The Study on Regional Freight Corridor Development Based on Port and Rail Systems in Sub‐Saharan Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of the Effectiveness of Rail Concessions in the SADC Region

Technical Report: Review of the Effectiveness of Rail Concessions in the SADC Region Larry Phipps, Short-term Consultant Submitted by: AECOM Submitted to: USAID/Southern Africa Gaborone, Botswana March 2009 USAID Contract No. 690-M-00-04-00309-00 (GS 10F-0277P) P.O. Box 602090 ▲Unit 4, Lot 40 ▲ Gaborone Commerce Park ▲ Gaborone, Botswana ▲ Phone (267) 390 0884 ▲ Fax (267) 390 1027 E-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................. 4 2. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Background .......................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Objectives of Study .............................................................................................. 9 2.3 Study Methodology .............................................................................................. 9 2.4 Report Structure................................................................................................. 10 3. BEITBRIDGE BULAWAYO RAILWAY CONCESSION ............................................. 11 3.1 Objectives of Privatization .................................................................................. 11 3.2 Scope of Railway Privatization ........................................................................... 11 3.3 Mode of Privatization......................................................................................... -

Railways: Looking for Traffi C

Chapter11 Railways: Looking for Traffi c frican railroads have changed greatly stock. Moreover, various confl icts and wars in the past 30 years. Back in the 1980s, have rendered several rail sections unusable. A many railway systems carried a large As a result, some networks have closed and share of their country’s traffi c because road many others are in relatively poor condition, transport was poor or faced restrictive regu- with investment backlogs stretching back over lations, and rail customers were established many years. businesses locked into rail either through Few railways are able to generate signifi - physical connections or (if they were para- cant funds for investment. Other than for statals) through policies requiring them to use purely mineral lines, investment has usually a fellow parastatal. Since then, most national come from bilateral and multilateral donors. economies and national railways have been Almost all remaining passenger services fail liberalized. Coupled with the general improve- to cover their costs, and freight service tariffs ment in road infrastructure, liberalization has are constrained by road competition. More- led to strong intermodal competition. Today, over, as long as the railways are government few railways outside South Africa, other than operated, bureaucratic constraints and lack dedicated mineral lines, are essential to the of commercial incentives will prevent them functioning of the economy. from competing successfully. Since 1993, sev- Rail networks in Africa are disconnected, eral governments in Africa have responded by and many are in poor condition. Although concessioning their systems, often accompa- an extensive system based in southern Africa nied by a rehabilitation program funded by reaches as far as the Democratic Republic of international fi nancial institutions. -

“Maritime Transport in Africa: Challenges, Opportunities, and an Agenda for Future Research”

UNCTAD Ad Hoc Expert Meeting (Under the framework of the IAME Conference 2018) 11 September 2018, Mombasa, Kenya “Maritime Transport In Africa: Challenges, Opportunities, and an Agenda for Future Research” Opportunity and Growth Diagnostic of Maritime Transportation in the Eastern and Southern Africa By Professor Godius Kahyarara Economics Department With Assistantship of Debora Simon Geography Department University of Dar-es-Salaam, United Republic of Tanzania This expert paper is reproduced by the UNCTAD secretariat in the form and language in which it has been received. Page 1 The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the UNCTAD. OPPORTUNITY AND GROWTH DIAGNOSTIC OF MARITIME TRANSPORTATION IN THE EASTERN AND SOUTHERN AFRICA Professor Godius Kahyarara University of Dar-es-Salaam Economics Department With Assistantship of Debora Simon University of Dar-es-Salaam Geography Department SUMMARY This paper examines opportunities and undertakes growth diagnostics of maritime transportation in the Eastern and Southern Africa. To do so it adopts a ‘Growth Diagnostic ‘methodology proposed by Ricardo Hausman, Dani Rodrick and Andres Velasco (HRV) to identify constraints that impede development of the Maritime transport focusing on a wide range of aspects within transportation corridors that are most critical and binding constraints to development of maritime transportation. The paper also assesses existing opportunities for Maritime Transportation and proposes the best approach to rip such opportunities. Paper findings are that port inefficiency depicted by longer container dwell time, delays in vessel traffic clearance, lengthy documentation processing, lesser container per crane hour (with exception of South Africa) as one of the critical binding constraints. -

