The Permissive Politicians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herbert Vere Evatt, the United Nations and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights After 60 Years

238 (2009) 34 UWA LAW REVIEW Herbert Vere Evatt, the United Nations and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights After 60 Years MICHAEL KIRBY AC CMG* ERBERT VERE EVATT was a product of public schools. He attended Fort HStreet Boys’ High School in Sydney, the oldest public school in Australia, as I later did. That school has refl ected the ethos of public education in Australia: free, compulsory and secular. These values infl uenced Evatt’s values as they did my own.1 As an Australian lawyer, Evatt stood out. He was a Justice of the High Court of Australia for 10 years in the 1930s. However, his greatest fame was won by his leadership role in the formation of the United Nations and in the adoption of its Charter in 1945. He was elected the third President of the General Assembly. He was in the chair of the Assembly, on 10 December 1948, when it voted to accept the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).2 It is 60 years since that resolution of 1948. In the imagination of immature schoolchildren, like me, in the 1940s and 1950s, the Hiroshima cloud was imprinted on our consciousness. We knew (perhaps more than Australians do today) how important it was for the survival of the human species that the United Nations should be effective, including in the attainment of the values expressed in its new UDHR. When I arrived at high school in 1951, Evatt was honoured as a famous alumnus. By then, he was no longer a judge or Federal minister. -

Water Politics in Victoria: the Impact of Legislative Design, Policy

Water Politics in Victoria The impact of legislative design, policy objectives and institutional constraints on rural water supply governance Benjamin David Rankin Thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Swinburne Institute for Social Research Faculty of Health, Arts and Design Swinburne University of Technology 2017 i Abstract This thesis explores rural water supply governance in Victoria from its beginnings in the efforts of legislators during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to shape social and economic outcomes by legislative design and maximise developmental objectives in accordance with social liberal perspectives on national development. The thesis is focused on examining the development of Victorian water governance through an institutional lens with an intention to explain how the origins of complex legislative and administrative structures later come to constrain the governance of a policy domain (water supply). Centrally, the argument is concentrated on how the institutional structure comprising rural water supply governance encouraged future water supply endeavours that reinforced the primary objective of irrigated development at the expense of alternate policy trajectories. The foundations of Victoria’s water legislation were initially formulated during the mid-1880s and into the 1890s under the leadership of Alfred Deakin, and again through the efforts of George Swinburne in the decade following federation. Both regarded the introduction of water resources legislation as fundamentally important to ongoing national development, reflecting late nineteenth century colonial perspectives of state initiated assistance to produce social and economic outcomes. The objectives incorporated primarily within the Irrigation Act (1886) and later Water Acts later become integral features of water governance in Victoria, exerting considerable influence over water supply decision making. -

75 Years of Distinction

Swinburne: 75 Years of Distinction 1908 1983 f 11' . 44': 1 'LAM • Swinburne campus First students 1913 $ \ \ JNr.c 'RN£ IN;:snrr 'TE • .,.. T t:, 'E-f,v, 'L, 'd\. /l,,.._,. f,, •'.•✓ r,/j/ ( df I ..._ 7.,,,,,:-. I 11 ~.,,, · l.r,,,.,._, I II I I \ THIS BUJLDING WAS ERECTED IN THE YEAR 1917 :i~RI3~~G~N.SBY HADDON · ·· XRcmrEc The first seal Plaque, Art building Official badge An early crest Variation early crest A Swinburne family crest Coat of arms Book plate Seal. College ofT echnology Swinburne: 75 Years of Distinction Written by Bernard Hames Published by Swinburne College Press Contents Foreword 17 Establishment 19 • Diversification 26 The Depression 33 Post-war Innovation 35 The Swinburne Vision 46 Published by Swinburne College Press Text Copyright © Bernard Hames 1982 Illustration of Swinburne campus Copyright © Peter Schofield 1982 Typeset by Swinburne Graphic Design Centre in Italia Designed by David Whitbread, Swinburne Graphic Design Centre Printed by Gardner Printing Co. (Vic.) Pty Ltd 36 Thornton Crescent, Mitcham, Victoria 3132 All rights reserved ISBN O 85590 550 6 Foreword George Swinburne took him to vmious construction sites in England and Austria. and within three years he became a partner in the firm. while his uncle sailed for Australia to seek business opportunities Within the year George Swinburne followed his uncle to Melbourne and became immediately engrossed in setting up gas plants and bringing gas light to the cities and towns. Though most installations were in Victoria. they ranged from Albany to The Swinburnes lived for many generations in Cairns. In 1924, he was appointed Chairman of the Northumberland. -

