Burns and His Visitors from Ulster: from Adulation to Disaccord John Gray

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republican SINN FÉIN Poblachtach Theobald Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, County Kildare

Republican SINN FÉIN Poblachtach Theobald Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, County Kildare 2000 ‘Former Republicans have been bought off with palliatives’ Cathleen Knowles McGuirk, Vice President Republican Sinn Féin delivered the oration at the grave of Theobald Wolfe Tone, the founder of Irish Republicanism, on Sunday, June 11 in Bodenstown cemetery, outside Sallins, Co Kildare. The large crowd, led by a colour party carrying the National Flag and contingents of Cumann na mBan and Na Fianna Éireann, as well as the General Tom Maguire Flute Band from Belfast marched the three miles from Sallins Village to the grave of Wolfe Tone at Bodenstown. Contingents from all over Ireland as well as visitors from Britain and the United States took part in the march, which was marshalled by Seán Ó Sé, Dublin. At the graveside of Wolfe Tone the proceedings were chaired by Seán Mac Oscair, Fermanagh, Ard Chomhairle, Republican Sinn Féin who said he was delighted to see the large number of young people from all over Ireland in attendance this year. The ceremony was also addressed by Peig Galligan on behalf of the National Graves Association, who care for Ireland’s patriot graves. Róisín Hayden read a message from Republican Sinn Féin Patron, George Harrison, New York. Republican SINN FÉIN Poblachtach Theobald Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, County Kildare “A chairde, a comrádaithe agus a Phoblactánaigh, tá an-bhród orm agus tá sé d’onóir orm a bheith anseo inniu ag uaigh Thiobóid Wolfe Tone, Athair an Phoblachtachais in Éirinn. Fellow Republicans, once more we gather here in Bodenstown churchyard at the grave of Theobald Wolfe Tone, the greatest of the Republican leaders of the 18th century, the most visionary Irishman of his day, and regarded as the “Father of Irish Republicanism”. -

APRIL 2020 I Was Hungry and You Gave Me Something to Eat Matthew 25:35

APRIL 2020 I was hungry and you gave me something to eat Matthew 25:35 Barnabas stands alongside our Christian brothers and sisters around the world where they suffer discrimination and persecution. By providing aid through our Christian partners on the ground, we are able to maintain our overheads at less than 12% of our income. Please help us to help those who desperately need relief from their suffering. Barnabas Fund Donate online at: is a company Office 113, Russell Business Centre, registered in England 40-42 Lisburn Road, Belfast BT9 6AA www.barnabasaid.org/herald Number 04029536. Registered Charity [email protected] call: 07875 539003 Number 1092935 CONTENTS | APRIL 2020 FEATURES 12 Shaping young leaders The PCI Intern Scheme 16 Clubbing together A story from Bray Presbyterian 18 He is risen An Easter reflection 20 A steep learning curve A story from PCI’s Leaders in Training scheme 22 A shocking home truth New resource on tackling homelessness 34 Strengthening your pastoral core Advice for elders on Bible use 36 Equipping young people as everyday disciples A shocking home truth p22 Prioritising discipleship for young people 38 A San Francisco story Interview with a Presbyterian minister in California 40 Debating the persecution of Christians Report on House of Commons discussion REGULARS A San Francisco story p38 Debating the persecution of Christians p40 4 Letters 6 General news CONTRIBUTORS 8 In this month… Suzanne Hamilton is Tom Finnegan is the Senior Communications Training Development 9 My story Assistant for the Herald. Officer for PCI. In this role 11 Talking points She attends Ballyholme Tom develops and delivers Presbyterian in Bangor, training and resources for 14 Life lessons is married to Steven and congregational life and 15 Andrew Conway mum to twin boys. -

