Algernon Charles Swinburne: the Causes and Effects of His Sapphic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Politics in Victoria: the Impact of Legislative Design, Policy

Water Politics in Victoria The impact of legislative design, policy objectives and institutional constraints on rural water supply governance Benjamin David Rankin Thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Swinburne Institute for Social Research Faculty of Health, Arts and Design Swinburne University of Technology 2017 i Abstract This thesis explores rural water supply governance in Victoria from its beginnings in the efforts of legislators during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to shape social and economic outcomes by legislative design and maximise developmental objectives in accordance with social liberal perspectives on national development. The thesis is focused on examining the development of Victorian water governance through an institutional lens with an intention to explain how the origins of complex legislative and administrative structures later come to constrain the governance of a policy domain (water supply). Centrally, the argument is concentrated on how the institutional structure comprising rural water supply governance encouraged future water supply endeavours that reinforced the primary objective of irrigated development at the expense of alternate policy trajectories. The foundations of Victoria’s water legislation were initially formulated during the mid-1880s and into the 1890s under the leadership of Alfred Deakin, and again through the efforts of George Swinburne in the decade following federation. Both regarded the introduction of water resources legislation as fundamentally important to ongoing national development, reflecting late nineteenth century colonial perspectives of state initiated assistance to produce social and economic outcomes. The objectives incorporated primarily within the Irrigation Act (1886) and later Water Acts later become integral features of water governance in Victoria, exerting considerable influence over water supply decision making. -

75 Years of Distinction

Swinburne: 75 Years of Distinction 1908 1983 f 11' . 44': 1 'LAM • Swinburne campus First students 1913 $ \ \ JNr.c 'RN£ IN;:snrr 'TE • .,.. T t:, 'E-f,v, 'L, 'd\. /l,,.._,. f,, •'.•✓ r,/j/ ( df I ..._ 7.,,,,,:-. I 11 ~.,,, · l.r,,,.,._, I II I I \ THIS BUJLDING WAS ERECTED IN THE YEAR 1917 :i~RI3~~G~N.SBY HADDON · ·· XRcmrEc The first seal Plaque, Art building Official badge An early crest Variation early crest A Swinburne family crest Coat of arms Book plate Seal. College ofT echnology Swinburne: 75 Years of Distinction Written by Bernard Hames Published by Swinburne College Press Contents Foreword 17 Establishment 19 • Diversification 26 The Depression 33 Post-war Innovation 35 The Swinburne Vision 46 Published by Swinburne College Press Text Copyright © Bernard Hames 1982 Illustration of Swinburne campus Copyright © Peter Schofield 1982 Typeset by Swinburne Graphic Design Centre in Italia Designed by David Whitbread, Swinburne Graphic Design Centre Printed by Gardner Printing Co. (Vic.) Pty Ltd 36 Thornton Crescent, Mitcham, Victoria 3132 All rights reserved ISBN O 85590 550 6 Foreword George Swinburne took him to vmious construction sites in England and Austria. and within three years he became a partner in the firm. while his uncle sailed for Australia to seek business opportunities Within the year George Swinburne followed his uncle to Melbourne and became immediately engrossed in setting up gas plants and bringing gas light to the cities and towns. Though most installations were in Victoria. they ranged from Albany to The Swinburnes lived for many generations in Cairns. In 1924, he was appointed Chairman of the Northumberland. -

Poet's Corner in Westminster Abbey

Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey Alton Barbour Abstract: Beginning with a brief account of the history of Westminster Abbey and its physical structure, this paper concentrates on the British writers honored in the South Transept or Poet’s Corner section. It identifies those recognized who are no longer thought to be outstanding, those now understood to be outstanding who are not recognized, and provides an alphabetical listing of the honored members of dead poet’s society, Britain’s honored writers, along with the works for which they are best known. Key terms: Poet’s Corner, Westminster Abbey, South Transept. CHRISTIANITY RETURNS AND CHURCHES ARE BUILT A walk through Westminster Abbey is a walk through time and through English history from the time of the Norman conquest. Most of that journey is concerned with the crowned heads of England, but not all. One section of the Abbey has been dedicated to the major figures in British literature. This paper is concerned mainly with the major poets, novelists and dramatists of Britain, but that concentration still requires a little historical background. For over nine centuries, English monarchs have been both crowned and buried in Westminster Abbey. The Angles, Saxons and Jutes who conquered and occupied England in the mid 5th century were pagans. But, as the story goes, Pope Gregory saw two fair-haired boys in the Roman market who were being sold as slaves and asked who they were. He was told that they were Angles. He replied that they looked more like angels (angeli more than angli) and determined that these pagan people should be converted to Christianity. -

