The Series Helpmate: a Test of Imagination for the Practical Player by Robert Pye

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sally Matthews Is Magnificent

` DVORAK Rusalka, Glyndebourne Festival, Robin Ticciati. DVD Opus Arte Sally Matthews is magnificent. During the Act II court ball her moral and social confusion is palpable. And her sorrowful return to the lake in the last act to be reviled by her water sprite sisters would melt the winter ice. Christopher Cook, BBC Music Magazine, November 2020 Sally Matthews’ Rusalka is sung with a smoky soprano that has surprising heft given its delicacy, and the Prince is Evan LeRoy Johnson, who combines an ardent tenor with good looks. They have great chemistry between them and the whole cast is excellent. Opera Now, November-December 2020 SCHUMANN Paradies und die Peri, Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Paolo Bortolameolli Matthews is noted for her interpretation of the demanding role of the Peri and also appears on one of its few recordings, with Rattle conducting. The soprano was richly communicative in the taxing vocal lines, which called for frequent leaps and a culminating high C … Her most rewarding moments occurred in Part III, particularly in “Verstossen, verschlossen” (“Expelled again”), as she fervently Sally Matthews vowed to go to the depths of the earth, an operatic tour-de-force. Janelle Gelfand, Cincinnati Business Courier, December 2019 Soprano BARBER Two Scenes from Anthony & Cleopatra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Juanjo Mena This critic had heard a fine performance of this music by Matthews and Mena at the BBC Proms in London in 2018, but their performance here on Thursday was even finer. Looking suitably regal in a glittery gold form-fitting gown, the British soprano put her full, vibrant, richly contoured voice fully at the service of text and music. -

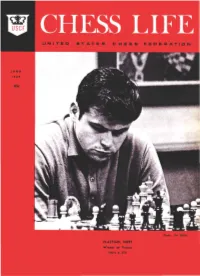

CHESS FEDERATION Newburgh, N.Y

Announcing an important new series of books on CONTEMPORARY CHESS OPENINGS Published by Chess Digest, Inc.-General Editor, R. G. Wade The first book in this current series is a fresh look at 's I IAN by Leonard Borden, William Hartston, and Raymond Keene Two of the most brilliant young ployers pool their talents with one of the world's well-established authorities on openings to produce a modern, definitive study of the King's Indian Defence. An essen tial work of reference which will help master and amateur alike to win more games. The King's Indian Defence has established itself as one of the most lively and populor openings and this book provides 0 systematic description of its strategy, tactics, and variations. Written to provide instruction and under standing, it contains well-chosen illustrative games from octuol ploy, many of them shown to the very lost move, and each with an analysis of its salient features. An excellent cloth-bound book in English Descriptive Notation, with cleor type, good diagrams, and an easy-to-follow format. The highest quality at a very reasonable price. Postpaid, only $4.40 DON'T WAIT-ORDER NOW-THE BOOK YOU MUST HAVE! FLA NINGS by Raymond Keene Raymond Keene, brightest star in the rising galaxy of young British players, was undefeated in the 1968 British Championship and in the 1968 Olympiad at Lugano. In this book, he posses along to you the benefit of his studies of the King's Indian Attack and the Reti, Catalan, English, and Benko Larsen openings. The notation is Algebraic, the notes comprehensive but easily understood and right to the point. -