Myth and Misrepresentation in Australian Foreign Policy Menzies and Engagement with Asia

BenvenutiMyth and Misrepresentation and Jones in Australian Foreign Policy Myth and Misrepresentation in Australian Foreign Policy Menzies and Engagement with Asia ✣ Andrea Benvenuti and David Martin Jones In 1960 the deputy leader of the Australian Labor Party, Gough Whitlam, declared that Australia “has for ten years missed the opportunity to interpret the new nations to the old world and the old world to the new na- tions.”1 Throughout the 1960s, Labor spokesmen attacked the foreign policy of Sir Robert Menzies’s Liberal–Country Party coalition government (1949– 1966) for both its dependence on powerful friends and its alleged insensitivity to Asian countries.2 This criticism of Liberal foreign policy not only persisted in later decades but also became the prevailing academic and media ortho- doxy.3 As we show here, Labor’s criticism constitutes the basis of a tenacious political myth that demands critical reevaluation. Menzies’s political opponents and, subsequently, his academic critics have claimed that his attitude toward Asia was permeated by suspicion and conde- scension. From the 1970s, an inchoate Labor left and academic understand- ing contended that conservative Anglo-centrism “had placed Australia on the losing side of almost every external engagement from the Suez Crisis to Viet- nam.”4 A decade later, analysts writing in the context of the Labor-driven doc- trine of “enmeshment” with Asia reinforced this emerging foreign policy or- 1. Gordon Greenwood and Norman Harper, eds., Australia in World Affairs 1956–1960 (Melbourne: Cheshire, 1963), p. 96. 2. See, for instance, Mads Clausen, “‘Falsiªed by History’: Menzies, Asia and Post-Imperial Australia,” History Compass, Vol. -

Annual Report Annual 2010

Swinburne University of Technology ANNUAL REPORT 2010 Contents Annual Report (AR) Transmission letter AR : 1 Message from the Chancellor AR : 2 Message from the Vice-Chancellor AR : 4 Organisational profile AR : 8 The Coat of Arms AR : 8 Objectives AR : 9 Relevant Minister AR : 9 Nature and range of services AR : 9 Teaching divisions AR : 10 Governance AR : 11 Council AR : 11 Members of Swinburne Council AR : 12 Risk management AR : 16 Profiles of senior executives AR : 20 Swinburne at a glance AR : 21 Mission and Vision AR : 24 2010 Organisational performance AR : 26 Strategic goal 1 – Growth AR : 26 Strategic goal 2 – Transformational learning and teaching AR : 28 Strategic goal 3 – Transformational research AR : 32 Strategic goal 4 – Transformational culture AR : 36 Strategic goal 5 – Quality infrastructure AR : 40 Strategic goal 6 – Social inclusion, diversity and sustainability AR : 44 Strategic goal 7 – Internationalisation AR : 48 Statutory and Financial Report (SFR) Statutory reporting, compliance and disclosure statements SFR : 2 Building Act SFR : 2 Building works SFR : 2 Maintenance SFR : 2 Compliance SFR : 2 Environment SFR : 2 Consultancies SFR : 3 Education Services for Overseas Students (ESOS) SFR : 3 Freedom of Information (FOI) SFR : 4 Grievance and complaint handling procedures SFR : 5 Industrial relations SFR : 5 Merit and equity SFR : 5 National competition policy SFR : 6 Occupational Health and Safety SFR : 6 Notifiable incidents SFR : 6 Whistleblowers Protection Act SFR : 7 Information about the University SFR : -

