Exploring the Implications of Using Grade Point Averages for Student Participation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Politics in Victoria: the Impact of Legislative Design, Policy

Water Politics in Victoria The impact of legislative design, policy objectives and institutional constraints on rural water supply governance Benjamin David Rankin Thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Swinburne Institute for Social Research Faculty of Health, Arts and Design Swinburne University of Technology 2017 i Abstract This thesis explores rural water supply governance in Victoria from its beginnings in the efforts of legislators during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to shape social and economic outcomes by legislative design and maximise developmental objectives in accordance with social liberal perspectives on national development. The thesis is focused on examining the development of Victorian water governance through an institutional lens with an intention to explain how the origins of complex legislative and administrative structures later come to constrain the governance of a policy domain (water supply). Centrally, the argument is concentrated on how the institutional structure comprising rural water supply governance encouraged future water supply endeavours that reinforced the primary objective of irrigated development at the expense of alternate policy trajectories. The foundations of Victoria’s water legislation were initially formulated during the mid-1880s and into the 1890s under the leadership of Alfred Deakin, and again through the efforts of George Swinburne in the decade following federation. Both regarded the introduction of water resources legislation as fundamentally important to ongoing national development, reflecting late nineteenth century colonial perspectives of state initiated assistance to produce social and economic outcomes. The objectives incorporated primarily within the Irrigation Act (1886) and later Water Acts later become integral features of water governance in Victoria, exerting considerable influence over water supply decision making. -

75 Years of Distinction

Swinburne: 75 Years of Distinction 1908 1983 f 11' . 44': 1 'LAM • Swinburne campus First students 1913 $ \ \ JNr.c 'RN£ IN;:snrr 'TE • .,.. T t:, 'E-f,v, 'L, 'd\. /l,,.._,. f,, •'.•✓ r,/j/ ( df I ..._ 7.,,,,,:-. I 11 ~.,,, · l.r,,,.,._, I II I I \ THIS BUJLDING WAS ERECTED IN THE YEAR 1917 :i~RI3~~G~N.SBY HADDON · ·· XRcmrEc The first seal Plaque, Art building Official badge An early crest Variation early crest A Swinburne family crest Coat of arms Book plate Seal. College ofT echnology Swinburne: 75 Years of Distinction Written by Bernard Hames Published by Swinburne College Press Contents Foreword 17 Establishment 19 • Diversification 26 The Depression 33 Post-war Innovation 35 The Swinburne Vision 46 Published by Swinburne College Press Text Copyright © Bernard Hames 1982 Illustration of Swinburne campus Copyright © Peter Schofield 1982 Typeset by Swinburne Graphic Design Centre in Italia Designed by David Whitbread, Swinburne Graphic Design Centre Printed by Gardner Printing Co. (Vic.) Pty Ltd 36 Thornton Crescent, Mitcham, Victoria 3132 All rights reserved ISBN O 85590 550 6 Foreword George Swinburne took him to vmious construction sites in England and Austria. and within three years he became a partner in the firm. while his uncle sailed for Australia to seek business opportunities Within the year George Swinburne followed his uncle to Melbourne and became immediately engrossed in setting up gas plants and bringing gas light to the cities and towns. Though most installations were in Victoria. they ranged from Albany to The Swinburnes lived for many generations in Cairns. In 1924, he was appointed Chairman of the Northumberland. -

Annual Report Annual 2010

Swinburne University of Technology ANNUAL REPORT 2010 Contents Annual Report (AR) Transmission letter AR : 1 Message from the Chancellor AR : 2 Message from the Vice-Chancellor AR : 4 Organisational profile AR : 8 The Coat of Arms AR : 8 Objectives AR : 9 Relevant Minister AR : 9 Nature and range of services AR : 9 Teaching divisions AR : 10 Governance AR : 11 Council AR : 11 Members of Swinburne Council AR : 12 Risk management AR : 16 Profiles of senior executives AR : 20 Swinburne at a glance AR : 21 Mission and Vision AR : 24 2010 Organisational performance AR : 26 Strategic goal 1 – Growth AR : 26 Strategic goal 2 – Transformational learning and teaching AR : 28 Strategic goal 3 – Transformational research AR : 32 Strategic goal 4 – Transformational culture AR : 36 Strategic goal 5 – Quality infrastructure AR : 40 Strategic goal 6 – Social inclusion, diversity and sustainability AR : 44 Strategic goal 7 – Internationalisation AR : 48 Statutory and Financial Report (SFR) Statutory reporting, compliance and disclosure statements SFR : 2 Building Act SFR : 2 Building works SFR : 2 Maintenance SFR : 2 Compliance SFR : 2 Environment SFR : 2 Consultancies SFR : 3 Education Services for Overseas Students (ESOS) SFR : 3 Freedom of Information (FOI) SFR : 4 Grievance and complaint handling procedures SFR : 5 Industrial relations SFR : 5 Merit and equity SFR : 5 National competition policy SFR : 6 Occupational Health and Safety SFR : 6 Notifiable incidents SFR : 6 Whistleblowers Protection Act SFR : 7 Information about the University SFR : -