Chess & Bridge

2013 Catalogue Chess & Bridge Plus Backgammon Poker and other traditional games cbcat2013_p02_contents_Layout 1 02/11/2012 09:18 Page 1 Contents CONTENTS WAYS TO ORDER Chess Section Call our Order Line 3-9 Wooden Chess Sets 10-11 Wooden Chess Boards 020 7288 1305 or 12 Chess Boxes 13 Chess Tables 020 7486 7015 14-17 Wooden Chess Combinations 9.30am-6pm Monday - Saturday 18 Miscellaneous Sets 11am - 5pm Sundays 19 Decorative & Themed Chess Sets 20-21 Travel Sets 22 Giant Chess Sets Shop online 23-25 Chess Clocks www.chess.co.uk/shop 26-28 Plastic Chess Sets & Combinations or 29 Demonstration Chess Boards www.bridgeshop.com 30-31 Stationery, Medals & Trophies 32 Chess T-Shirts 33-37 Chess DVDs Post the order form to: 38-39 Chess Software: Playing Programs 40 Chess Software: ChessBase 12` Chess & Bridge 41-43 Chess Software: Fritz Media System 44 Baker Street 44-45 Chess Software: from Chess Assistant 46 Recommendations for Junior Players London, W1U 7RT 47 Subscribe to Chess Magazine 48-49 Order Form 50 Subscribe to BRIDGE Magazine REASONS TO SHOP ONLINE 51 Recommendations for Junior Players - New items added each and every week 52-55 Chess Computers - Many more items online 56-60 Bargain Chess Books 61-66 Chess Books - Larger and alternative images for most items - Full descriptions of each item Bridge Section - Exclusive website offers on selected items 68 Bridge Tables & Cloths 69-70 Bridge Equipment - Pay securely via Debit/Credit Card or PayPal 71-72 Bridge Software: Playing Programs 73 Bridge Software: Instructional 74-77 Decorative Playing Cards 78-83 Gift Ideas & Bridge DVDs 84-86 Bargain Bridge Books 87 Recommended Bridge Books 88-89 Bridge Books by Subject 90-91 Backgammon 92 Go 93 Poker 94 Other Games 95 Website Information 96 Retail shop information page 2 TO ORDER 020 7288 1305 or 020 7486 7015 cbcat2013_p03to5_woodsets_Layout 1 02/11/2012 09:53 Page 1 Wooden Chess Sets A LITTLE MORE INFORMATION ABOUT OUR CHESS SETS.. -

PHILIDOR in AUSTRALIA & AMERICA

PHILIDOR in AUSTRALIA & AMERICA. Chapter 1 - Philidor’s games in his 1749 book-are they real? p. 4 Chapter 2 - Von der Lasa on the Games in Philidor’s 1749 book. p. 11 Chapter 3 - Australian Research-Chess World & c p. 20 Chapter 4 - American Research- Chess Monthly & c p. 49 Chapter 5 - Bibliography of Philidor’s books from the US Chess Monthly. p. 60 Continuation of American Research p. 67 Chapter 6 - Philidor’s Games from OECG & Boffa p. 98 Part 2 Chapter 7 - Francois Andre Danican Philidor Websites p. 102 Chapter 8 - Philidor’s Social Network and Timeline and Musical works p. 120 Chapter 9 - Philidor in Historical Fiction p. 146. Chapter 10- When did Philidor go to Holland and England? p. 160 Chapter 11- A Chess Champion Whose Operas Pleased a King. p. 162 Chapter 12- Eighteenth Century extracts from Fiske’s 1859 book. p. 167 Chapter 13- Philidor The Master of Masters by Solomon Hecht. p. 178+ ‘The Gambit’ Sept. 1928 (Hecht from Ray Kuzanek) The Mystery of Philidor’s Declaration that the Pawns are The Soul of Chess. (Hecht ‘The Gambit’ Sept. 1930) p. 233+ Chapter 14- Lovers of Philidor. p. 198 Chapter 15- Who was Michael Sedaine? p. 200 Chapter 16- Philidor and Vaucanson p. 201 Chapter 17- Review of Sergio Boffa’s Philidor book (ca 2010) p. 202 Chapter 18- Criticism of Philidor by Ercole del Rio + Ponziani mini bio. p.204 Chapter 19- The Gainsborough Philidor? p.209 Chapter 20- Captain Smith – Philidor – Captain Smith p.210 1 PREFACE When David Lovejoy wrote to me about a novel on Philidor as his possible next project and would I help with research, I agreed. -

31 March 2017 Page 1 of 8

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 25 – 31 March 2017 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 25 MARCH 2017 roadside drama, which has him asking questions of Graham SAT 07:30 Yes Yes Yes (b00tcstj) Greene again.. Series 1, The Last Gasp Gold SAT 00:00 Stephen Baxter - Voyage (b007q9ld) Reader Paul Bazely John Rawling relives the 1991 World Athletics Championships 1985-86 Project Ares Producer Duncan Minshull. when Britain©s 400m men©s relay team beat the USA to gold. The first manned Mars mission blasts off on a perilous voyage of SAT 03:00 Charles Dickens - The Personal History of David SAT 08:00 Archive on 4 (b00kmhl4) discovery - both scientific and personal. Stars Laurel Lefkow. Copperfield (b007jmtp) Lynne Truss - Did I Really Ask That? SAT 00:30 Soul Music (b01mw2dj) Good and Bad Angels Lynne Truss shares her personal treasure trove of interviews with Series 14, Bach©s St Matthew Passion David falls in love, and questions his friendship with Steerforth. world famous writers. Bach©s St Matthew Passion was written in 1727 and was probably Stars Miriam Margolyes, Sheila Hancock and Phil Daniels. Between 1980 and 1990, Lynne was a part-time arts journalist, first performed as part of the Good Friday Service at SAT 04:00 The 3rd Degree (b05vx4dx) meeting and interviewing many giants of the theatre, including Thomaskirche in Leipzig. This programme explores ways in Series 5, Aston University Arthur Miller, Tom Stoppard, Simon Gray, Athol Fugard and which Bach©s St Mattew Passion touches and changes people©s A quiz show hosted by Steve Punt where a team of three Anthony Minghella. -

