexei Arbatov (1995-2000), China's Ambassador and Commissioner (Russia) Permanent Representative to the United Scholar-in-residence -

RAM Index As at 1 September 2021

RAM Index As at 1 September 2021. Use “Ctrl F” to search Current to Vol 74 Item Vol Page Item Vol Page This Index is set out under the Aircraft armour 65 12 following headings. Airbus A300 16 12 Airbus A340 accident 43 9 Airbus A350 37 6 Aircraft. Airbus A350-1000 56 12 Anthony Element. Airbus A400 Avalon 2013 2 Airbus Beluga 66 6 Arthur Fry Airbus KC-30A 36 12 Bases/Units. Air Cam 47 8 Biographies. Alenia C-27 39 6 All the RAAF’s aircraft – 2021 73 6 Computer Tips. ANA’s DC3 73 8 Courses. Ansett’s Caribou 8 3 DVA Issues. ARDU Mirage 59 5 Avro Ansons mid air crash 65 3 Equipment. Avro Lancaster 30 16 Gatherings. 69 16 General. Avro Vulcan 9 10 Health Issues. B B2 Spirit bomber 63 12 In Memory Of. B-24 Liberator 39 9 Jeff Pedrina’s Patter. 46 9 B-32 Dominator 65 12 John Laming. Beaufighter 61 9 Opinions. Bell P-59 38 9 Page 3 Girls. Black Hawk chopper 74 6 Bloodhound Missile 38 20 People I meet. 41 10 People, photos of. Bloodhounds at Darwin 48 3 Reunions/News. Boeing 307 11 8 Scootaville 55 16 Boeing 707 – how and why 47 10 Sick Parade. Boeing 707 lost in accident 56 5 Sporting Teams. Boeing 737 Max problems 65 16 Squadrons. Boeing 737 VIP 12 11 Boeing 737 Wedgetail 20 10 Survey results. Boeing new 777X 64 16 Videos Boeing 787 53 9 Where are they now Boeing B-29 12 6 Boeing B-52 32 15 Boeing C-17 66 9 Boeing KC-46A 65 16 Aircraft Boeing’s Phantom Eye 43 8 10 Sqn Neptune 70 3 Boeing Sea Knight (UH-46) 53 8 34 Squadron Elephant walk 69 9 Boomerang 64 14 A A2-295 goes to Scottsdale 48 6 C C-130A wing repair problems 33 11 A2-767 35 13 CAC CA-31 Trainer project 63 8 36 14 CAC Kangaroo 72 5 A2-771 to Amberley museum 32 20 Canberra A84-201 43 15 A2-1022 to Caloundra RSL 36 14 67 15 37 16 Canberra – 2 Sqn pre-flight 62 5 38 13 Canberra – engine change 62 5 39 12 Canberras firing up at Amberley 72 3 A4-208 at Oakey 8 3 Caribou A4-147 crash at Tapini 71 6 A4-233 Caribou landing on nose wheel 6 8 Caribou A4-173 accident at Ba To 71 17 A4-1022 being rebuilt 1967 71 5 Caribou A4-208 71 8 AIM-7 Sparrow missile 70 3 Page 1 of 153 RAM Index As at 1 September 2021. -

