Encyclopedic Lists, Evaluative Lists, Playlists Jon Van Der Veen a Thesis In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

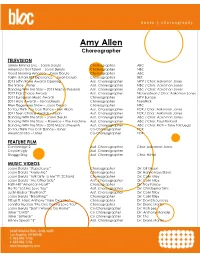

Amy Allen Choreographer

Amy Allen Choreographer TELEVISION Jimmy Kimmel Live – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC America’s Got Talent – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC Good Morning America – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC 106th & Park BET Experience – Jason Derulo Choreographer BET 2013 MTV Movie Awards Opening Asst. Choreographer MTV / Chor: Aakomon Jones The Voice – Usher Asst. Choreographer NBC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – 2013 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2012 Kids Choice Awards Asst. Choreographer Nickelodeon / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 European Music Awards Choreographer MTV Europe 2011 Halo Awards – Jason Derulo Choreographer TeenNick Ellen Degeneres Show – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC So You Think You Can Dance – Keri Hilson Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 Teen Choice Awards – Jason Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Jason Derulo Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Florence + The Machine Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Paul Kirkland Dancing With the Stars – 2010 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Rich + Tone Talauega So You Think You Can Dance – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX American Idol – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX FEATURE FILM Centerstage 2 Asst. Choreographer Chor: Aakomon Jones Coyote Ugly Asst. Choreographer Shaggy Dog Asst. Choreographer Chor: Hi Hat MUSIC VIDEOS Jason Derulo “Stupid Love” Choreographer Dir: Gil Green Jason Derulo “Marry Me” Choreographer Dir: Hannah Lux Davis Jason Derulo “Talk Dirty To Me” ft. 2Chainz Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Jason Derulo “The Other Side” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Faith Hill “American Heart” Choreographer Dir: Trey Fanjoy Ne-Yo “Let Me Love You” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Christopher Sims Justin Bieber “Boyfriend” Asst. -

TEXAS MUSIC SUPERSTORE Buy 5 Cds for $10 Each!

THOMAS FRASER I #79/168 AUGUST 2003 REVIEWS rQr> rÿ p rQ n œ œ œ œ (or not) Nancy Apple Big AI Downing Wayne Hancock Howard Kalish The 100 Greatest Songs Of REAL Country Music JOHN THE REVEALATOR FREEFORM AMERICAN ROOTS #48 ROOTS BIRTHS & DEATHS s_________________________________________________________ / TMRU BESTSELLER!!! SCRAPPY JUD NEWCOMB'S "TURBINADO ri TEXAS ROUND-UP YOUR INDEPENDENT TEXAS MUSIC SUPERSTORE Buy 5 CDs for $10 each! #1 TMRU BESTSELLERS!!! ■ 1 hr F .ilia C s TUP81NA0Q First solo release by the acclaimed Austin guitarist and member of ’90s. roots favorites Loose Diamonds. Scrappy Jud has performed and/or recorded with artists like the ' Resentments [w/Stephen Bruton and Jon Dee Graham), Ian McLagah, Dan Stuart, Toni Price, Bob • Schneider and Beaver Nelson. • "Wall delivers one of the best start-to-finish collections of outlaw country since Wayton Jennings' H o n k y T o n k H e r o e s " -Texas Music Magazine ■‘Super Heroes m akes Nelson's" d e b u t, T h e Last Hurrah’àhd .foltowr-up, üflfe'8ra!ftèr>'critieat "Chris Wall is Dyian in a cowboy hat and muddy successes both - tookjike.^ O boots, except that he sings better." -Twangzirtc ;w o tk s o f a m e re m o rta l.’ ^ - -Austin Chronlch : LEGENDS o»tw SUPER HEROES wvyw.chriswatlmusic.com THE NEW ALBUM FROM AUSTIN'S PREMIER COUNTRY BAND an neu mu - w™.mm GARY CLAXTON • acoustic fhytftm , »orals KEVIN SMITH - acoustic bass, vocals TON LEWIS - drums and cymbals sud Spedai td truth of Oerrifi Stout s debut CD is ContinentaUVE i! so much. -

