The Recipe for Rebirth: Cacao As Fish in the Mythology and Symbolism of the Ancient Maya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Ceramic Musical Instruments from Coastal Oaxaca, Mexico Guy David Heppa, Sarah B

This article was downloaded by: [Arthur Joyce] On: 15 May 2014, At: 09:17 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK World Archaeology Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rwar20 Communing with nature, the ancestors and the neighbors: ancient ceramic musical instruments from coastal Oaxaca, Mexico Guy David Heppa, Sarah B. Barberb & Arthur A. Joycea a Department of Anthropology, University of Colorado b Department of Anthropology, University of Central Florida Published online: 13 May 2014. To cite this article: Guy David Hepp, Sarah B. Barber & Arthur A. Joyce (2014): Communing with nature, the ancestors and the neighbors: ancient ceramic musical instruments from coastal Oaxaca, Mexico, World Archaeology To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2014.909100 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Metaphors of Relative Elevation, Position and Ranking in Popol Vuh

METAPHORS OF RELATIVE ELEVATION, POSITION AND RANKING IN POPOL VUH Nathaniel TARN and Martin PRECHTEL Rutgers University This paper is an account of work very much in progress on the textual analysis of Popol V uh, and is one study among others (since this theme is attracting a number of students today) of inter-con nections and mutual illuminations between Popol Vuh and the con temporary ethnographic record in Highland Guatemala and Chiapas. For some considerable time now Popol Vuh has been considered as the major extant text of the Mesoamerican literary traditions, and as one of the most remarkable of all human creation stories, both for its beauty and for the complexity of its cosmological and mythical messages. While it may or may not have had a hieroglyphic original, the present alphabetic version of Po pol V uh wars written down some where between 1545 and 1558 by an anonymous member of the Cavek lineage of the Quiche Maya of Guatemala. This lineage had been a ruling house until it fell to the Spaniards in 1524. The manu script was copied by Francisco de Ximenez, a Spanish priest, some 150 years later. While there are references to Christianity in the text, these are few and it is generally regarded as one of the purest extant accounts of prehispanic Maya world-view. At the end of the hook, what we call mythical history shades into the historical history of the Quiche, so that the hook can serve as an illustration of the extent to which these two kinds of history are not held a,part by Maya generally. -

The Political, Ideological, and Economic Significance of Ancient Maya Iron-Ore Mirrors

SURFACES AND BEYOND: THE POLITICAL, IDEOLOGICAL, AND ECONOMIC SIGNIFICANCE OF ANCIENT MAYA IRON-ORE MIRRORS A Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Arts and Science TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada © Copyright by Marc Gordon Blainey Anthropology M.A. Program June 2007 ABSTRACT Surfaces and Beyond: The Political, Ideological, and Economic Significance of Ancient Maya Iron-ore Mirrors Marc Gordon Blainey This thesis examines archaeological evidence pertaining to composite lithic artifacts of the ancient Maya termed “mirrors.” These objects, typically consisting of flat, shiny iron-ore fragments fitted in a mosaic to a backing of stone, ceramic, or wood, are assessed concerning their political, ideological, and economic implications within ancient Maya society. The evidence, including detailed archaeological proveniences and instances of mirrors in iconography, epigraphy, and ethnohistory, is considered from the theoretical standpoints of cognitive archaeology, from the perspectives of shamanism, and a renewed conjunctive approach. Endeavouring to reveal the emic significance mirrors held for the ancient Maya who made and used them, the role of these mirrors is situated within the broader ideological framework of a reflective surface complex. Although prior interpretations are largely correct in designating mirrors as implements for “divinatory scrying,” it is concluded that the evidence allows for a much more refined elucidation than has heretofore been provided. Keywords: ancient Maya, mirrors, iron-ore, archaeology, shamanism, scrying, prestige goods ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my family, particularly my parents, John and Sue Blainey. -