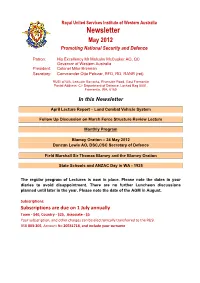

Newsletter May 2012 Promoting National Security and Defence

Royal United Services Institute of Western Australia Newsletter May 2012 Promoting National Security and Defence Patron: His Excellency Mr Malcolm McCusker AO, QC Governor of Western Australia President: Colonel Mike Brennan Secretary: Commander Otto Pelczar, RFD, RD, RANR (ret) RUSI of WA, Leeuwin Barracks, Riverside Road, East Fremantle Postal Address: C/- Department of Defence, Locked Bag 5001, Fremantle, WA, 6160 In this Newsletter April Lecture Report – Land Combat Vehicle System Follow Up Discussion on March Force Structure Review Lecture Monthly Program Blamey Oration – 24 May 2012 Duncan Lewis AO, DSC,CSC Secretary of Defence Field Marshall Sir Thomas Blamey and the Blamey Oration State Schools and ANZAC Day in WA - 1925 The regular program of Lectures is now in place. Please note the dates in your diaries to avoid disappointment. There are no further Luncheon discussions planned until later in the year. Please note the date of the AGM in August. Subscriptions: Subscriptions are due on 1 July annually Town - $40, Country - $25, Associate - $5 Your subscription, and other charges can be electronically transferred to the RUSI. BSB 803-205, Account No 20531718, and include your surname RUSI of WA Newsletter 2 May 2012 April Lecture Report – Land Combat Vehicle System Brigadier Nagy Sorial, the Director General Combined Arms Fighting System and Program Manager Land 400, Land Combat Vehicle System, delivered the April lecture. During the lecture, Brigadier Sorial outlined the intent of the Land 400 Land Combat Vehicle System (LCVS) to provide the mounted close combat capability for the Land Force as well as being the lead project for integration within the Combined Arms Fighting System (CAFS). -

IB # 366-New Text

JUNE 2020 ISSUE NO. 366 Australia-China Relations: The Great Unravelling NAVDEEP SURI ABSTRACT Over the last three decades, Australia and China have established mutually beneficial economic ties. However, Australia’s decision to ask for an independent enquiry into the origins of SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, has led to a backlash from China. This brief examines the more important developments since 2015 that persuaded Australia to take measures aimed at protecting both its open economy and its democratic polity against China’s systematic campaign to expand its influence. The brief describes various case studies including the attempts by the Chinese Communist Party to use Australia’s large Chinese community to support its foreign policy objectives, its attempts to secure strategic economic assets in Australia, and its efforts to use corrupt practices for recruiting politicians who would support its agenda. Attribution: Navdeep Suri, “Australia-China Relations: The Great Unravelling,” ORF Issue Brief No. 366, June 2020, Observer Research Foundation. Observer Research Foundation (ORF) is a public policy think tank that aims to influence the formulation of policies for building a strong and prosperous India. ORF pursues these goals by providing informed analyses and in-depth research, and organising events that serve as platforms for stimulating and productive discussions. ISBN 978-93-90159-20-8 © 2020 Observer Research Foundation. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied, archived, retained or transmitted through print, speech or electronic media without prior written approval from ORF. Australia-China Relations: The Great Unravelling INTRODUCTION reaction from China. Australia has held firm in its response to threats of economic coercion, Over the last three decades, China and causing concern in business circles about the Australia have developed a mutually new dynamics of the relationship. -

Australia's Joint Approach Past, Present and Future

Australia’s Joint Approach Past, Present and Future Joint Studies Paper Series No. 1 Tim McKenna & Tim McKay This page is intentionally blank AUSTRALIA’S JOINT APPROACH PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE by Tim McKenna & Tim McKay Foreword Welcome to Defence’s Joint Studies Paper Series, launched as we continue the strategic shift towards the Australian Defence Force (ADF) being a more integrated joint force. This series aims to broaden and deepen our ideas about joint and focus our vision through a single warfighting lens. The ADF’s activities have not existed this coherently in the joint context for quite some time. With the innovative ideas presented in these pages and those of future submissions, we are aiming to provoke debate on strategy-led and evidence-based ideas for the potent, agile and capable joint future force. The simple nature of ‘joint’—‘shared, held, or made by two or more together’—means it cannot occur in splendid isolation. We need to draw on experts and information sources both from within the Department of Defence and beyond; from Core Agencies, academia, industry and our allied partners. You are the experts within your domains; we respect that, and need your engagement to tell a full story. We encourage the submission of detailed research papers examining the elements of Australian Defence ‘jointness’—officially defined as ‘activities, operations and organisations in which elements of at least two Services participate’, and which is reliant upon support from the Australian Public Service, industry and other government agencies. This series expands on the success of the three Services, which have each published research papers that have enhanced ADF understanding and practice in the sea, land, air and space domains. -