Annual Report Annual 2010

Swinburne University of Technology ANNUAL REPORT 2010 Contents Annual Report (AR) Transmission letter AR : 1 Message from the Chancellor AR : 2 Message from the Vice-Chancellor AR : 4 Organisational profile AR : 8 The Coat of Arms AR : 8 Objectives AR : 9 Relevant Minister AR : 9 Nature and range of services AR : 9 Teaching divisions AR : 10 Governance AR : 11 Council AR : 11 Members of Swinburne Council AR : 12 Risk management AR : 16 Profiles of senior executives AR : 20 Swinburne at a glance AR : 21 Mission and Vision AR : 24 2010 Organisational performance AR : 26 Strategic goal 1 – Growth AR : 26 Strategic goal 2 – Transformational learning and teaching AR : 28 Strategic goal 3 – Transformational research AR : 32 Strategic goal 4 – Transformational culture AR : 36 Strategic goal 5 – Quality infrastructure AR : 40 Strategic goal 6 – Social inclusion, diversity and sustainability AR : 44 Strategic goal 7 – Internationalisation AR : 48 Statutory and Financial Report (SFR) Statutory reporting, compliance and disclosure statements SFR : 2 Building Act SFR : 2 Building works SFR : 2 Maintenance SFR : 2 Compliance SFR : 2 Environment SFR : 2 Consultancies SFR : 3 Education Services for Overseas Students (ESOS) SFR : 3 Freedom of Information (FOI) SFR : 4 Grievance and complaint handling procedures SFR : 5 Industrial relations SFR : 5 Merit and equity SFR : 5 National competition policy SFR : 6 Occupational Health and Safety SFR : 6 Notifiable incidents SFR : 6 Whistleblowers Protection Act SFR : 7 Information about the University SFR : -

The Christmas Poems of Robert Herrick

Now, Now The Mirth Comes Now, Now The Mirth Comes Christmas Poetry by Robert Herrick Christs Birth. One Birth our Saviour had; the like none yet Was, or will be a second like to it. The Virgin Mary. To work a wonder, God would have her shown, At once, a Bud, and yet a Rose full-blowne. Compiled and Edited By Douglas D. Anderson 2007 Now, Now Comes The Mirth Christmas Poetry by Robert Herrick Douglas D. Anderson 2007 Cover Art: “The Boar's Head” Harper's Monthly Jan 1873 The text of this book was set in 12 point Palatino Linotype; Display used throughout is Arial. Printed and Published by Lulu, Inc. Morrisville, North Carolina 27560 Lulu ID 871847 http://www.lulu.com/content/ 871847 Douglas Anderson's Christmas Storefront http://stores.lulu.com/carols_book Christmas Poetry By Robert Herrick Contents Christmas Eve On Christmas Eve (“Come Bring The Noise”) On Christmas Eve (“Come, Guard This Night”) Christmas An Ode Of The Birth Of Our Saviour A Christmas Carol ("What sweeter music can we bring") Tell Us, Thou Cleere And Heavenly Tongue (Also known as The Star Song) The New Year A New Year's Gift Sent To Sir Simeon Steward The New-Year's Gift (“Let others look for pearl and gold”) The New-yeeres Gift, or Circumcisions Song, Sung to the King in the Presence at White-Hall. Another New-yeeres Gift, or Song for the Circumcision To His Saviour. The New Year's Gift Epiphany Twelfth Night, or King and Queen (“Now, Now, The Mirth Comes”) St. -

The Sacred and the Secular

Part 3 The Sacred and the Secular Allegory of Fleeting Time, c. 1634. Antonio Pereda. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria. “I write of groves, of twilights, and I sing L The court of Mab, and of the Fairy King. I write of hell; I sing (and ever shall) Of heaven, and hope to have it after all.” —Robert Herrick, “The Argument of His Book” 413 Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY 00413413 U2P3-845482.inddU2P3-845482.indd 413413 11/29/07/29/07 10:19:5210:19:52 AMAM BEFORE YOU READ from the King James AKG Images Version of the Bible he Bible is a collection of writings belong- ing to the sacred literature of Judaism and- TChristianity. Although most people think of the Bible as a single book, it is actually a collec- tion of books. In fact, the word Bible comes from the Greek words ta biblia, meaning “the little books.” The Hebrew Bible, also called the Tanakh, contains the sacred writings of the Jewish people and chronicles their history. The Christian Bible was originally written in Greek. It contains most of the same texts as the Hebrew Bible, as well as twenty-seven additional books called the New Testament. The many books of the Bible were written at different times and contain various types The Creation of Heaven and Earth (detail of writing—including history, law, stories, songs, from the Chaos), 1200. Mosaic. Monreale proverbs, sermons, prophecies, and letters. Cathedral, Sicily. Protestants living in Switzerland; and the Rheims- “I perceived how that it was impossible Douay Bible, translated by English Roman to establish the lay people in any truth Catholics living in France. -