Domain-Specific Pseudonymous Signatures Revisited

Domain-Specific Pseudonymous Signatures Revisited Kamil Kluczniak Wroclaw University of Technology, Department of Computer Science [email protected] Abstract. Domain-Specific Pseudonymous Signature schemes were re- cently proposed for privacy preserving authentication of digital identity documents by the BSI, German Federal Office for Information Secu- rity. The crucial property of domain-specific pseudonymous signatures is that a signer may derive unique pseudonyms within a so called domain. Now, the signer's true identity is hidden behind his domain pseudonyms and these pseudonyms are unlinkable, i.e. it is infeasible to correlate two pseudonyms from distinct domains with the identity of a single signer. In this paper we take a critical look at the security definitions and construc- tions of domain-specific pseudonymous signatures proposed by far. We review two articles which propose \sound and clean" security definitions and point out some issues present in these models. Some of the issues we present may have a strong practical impact on constructions \provably secure" in this models. Additionally, we point out some worrisome facts about the proposed schemes and their security analysis. Key words: eID Documents, Privacy, Domain Signatures, Pseudonymity, Security Definition, Provable Security 1 Introduction Domain signature schemes are signature schemes where we have a set of users, an issuer and a set of domains. Each user obtains his secret keys in collaboration with the issuer and then may sign data with regards to his pseudonym. The crucial property of domain signatures is that each user may derive a pseudonym within a domain. Domain pseudonyms of a user are constant within a domain and a user should be unable to change his pseudonym within a domain, however, he may derive unique pseudonyms in each domain of the system. -

Irish Historical Studies

Reviews and short notices 141 war did not distract from undertaking revisions of the statute law or from providing legisla- tive remedies for private petitioners’ (pp xxx–xxxi). In their introduction, the editors provide insight into the proceedings of James’s parliament. They also address the possible content of missing public and private legislation, including: ‘an act for the speedy recovering of ser- vants’ wages’ (c. 23); ‘an act for reversal of the attainder of William Ryan of Bally Ryan in the county of Tipperary, esquire’ (c. 35); and ‘an act for relieving Dame Anna Yolanda Sarracourt alias Duval and her daughter’ (c. 33) (pp xxxvi–xli). In doing so, they shine a light on the lesser-known concerns of the 1689 parliament and on aspects of life and society at an important juncture in Ireland’s history. Bergin and Lyall provide a clear overview of their editorial method and the text of acts is pre- sented in a considered and accessible manner. The use of footnotes to highlight variations in the titles and text of different editions and lists of the acts is effective, while the appendices provide a helpful overview of surviving black-letter editions, the monthly tax rate imposed on individual counties, and a breakdown of the entries in the act of attainder by category and district, among other things. The indexes are comprehensive, making for an easily navigated volume. Overall, the editors have produced a highly important volume which further underlines the significance of the Irish Manuscripts Commission in preserving and disseminating primary sources relating to Ireland’s history and culture. -

Towards Formal Definitions

Covid Notions: Towards Formal Definitions – and Documented Understanding – of Privacy Goals and Claimed Protection in Proximity-Tracing Services Christiane Kuhn∗, Martin Becky, Thorsten Strufe∗z ∗ KIT Karlsruhe, fchristiane.kuhn, [email protected] y Huawei, [email protected] z Centre for Tactile Internet / TU Dresden April 17, 2020 Abstract—The recent SARS-CoV-2 pandemic gave rise to they are at risk, if they have been in proximity with another management approaches using mobile apps for contact tracing. individual that later tested positive for the disease), their The corresponding apps track individuals and their interactions, architecture (most protocols assume a server to participate in to facilitate alerting users of potential infections well before they become infectious themselves. Na¨ıve implementation obviously the service provision, c.f. PEPP-PT, [1], [2], [8]), and broadly jeopardizes the privacy of health conditions, location, activities, the fact that they assume some adversaries to aim at extracting and social interaction of its users. A number of protocol designs personal information from the service (sometimes also trolls for colocation tracking have already been developed, most of who could abuse, or try to sabotage the service or its users3). which claim to function in a privacy preserving manner. How- Most, if not all published proposals claim privacy, ever, despite claims such as “GDPR compliance”, “anonymity”, “pseudonymity” or other forms of “privacy”, the authors of these anonymity, or compliance with some data protection regu- designs usually neglect to precisely define what they (aim to) lations. However, none, to the best of our knowledge, has protect. actually formally defined threats, trust assumptions and ad- We make a first step towards formally defining the privacy versaries, or concrete protection goals. -