The Toltec Invasion and Chichen Itza

Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include: Breaking the Maya Code Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs Angkor and the Khmer Civilization India: A Short History The Incas The Aztecs See our websites www.thamesandhudson.com www.thamesandhudsonusa.com 7 THE POSTCLASSIC By the close of the tenth century AD the destiny of the once proud and independent Maya had, at least in northern Yucatan, fallen into the hands of grim warriors from the highlands of central Mexico, where a new order of men had replaced the supposedly more intellectual rulers of Classic times. We know a good deal about the events that led to the conquest of Yucatan by these foreigners, and the subsequent replacement of their state by a resurgent but already decadent Maya culture, for we have entered into a kind of history, albeit far more shaky than that which was recorded on the monuments of the Classic Period. The traditional annals of the peoples of Yucatan, and also of the Guatemalan highlanders, transcribed into Spanish letters early in Colonial times, apparently reach back as far as the beginning of the Postclassic era and are very important sources. But such annals should be used with much caution, whether they come to us from Bishop Landa himself, from statements made by the native nobility, or from native lawsuits and land claims. These are often confused and often self-contradictory, not least because native lineages seem to have deliberately falsified their own histories for political reasons. Our richest (and most treacherous) sources are the K’atun Prophecies of Yucatan, contained in the “Books of Chilam Balam,” which derive their name from a Maya savant said to have predicted the arrival of the Spaniards from the east. -

Panthéon Maya

Liste des divinités et des démons de la mythologie des mayas. Les noms sont tirés du Popol Vuh des Mayas Quichés, des livres de Chilam Balam et de Diego de Landa ainsi que des divers codex. Divinité Dieu Déesse Démon Monstre Animal Humain AB KIN XOC Dieu de poésie. ACAN Dieu des boissons fermentées et de l'ivresse. ACANTUN Quatre démons associés à une couleur et à un point cardinal. Ils sont présents lors du nouvel an maya et lors des cérémonies de sculpture des statues. ACAT Dieu des tatouages. AH CHICUM EK Autre nom de Xamen Ek. AH CHUY KAKA Dieu de la guerre connu sous le nom du "destructeur de feu". AH CUN CAN Dieu de la guerre connu comme le "charmeur de serpents". AH KINCHIL Dieu solaire (voir Kinich Ahau). AHAU CHAMAHEZ Un des deux dieux de la médecine. AHMAKIQ Dieu de l'agriculture qui enferma le vent quand il menaçait de détruire les récoltes. AH MUNCEN CAB Dieu du miel et des abeilles sans dard; il est patron des apiculteurs. AH MUN Dieu du maïs et de la végétation. AH PEKU Dieu du Tonnerre. AH PUCH ou AH CIMI ou AH CIZIN Dieu de la Mort qui régnait sur le Metnal, le neuvième niveau de l'inframonde. AH RAXA LAC DMieu de lYa Terre.THOLOGICA.FR AH RAXA TZEL Dieu du ciel AH TABAI Dieu de la Chasse. AH UUC TICAB Dieu de la Terre. 1 AHAU CHAMAHEZ Dieu de la Médecine et de la Guérison. AHAU KIN voir Kinich Ahau. AHOACATI Dieu de la Fertilité AHTOLTECAT Dieu des orfèvres. -

Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts

Guide to Research at Hirsch Library Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts Before researching a work of art from the MFAH collection, the work should be viewed in the museum, if possible. The cultural context and descriptions of works in books and journals will be far more meaningful if you have taken advantage of this opportunity. Most good writing about art begins with careful inspections of the objects themselves, followed by informed library research. If the project includes the compiling of a bibliography, it will be most valuable if a full range of resources is consulted, including reference works, books, and journal articles. Listing on-line sources and survey books is usually much less informative. To find articles in scholarly journals, use indexes such as Art Abstracts or, the Bibliography of the History of Art. Exhibition catalogs and books about the holdings of other museums may contain entries written about related objects that could also provide guidance and examples of how to write about art. To find books, use keywords in the on-line catalog. Once relevant titles are located, careful attention to how those items are cataloged will lead to similar books with those subject headings. Footnotes and bibliographies in books and articles can also lead to other sources. University libraries will usually offer further holdings on a subject, and the Electronic Resources Room in the library can be used to access their on-line catalogs. Sylvan Barnet’s, A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 6th edition, provides a useful description of the process of looking, reading, and writing. -