Algernon Charles Swinburne: the Causes and Effects of His Sapphic

ALGERNON CHARLES SWINBURNE: THE CAUSES AND EFFECTS OF HIS SAPPHIC POSSESSION By ANTHEA MARGARET INGHAM A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of English College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham October 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The thesis regards the extraordinary power of Sappho in the 1860s as resulting in a form of “Sapphic Possession” which laid hold on Swinburne, shaped his verse, produced a provocative new poetics, and which accounted for a critical reception of his work that was both hostile and enthralled. Using biographical material and Freudian psychology, I show how Swinburne became attracted to Sappho and came to rely on her as a substitute mistress and particular kind of muse, and I demonstrate the pre-eminence of the Sapphic presence in Poems and Ballads: 1, as a dominant female muse who exacts peculiar sacrifices from the poet of subjection, necrophilia, and even a form of “death” in the loss of his own personality; as a result, he is finally reduced to acting as the muse’s mouthpiece, a state akin to that of Pythia or Sibyl. -

Earle Page and the Imagining of Australia

‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA ‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA STEPHEN WILKS Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, Or what’s a heaven for? Robert Browning, ‘Andrea del Sarto’ The man who makes no mistakes does not usually make anything. Edward John Phelps Earle Page as seen by L.F. Reynolds in Table Talk, 21 October 1926. Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463670 ISBN (online): 9781760463687 WorldCat (print): 1198529303 WorldCat (online): 1198529152 DOI: 10.22459/NPM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This publication was awarded a College of Arts and Social Sciences PhD Publication Prize in 2018. The prize contributes to the cost of professional copyediting. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: Earle Page strikes a pose in early Canberra. Mildenhall Collection, NAA, A3560, 6053, undated. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Illustrations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Abbreviations . xiii Prologue: ‘How Many Germans Did You Kill, Doc?’ . xv Introduction: ‘A Dreamer of Dreams’ . 1 1 . Family, Community and Methodism: The Forging of Page’s World View . .. 17 2 . ‘We Were Determined to Use Our Opportunities to the Full’: Page’s Rise to National Prominence . -

Earle Page: an Active Treasurer

Earle Page: an active treasurer John Hawkins1 Earle Christmas Grafton Page brought down six Budgets while serving as Bruce’s treasurer. He was fortunate in when he was treasurer, after the war and before the Depression, which allowed him to ease tax burdens. Bruce and Page established the Loan Council and the National Debt Sinking Fund and introduced ‘tied grants’ to the States. Page moved the Commonwealth Bank further towards being a central bank and gave it responsibility for the note issue. Source: National Library of Australia 1 The author was formerly in Domestic Economy Division, the Australian Treasury. This article has benefited from discussions with Selwyn Cornish and the assistance of the Reserve Bank archivists. The views in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Australian Treasury. 55 Earle Page: an active treasurer Introduction As well as being a long-serving treasurer, Sir Earle Page PC GCMG served as prime minister for 20 days and was often acting prime minister. Only Billy Hughes has served a longer term in the House of Representatives. But as well as possessing longevity, Page was also innovative. His private secretary recalls him as ‘a combination of dreaming idealist and intensely practical man of affairs’.2 Indeed, he was described as ‘energetic, almost incoherent as he poured out ideas faster than words would come in an orderly fashion’, peppered with his trademark ‘you see, you see’.3 He not only had a lot of energy for his ideas and his politics. Physically robust, Page played a daily hard game of tennis until he was over 80, and ‘he played it as he played the political game, with reckless energy, native cunning and a certain contempt for the orthodox rules of the game’.4 His energy was accompanied by an ability to get on well with most of his colleagues. -