Tender Advert -Tc 1015-19/20

BOTSWANA RAILWAYS PUBLIC TENDER NOTICE ENGAGEMENT OF CONSULTANTS FOR THE EVALUATION OF BIDS FOR THE CONSULTANCY SERVICES TO CONDUCT A BANKABLE FEASIBILITY STUDY FOR THE TWO RAIL LINKS OF MOSETSE-KAZUNGULA-LIVINGSTONE AND MMAMABULA LEPHALALE-TC 1015-19/20 Telex or facsimile tender submissions will not be The Procuring Entity is Botswana Railways and considered. Zambia Railways Limited. One (1) original tender document marked Botswana Railways (BR) is a Government Enterprise ORIGINAL and Four (4) duplicate copies of the given a mandate as sole Rail operator since original Document marked copy in one sealed establishment in 1987 (BR Act 1986; Amended in envelope clearly marked: “Tender Reference No. 2004). The act was amended to allow BR to form TC 1015 19/20 ENGAGEMENT OF CONSULTANTS FOR Joint Ventures, Subsidiary companies and to THE EVALUATION OF BIDS FOR THE CONSULTANCY exploit other business opportunities. SERVICES TO CONDUCT A BANKABLE FEASIBILITY BR is mandated to provide transportation of goods STUDY FOR THE TWO RAIL LINKS OF MOSETSE- and passengers within Botswana, effi ciently, safely KAZUNGULA-LIVINGSTONE AND MMAMABULA- and cost-effectively, along sound commercial LEPHALALE” shall be delivered to: lines. The Supply Chain Manager Botswana Railways Zambia Railways Limited (ZRL) is a parastatal Head Quarters railway of Zambia mandated to operate both Along A1 Road passenger and freight trains by an Act of Parliament Mowana Ward Mahalapye, Botswana with company registration number 12780. It is a The name and address of the bidder should be public company with the Industrial Development clearly marked on the envelope. Corporation (IDC) as its sole shareholder. -

Results of Railway Privatization in Africa

36005 THE WORLD BANK GROUP WASHINGTON, D.C. TP-8 TRANSPORT PAPERS SEPTEMBER 2005 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Results of Railway Privatization in Africa Richard Bullock. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized TRANSPORT SECTOR BOARD RESULTS OF RAILWAY PRIVATIZATION IN AFRICA Richard Bullock TRANSPORT THE WORLD BANK SECTOR Washington, D.C. BOARD © 2005 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone 202-473-1000 Internet www/worldbank.org Published September 2005 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. This paper has been produced with the financial assistance of a grant from TRISP, a partnership between the UK Department for International Development and the World Bank, for learning and sharing of knowledge in the fields of transport and rural infrastructure services. To order additional copies of this publication, please send an e-mail to the Transport Help Desk [email protected] Transport publications are available on-line at http://www.worldbank.org/transport/ RESULTS OF RAILWAY PRIVATIZATION IN AFRICA iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface .................................................................................................................................v Author’s Note ...................................................................................................................... -

Port of Maputo, Mozambique

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Transport Evolution presents 13 - 14 May 2019 | Port of Maputo, Mozambique 25+ expert speakers, including: Osório Lucas Chief Executive Officer, Maputo Port Development Company Col. Andre Ciseau Secretary General, Port Management Association of Eastern & Southern Africa (PMAESA) Clive Smith Chief Executive Officer, Walvis Bay Corridor Group, Namibia Johny Smith Chief Executive Officer, TransNamib Holdings Limited, Namibia Boineelo Shubane Director Operations, Botswana Railways, Botswana Building the next generation of ports and rail in Mozambique Host Port Authority: Supported by: Member of: Organised by: Simultaneous conference translation in English and Portuguese will be provided Será disponibilizada tradução simultânea da conferência em Inglês e Português www.transportevolutionmz.com Welcome to the inaugural Mozambique Ports and Rail Evolution Forum Ports and railways are leading economic engines for Mozambique, providing access to import and export markets, driving local job creation, and unlocking opportunities for the development of the local blue economy. Hosted by Maputo Port Development Company, Mozambique Ports and Rail Evolution prepares the region’s ports and railways for the fourth industrial revolution. Day one of the extensive two-day conference will feature a high level keynote comprising of leading African ports and rail authorities and focus on advancing Intra-African trade. We then explore challenges, opportunities and solutions for improving regional integration and connectivity. Concluding the day, attendees will learn from local and international ports authorities and terminal operators about challenges and opportunities for ports development. Day two begins by looking at major commodities that are driving infrastructure development forward and what types of funding and investment opportunities are available. This is followed by a rail spotlight session where we will learn from local and international rail authorities and operators about maintenance and development projects. -