The Establishment of the Joint Australia-United States Relay Ground Station at Pine Gap

HIDING FROM THE LIGHT: THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE JOINT AUSTRALIA-UNITED STATES RELAY GROUND STATION AT PINE GAP The NAPSNet Policy Forum provides expert analysis of contemporary peace and security issues in Northeast Asia. As always, we invite your responses to this report and hope you will take the opportunity to participate in discussion of the analysis. Recommended Citation Richard Tanter, "HIDING FROM THE LIGHT: THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE JOINT AUSTRALIA- UNITED STATES RELAY GROUND STATION AT PINE GAP", NAPSNet Policy Forum, November 02, 2019, https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-policy-forum/hiding-from-the-light-the-establis- ment-of-the-joint-australia-united-states-relay-ground-station-at-pine-gap/ RICHARD TANTER 1 NOVEMBER 2, 2019 I. INTRODUCTION In this essay, the author discusses recently released Australian cabinet papers dealing with a decision in September 1997 to allow the establishment of a Joint Australia-United States Relay Ground Station at Pine Gap to support two United States early warning satellite systems in place of its predecessor, the Joint Space Communications Facility at Nurrungar. The cabinet papers give a picture, albeit one muddied by censorship, of the Howard government’s consideration of ‘a U.S. request to continue Australian involvement in a U.S. space technological system to provide the U.S. with not only early warning of missile attack as a basis of nuclear deterrence, but also the capacity to target a retaliatory nuclear strike in the most effective way as part of a nuclear war-fighting capability. There is little evidence in these documents that senior ministers and their advisors considered these matters with any seriousness.’ The report is also published as a PDF file (1MB) here. -

Regional Development and Decentralisation Committee Inquiry

Regional Development and Decentralisation Committee Inquiry into Regional Development and Decentralisation Department of Defence Written Submission September 2017 Executive Summary 1. Defence has a significant presence in regional Australia and contributes to the socio- economic fabric of these communities. For the purpose of this submission the term ‘regional’ is defined as any area outside of the main metropolitan areas of Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide, Perth and Canberra. 2. The location of Defence personnel, bases and facilities is driven by strategic priorities underpinned by the 2016 Defence White Paper, the 2016 Defence Integrated Investment Program (IIP) and the Defence Estate Strategy. The IIP was developed through a comprehensive Force Structure Review that assessed Defence’s capability needs and priorities to determine Defence’s future presence, comprising: location, equipment, information and communications technology, infrastructure and workforce requirements. 3. Defence has an integrated workforce, including permanent Australian Defence Force (ADF) members, Reservists, Australian Public Service (APS) employees, contractors and other service providers who work together to deliver Defence capability. The quality of the workforce is the foundation of Defence’s capability, effectiveness and reputation. As at 30 June 2017, the total number of Defence personnel in regional centres across Australia was 33,300, which equates to around 34 per cent of its total workforce of 97,911. This presence has enabled Defence to develop -