Relational-Cultural Perspectives of African American Women with Diabetes and Maintaining Multiple Roles

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses November 2017 Relational-Cultural Perspectives of African American Women with Diabetes and Maintaining Multiple Roles Ayesha Ali University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Other Nursing Commons Recommended Citation Ali, Ayesha, "Relational-Cultural Perspectives of African American Women with Diabetes and Maintaining Multiple Roles" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 1042. https://doi.org/10.7275/10586793.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1042 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Relational-Cultural Perspectives of African American Women with Diabetes and Maintaining Multiple Roles A Dissertation Presented by Ayesha Ali Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 2017 College of Nursing © Copyright by Ayesha Ali 2017 All Rights Reserved RELATIONAL-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN WITH DIABETES AND MAINTAINING MULTIPLE ROLES A Dissertation Presented By AYESHA ALI Approved as to style and content by: ________________________________________ Cynthia S. Jacelon, Chair ________________________________________ Genevieve E. Chandler, Member ________________________________________ Alexandrina Deschamps, Member ______________________________ Stephen Cavanagh, Dean College of Nursing DEDICATION This is dedicated to my mother and my always supportive husband. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to give a heart-felt thanks to my advisor and chair of my dissertation committee, Cynthia Jacelon. -

A Signature Scheme with Unlinkable-Yet-Acountable Pseudonymity for Privacy-Preserving Crowdsensing

A Signature Scheme with Unlinkable-yet-Acountable Pseudonymity for Privacy-Preserving Crowdsensing Victor Sucasas, IEEE Member; Georgios Mantas, IEEE Member; Joaquim Bastos; Francisco Damia˜o; Jonathan Rodriguez, IEEE Senior Member Abstract—Crowdsensing requires scalable privacy-preserving Smart City and crowdsensing participants. From the Smart City authentication that allows users to send anonymously sensing perspective the security concern is twofold. Firstly, sensors reports, while enabling eventual anonymity revocation in case are distributed and carried be citizens who could be malicious of user misbehavior. Previous research efforts already provide users sensing fake data or honest users with defective sensors. efficient mechanisms that enable conditional privacy through Secondly, citizens are rewarded for contributing to the sensing pseudonym systems, either based on Public Key Infrastructure tasks, and hence selfish users could submit their reports several (PKI) or Group Signature (GS) schemes. However, previous schemes do not enable users to self-generate an unlimited number times to increase their profits. From the citizens’ perspective of pseudonyms per user to enable users to participate in diverse the main concern is the location privacy, since crowdsensing sensing tasks simultaneously, while preventing the users from participants submit sensing data together with geolocation participating in the same task under different pseudonyms, which information [7]. Thus the Smart City can identify and locate is referred to as sybil attack. This paper addresses this issue by citizens, which can discourage citizens from participating in providing a scalable privacy-preserving authentication solution the sensing tasks [8],[9],[10]. for crowdsensing, based on a novel pseudonym-based signature scheme that enables unlinkable-yet-accountable pseudonymity. -