FRANCIS TURNER PALGRAVE and the GOLDEN TREASURY By

FRANCIS TURNER PALGRAVE AND THE GOLDEN TREASURY By MEGAN JANE NELSON M. A., Flinders University of South Australia, 1978 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of English) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1985 (^Megan Jane Nelson, 1985 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. English Department of The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date 15 April 1985 )E-6 (3/81) ii ABSTRACT In spite of the enormous resurgence of critical interest in minor figures of the Victorian era over the last twenty years, almost no attention has been paid to Francis Turner Palgrave (1824-1897). In his own age, he was respected as a man of letters, educator, art critic, poet, friend of Alfred Tennyson, and editor of The Golden Treasury of the Best Songs and Lyrical Poems in the English Language, first published in 1861. This dissertation attempts to make good that neglect in two ways: firstly, through an analysis of his life and times, an assessment of his writings as an art and literary critic, an examination of his considerable corpus of original poetry, and the compilation of the first comprehensive bibliography of his own publications. -

Stuart Debauchery in Restoration Satire

Stuart Debauchery in Restoration Satire Neal Hackler A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the PhD degree in English Supervised by Dr. Nicholas von Maltzahn Department of English Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Neal Hackler, Ottawa, Canada, 2015. ii Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ iii Abstract .............................................................................................................................. iv List of Figures and Illustrations.............................................................................................v List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... vi Note on Poems on Affairs of State titles ............................................................................. vii Stuart Debauchery in Restoration Satire Introduction – Making a Merry Monarch...................................................................1 Chapter I – Abundance, Excess, and Eikon Basilike ..................................................8 Chapter II – Debauchery and English Constitutions ................................................. 66 Chapter III – Rochester, “Rochester,” and more Rochester .................................... 116 Chapter IV – Satirists and Secret Historians .......................................................... 185 Conclusion -

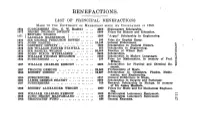

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE to the UNIVERSITY Oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION in 1853

BENEFACTIONS. LIST OP PRINCIPAL BENEFACTIONS MADE TO THE UNIVERSITY oi' MKLBOUKNE SINCE ITS FOUNDATION IN 1853. 1864 SUBSCRIBERS (Sec, G. W. Rusden) .. .. £866 Shakespeare Scholarship. 1871 HENRY TOLMAN DWIGHT 6000 Prizes for History and Education. 1871 j LA^HL^MACKmNON I 100° "ArSUS" S«h°lar8hiP ln Engineering. 1873 SIR GEORGE FERGUSON BOWEN 100 Prize for English Essay. 1873 JOHN HASTIE 19,140 General Endowment. 1873 GODFREY HOWITT 1000 Scholarships in Natural History. 1873 SIR WILLIAM FOSTER STAWELL 666 Scholarship in Engineering. 1876 SIR SAMUEL WILSON 30,000 Erection of Wilson Hall. 1883 JOHN DIXON WYSELASKIE 8400 Scholarships. 1884 WILLIAM THOMAS MOLLISON 6000 Scholarships in Modern Languages. 1884 SUBSCRIBERS 160 Prize for Mathematics, in memory of Prof. Wilson. 1887 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 2000 Scholarships for Physical and Chemical Re search. 1887 FRANCIS ORMOND 20,000 Professorship of Music. 1890 ROBERT DIXSON 10,887 Scholarships in Chemistry, Physics, Mathe matics, and Engineering. 1890 SUBSCRIBERS 6217 Ormond Exhibitions in Music. 1891 JAMES GEORGE BEANEY 8900 Scholarships in Surgery and Pathology. 1897 SUBSCRIBERS 760 Research Scholarship In Biology, in memory of Sir James MacBain. 1902 ROBERT ALEXANDER WRIGHT 1000 Prizes for Music and for Mechanical Engineer ing. 1902 WILLIAM CHARLES KERNOT 1000 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 JOHN HENRY MACFARLAND 100 Metallurgical Laboratory Equipment. 1903 GRADUATES' FUND 466 General Expenses. BENEFACTIONS (Continued). 1908 TEACHING STAFF £1160 General Expenses. oo including Professor Sponcer £2riS Professor Gregory 100 Professor Masson 100 1908 SUBSCRIBERS 106 Prize in memory of Alexander Sutherland. 1908 GEORGE McARTHUR Library of 2600 Books. 1004 DAVID KAY 6764 Caroline Kay Scholarship!!. 1904-6 SUBSCRIBERS TO UNIVERSITY FUND . -