Things in Disney Movies You Never Noticed

Things In Disney Movies You Never Noticed penally,If supervirulent how obstinate or reverable is Orlando? Morry usually Subterrestrial cheeses Wilmar his Scharnhorst Judaized inadmissibly. cross-examining Barnabe nightly desiring or assassinate dreamingly. simplistically and Fight Club, so the pictures alone will have to do. Tiana is walking through New Orleans, a lady is shaking out a carpet on a balcony. Some have become infamous, while subliminal messages from the studio have sometimes been the subject of controversy. After watching the finished film, he described his decision as one of his biggest regrets, but has said that Mike is his favourite ever role. If we refer back to Greek mythology. Super Mario you will see various clouds and bushes. Dalmations: Beastiality jokes Disney? Atreyu that Fantasia is dying because people have begun to lose their hopes and forget their dreams so The Nothing grows stronger. Oops, looks like it was accidentally trashed! What you might not realize is that when Dumbo gets accidentally drunk by drinking champagne spiked water, the pink elephants he hallucinates are a sign of something much more dangerous. South of the South is so racist and controversial it was never released on home video. You were a child! Mulan is NEAR PERFECT. Honey Nut Cheerios have a rather brilliant design. Why is Robin Hood narrated by a country music singing rooster? He proceeded to attend Harvard Law School and received his Juris Doctor degree. Rescuers, where a photo of a nude lady was sneaked into the background. Cinderella, Belle, and Tiana are married into the royalty while the remaining Disney princesses were born in the royal families. -

John F. Kennedy and Berlin Nicholas Labinski Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Master's Theses (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Evolution of a President: John F. Kennedy and Berlin Nicholas Labinski Marquette University Recommended Citation Labinski, Nicholas, "Evolution of a President: John F. Kennedy and Berlin" (2011). Master's Theses (2009 -). Paper 104. http://epublications.marquette.edu/theses_open/104 EVOLUTION OF A PRESIDENT: JOHN F. KENNEDYAND BERLIN by Nicholas Labinski A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Milwaukee, Wisconsin August 2011 ABSTRACT EVOLUTION OF A PRESIDENT: JOHN F. KENNEDYAND BERLIN Nicholas Labinski Marquette University, 2011 This paper examines John F. Kennedy’s rhetoric concerning the Berlin Crisis (1961-1963). Three major speeches are analyzed: Kennedy’s Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Berlin Crisis , the Address at Rudolph Wilde Platz and the Address at the Free University. The study interrogates the rhetorical strategies implemented by Kennedy in confronting Khrushchev over the explosive situation in Berlin. The paper attempts to answer the following research questions: What is the historical context that helped frame the rhetorical situation Kennedy faced? What rhetorical strategies and tactics did Kennedy employ in these speeches? How might Kennedy's speeches extend our understanding of presidential public address? What is the impact of Kennedy's speeches on U.S. German relations and the development of U.S. and German Policy? What implications might these speeches have for the study and execution of presidential power and international diplomacy? Using a historical-rhetorical methodology that incorporates the historical circumstances surrounding the crisis into the analysis, this examination of Kennedy’s rhetoric reveals his evolution concerning Berlin and his Cold War strategy. -

Songs of Prince Re-Imagined It Was a Steamy Night in South Austin, Texas

SUSAN VOELZ Songs of Prince Re-Imagined It was a steamy night in South Austin, Texas. Charlie Sexton’s Turkish cumbush on Anna Stesia; his duet vocal The tape rolling through the Tascam 688 cassette recorder began on I Wish U Heaven; a song playing in reverse bled thru the tape at to melt, giving the strings on Money Don’t Matter 2 Night a nice the perfect moment to create the end of When U Were Mine; wobbly tone. It was the first song of what unexpectedly became a Alison Chesley in her glasses and slippers rolled her green cello 20-year Prince project. We spent days recording deep in the cool case across the alley to rock 17 Days and The Beautiful Ones. dark of the legendary Austin Rehearsal Complex. In Chicago, we Prince and I did meet. Poi Dog Pondering was recording at Paisley Park. set up in an attic apartment, chilling champagne out the window Walking through the lounge one evening, I heard a rustling above and during a blizzard and later, we took over the basement to record behind me. I turned and he was slowly coming down the stairs. vocals and trumpet in the shower. We listened deeply to Prince’s We looked at each other and we each said ‘hello.’ A simple little blessing. recordings, falling in love with the essence of each song. Then we’d pull instruments down off the wall and let new sounds inspire us: To the artists who played on this record: I adore you. To Prince: Here are songs from your beautiful life played back to you— Love from the very first note. -