Thesis-Putland-2013-14Bibliog.Pdf

BIBLIOGRAPHY – checking a Race PRIMARY SOURCES National Archives of Australia National Archives of Australia: Prime Minister's Department; A457 Correspondence files, multiple number series, first system, 1915 – 1923; 501/16, Medical. Tuberculosis, 1916-1922; Memorandum, J.H.L. Cumpston to Prime Minister Hughes, 2 April, 1917. Letter, Prime Minister to Premier of Victoria, 18 April, 1917. Letter, Premier of Victoria to Prime Minister, 17 May 1917. Letter, Prime Minister to Premier of Victoria, 23 July 1917. Letter, Premier of Victoria to Prime Minister, 10 December 1917. Letter, Prime Minister to Premier of Victoria, 8 March 1918. Letter, Premier of Victoria to Prime Minister, 1 May 1918. Letter, Prime Minister to Premier of Victoria, 5 September 1918. Letter, Premier of Victoria to Prime Minister, 19 February, 1920. Letter, Prime Minister to Premier of Victoria, 19 August, 1920. Letter, Premier of Victoria to Prime Minister, 11 November, 1920. Memorandum, J.H.L. Cumpston, Director of Quarantine to Deane, Secretary to Prime Minister, 7 February 1921. Letter, Prime Minister to Premier of Victoria, 8 April, 1921. Report, Prime Minister’s Office, 9 March, 1922. Letter, Premier of Western Australia to Prime Minister, 22 May 1922. National Archives of Australia: 20 October 1914 – 31 December 1920 CA 2001, Australian Imperial Force, Base Records Office, B2455, First Australian Imperial Force Personnel Dossiers, 1941-1920, 1 January 1914 -31 December 1920, Putland Samuel Joseph: Service Number – 1974: Place of Birth – Glen Burn SA: Place of Enlistment – Adelaide SA: Next of Kin – (Father) Putland Frederick, 1941 – 1920, Certificate of Medical Examination National Archives of Australia: Secretary to Cabinet/Cabinet Secretariat; A2717 Hughes Ministry - Folders of agenda and decisions, 1919-1922; VOLUME 1 FOLDER 3, [Hughes Ministry Cabinet Decisions] Jan to Oct. -

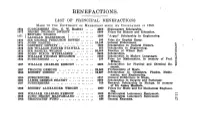

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE to the UNIVERSITY Oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION in 1853

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE TO THE UNIVERSITY oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION IN 1853. 1864 SUBSCRIBERS (Sec, G. W. Rusden) .. .. £866 Shakespeare Scholarship. 1871 HENRY TOLMAN DWIGHT 6000 Prizes for History and Education. 1871 j LA^HL^MACKmNON I 100° "ArSUS" S«h°lar8hiP ln Engineering. 1873 SIR GEORGE FERGUSON BOWEN 100 Prize for English Essay. 1873 JOHN HASTIE 19,140 General Endowment. 1873 GODFREY HOWITT 1000 Scholarships in Natural History. 1873 SIR WILLIAM FOSTER STAWELL 666 Scholarship in Engineering. 1876 SIR SAMUEL WILSON 30,000 Erection of Wilson Hall. 1883 JOHN DIXON WYSELASKIE 8400 Scholarships. 1884 WILLIAM THOMAS MOLLISON 6000 Scholarships in Modern Languages. 1884 SUBSCRIBERS 160 Prize for Mathematics, in memory of Prof. Wilson. 1887 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 2000 Scholarships for Physical and Chemical Re search. 1887 FRANCIS ORMOND 20,000 Professorship of Music. 1890 ROBERT DIXSON 10,887 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathe matics, and Engineering. 1890 SUBSCRIBERS 6217 Ormond Exhibitions in Music. 1891 JAMES GEORGE BEANEY 8900 Scholarships in Surgery and Pathology. 1897 SUBSCRIBERS 760 Research Scholarship In Biology, in memory of Sir James MacBain. 1902 ROBERT ALEXANDER WRIGHT 1000 Prizes for Music and for Mechanical Engineer ing. 1902 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 1000 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 JOHN HENRY MACFARLAND 100 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 GRADUATES' FUND 466 General Expenses. BENEFACTIONS (Continued). 1908 TEACHING STAFF £1160 General Expenses. oo including Professor Sponcer £2riS Professor Gregory 100 Professor Masson 100 1908 SUBSCRIBERS 106 Prize in memory of Alexander Sutherland. 1908 GEORGE McARTHUR Library of 2600 Books. 1004 DAVID KAY 6764 Caroline Kay Scholarship!!. 1904-6 SUBSCRIBERS TO UNIVERSITY FUND . -