Algernon Charles Swinburne: the Causes and Effects of His Sapphic

ALGERNON CHARLES SWINBURNE: THE CAUSES AND EFFECTS OF HIS SAPPHIC POSSESSION By ANTHEA MARGARET INGHAM A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of English College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham October 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The thesis regards the extraordinary power of Sappho in the 1860s as resulting in a form of “Sapphic Possession” which laid hold on Swinburne, shaped his verse, produced a provocative new poetics, and which accounted for a critical reception of his work that was both hostile and enthralled. Using biographical material and Freudian psychology, I show how Swinburne became attracted to Sappho and came to rely on her as a substitute mistress and particular kind of muse, and I demonstrate the pre-eminence of the Sapphic presence in Poems and Ballads: 1, as a dominant female muse who exacts peculiar sacrifices from the poet of subjection, necrophilia, and even a form of “death” in the loss of his own personality; as a result, he is finally reduced to acting as the muse’s mouthpiece, a state akin to that of Pythia or Sibyl. -

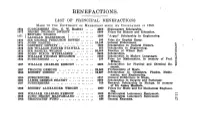

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE to the UNIVERSITY Oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION in 1853

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE TO THE UNIVERSITY oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION IN 1853. 1864 SUBSCRIBERS (Sec, G. W. Rusden) .. .. £866 Shakespeare Scholarship. 1871 HENRY TOLMAN DWIGHT 6000 Prizes for History and Education. 1871 j LA^HL^MACKmNON I 100° "ArSUS" S«h°lar8hiP ln Engineering. 1873 SIR GEORGE FERGUSON BOWEN 100 Prize for English Essay. 1873 JOHN HASTIE 19,140 General Endowment. 1873 GODFREY HOWITT 1000 Scholarships in Natural History. 1873 SIR WILLIAM FOSTER STAWELL 666 Scholarship in Engineering. 1876 SIR SAMUEL WILSON 30,000 Erection of Wilson Hall. 1883 JOHN DIXON WYSELASKIE 8400 Scholarships. 1884 WILLIAM THOMAS MOLLISON 6000 Scholarships in Modern Languages. 1884 SUBSCRIBERS 160 Prize for Mathematics, in memory of Prof. Wilson. 1887 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 2000 Scholarships for Physical and Chemical Re search. 1887 FRANCIS ORMOND 20,000 Professorship of Music. 1890 ROBERT DIXSON 10,887 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathe matics, and Engineering. 1890 SUBSCRIBERS 6217 Ormond Exhibitions in Music. 1891 JAMES GEORGE BEANEY 8900 Scholarships in Surgery and Pathology. 1897 SUBSCRIBERS 760 Research Scholarship In Biology, in memory of Sir James MacBain. 1902 ROBERT ALEXANDER WRIGHT 1000 Prizes for Music and for Mechanical Engineer ing. 1902 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 1000 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 JOHN HENRY MACFARLAND 100 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 GRADUATES' FUND 466 General Expenses. BENEFACTIONS (Continued). 1908 TEACHING STAFF £1160 General Expenses. oo including Professor Sponcer £2riS Professor Gregory 100 Professor Masson 100 1908 SUBSCRIBERS 106 Prize in memory of Alexander Sutherland. 1908 GEORGE McARTHUR Library of 2600 Books. 1004 DAVID KAY 6764 Caroline Kay Scholarship!!. 1904-6 SUBSCRIBERS TO UNIVERSITY FUND . -

ASSESSMENT of the BURWOOD ROAD HERITAGE PRECINCT, HAWTHORN with Assessment of the FORMER ADMINISTRATION BUILDING of SWINBURNE TECHNICAL COLLEGE

