6. Australia's China Debate in 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Misconduct: the Case for a Federal Icac

MISCONDUCT IN POLITICS A HISTORY OF MISCONDUCT: THE CASE FOR A FEDERAL ICAC INDEPENDENT JO URNALISTS MICH AEL WES T A ND CALLUM F OOTE, COMMISSIONED B Y G ETUP 1 MISCONDUCT IN POLITICS MISCONDUCT IN RESOURCES, WATER AND LAND MANAGEMENT Page 5 MISCONDUCT RELATED TO UNDISCLOSED CONFLICTS OF INTEREST Page 8 POTENTIAL MISCONDUCT IN LOBBYING MISCONDUCT ACTIVITIES RELATED TO Page 11 INAPPROPRIATE USE OF TRANSPORT Page 13 POLITICAL DONATION SCANDALS Page 14 FOREIGN INFLUENCE ON THE POLITICAL PROCESS Page 16 ALLEGEDLY FRAUDULENT PRACTICES Page 17 CURRENT CORRUPTION WATCHDOG PROPOSALS Page 20 2 MISCONDUCT IN POLITICS FOREWORD: Trust in government has never been so low. This crisis in public confidence is driven by the widespread perception that politics is corrupt and politicians and public servants have failed to be held accountable. This report identifies the political scandals of the and other misuse of public money involving last six years and the failure of our elected leaders government grants. At the direction of a minister, to properly investigate this misconduct. public money was targeted at voters in marginal electorates just before a Federal Election, In 1984, customs officers discovered a teddy bear potentially affecting the course of government in in the luggage of Federal Government minister Australia. Mick Young and his wife. It had not been declared on the Minister’s customs declaration. Young This cheating on an industrial scale reflects a stepped aside as a minister while an investigation political culture which is evolving dangerously. into the “Paddington Bear Affair” took place. The weapons of the state are deployed against journalists reporting on politics, and whistleblowers That was during the prime ministership of Bob in the public service - while at the same time we Hawke. -

Understanding and Combating Russian and Chinese Influence Operations by Carolyn Kenney, Max Bergmann, and James Lamond February 28, 2019

Understanding and Combating Russian and Chinese Influence Operations By Carolyn Kenney, Max Bergmann, and James Lamond February 28, 2019 Russia’s interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential elections has focused American attention on the long-standing and complicated subject of malign foreign influence operations. While Russia has brought this issue into the mainstream political conversa- tion, concerns over the ability of foreign nations—particularly autocracies—to exploit the openness of America’s democracy in order to influence U.S. policy and politics are not confined to any single foreign actor. In fact, influence efforts by Iran and Persian Gulf monarchies have also drawn considerable scrutiny, as have those carried out by China.1 Yet when considering offenders’ capabilities and positions as geopolitical com- petitors, China and Russia stand out as the two most immediate concerns. While foreign influence operations are not new, the convergence of three larger global trends has made them a more important and acute challenge. The first trend is the re-emergence of geopolitical great power competition, which is why the United States’ renewed attention on foreign influence should focus primarily on the country’s great- est geopolitical adversaries—Russia and China.2 However, Russia and China are also bolstered geopolitically by the second trend: the rise of nationalism and authoritarian- ism around the world, particularly in democracies, which is a driving force behind the unfortunate return of great power competition. Authoritarian regimes have seized on a series of setbacks within liberal democracies to bolster the image of alternative autocratic models of political and economic governance on a global scale.3 In addition, auto- cratic regimes have exploited the openness of liberal democratic societies to influence and undermine democracy. -