Brekke the Chess Saga of Fridrik Olafsson

ØYSTEIN BREKKE | FRIDRIK ÓLAFSSON The Chess Saga of FRIÐRIK ÓLAFSSON with special contributions from Gudmundur G. Thórarinsson, Gunnar Finnlaugsson, Tiger Hillarp Persson, Axel Smith, Ian Rogers, Yasser Seirawan, Jan Timman, Margeir Pétursson and Jóhann Hjartarson NORSK SJAKKFORLAG TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword by President of Iceland, Guðni Th. Jóhannesson ..................4 Preface .........................................................5 Norsk Sjakkforlag Fridrik Ólafsson and his Achievements by Gudmundur G. Thorarinsson .....8 Øystein Brekke Haugesgate 84 A Chapter 1: 1946 – 54 From Childhood to Nordic Champion .............10 3019 Drammen, Norway Mail: [email protected] Chapter 2: 1955 – 57 National Hero and International Master ...........42 Tlf. +47 32 82 10 64 / +47 91 18 91 90 www.sjakkforlag.no Chapter 3: 1958 – 59 A World Championship Candidate at 23 ..........64 www.sjakkbutikken.no Chapter 4: 1960 – 62 Missed Qualification in the 1962 Interzonal ........94 ISBN 978-82-90779-28-8 Chapter 5: 1963 – 68 From Los Angeles to Reykjavik ..................114 Authors: Øystein Brekke & Fridrik Ólafsson Chapter 6: 1969 – 73 The World’s Strongest Amateur Player ............134 Design: Tommy Modøl & Øystein Brekke Proof-reading: Tony Gillam & Hakon Adler Chapter 7: 1974 – 76 Hunting New Tournament Victories ..............166 Front page photo: Chapter 8: 1977 – 82 Brilliant Games & President of FIDE ..............206 Fridrik in the Beverwijk tournament 1961. (Harry Pot, Nationaal Archief) Chapter 9: 1983 – 99 Fridrik and the Golden Era of Icelandic Chess ....246 Production: XIDE AS & Norsk Sjakkforlag Chapter 10: 2000 – An Honorary Veteran Still Attacking ..............262 Cover: XIDE AS & Norsk Sjakkforlag Printing and binding: XIDE AS Games in the Book ................................................282 Paper: Multiart Silk 115 gram Opening index ....................................................284 Copyright © 2021 by Norsk Sjakkforlag / Øystein Brekke Index of opponents, photos and illustrations ...........................285 All rights reserved. -

CHESS OPENINGS Published by Chess Digest, Inc.-General Editor, R

Announcing an important new series of books on CONTEMPORARY CHESS OPENINGS Published by Chess Digest, Inc.-General Editor, R. G. Wade The first book in this current series is a fresh look at THE '$ INDIAN DEF by Leonard Barden, William Hartston, and Raymond Keene Two of the most brilliant young players pool their talents with one of the world's well-established authorities on openings to produce a modern, definitive study of the King's Indian Defence. An essen tial work of reference which will help master and amateur alike to win more games. The King's Indian Defence has established itself as one of the most lively and popular openings and this book provides 0 systematic description of its strategy, tactics, and variations. Written to provide instruction and under standing, it contains well-chosen illustrative games from actual play, many of them shown to the very last move, and each with an analysis of its salient features. An excellent cloth-bound book in English Descriptive Notation, with clear type, goad diagrams, and on easy-to-follow format. The highest quality at a very reasonable price. Postpaid, only $4.40 DON'T WAIT-ORDER NOW-THE BOOK YOU MUST HAVE! K OPEN by Raymond Keene Raymond Keene, brightest star in the rising galaxy of young British players, was undefeated in the 1968 British Championship and in the 1968 Olympiad at Lugano. In this book, he posses along to you the benefit of his studies of the King's Indian Attack and the Ret;, Catalan, English, and Benko Larsen openings. The notation is AlgebraiC, the notes comprehensive but easily understood and right to the point. -