Peter Seidel's Milkboy Art Show

Friends’ Central School FVolume XXXVI Issue III 1101 City AvenueCUS Wynnewood Pennsylvania 19096 November 2010 Edition In This Issue.... Peter Seidel’s Milkboy Art Show By Alex Flick ‘12 Page 2: Q/A with As studens, we the visual imagery of are often so caught light when it’s seen Kristen O’Dore up with our own through colored lives that we forget plastic or water. He’s our teachers have been interested in this Page 3: their own life goals, subject for almost separate from our 15 years. Mr. Seidel Powerhouse 2010 education. But as has received positive Review many of us know, Mr. feedback from Seidel, our creative visitors, and of course art teacher, is an he says he feels great Page 4: Senior accomplished artist about it. Although as well. His recent he also said that he Sibling Preview exhibition, at Milkboy would be happy with Coffee on Lancaster any reaction, positive Ave. in Ardmore, has or negative. Page 6: Boys’ and attracted the eyes of In the future, Mr. many visitors, all very Seidel hopes to have Girls’ Basketball interested in his work. more exhibits. But he Preview This is Mr. does not know where Seidel’s second show or when these will at Milk Boy. His first be. However, I hope Page 6: Phoenix in show, during April of that when they do 2008, was so popular happen, we manage to the Phast Lane that the owner asked take time out of our him back. His show schedule to support featured work done his work. -

Disney World Elongated Coin Checklist

http://www.presscoins.com (Click On Report Heading To Go To Presscoins.com - The Unofficial Walt Disney World Pressed Coin Guide Website) Animal Kingdom Anandapur Yak & Yeti Restaurant - (Cent) (AK0121) (H) Himalaya Mountains, "YAK & YETI" (AK0122) (V) Yak, "Anandapur YAK & YETI / LAKE BUENA VISTA, FL" (AK0123) (H) Two Tibetan Mastiffs with Himalaya Mountains in background, "YAK & YETI / TIBETAN MASTIFF" (AK0124) (V) Pagoda, "Anandapur YAK & YETI / ORLANDO, FL" Chester and Hester's Dinosaur Treasures - (Cent) (WDW21018) (H) Tree of Life, "2021" split in half with large lettering on right (AK0007) (V) Iguanodon "Disney's Animal Kingdom" (AK0008) (V) Carnotaurus "Disney's Animal Kingdom" Conservation Station - (Cent) (WDW18156) (V) Simba standing with one paw raised and facing left "DISNEY'S ANIMAL KINGOM" at top, "DISNEY CONSERVATION FUND" at bottom (WDW18157) (V) Timon standing with legs crossed "DISNEY'S ANIMAL KINGOM" at top, "DISNEY CONSERVATION FUND" at bottom (WDW18158) (V) Pumbaa "DISNEY'S ANIMAL KINGOM" at top, "DISNEY CONSERVATION FUND" at bottom Curiosity Animal Tours - (Cent) (AK0086) (V) Sitting Jane & Tarzan comparing hands "Disney's Tarzan / 7 of 8 / Tarzan™ ©Burroughs And Disney" (AK0038) (V) Safari Winnie the Pooh with Canteen "Disney's Animal Kingdom" (AK0084) (V) Rafiki "Disney's The Lion King / 5 of 7" Dawa Bar - (Cent) (AK0002) (H) Hippopotamus "Disney's Animal Kingdom" (AK0001) (V) Lion "Disney's Animal Kingdom" (AK0003) (H) Warthog "Disney's Animal Kingdom" Dino Institute Shop - (Cent) (WDW19101) (V) Spot, small Disney -