Testimony Before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission

Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Five Years Later Regional Reactions and Competing Visions 25 January 2018 Tobias Harris Vice President, Teneo Intelligence Economy, Trade, and Business Fellow, Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA Introduction Thank you for giving me the opportunity to testify before the U.S.-China Economic Security Review Commission today on the subject of regional reactions to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China’s USD 1tn program of infrastructure investment presents opportunities for its sixty-five member countries to develop, while also raising risks of over-dependence on Chinese investment, unsustainable borrowing, and high environmental and social costs for host nations.1 The risks and opportunities of the BRI extend even to Asia’s developed democracies, which already have complex economic relationships with China and interests in promoting development across Asia. In my remarks today I will focus on how Japan – which is in the process of developing a strategy of limited engagement with the BRI – has responded to the BRI, touching briefly on Australia to show some of the difficulties presented by the BRI. The Japanese case is particularly instructive because it shows that on the one hand, building a positive relationship with China may increasingly require engagement with the BRI in some form, while, on the other hand, showing that it is possible and even necessary for Asia’s wealthier democracies to pursue their own development strategies to help BRI members minimize their dependence on China and maximize their freedom of action. Japan may not be able to match China’s promises dollar for dollar, but through its willingness to increase its lending, loosen rules and implement other reforms to its foreign assistance institutions, and to promote private investment by Japanese companies Tokyo has arguably outlined a possible response to the BRI even as it considers participating in the BRI. -

Still Anti-Asian? Anti-Chinese? One Nation Policies on Asian Immigration and Multiculturalism

Still Anti-Asian? Anti-Chinese? One Nation policies on Asian immigration and multiculturalism 仍然反亚裔?反华裔? 一国党针对亚裔移民和多元文化 的政策 Is Pauline Hanson’s One Nation party anti-Asian? Just how much has One Nation changed since Pauline Hanson first sat in the Australian Parliament two decades ago? This report reviews One Nation’s statements of the 1990s and the current policies of the party. It concludes that One Nation’s broad policies on immigration and multiculturalism remain essentially unchanged. Anti-Asian sentiments remain at One Nation’s core. Continuity in One Nation policy is reinforced by the party’s connections with anti-Asian immigration campaigners from the extreme right of Australian politics. Anti-Chinese thinking is a persistent sub-text in One Nation’s thinking and policy positions. The possibility that One Nation will in the future turn its attacks on Australia's Chinese communities cannot be dismissed. 宝林·韩森的一国党是否反亚裔?自从宝林·韩森二十年前首次当选澳大利亚 议会议员以来,一国党改变了多少? 本报告回顾了一国党在二十世纪九十年代的声明以及该党的现行政策。报告 得出的结论显示,一国党关于移民和多元文化的广泛政策基本保持不变。反 亚裔情绪仍然居于一国党的核心。通过与来自澳大利亚极右翼政坛的反亚裔 移民竞选人的联系,一国党的政策连续性得以加强。反华裔思想是一国党思 想和政策立场的一个持久不变的潜台词。无法排除一国党未来攻击澳大利亚 华人社区的可能性。 Report Philip Dorling May 2017 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned research. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, social and environmental issues. OUR PHILOSOPHY As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. -

Additional Estimates 2010-11

Dinner on the occasion of the First Meeting of the International Commission on Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament Kirribilli House, Kirribilli, Sydney Sunday, 19 October 2008 Host Mr Francois Heisbourg The Honourable Kevin Rudd MP Commissioner (France) Prime Minister Chairman of the International Institute for Strategic Studies and Geneva Centre for Official Party Security Policy, Special Adviser at the The Honourable Gareth Evans AO QC Foundation pour la Recherche Strategique Co-Chair International Commission on Nuclear Non- General (Ret'd) Jehangir Karamat proliferation and Disarmament Commissioner (Pakistan) and President of the International Crisis Director, Spearhead Research Group Mrs Nilofar Karamat Ms Yoriko Kawaguchi General ((Ret'd) Klaus Naumann Co-Chair Commissioner (Germany) International Commission on Nuclear Non- Member of the International Advisory Board proliferation and Disarmament and member of the World Security Network Foundation of the House of Councillors and Chair of the Liberal Democratic Party Research Dr William Perry Commission on the Environment Commissioner (United States) Professor of Stanford University School of Mr Ali Alatas Engineering and Institute of International Commissioner (Indonesia) Studies Adviser and Special Envoy of the President of the Republic of Indonesia Ambassador Wang Yingfan Mrs Junisa Alatas Commissioner (China) Formerly China's Vice Foreign Minister Dr Alexei Arbatov (1995-2000), China's Ambassador and Commissioner (Russia) Permanent Representative to the United Scholar-in-residence -