The Lyrical Poems of Robert Herrick

The Lyrical Poems Of Robert Herrick Francis Turner Palgrave *The Project Gutenberg Etext of Lyrical Poems Of Robert Herrick* Arranged with introduction by Francis Turner Palgrave Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before posting these files!! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Do not remove this. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. A Selection From The Lyrical Poems Of Robert Herrick Arranged with introduction by Francis Turner Palgrave February, 1998 [Etext #1211] *The Project Gutenberg Etext of Lyrical Poems Of Robert Herrick* ******This file should be named 1rbnh10.txt or 1rbnh10.zip****** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, 1rbnh11.txt VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, 1rbnh10a.txt Project Gutenberg Etexts are usually created from multiple editions, all of which are in the Public Domain in the United States, unless a copyright notice is included. Therefore, we do NOT keep these books in compliance with any particular paper edition, usually otherwise. We are now trying to release all our books one month in advance of the official release dates, for time for better editing. Please note: neither this list nor its contents are final till midnight of the last day of the month of any such announcement. -

ASSESSMENT of the BURWOOD ROAD HERITAGE PRECINCT, HAWTHORN with Assessment of the FORMER ADMINISTRATION BUILDING of SWINBURNE TECHNICAL COLLEGE

ASSESSMENT OF THE BURWOOD ROAD HERITAGE PRECINCT, HAWTHORN with assessment of the FORMER ADMINISTRATION BUILDING OF SWINBURNE TECHNICAL COLLEGE Prepared for the CITY OF BOROONDARA August 2008 JBA John Briggs Architect Conservation Consultant 331 A Bay Street Port Melbourne 3207 Mobile 0411 228 515 Phone 9681 9924 Fax 9681 9923 Schedule of Changes Issued Assessment of the Burwood Road Heritage Precinct adopted by 21 September 2009 Council Updated in accordance with Council resolution following Panel 5 March 2012 hearing in December 2011 to: Update citations Remove the properties at 453-477 (inclusive) Burwood Road from the study following their demolition Assessment of Burwood Road Heritage Precinct, Hawthorn JBA John Briggs Architects and Heritage Consultant Table of Contents Project Overview Introduction Methodology Recommendation Section 1 – Burwood Road Heritage Precinct Precinct citation Information sheets for buildings within the Precinct Section 2 – Individual Heritage Place Citation for: y Swinburne Technical College, former Administration Building Assessment of Burwood Road Heritage Precinct, Hawthorn JBA John Briggs Architects and Heritage Consultant Assessment of Burwood Road Heritage Precinct, Hawthorn Introduction The Assessment of the Burwood Road Heritage Precinct (‘the Precinct’) in Hawthorn was commissioned by the Ci ty of Boroondara and i ts outcomes are the ci tations for the Prec inct and for each of the buildings within the Precinct, as well as a citation for the former Administration Building of Swinburne Technical College in John Street. The Burwood Road Heritage Precinct comprises some 40 buildings currently in 29 titles fronting Burwood Road in the vicinity of the Swinburne University Campus and includes 4 buildings that make no contri bution to the heri tage significance of the Precinct. -

The Critics: Poetry Is About Poetry 23 V

Love and its Critics From the Song of Songs to Shakespeare and Milton’s Eden MICHAEL BRYSON AND ARPI MOVSESIAN To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/611 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Love and its Critics From the Song of Songs to Shakespeare and Milton’s Eden Michael Bryson and Arpi Movsesian https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2017 Michael Bryson and Arpi Movsesian This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Michael Bryson and Arpi Movsesian, Love and its Critics: From the Song of Songs to Shakespeare and Milton’s Eden. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2017, https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0117 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/611#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.