ASIO Report to Parliament 2014–2015

ASIO Report to Parliament 2014–2015 www.asio.gov.au THE INTELLIGENCE EDGE VISION FOR A SECURE AUSTRALIA To identify and investigate threats to security and provide MISSION advice to protect Australia, its people and its interests EXCELLENCE VALUES Producing high-quality, relevant, timely advice. Displaying strong leadership and professionalism. Improving through innovation and learning. INTEGRITY Being ethical and working without bias. Maintaining the confidentiality and security of our work. Respecting others and valuing diversity. RESPECT We show respect in our dealings with others. ACCOUNTABILITY Being responsible for what we do and for our outcomes. Being accountable to the Australian community through the government and the parliament. COOPERATION Building a common sense of purpose and mutual support. Using appropriate communication in all our relationships. Fostering and maintaining productive partnerships. ASIO Report to Parliament 2014–2015 ISSN 0815-4562 (print) ISSN 2204-4213 (online) © Commonwealth of Australia (Australian Security Intelligence Organisation) 2015 All material presented in this publication is provided under a Creative Commons (CC) BY Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/3.0/au/deed.en). The details of the relevant licence Commonwealth Coat of Arms conditions are available on the The Commonwealth Coat of Arms is used Creative Commons website in accordance with Commonwealth Coat of (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/) Arms: information and guidelines, provided as is the full legal code for the CC BY by the Department of the Prime Minister Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence and Cabinet, dated November 2012, viewed (http://creativecommons.org/ 22 July 2014, (http://www.dpmc.gov.au/ licenses/by/3.0/legalcode). -

Archived Content Information Archivée Dans Le

Archived Content Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page. Information archivée dans le Web Information archivée dans le Web à des fins de consultation, de recherche ou de tenue de documents. Cette dernière n’a aucunement été modifiée ni mise à jour depuis sa date de mise en archive. Les pages archivées dans le Web ne sont pas assujetties aux normes qui s’appliquent aux sites Web du gouvernement du Canada. Conformément à la Politique de communication du gouvernement du Canada, vous pouvez demander de recevoir cette information dans tout autre format de rechange à la page « Contactez-nous ». CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE / COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 33 / PCEMI 33 MDS RESEARCH PROJECT/PROJET DE RECHERCHE DE LA MED Deeds and Words: An Integrated Special Operations Doctrine for the Canadian Forces By /par Maj/maj T.W. (Theo) Heuthorst This paper was written by a student La présente étude a été rédigée par un attending the Canadian Forces College in stagiaire du Collège des Forces fulfilment of one of the requirements of the canadiennes pour satisfaire à l'une des Course of Studies. The paper is a scholastic exigences du cours. L'étude est un document, and thus contains facts and document qui se rapporte au cours et opinions, which the author alone considered contient donc des faits et des opinions que appropriate and correct for the subject. -

6. Australia's China Debate in 2018

AUSTRALIA’S CHINA DEBATE IN 2018 David Brophy Sydney’s Chinatown Source: Paul Carmona, Flickr FOR SOME TIME NOW, Australia’s foreign policy establishment has contemplated how best to navigate the rivalry between the US and China, and debated whether or not Australia would one day have to choose between the two. Participants in this ‘old’ China debate might have disagreed on the timeline of China’s rise, or the likelihood of serious conflict between our defence partner and our trading partner, but there was a degree of consensus as to the parameters of the question. By the end of 2017, though, a string of highly visible imbroglios had seen a ‘new’ China debate take centre stage: one side arguing that there was widespread Chinese Party-state interference in Australian affairs; the other accusing the first of sensationalism, even racism. Throughout 2018, some of the basic facts about China’s presence in, and intentions towards, Australia seemed up for grabs. The ‘China question’ had become a much more polarised, and polarising one. In this new landscape, conventional political lines have tended to blur. 156 Hawkish narratives of Chinese expansionism occasionally draw support 157 from those whose primary concern is with the parlous state of human rights in China. Those anxious to prevent a resurgence of anti-Chinese xenophobia sometimes find themselves taking the same side of a point as corporate actors, whose priority is to moderate criticism of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and get on with profiting from its vast economy. The government’s attack on (now retired) Australian Labor Party (ALP) senator Sam Dastyari in 2017 (see the China Story Yearbook 2016: Control, Chapter 8 ‘Making the World Safe (For China)’, pp.278–293) set a new prec- Australia’s China Debate in 2018 Australia’s David Brophy edent in the instrumentalisation of China anxieties for domestic political gain.