Travelling with Translink

Belfast Bus Map - Metro Services Showing High Frequency Corridors within the Metro Network Monkstown Main Corridors within Metro Network 1E Roughfort Milewater 1D Mossley Monkstown (Devenish Drive) Road From every From every Drive 5-10 mins 15-30 mins Carnmoney / Fairview Ballyhenry 2C/D/E 2C/D/E/G Jordanstown 1 Antrim Road Ballyearl Road 1A/C Road 2 Shore Road Drive 1B 14/A/B/C 13/A/B/C 3 Holywood Road Travelling with 13C, 14C 1A/C 2G New Manse 2A/B 1A/C Monkstown Forthill 13/A/B Avenue 4 Upper Newtownards Rd Mossley Way Drive 13B Circular Road 5 Castlereagh Road 2C/D/E 14B 1B/C/D/G Manse 2B Carnmoney Ballyduff 6 Cregagh Road Road Road Station Hydepark Doagh Ormeau Road Road Road 7 14/A/B/C 2H 8 Malone Road 13/A/B/C Cloughfern 2A Rathfern 9 Lisburn Road Translink 13C, 14C 1G 14A Ballyhenry 10 Falls Road Road 1B/C/D Derrycoole East 2D/E/H 14/C Antrim 11 Shankill Road 13/A/B/C Northcott Institute Rathmore 12 Oldpark Road Shopping 2B Carnmoney Drive 13/C 13A 14/A/B/C Centre Road A guide to using passenger transport in Northern Ireland 1B/C Doagh Sandyknowes 1A 16 Other Routes 1D Road 2C Antrim Terminus P Park & Ride 13 City Express 1E Road Glengormley 2E/H 1F 1B/C/F/G 13/A/B y Single direction routes indicated by arrows 13C, 14C M2 Motorway 1E/J 2A/B a w Church Braden r Inbound Outbound Circular Route o Road Park t o Mallusk Bellevue 2D M 1J 14/A/B Industrial M2 Estate Royal Abbey- M5 Mo 1F Mail 1E/J torwcentre 64 Belfast Zoo 2A/B 2B 14/A/C Blackrock Hightown a 2B/D Square y 64 Arthur 13C Belfast Castle Road 12C Whitewell 13/A/B 2B/C/D/E/G/H -

Topographical Index

997 TOPOGRAPHICAL INDEX EUROPE Penberthy Croft, St. Hilary: carminite, beudantite, 431 Iceland (fsland) Pengenna (Trewethen) mine, St. Kew: Bondolfur, East Iceland: pitchsbone, beudantite, carminite, mimetite, sco- oligoclase, 587 rodite, 432 Sellatur, East Iceland: pitchs~one, anor- Redruth: danalite, 921 thoclase, 587 Roscommon Cliff, St. Just-in-Peuwith: Skruthur, East Iceland: pitchstonc, stokesite, 433 anorthoclase, 587 St. Day: cornubite, 1 Thingmuli, East Iceland: andesine, 587 Treburland mine, Altarnun: genthelvite, molybdenite, 921 Faroes (F~eroerne) Treore mine, St. Teath: beudantite, carminite, jamesonite, mimetite, sco- Erionite, chabazite, 343 rodite, stibnite, 431 Tretoil mine, Lanivet: danalite, garnet, Norway (Norge) ilvaite, 921 Gryting, Risor: fergusonite (var. risSrite), Wheal Betsy, Tremore, Lanivet: he]vine, 392 scheelite, 921 Helle, Arendal: fergusonite, 392 Wheal Carpenter, Gwinear: beudantite, Nedends: fergusonite, 392 bayldonite, carminite, 431 ; cornubite, Rullandsdalen, Risor: fergusonite, 392 cornwallite, 1 Wheal Clinton, Mylor, Falmouth: danal- British Isles ire, 921 Wheal Cock, St. Just-in- Penwith : apatite, E~GLA~D i~D WALES bertrandite, herderite, helvine, phena- Adamite, hiibnerite, xliv kite, scheelite, 921 Billingham anhydrite mine, Durham: Wheal Ding (part of Bodmin Wheal aph~hitalite(?), arsenopyrite(?), ep- Mary): blende, he]vine, scheelite, 921 somite, ferric sulphate(?), gypsum, Wheal Gorland, Gwennap: cornubite, l; halite, ilsemannite(?), lepidocrocite, beudantite, carminite, zeunerite, 430 molybdenite(?), -

Workers Party Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, Co Kildare 27 June 2021

Workers Party Wolfe Tone Commemoration Bodenstown, Co Kildare 27 June 2021 Delivered by Workers Party and Central Executive Committee member Gerry Lynch (Dublin) 2021 marks the 230th anniversary of the founding of the United Irishmen by Wolfe Tone, Thomas Russell, Samuel Neilson, and others who set about revolutionising Irish society by breaking the power of the aristocracy and the established church. They aimed to instead establish a government genuinely representative of the people, and truly secular. But their ambitions did not simply stop at bringing about political change. The United Irishmen were social as well as political revolutionaries. They sought to overturn a society based on birth and privilege, and to build one where all citizens were equal. In place of a society dominated by the values of monarchy, aristocracy, and religion, they fought to create a republican society where everyone was free; where labour was respected and rewarded; where secularism replaced sectarianism; and where the power of the elite had been smashed and replaced by the power of the people. It was Jemmy Hope’s settled opinion “that the condition of the labouring class was the fundamental question at issue between the rulers and the people …” The United Irishmen were therefore political and social revolutionaries from their very foundation. This was true of them just as much as when they sought to achieve their aims peacefully by seeking sweeping reforms and raising the political consciousness of the masses through education, agitation, and organisation, as when they sought to achieve their aims by armed revolution in alliance with Revolutionary France. -