ASSESSMENT OF THE BURWOOD ROAD HERITAGE PRECINCT, HAWTHORN with assessment of the FORMER ADMINISTRATION BUILDING OF SWINBURNE TECHNICAL COLLEGE Prepared for the CITY OF BOROONDARA August 2008 JBA John Briggs Architect Conservation Consultant 331 A Bay Street Port Melbourne 3207 Mobile 0411 228 515 Phone 9681 9924 Fax 9681 9923 Schedule of Changes Issued Assessment of the Burwood Road Heritage Precinct adopted by 21 September 2009 Council Updated in accordance with Council resolution following Panel 5 March 2012 hearing in December 2011 to: Update citations Remove the properties at 453-477 (inclusive) Burwood Road from the study following their demolition Assessment of Burwood Road Heritage Precinct, Hawthorn JBA John Briggs Architects and Heritage Consultant Table of Contents Project Overview Introduction Methodology Recommendation Section 1 – Burwood Road Heritage Precinct Precinct citation Information sheets for buildings within the Precinct Section 2 – Individual Heritage Place Citation for: y Swinburne Technical College, former Administration Building Assessment of Burwood Road Heritage Precinct, Hawthorn JBA John Briggs Architects and Heritage Consultant Assessment of Burwood Road Heritage Precinct, Hawthorn Introduction The Assessment of the Burwood Road Heritage Precinct (‘the Precinct’) in Hawthorn was commissioned by the Ci ty of Boroondara and i ts outcomes are the ci tations for the Prec inct and for each of the buildings within the Precinct, as well as a citation for the former Administration Building of Swinburne Technical College in John Street. The Burwood Road Heritage Precinct comprises some 40 buildings currently in 29 titles fronting Burwood Road in the vicinity of the Swinburne University Campus and includes 4 buildings that make no contri bution to the heri tage significance of the Precinct. -

The Inaugural George Swinburne Memorial Lecture

Advanced Education: Still Advancing? The Inaugural George Swinburne Memorial Lecture Delivered on 30 October 1984 By Leslie Kilmartin, M.A., Ph.D, M.A.Ps.S. Dean Faculty of Arts Swinburne Institute of Technology GEORGE SWINBURNE MEMORIAL LECTURE This is the first of an annual lecture series instituted in honour of Swinburne's founder, the Hon. George Swinburne (1861-1928.) Mr Swinburne was a prominent Australian citizen who made major and diverse contributions to public life in the first quarter of this century. In the view of his biographer, however, the establishment of the college which now bears his name is "perhaps the most clean cut illustration of his genius". It is intended that this lecture series should pay tribute to George Swinburne's vision, by offering a public forum in which Swinburne teaching staff can display and discuss their contributions to advanced education, both to the Swinburne community and to the community at large. As an educational institution, Swinburne stands as testimony to the educational and social philosophy of its founder, the Hon. George Swinburne. Though markedly different from and advanced on his original concept, the present institution preserves the germ of his vision. In this lecture, I want to address the topic of the future of advanced education, a concept of which he could never have heard, but a development I am confident he would have applauded. Before tackling that tough question, however, I would like to tell you something about our founder, gleaned from my reading of several contemporary and recent sources. 1 Make no mistake: George Swinburne left his mark on the life of this State and even the nation. -

The Open Door, 1958

PUB: 8 Item 3(28)1 OPEN DOOR 1958 ZINE OF THE SWINBURNE TECHNICAL COLLEGE This year's cover is the work of third-year art student, Barbara Patterson, it symbolises the Jubilee Year and the varied activities associated with the College. THE OPEN DOOR JUBILEE EDITION Entrance to Swinburne Technical College. At this site on 19th September, 1908, the foundation stone was laid by Sir Thomas Bent, Premier of Victoria. The stone, darker in colour, is the seventh down from the sign OFFICE. George Swinburne, founder of Swinburne Technical College. THE OPEN DOOR 1958 The Magazine of the Swinburne Technical College THE OPEN DOOR | CONTENTS Foreword 5 Editorial 6 Introduction 7 Literary Section 8 Humour From The Past 83 General News 89 Personal Items 102 Clubs And Activities 112 Sport Record 123 Scholarship And Skill 131 For typing of the manuscript of this magazine thanks are extended to Barbara McKenzie, Lurline Archer, Valda Eliott, Marjorie Herbert, Pat Brown, Betty Solomon, Joan Brock, Estelle Hannah, Judith Winbanks and Margaret Reed. Miss Small, teacher-in-charge, is also thanked for her co-operation. FOREWORD I respond very gladly to your invitation to contribute a short foreword to the Jubilee Magazine. Last year we had to choose a name for a new University in Victoria, and we chose the name Monash, which has been accepted as symbolising for a University, which will have the pro motion of the practical sciences as a main object, the qualities we wish to emerge from that University. John Monash was an illus trious example of a man who gave the community, to an unexcelled degree, the benefits of his intense application to scientific training and wide culture. -