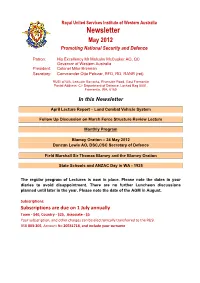

Newsletter May 2012 Promoting National Security and Defence

Royal United Services Institute of Western Australia Newsletter May 2012 Promoting National Security and Defence Patron: His Excellency Mr Malcolm McCusker AO, QC Governor of Western Australia President: Colonel Mike Brennan Secretary: Commander Otto Pelczar, RFD, RD, RANR (ret) RUSI of WA, Leeuwin Barracks, Riverside Road, East Fremantle Postal Address: C/- Department of Defence, Locked Bag 5001, Fremantle, WA, 6160 In this Newsletter April Lecture Report – Land Combat Vehicle System Follow Up Discussion on March Force Structure Review Lecture Monthly Program Blamey Oration – 24 May 2012 Duncan Lewis AO, DSC,CSC Secretary of Defence Field Marshall Sir Thomas Blamey and the Blamey Oration State Schools and ANZAC Day in WA - 1925 The regular program of Lectures is now in place. Please note the dates in your diaries to avoid disappointment. There are no further Luncheon discussions planned until later in the year. Please note the date of the AGM in August. Subscriptions: Subscriptions are due on 1 July annually Town - $40, Country - $25, Associate - $5 Your subscription, and other charges can be electronically transferred to the RUSI. BSB 803-205, Account No 20531718, and include your surname RUSI of WA Newsletter 2 May 2012 April Lecture Report – Land Combat Vehicle System Brigadier Nagy Sorial, the Director General Combined Arms Fighting System and Program Manager Land 400, Land Combat Vehicle System, delivered the April lecture. During the lecture, Brigadier Sorial outlined the intent of the Land 400 Land Combat Vehicle System (LCVS) to provide the mounted close combat capability for the Land Force as well as being the lead project for integration within the Combined Arms Fighting System (CAFS). -

Karvelas – Transcript

THE HON RICHARD MARLES MP SHADOW MINISTER FOR DEFENCE MEMBER FOR CORIO E&OE TRANSCRIPT SKY NEWS LIVE KARVELAS SUNDAY, 17 DECEMBER 2017 SUBJECTS: Bennelong; citizenship; China HOST: I'm joined now by the Shadow Defence Minister, Richard Marles, who's been listening in. Welcome to the program. RICHARD MARLES, SHADOW MINISTER FOR DEFENCE: Good evening, Patricia. How are you? HOST: Good. So, obviously very different spin on the Bennelong result from both sides of politics. I'm not really surprised by that. But what I really want to quiz you on is that in the last part of the campaign Labor really ramped up this argument in the last days that the Government was anti-Chinese. Was that the wrong thing to say in hindsight? MARLES: Well I think the issue that we were raising was that the Government completely overreached in the way in which it was dealing with Sam Dastyari. You know, when we were hearing comments such as being a double agent, such as treason, there was a question that was asked in the last week of Parliament which essentially accused China of being an enemy, I mean all of that is overreach and it was done for political purposes in the context of Bennelong. The point really, here, is that we're talking about - when we're dealing with China, the US, East Asia, our sphere of influence, all that's going on there - very difficult and sensitive topics and we need to be adults about it and actually it does need to be above politics and we need to be thoughtful and it got completely caught up in the politics of the moment and I think that was very concerning. -