The 46Th Parliament, Parliamentary Handbook of the Commonwealth Of

Index Index Note: Senators and Members listed in the index are restricted to those of the 46th Parliament. For a full alphabetical listing of Senators and Members of the Parliament since 1901 see pp. 468–563. A B Abbott Ministry 2013–15 585, 677–9 Balaclava 374 abbreviations viii–xv members 1901–84 319 honours, orders and decorations xiii–xiv Ballarat 374, 403 others xiv–xv members since 1901 319 political affiliations viii–ix origin of name 378 qualifications ix–xiii Bandt, AP, MP 17, 42, 263, 356, 499 Abetz, Senator the Hon. E 15, 30, 259, 276, 468, Banks 375, 391, 392 656, 659, 661, 662, 677, 678, 680, 683, 716–20 members since 1949 320 Aboriginals Referendum 1967 430 origin of name 378 Adelaide 374, 400 Barker 374, 399 members since 1903 318 members since 1903 320 origin of name 378 origin of name 378 Advance Australia Fair 447 Barrier 374 age of Senators and Members (current) 258 members 1901–22 320 Albanese, the Hon. AN, MP 14, 17, 24, 31, 262, 341, Barton 375, 392 497, 583, 663, 665–75, 705, 707–14, 722–6 members since 1922 320 Alexander, JG, MP 17, 32, 263, 322, 497 origin of name 378 Allen, Dr KJ, MP 17, 33–4, 265, 344, 497, 572 Barton Ministry 1901–03 584, 586 Aly, Dr A, MP 17, 35, 264, 276, 330, 497, 572 Bass 374, 401 Andrews, the Hon. KJ, MP 14, 17, 37, 262, 356, 498, members since 1903 321 657–63, 679–83, 687, 700, 702, 703, 717, 718 origin of name 378 Andrews, the Hon. -

ASSESSMENT of the BURWOOD ROAD HERITAGE PRECINCT, HAWTHORN with Assessment of the FORMER ADMINISTRATION BUILDING of SWINBURNE TECHNICAL COLLEGE

ASSESSMENT OF THE BURWOOD ROAD HERITAGE PRECINCT, HAWTHORN with assessment of the FORMER ADMINISTRATION BUILDING OF SWINBURNE TECHNICAL COLLEGE Prepared for the CITY OF BOROONDARA August 2008 JBA John Briggs Architect Conservation Consultant 331 A Bay Street Port Melbourne 3207 Mobile 0411 228 515 Phone 9681 9924 Fax 9681 9923 Schedule of Changes Issued Assessment of the Burwood Road Heritage Precinct adopted by 21 September 2009 Council Updated in accordance with Council resolution following Panel 5 March 2012 hearing in December 2011 to: Update citations Remove the properties at 453-477 (inclusive) Burwood Road from the study following their demolition Assessment of Burwood Road Heritage Precinct, Hawthorn JBA John Briggs Architects and Heritage Consultant Table of Contents Project Overview Introduction Methodology Recommendation Section 1 – Burwood Road Heritage Precinct Precinct citation Information sheets for buildings within the Precinct Section 2 – Individual Heritage Place Citation for: y Swinburne Technical College, former Administration Building Assessment of Burwood Road Heritage Precinct, Hawthorn JBA John Briggs Architects and Heritage Consultant Assessment of Burwood Road Heritage Precinct, Hawthorn Introduction The Assessment of the Burwood Road Heritage Precinct (‘the Precinct’) in Hawthorn was commissioned by the Ci ty of Boroondara and i ts outcomes are the ci tations for the Prec inct and for each of the buildings within the Precinct, as well as a citation for the former Administration Building of Swinburne Technical College in John Street. The Burwood Road Heritage Precinct comprises some 40 buildings currently in 29 titles fronting Burwood Road in the vicinity of the Swinburne University Campus and includes 4 buildings that make no contri bution to the heri tage significance of the Precinct.