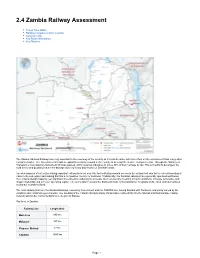

2.4 Zambia Railway Assessment

2.4 Zambia Railway Assessment Travel Time Matrix Railway Companies and Consortia Capacity Table Key Route Information Key Stations The Zambia National Railways are very important to the economy of the country as it is a bulk carrier with less effect on the environment than many other transport modes. The Government intends to expand its railway network in the country to develop the surface transport sector. Through the Ministry of Transport, a new statutory instrument (SI) was passed, which requires industries to move 30% of their carriage by rail. This is in a bid to decongest the road sector and possibly reduce the damage done by heavy duty trucks on Zambian roads. The development of rail routes linking important exit points is not only vital for facilitating smooth access to the outside but also for the overall boosting of trade in the sub-region and making Zambia a competitive country for business. Traditionally, the Zambian railways have generally operated well below their original design capacity, yet significant investment is underway to increase their volumes by investing in track conditions, increase locomotive and wagon availability and increase operating capital. The rail network remains the dominant mode of transportation for goods on the local and international routes but is under-utilized. The main railway lines are the Zambia Railways, owned by Government and the TAZARA line, linking Zambia with Tanzania, and jointly owned by the Zambian and Tanzanian governments. The opening of the Chipata-Mchinji railway link provides connectivity into the Malawi and Mozambique railway network and further connects Zambia to the port of Nacala. -

Botswana Country Mining Guide

KPMG GLOBAL MINING INSTITUTE Botswana Country mining guide kpmg.com/mining KPMG INTERNATIONAL Strategy Series B | Botswana mining guide © 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated. Contents Executive summary 2 New geographic expansion risk framework 3 Country snapshot 4 World Bank ranking: Ease of doing business 5 Type of government 6 Economy and fiscal policy 7 Heritage Foundation of Economic Freedom 8 Fraser Institute rankings 9 Sustainability and environment 12 Infrastructure development 17 Labor relations and employment situation 19 Inbound and outbound investment 19 Key commodities: Production and reserves 21 Major mining companies in Botswana 29 Foreign companies with operations in Botswana 29 © 2014 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”). KPMG International provides no client services and is a Swiss entity with which the independent member firms of the KPMG network are affiliated. 2 | Botswana mining guide Executive summary Since its independence in 1966, Botswana has witnessed good economic growth on the back of fiscal discipline and robust governance. The country has a strong legal framework, low prevalence of civil unrest or disorder and minimal government interference in the mining sector. Botswana also boasts infrastructure that is in better condition than several of its neighbors, which has assisted in boosting interest from international companies in the mining sector. Botswana is one of the world leaders in diamond production, with Russia competing closely. While Russia was the largest diamond producer in the world in terms of production volume in 2012, Botswana produced the most in terms of value, accounting for 23.6 percent of total global diamond production. -

Moving Away from Aid the Experience of Botswana Rachael Calleja and Annalisa Prizzon

Report Moving away from aid The experience of Botswana Rachael Calleja and Annalisa Prizzon December 2019 Readers are encouraged to reproduce material for their own publications, as long as these are not being sold commercially. ODI requests due acknowledgement and a copy of the publication. For online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the ODI website. The views presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of ODI or our partners. This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Cover photo: a pedestrian bridge in Gaborone, Botswana. Credit: Marc Shoul/Panos Pictures. Acknowledgements This report was possible only because of the generous financial contribution of Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), which partnered with the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) to explore the theme of country experiences towards graduation from official development assistance. Julie Kolsdorf (GIZ) brilliantly and effectively coordinated our preparation and follow-up between GIZ colleagues in Germany and in Gaborone, Botswana. Special thanks go to Tshepo Ketshabile (GIZ SADC office in Gaborone) for arranging and coordinating our schedule when we were in Botswana and for helping us to organise our trip. The GIZ SADC office in Gaborone, led by Thomas Schaef, and Fabian Kyrieleis at the German Embassy in Gaborone were instrumental to our fact-finding mission in Gaborone. Thanks also to Same Baaitse at the Ministry of International Affairs and International Development of the Government of Botswana who kindly and effectively scheduled our meetings with senior government officials. We are grateful for the editing of this report by Hannah Caddick. -