The Great Australian China Debate: Implications for the United States and the World

The Great Australian China Debate: Implications for the United States and the World Professor Rory Medcalf Head, National Security College Australian National University Remarks delivered at the Sigur Center for Asian Studies George Washington University Washington DC Monday September 10 2018 Politics here in the United States has become somewhat too interesting of late, but unfortunately Australia in its own ways is becoming interesting too. The situation on which I will reflect – the changing Australia-China relationship, especially on questions of geopolitics and foreign interference – is of course about much more than Australia and its own kind of political difficulties. The Australian experience offers useful insights for a set of security and foreign policy problems shared by many countries in our Indo-Pacific region and globally. How do we manage Chinese power and assertiveness in ways that lead neither to conflict nor capitulation? How do we protect democratic institutions from foreign interference and influence – whether from the PRC or another power – in ways consistent with both national interests and national values, such as civil liberties, non-discrimination and an inclusive society? And how do we distinguish different kinds of foreign involvement – how is, say, criminal interference distinct from mere influence, and how in response do we fashion and deploy suitable instruments of policy? To understand all this, an important clue lies in a key line from the speech former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull used to introduce the nation’s legislative response last December. “… our rejection of covert, coercive or corrupting behaviour leads naturally to a counter-foreign-interference strategy that is built upon the four pillars of sunlight, enforcement, deterrence and capability.” 1 It’s a rich sentence, both conceptual and practical, worth unpacking and useful for any country considering analogous problems. -

Economics References Committee

The Senate Economics References Committee Corporate tax avoidance Part III Much heat, little light so far May 2018 © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 ISBN 978-1-76010-772-7 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/ Printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Parliament House, Canberra. ii Senate Economics References Committee Members in the 45th Parliament Senator Chris Ketter (Chair) Queensland, ALP Senator Jane Hume (Deputy Chair) Victoria, LP Senator Cory Bernardi South Australia, IND (to 12 September 2016 and from 5 December 2016 to 15 February 2017) Senator Sam Dastyari (to 5 February 2018) New South Wales, ALP Senator the Hon Kristina Keneally (from 15 February 2018) New South Wales, ALP Senator the Hon Ian Macdonald Queensland, LP (from 12 September 2016 to 5 December 2017 and from 15 February 2017 to 22 March 2018) Senator Jenny McAllister New South Wales, ALP Senator Amanda Stoker (from 22 March 2018) Queensland, LP Senator Peter Whish-Wilson (from 14 November 2017) Tasmania, AG Senator Nick Xenophon (to 31 October 2017) South Australia, NXT Senators participating in this inquiry in the 45th Parliament Senator the Hon Doug Cameron New South Wales, ALP Senator Kimberley Kitching Victoria, ALP Senator Gavin Marshall Victoria, ALP Senator Glenn Sterle Western Australia, ALP Senator Dean Smith Western Australia, LP Members in the 44th Parliament Senator Chris Ketter (Chair from 22 October 2015) Queensland, ALP Senator Sean Edwards (Deputy Chair) South Australia, LP Senator Matthew Canavan (to 23 February 2016) Queensland, NATS Senator Sam Dastyari (Chair until 22 October 2015) New South Wales, ALP Senator the Hon. -