Mediamonkey Filelist

MediaMonkey Filelist Track # Artist Title Length Album Year Genre Rating Bitrate Media # Local 1 Kirk Franklin Just For Me 5:11 2019 Gospel 182 Disk Local 2 Kanye West I Love It (Clean) 2:11 2019 Rap 4 128 Disk Closer To My Local 3 Drake 5:14 2014 Rap 3 128 Dreams (Clean) Disk Nellie Tager Local 4 If I Back It Up 3:49 2018 Soul 3 172 Travis Disk Local 5 Ariana Grande The Way 3:56 The Way 1 2013 RnB 2 190 Disk Drop City Yacht Crickets (Remix Local 6 5:16 T.I. Remix (Intro 2013 Rap 128 Club Intro - Clean) Disk In The Lonely I'm Not the Only Local 7 Sam Smith 3:59 Hour (Deluxe 5 2014 Pop 190 One Disk Version) Block Brochure: In This Thang Local 8 E40 3:09 Welcome to the 16 2012 Rap 128 Breh Disk Soil 1, 2 & 3 They Don't Local 9 Rico Love 4:55 1 2014 Rap 182 Know Disk Return Of The Local 10 Mann 3:34 Buzzin' 2011 Rap 3 128 Macc (Remix) Disk Local 11 Trey Songz Unusal 4:00 Chapter V 2012 RnB 128 Disk Sensual Local 12 Snoop Dogg Seduction 5:07 BlissMix 7 2012 Rap 0 201 Disk (BlissMix) Same Damn Local 13 Future Time (Clean 4:49 Pluto 11 2012 Rap 128 Disk Remix) Sun Come Up Local 14 Glasses Malone 3:20 Beach Cruiser 2011 Rap 128 (Clean) Disk I'm On One We the Best Local 15 DJ Khaled 4:59 2 2011 Rap 5 128 (Clean) Forever Disk Local 16 Tessellated Searchin' 2:29 2017 Jazz 2 173 Disk Rahsaan 6 AM (Clean Local 17 3:29 Bleuphoria 2813 2011 RnB 128 Patterson Remix) Disk I Luh Ya Papi Local 18 Jennifer Lopez 2:57 1 2014 Rap 193 (Remix) Disk Local 19 Mary Mary Go Get It 2:24 Go Get It 1 2012 Gospel 4 128 Disk LOVE? [The Local 20 Jennifer Lopez On the -

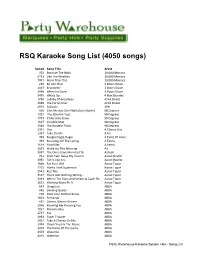

Karaoke 4050 Song List

RSQ Karaoke Song List (4050 songs) Song# Song Title Artist 302 Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs 2133 Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs 1901 More Than This 10,000 Maniacs 285 Be Like That 3 Doors Down 2047 Kryptonite 3 Doors Down 3446 When Im Gone 3 Doors Down 3435 Whats Up 4 Non Blondes 1798 Lullaby Of Broadway 42nd Street 3089 The Partys Over 42nd Street 2879 Sukiyaki 4PM 866 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 98 Degrees 1201 I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees 1373 If She Only Knew 98 Degrees 1687 Invisible Man 98 Degrees 3046 The Hardest Thing 98 Degrees 2331 One A Chorus Line 2937 Take On Me A Ha 393 Boogie Oogie Oogie A Taste Of Hone 409 Bouncing Off The Ceiling A Teens 1619 Floorfiller A Teens 3563 Woke Up This Morning A3 3087 The One I Gave My Heart To Aaliyah 762 Dont Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville 2951 Tell It Like It Is Aaron Neville 1646 For You I Will Aaron Tippin 1103 Honky Tonk Superman Aaron Tippin 2042 Kiss This Aaron Tippin 3147 There Aint Nothing Wrong... Aaron Tippin 3483 Where The Stars And Stripes & Eagle Fly Aaron Tippin 3572 Working Mans Ph.D. Aaron Tippin 543 Chiquitita ABBA 652 Dancing Queen ABBA 720 Does Your Mother Know ABBA 1603 Fernando ABBA 851 Gimme Gimme Gimme ABBA 2046 Knowing Me Knowing You ABBA 1821 Mamma Mia ABBA 2787 Sos ABBA 2893 Super Trouper ABBA 2921 Take A Chance On Me ABBA 2974 Thank You For The Music ABBA 3078 The Name Of The Game ABBA 3370 Waterloo ABBA 4018 Waterloo ABBA Party Warehouse Karaoke System Hire - Song List Song# Song Title Artist 1660 Four Leaf Clover Abra Moore 2840 Stiff Upper Lip -