Botswana Transport & Infrastructure Statistics 2012

BOTSWANA TRANSPORT & INFRASTRUCTURE STATISTICS 2012 STATISTICS BOTSWANA Copyrights C Statistics Botswana 2013 Statistics Botswana. Private Bag 0024, Gaborone. Botswana Tel: (267) 367 1300. Fax: (267) 395 2201. Email: [email protected] Website: www.cso.gov.bw BOTSWANA TRANSPORT AND INFRASTRUCTURE STATISTICS - 2012 Published by Statistics Botswana Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Telephone: +267 367 1300 Fax: +267 395 6087 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cso.gov.bw Contact Unit: Transport and Infrastructure Statistics Unit Ministry of Transport and Communications November 2013 COPYRIGHT RESERVED No part of this information shall be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or even transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronically, mechanically, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Statistics Botswana TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE...........................................................................................................................................1 ABBREVIATIONS................................................................................................................................2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY......................................................................................................................3 1. INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................3 2. ROAD TRANSPORT......................................................................................................................3 -

National Transportation System in the Republic of Zambia

World Maritime University The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University World Maritime University Dissertations Dissertations 1990 National transportation system in the Republic of Zambia Febby Mtonga WMU Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Mtonga, Febby, "National transportation system in the Republic of Zambia" (1990). World Maritime University Dissertations. 877. https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/877 This Dissertation is brought to you courtesy of Maritime Commons. Open Access items may be downloaded for non- commercial, fair use academic purposes. No items may be hosted on another server or web site without express written permission from the World Maritime University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WMU LIBRARY WORLD MARITIME UNIVERSITY Malmo ~ Sweden THE NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM IN THE REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA by Febby Mtonga Zambia A paper submitted to the faculty of the World Maritime University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of a MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE in GENERAL MARITIME ADMINISTRATION The views and contents expressed in this paper reflect entirely those of my own and are not to be construed as necessarily endorsed by the University Signed: Date : 0 5 I 11 j S O Assessed by: Professor J. Mlynarcz] World Maritime University Ilf Co-assessed by: U. 2).i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PREFACE i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ii ABBREVIATIONS ... LIST OF MAPS AND APPENDICES iv CHAPTER 1 M • O • o Profile of the Republic of Zambia 1 1.1.0 Geographical Location of Zambia 1.2.0 Population 1.3.0 The Economy 1.3.1 Mining 1.3.2 Agriculture 3 1.3.3 Manufacturing 4 1.3.4 Transportation 7 1. -

Conference Brochure

CONFERENCE BROCHURE 13-14 June 2017 | Sandton Convention Centre | Johannesburg, South Africa Africa’s largest and only rail exhibition 100 Speakers| 7500 attendees | 850 VIP buyers | 250 exhibitors #africarail /africarail Created by: Visit www.terrapinn.com/africarail “It is a very informative conference and “Plenty of knowledge regarding African “This is a must attend event for the rail “Congratulations, one of the best and a good opportunity to network” railways is shared during the event.” industry!” most professional conferences outside Hlengiwe Sayd, Director, Department Of Transport Arvind Khare, Former CEO, Campanhia Dos Matthias Handschin, Business Development Europe!” Caminhos De Ferro Da Beira S.A.R.L. - C.C.F.B. Director, Alstom Christoph Uhl, VP Sales, Voith Turbo GmbH & Co KG “Its extremely informative and great place for networking“ Edwin Besa, Chief Director: Financial Analyst, Department of Public Enterprises – 2 – – 3 – OUR STORY AFRICA’S LONGEST RUNNING AND MOST SUCCESSFUL RAILWAYS EVENT NOW ENTERS ITS 20TH SUCCESSFUL YEAR. From humble beginnings as a small conference with a handful of exhibition stands, it now takes up 2 massive halls at the Sandton Convention Centre in Johannesburg. And has grown to become Africa’s most important and best supported railways conference and exhibition. For 2 decades, Africa Rail has become the undisputed leader. It is an unrivalled platform for the continent’s railways industry to come together … to learn, to network and to do business. Billions of dollars of business have either been initiated, Its where they open the doors to fantastic opportunities. concluded or influenced at this show. And it continues to Its where they form new and lucrative relationships & provide the meeting place for buyers, sellers and their partnerships.