IB # 366-New Text

JUNE 2020 ISSUE NO. 366 Australia-China Relations: The Great Unravelling NAVDEEP SURI ABSTRACT Over the last three decades, Australia and China have established mutually beneficial economic ties. However, Australia’s decision to ask for an independent enquiry into the origins of SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, has led to a backlash from China. This brief examines the more important developments since 2015 that persuaded Australia to take measures aimed at protecting both its open economy and its democratic polity against China’s systematic campaign to expand its influence. The brief describes various case studies including the attempts by the Chinese Communist Party to use Australia’s large Chinese community to support its foreign policy objectives, its attempts to secure strategic economic assets in Australia, and its efforts to use corrupt practices for recruiting politicians who would support its agenda. Attribution: Navdeep Suri, “Australia-China Relations: The Great Unravelling,” ORF Issue Brief No. 366, June 2020, Observer Research Foundation. Observer Research Foundation (ORF) is a public policy think tank that aims to influence the formulation of policies for building a strong and prosperous India. ORF pursues these goals by providing informed analyses and in-depth research, and organising events that serve as platforms for stimulating and productive discussions. ISBN 978-93-90159-20-8 © 2020 Observer Research Foundation. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied, archived, retained or transmitted through print, speech or electronic media without prior written approval from ORF. Australia-China Relations: The Great Unravelling INTRODUCTION reaction from China. Australia has held firm in its response to threats of economic coercion, Over the last three decades, China and causing concern in business circles about the Australia have developed a mutually new dynamics of the relationship. -

Australian Story – Monday 31 July, 8Pm on ABC and ABC Iview

RELEASED: Wednesday 26 July, 2017 Australian Story – Monday 31 July, 8pm on ABC and ABC iview Playing With Fire Bill Shorten ripped me a new one. Senator Sam Dastyari You can’t just think that you live in a business without consequences. Opposition Leader Bill Shorten Labor Senator Sam Dastyari speaks exclusively to Australian Story to confront head-on the political donations scandal that cost him his seat on the Opposition frontbench last year. Senator Dastyari was a rising star in the corridors of Parliament House, and on social media, until it was revealed he’d allowed a business with links to the Chinese government to pay a travel bill for his office. When a day later it was revealed that he had contradicted ALP policy on the South China Sea, at a press conference he had given alongside a major Chinese donor, his career imploded. The outcome of that press conference was because of my own actions and my own mistake and I resigned to take responsibility and pay the price. Senator Sam Dastyari This Australian Story features interviews with Sam Dastyari, his family and politicians on all sides. It traces the colourful 34-year-old’s life from his arrival in Australia as a four-year-old, after fleeing the religious regime in Iran with his sister and parents – and returns with him to Iran to visit the home he grew up in. The gifted student joined the ALP at just 16, wheeling and dealing his way through the Party and enjoying a meteoric rise to the Shadow Ministry. -

Australia's Silence on Tibet

AUSTRALIA’S SILENCE ON TIBET Australia Tibet Council 2017 How China is shaping our agenda AUSTRALIA’S SILENCE ON TIBET: How China is shaping our agenda Author: Kyinzom Dhongdue Editors: Kerri-Anne Chinn, Paul Bourke Australia Tibet Council acknowledges the input from the International Campaign for Tibet for this report. For further information on the issues raised in this report please email [email protected] ©Australia Tibet Council, September 2017 www.atc.org.au CONTENTS Executive summary 3 Chapter 1 - China’s influence on ustralianA politics and Tibet Australia’s response to Tibet 6 Chinese influence on Australian politics 8 Two Australian politicians with connections to China 11 Recommendations 12 Chapter 2 - China’s influence on Australian universities and Tibet A billion-dollar industry 13 Confucius Institutes 15 Case studies of two academics 18 Recommendations 19 Chapter 3 - Australia’s Tibetan community 20 Conclusion 22 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Under the leadership of the Dalai Lama, the Tibetans have earned widespread public support, with the Tibet cause continuing to test the conscience of world leaders. While China is far from winning over the international community on its policies in Tibet, in recent years it has been making rapid progress in numerous areas. Through a proactive foreign policy, utilising both economic leverage and soft power diplomacy, the Chinese government is making determined efforts to erode the support the Tibet movement has built up over many years. In Australia, China’s influence has infiltrated political and educational institutions, perhaps more than in any country in the western world. In fact, extensive reports in the Australian media over the past year have revealed an alarming level of Chinese influence in Australia.