From Folktale to Fantasy

From Folktale to Fantasy A Recipe-Based Approach to Creative Writing Michael Fox ABSTRACT In an environment of increasing strategies for creative writing “lessons” with varying degrees of constraints – ideas like the writing prompt, fash fction, and “uncreative” writing – one overlooked idea is to work with folktale types and motifs in order to create a story outline. Tis article sketches how such a lesson might be constructed, beginning with the selection of a tale type for the broad arc of the story, then moving to the range of individual motifs which might be available to populate that arc. Advanced students might further consider using the parallel and chiastic structures of folktale to sophisticate their outline. Te example used here – and suggested for use – is a folktale which informs both Beowulf and Te Hobbit and which, therefore, is likely at least to a certain extent to be familiar to many writers. Even if the outline which this exercise gen- erates were never used to write a full story, the process remains useful in thinking about the building blocks of story and traditional structures such as the archetypal “Hero’s Journey.” Writing in Practice 131 Introduction If the terms “motif” and “folktale” are unfamiliar, I am working with the following defnitions: a motif, I teach on the Writing side of a Department in terms of folklore, is “the smallest element in a tale of English and Writing Studies. I trained as a having a power to persist in tradition. In order to medievalist, but circumstances led me to a unit have this power, it must have something unusual and which teaches a range of courses from introductory striking about it” (Tompson 1977: 415). -

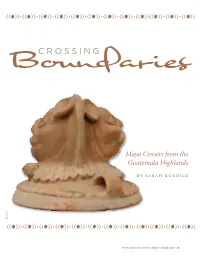

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

Hierarchy in the Representation of Death in Pre- and Post-Conquest Aztec Codices

1 Multilingual Discourses Vol. 1.2 Spring 2014 Tanya Ball The Power of Death: Hierarchy in the Representation of Death in Pre- and Post-Conquest Aztec Codices hrough an examination of Aztec death iconography in pre- and post-Conquest codices of the central valley of Mexico T (Borgia, Mendoza, Florentine, and Telleriano-Remensis), this paper will explore how attitudes towards the Aztec afterlife were linked to questions of hierarchical structure, ritual performance and the preservation of Aztec cosmovision. Particular attention will be paid to the representation of mummy bundles, sacrificial debt- payment and god-impersonator (ixiptla) sacrificial rituals. The scholarship of Alfredo López-Austin on Aztec world preservation through sacrifice will serve as a framework in this analysis of Aztec iconography on death. The transformation of pre-Hispanic traditions of representing death will be traced from these pre- to post-Conquest Mexican codices, in light of processes of guided syncretism as defined by Hugo G. Nutini and Diana Taylor’s work on the performative role that codices play in re-activating the past. These practices will help to reflect on the creation of the modern-day Mexican holiday of Día de los Muertos. Introduction An exploration of the representation of death in Mexica (popularly known as Aztec) pre- and post-Conquest Central Mexican codices is fascinating because it may reveal to us the persistence and transformation of Aztec attitudes towards death and the after-life, which in some cases still persist today in the Mexican holiday Día de Tanya Ball 2 los Muertos, or Day of the Dead. This tradition, which hails back to pre-Columbian times, occurs every November 1st and 2nd to coincide with All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ day in the Christian calendar, and honours the spirits of the deceased. -