2020 Postgraduate Degrees and Pathways

2020 POSTGRADUATE DEGREES AND PATHWAYS INTERNATIONAL COURSE GUIDE Where you end up might not be where you started. But we’re here to go on that journey with you. Try new things, find friends from all over the world, and learn from experts in their field. Don’t just do what others tell you to do. Explore the unknown and grow comfortable with it. Wherever it takes you, we’ll make sure you’re ready for it. Swinburne is where your adventure begins. 2 2020 POSTGRADUATE GUIDE SWINBURNE CONTENTS ABOUT SWINBURNE Making our mark everywhere we go 4 From BHP to Swinburne 6 Australia’s first Nobel Peace Prize 7 Working on Sagrada Familia since 2000 8 Founder of Wonderla 9 Recognised and awarded 10 Everything your CV wants 11 Outstanding world-changing research 12 Our campuses 14 In the heart of Melbourne 16 Swinburne life is what you make it 18 The top 10 benefits of 20 being a Swinburne student Living in Melbourne 22 Scholarships 23 OUR COURSES Arts and Humanities 24 Aviation 26 Built Environment and Architecture 28 Business 31 Design 39 Education 41 Engineering 43 Health 47 Information Technology 50 Media and Communication 54 Psychology 56 Science 59 English language courses 61 FURTHER INFORMATION How to apply 62 Other information 63 3 MAKING OUR MARK EVERYWHERE WE GO With a qualification from Swinburne, you can go anywhere in the world. Melbourne. Milan. Malaysia. Our graduates are spread around the globe and work for some of the most dynamic organisations, from start-ups to not-for-profits to multinationals. -

Catalogue of Books in Robert Menzies Library.Pdf

CATALOGUE OF BOOKS CONTAINED IN SIR ROBERT MENZIES' LIB~~Y AT HIS HO~~ AT 2 HAVERBRACK AVENUE, Malvern (Nos. 1 to 26) AT HIS OFFICE, 95 Collins Street, Melbourne (A, B, c, D) I N D E X Australian miscellanea Misce llanea Dictionaries, etc. Australian Literature Literature Drama n Poetry Australian Biography "Literary" Biography Art Australian history - early History and Historical Biography History - 20th century Recent Biography Sir Winston Churchill American history ) Law Religion Description and Travel - Australian " • " - other Scotland Cricket Other Sports Food and Wine, etc. Political War - History War - Miscellanea Architecttrre and Planning International Affairs Reports Mystery A signed by the Author P Presented by publisher, organization, as a prize 2. Fire 26 uEE'er shelf 11 12 18 25 Door 19 6 French Window 5 24 1 Windmv B indicates the books in Sir Robert's bedroom \ .J ) AUSTRALIAN MISCELLANEA 1. * P - Presented A - Autographed * AUTHOR TITLE DATE P.orA. LOCATION ABBOTT, C. AUSTFALIA'S FRONTIER PROVINCE 1950 22c ) ADELAIDE ST. MARK'S COLLEGE - A HISTORY 1966 A 22b UNIVERSITY (A. Grenfell Price) ALEXANDER, Fred FROM CURTIN TO lYlENZIES AND AFTER 1973 A 15a ALPERS, O.T.J. CHEERFUL YESTERDAYS 1928 A 16b lIJ!JlERY , Leo S. THE AWAKENING: OUR PRESENT CRIS IS 1948 A 17b AND THE WAY OUT ANGELL, Norman THIS HAVE l\~D HAVE-NOT BUSINESS: 1936 23a POLITICAL FANTASY AND ECONOMIC FACT ARNDT, H. THE AUSTRALIAN ECONOMY: A VOLUME 1963 23a OF READINGS AUSTRALIA COMMITTEE OF ECONOMIC ENQUIRY 1965 23b Report v.I. AUSTRALIA EXTE~TAL AFFAIRS, DEPT. OF 1958 17d Consular representatives and trade coro~issioners in Australia AUSTRALIA PARLIAlY!ENT - HANDBOOK 1945-53 16b 1957-59 ) AUSTRALIA ROYAL COIYl!IIISSION ON THE 1929 13c CONSTITUTION - REPORT AUSTRALIA ROYAL VISIT, 1954 22c (Notes for planning the visit of H.M. -