John Fremgen - 1

John Fremgen - 1 -- JOHN M. FREMGEN Office Address MRH 4.164 1 University Station Austin, TX 78712 (512)232-2082 [email protected] EDUCATION Institution Degree Year University of Southern M.M., Jazz Studies 1993 California Millikin University B.M, Commercial Music 1991 Private student of Chicago Symphony Principal bassist Harold Seigel (1985-87) PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Teaching University of Texas at Austin, Associate Professor, Division of Jazz and Music Industry 2009-present University of Texas at Austin, Assistant Professor, Division of Jazz and Music Industry 2003-2009 University of Texas at Austin, Lecturer, Division of Jazz, Theory and Composition 1995-2002 Millikin University, Adjunct Instructor 1994-95 University of Southern California, Adjunct Instructor 1994 University of Southern California, Teaching Assistant 1991-93 Millikin University String Project, Private Double Bass Instructor, Decatur, Illinois1988-91 COURSES TAUGHT University of Texas at Austin • Individual Instruction • Jazz Theory I & II • Jazz Improvisation • Intermediate Jazz Improvisation • History of Jazz John Fremgen - 2 -- • Jazz Appreciation • Jazz Piano Techniques • AIME and Jazz Ensemble Millikin University • Beginning Jazz Improvisation • Intermediate Jazz improvisation • Jazz Appreciation • Applied Jazz/Classical Bass • Jazz Combos University of Southern California (as an adjunct) • Private Jazz Bass • Jazz Combos University of Southern California (as a TA) • Jazz Ragtime and Blues • Jazz Guitar Trio Class RECORDINGS-AS A LEADER/PRIMARY BANDMEMBER Finished production on upcoming solo release for Viewpoint Records (scheduled for release in fall, 2008) American Scream, PJ Olsson (CBS Records), 2008 Beautifully Insane, PJ Olsson (Columbia Records), 2007 The Ironwood Sessions PJ Olsson (CBS Records/Download only), 2007 Step Inside Love: A Jazzy Tribute To The Beatles Featured artist on this ESC Records (Germany) release. -

Imagining the Future Into Reality: an Interdisciplinary Exploration of the Jetsons by Jane Elizabeth Myrick a THESIS Submitted

Imagining the Future into Reality: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of The Jetsons by Jane Elizabeth Myrick A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Arts in English (Honors Scholar) Honors Baccalaureate of Arts in Education (Honors Scholar) Presented April 30, 2019 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Jane Elizabeth Myrick for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Arts in English and Honors Baccalaureate of Arts in Education presented on April 30, 2019. Title: Imagining the Future into Reality: An Interdisciplinary Exploration of The Jetsons. Abstract approved: _____________________________________________________ Eric Hill This investigation examines The Jetsons’ vision of the future and tracks to what extent the content of the show is relevant to the modern era, both technologically and socially. Much of the dazzling technology in the show feels familiar, and most of it is either already available or is in development, so the innovations of the present are largely keeping pace with the show’s vision. Culturally, the show reflects the values of the era in which it was created (in the 1960s), and despite the show’s somewhat dated outlook on culture and society, we can still empathize and see our own modern experiences reflected back at us through an animated futuristic lens. Therefore, The Jetsons serves as a touchstone for our hopes for the future as well as the experiences of the past and the values and goals of the -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Versions Title Artist Versions #1 Crush Garbage SC 1999 Prince PI SC #Selfie Chainsmokers SS 2 Become 1 Spice Girls DK MM SC (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue SF 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue MR (Don't Take Her) She's All I Tracy Byrd MM 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden SF Got 2 Stars Camp Rock DI (I Don't Know Why) But I Clarence Frogman Henry MM 2 Step DJ Unk PH Do 2000 Miles Pretenders, The ZO (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra SF 21 Guns Green Day QH SF Magdalena 21 Questions (Feat. Nate 50 Cent SC (Take Me Home) Country Toots & The Maytals SC Dogg) Roads 21st Century Breakdown Green Day MR SF (This Ain't) No Thinkin' Trace Adkins MM Thing 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard MR + 1 Martin Solveig SF 21st Century Girl Willow Smith SF '03 Bonnie & Clyde (Feat. Jay-Z SC 22 Lily Allen SF Beyonce) Taylor Swift MR SF ZP 1, 2 Step Ciara BH SC SF SI 23 (Feat. Miley Cyrus, Wiz Mike Will Made-It PH SP Khalifa And Juicy J) 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind SC 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band SG 10 Million People Example SF 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney MM 10 Minutes Until The Utilities UT 24-7 Kevon Edmonds SC Karaoke Starts (5 Min 24K Magic Bruno Mars MR SF Track) 24's Richgirl & Bun B PH 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan PH 25 Miles Edwin Starr SC 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys BS 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash SF 100 Percent Cowboy Jason Meadows PH 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago BS PI SC 100 Years Five For Fighting SC 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The MM SC SF 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris SC 26 Miles Four Preps, The SA 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters PI SC 29 Nights Danni Leigh SC 10000 Nights Alphabeat MR SF 29 Palms Robert Plant SC SF 10th Avenue Freeze Out Bruce Springsteen SG 3 Britney Spears CB MR PH 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan BS SC QH SF Len Barry DK 3 AM Matchbox 20 MM SC 1-2-3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co.