The Mayan Gods: an Explanation from the Structures of Thought

Journal of Historical Archaeology & Anthropological Sciences Review Article Open Access The Mayan gods: an explanation from the structures of thought Abstract Volume 3 Issue 1 - 2018 This article explains the existence of the Classic and Post-classic Mayan gods through Laura Ibarra García the cognitive structure through which the Maya perceived and interpreted their world. Universidad de Guadalajara, Mexico This structure is none other than that built by every member of the human species during its early ontogenesis to interact with the outer world: the structure of action. Correspondence: Laura Ibarra García, Centro Universitario When this scheme is applied to the world’s interpretation, the phenomena in it and de Ciencias Sociales, Mexico, Tel 523336404456, the world as a whole appears as manifestations of a force that lies behind or within Email [email protected] all of them and which are perceived similarly to human subjects. This scheme, which finds application in the Mayan worldview, helps to understand the personality and Received: August 30, 2017 | Published: February 09, 2018 character of figures such as the solar god, the rain god, the sky god, the jaguar god and the gods of Venus. The application of the cognitive schema as driving logic also helps to understand the Maya established relationships between some animals, such as the jaguar and the rattlesnake and the highest deities. The study is part of the pioneering work that seeks to integrate the study of cognition development throughout history to the understanding of the historical and cultural manifestations of our country, especially of the Pre-Hispanic cultures. -

Bftrkeley and LOS ANGELES 1945 SIERRA POPOLUCA FOLKLORE and BELIEFS

SIERRA POPOLUCA FOLKLORE AND BELIEFS BY GEORGE M. FOSTER UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS IN AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY Volume 42, No. 2, pp. 177-250 UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BFtRKELEY AND LOS ANGELES 1945 SIERRA POPOLUCA FOLKLORE AND BELIEFS BY GEORGE M. FOSTER UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES 1945 UNIvERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUJBLICATIONS IN AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY EDITORS (Los ANGELES): RALTPH L. BEALS, FRANEKLN FEARING, HARRY HOIJER Volume 42, No. 2, pp. 177-250 Submitted by editors September 30, 1943 Issued January 19, 1945 Price, 75 cents UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND Los ANGELES CALIFORNIA CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON, ENGLAND PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERIOA CONTENTS PAGE I. INTTRODUCTION ........................ .......................... 177 II. STORIIES 1. The Origin of Maize .................................................. 191 2. The Origin of Maize (Second Version) ....................... 196 3. Two Men Meet a Rayo .................................................. 196 4. Story of the Armadillo .................................................. 198 5. Why the Alligator Has No Tongue ......................... 199 6. How the Turkey Lost His Means of Defense . .................... 199 7. Origin of the Partridge .................................................. 199 8. Why Copal Is Burned for the Chanekos ....................... 200 9. An Encounter with Chanekos ............................................. 201 10. The Chaneko, The Man, His Mistress, -

Autochthonous Aryans? the Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts

Michael Witzel Harvard University Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts. INTRODUCTION §1. Terminology § 2. Texts § 3. Dates §4. Indo-Aryans in the RV §5. Irano-Aryans in the Avesta §6. The Indo-Iranians §7. An ''Aryan'' Race? §8. Immigration §9. Remembrance of immigration §10. Linguistic and cultural acculturation THE AUTOCHTHONOUS ARYAN THEORY § 11. The ''Aryan Invasion'' and the "Out of India" theories LANGUAGE §12. Vedic, Iranian and Indo-European §13. Absence of Indian influences in Indo-Iranian §14. Date of Indo-Aryan innovations §15. Absence of retroflexes in Iranian §16. Absence of 'Indian' words in Iranian §17. Indo-European words in Indo-Iranian; Indo-European archaisms vs. Indian innovations §18. Absence of Indian influence in Mitanni Indo-Aryan Summary: Linguistics CHRONOLOGY §19. Lack of agreement of the autochthonous theory with the historical evidence: dating of kings and teachers ARCHAEOLOGY __________________________________________ Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 7-3 (EJVS) 2001(1-115) Autochthonous Aryans? 2 §20. Archaeology and texts §21. RV and the Indus civilization: horses and chariots §22. Absence of towns in the RV §23. Absence of wheat and rice in the RV §24. RV class society and the Indus civilization §25. The Sarasvatī and dating of the RV and the Bråhmaas §26. Harappan fire rituals? §27. Cultural continuity: pottery and the Indus script VEDIC TEXTS AND SCIENCE §28. The ''astronomical code of the RV'' §29. Astronomy: the equinoxes in ŚB §30. Astronomy: Jyotia Vedåga and the