Acknowledgement of Country I Would Like to Respectfully Acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the Land on Which We Gather, and P

p. 1 of 8 SPEECH PROFESSOR LINDA KRISTJANSON AO, VICE-CHANCELLOR Event: Installation Ceremony for Professor John Pollaers Date: Thursday, 23 May 2019 Location: Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre Acknowledgement of country I would like to respectfully acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which we gather, and pay respects to all Aboriginal Community Elders, past and present, who have resided in the area and have been an integral part of the history of this region. Welcome Thank you for joining us to warmly welcome Professor John Pollaers to Swinburne as our fifth Chancellor. I’m delighted to support John as he formally steps into his role. I am pleased to be working with him, guiding Swinburne through these exciting times, making the most of the opportunities before us. Swinburne is proud of its international standing Swinburne’s story goes all the way back to 1908, when it was founded by the engineer, businessman, philanthropist and politician, George Swinburne and his wife Ethel, as the Eastern Suburbs Technical College in Hawthorn. p. 2 of 8 As a university, we are young – only 27 years old. And in that short time we have become a world-class leader in education, research, innovation and entrepreneurship. The Times Higher Education University World Rankings place Swinburne in the top three per cent of universities worldwide. The QS World University Rankings also counts Swinburne among the top 400 universities worldwide, and in the ‘Top 50 Under 50’ years of age. Recently, we celebrated an exceptional outcome in the Excellence in Research for Australia (ERA) assessment. -

Benefactions

BENEFACTIONS LIST OF PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE TO THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION IN 1853 1S64 SUBSCRIBERS (Sec, G. W. Rusden) .. £856 Shakespeare Scholarship. 1871 HENRY TOLMAN DWIGHT 5,000 Prizes for History and Education. EDWARD WILSON | LACHLAN MACKINNON f 1,000 Argus Scholarship in Engineering. 1873 SIR GEORGE FERGUSON BOWEN .. 100 Prize for English Essay. JOHN HASTIE 19,140 General Endowment. GODFREY HOWITT 1,000 Scholarships in Natural History, SIR WILLIAM FOSTER STAWELL .. 655 Scholarship in Engineering. 1875 SIR SAMUEL WILSON 30.000 Erection of Wilson Hall. 1883 JOHN DIXON WYSELASKIE 8,400 Scholarships. 1884 WILLIAM THOMAS MOLLISON ., .. 6,000 Scholarships in Modern Languages. SUBSCRIBERS 150 Prize for Mathematics, in memory of Prof. Wilson. 1887 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT . .. 2,000 Scholarships for Physical and Chemical Research. FRANCIS ORMOND 20,000 Professorship of Music. 1890 ROBERT DIXSON 10,837 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathematics and Engineering. SUBSCRIBERS 5,217 Ormond Exhibitions in Music. 1891 JAMES GEORGE BEANEY 3,900 Scholarships in Surgery and Pathology, 1897 SUBSCRIBERS 760 Research Scholarship in Biology, in memory of Sir James MacBain. 1902 ROBERT ALEXANDER WRIGHT .... 1,000 Prizes for Musiic and for Mechanical Engineering. WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT .. .. 1,000 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 JOHN HENRY MACFARLAND .... 100 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment, GRADUATES' FUND 466 General Expenses. 1903 TEACHING STAFF 1,150 General Expenses. Including—• Professor Spencer .. .. £258 Professor Gregory . .. 100 Professor Masson ., . 100 SUBSCRIBERS 105 Prize in memory of Alexander Suther land. GEORGE McARTHUR Library of 2,500 Books. 1904 DAVID KAY 5,764 Caroline Kay Scholarships. 1904-6 SUBSCRIBERS TO UNIVERSITY FUND: President—Janet Lady Clarke Treasurer—Henry Butler Secretary—Charles Bage SPECIAL FOUNDATIONS- MRS.