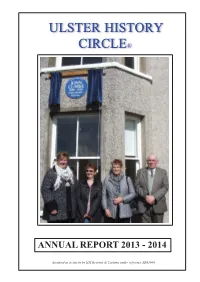

Annual Report 2013-2014

® $118$/5(3257 $FFHSWHGDVDFKDULW\E\+05HYHQXH &XVWRPVXQGHUUHIHUHQFH;5 ULSTER HISTORY CIRCLE ® ANNUAL REPORT 2013 - 2014 8/67(5+,6725<&,5&/( $118$/ 5(3257 Cover photograph: John Clarke plaque unveiling, 25 April 2013 Copyright © Ulster History Circle 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means; electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher. Published by the Ulster History Circle ULSTER HISTORY CIRCLE ® ANNUAL REPORT 2012 - 2013 :LOOLH-RKQ.HOO\EURWKHURI7KRPDV5D\PRQG.HOO\*&DQGPHPEHUVRIWKHZLGHU.HOO\IDPLO\ZLWK 5D\PRQG¶V*HRUJH&URVVDQG/OR\GV¶*DOODQWU\0HGDOVDIWHUXQYHLOLQJWKHSODTXHRQ'HFHPEHULQ 1HZU\ ULSTER HISTORY CIRCLE ® ANNUAL REPORT 2013 - 2014 Foreword The past year has seen a total of seventeen plaques erected by the Ulster History Circle, a significant increase on the nine of the previous year. These latest plaques are spread across Ulster, from Newry in the south east, to the north west in Co Donegal. Apart from our busy plaque activities, the Circle has been hard at work enhancing the New Dictionary of Ulster Biography. All our work is unpaid, and Circle members meet regularly in committee every month, as fundraising and planning the plaques are always on-going activities, with the summer months often busy with events. I would like to thank my colleagues on the Circle committee for their support and their valued contributions throughout the year. A voluntary body like ours depends entirely on the continuing commitment of its committee members. On behalf of the Circle I would also like to record how much we appreciate the generosity of our funders: many of the City and District Councils, and those individuals, organisations, and businesses without whose help and support the Circle could not continue in its work commemorating and celebrating the many distinguished people from, or significantly connected with, Ulster, who are exemplified by those remembered this year. -

Register of Employers

REGISTER OF EMPLOYERS A Register of Concerns in which people are employed in accordance with Article 47 of the Fair Employment and Treatment (Northern Ireland) Order 1998 The Equality Commission for Northern Ireland Equality House 7-9 Shaftesbury Square Belfast BT2 7DP Tel: (02890) 500 600 Fax: (02890) 328 970 Textphone: (02890) 500 589 E-mail [email protected] SEPTEMBER 2003 ________________________________________________REGISTRATION The Register Under Article 47 of the Fair Employment and Treatment (Northern Ireland) Order 1998 the Commission has a duty to keep a Register of those concerns employing more than 10 people in Northern Ireland and to make the information contained in the Register available for inspection by members of the public. The Register is available for use by the public in the Commission’s office. Under the legislation, public authorities as specified by the Office of the First Minister and the Deputy First Minister are automatically treated as registered with the Commission. All other employers have a duty to register if they have more than 10 employees working 16 hours or more per week. Employers who meet the conditions for registration are given one month in which to apply for registration. This month begins from the end of the week in which the concern employed more than 10 employees in Northern Ireland. It is a criminal offence for such an employer not to apply for registration within this period. Persons who become employers in relation to a registered concern are also under a legal duty to apply to have their name and address entered on the Register within one month of becoming such an employer.