Atlantic Books

ATLANTIC BOOKS JULY – DECEMBER 2021 Contents Recent Highlights 2 Atlantic Books: Fiction 5 Atlantic Books: Non-Fiction 9 Corvus 33 Grove Press 47 Allen & Unwin: Fiction 55 Allen & Unwin: Non-Fiction 59 Allen & Unwin Australia: Distribution Titles 71 Export: Key Editions 77 Sales, Publicity & Rights 78 Index 81 Bestselling Backlist 86 Recent Highlights Atlantic’s bestselling and critically acclaimed titles from the past twelve months. The Cat and The The Girl from The Mystery of City Widow Hills Charles Dickens Nick Bradley Megan Miranda A.N. Wilson 9781786499912 • Paperback • 9781838950750 • Paperback • 9781786497932 • Paperback • £8.99 £8.99 £9.99 The Natural The New Class The Nothing Health Service War Man Isabel Hardman Michael Lind Catherine Ryan Howard 9781786495921 • Paperback • 9781786499578 • Paperback • 9781786496614 • Paperback • £9.99 £8.99 £8.99 2 Open Parisian Lives Pilgrims Johan Norberg Deirdre Bair Matthew Kneale 9781786497192 • Paperback • 9781786492685 • Paperback • 9781786492395 • Paperback • £9.99 £10.99 £8.99 Three Little Why the Why We Can’t Truths Germans Do it Sleep Eithne Shortall Better Ada Calhoun 9781786496201 • Paperback • John Kampfner 9781611854664 • Paperback • £8.99 9781786499783 • Paperback • £8.99 £9.99 3 4 Atlantic Books Fiction Atlantic Fiction has a reputation for publishing bold, innovative writing from around the world. Our Autumn 2021 list includes a funny and original debut about the unintentional consequences of anxiety; a translated literary thriller about betrayal and murder in the global fertility market; and the paperback of Bryan Washington’s critically acclaimed debut Memorial. 5 *Stop Press* We Play Ourselves Jen Silverman Like a cross between Shelia Heti’s How Should A Person Be? and Lily King’s Writers & Lovers, this is a wildly entertaining debut novel of female rage, self-sabotage, the pursuit of fame and the costs of artistic ambition. -

It Goes on the Shelf 33 November 2011

It Goes On The Shelf 33 November 2011 It Goes On The Shelf 33 November 2011 1 It Goes On The Shelf 33 November 2011 It Goes On The Shelf Published at The Sign of the Purple Mouth by Ned Brooks 4817 Dean Lane, Lilburn GA 30047-4720 [email protected] Website - http://home.sprynet.com/~nedbrooks/home.htm "And departing, leave behind us Toothprints in the hands of time." Cover by Brad Foster, drawing by Steve Stiles, bacover by Dan Osterman Tarock Rules by A Nony Mouse, www.tarock.net, 24pp+card Strayed into a book stack here, only 2x4.5 inches, plus a heavy plastic card. Tarock is a complicated card game played with a 54-card Tarot deck, said to have been popular in Austria-Hungary before WWI. The daffynitions may have lost something in translation: Skeench-a-tola - When the players wish to end the, [sic] the dealer calls Skeench-a-tola. The cards are dealt and a Round is played as usual. Whoever ends up with the Skeench (the Joker) will be the last dealer of the game. If the Skeench ends up in the Talon, the next Round is Skeench-a-tola. The rest of it is even worse - I'll stick to Hearts. I have shelved it with the Tarot decks. Silent Type II, edited by Cynthia Lowry & Brandon MacInnis, Quirky Works Books October 2010, 60pp, illustrations, photos, wraps This was given me by Dale Speirs. In another place it is called "Issue #2" so it must be a magazine. All poetry and pictures, and I recognize one name from the typewriter collectors Yahoo-list. -

Chess-Books.Pdf

All books mentioned below are being given to you as a friend from our collection of New good condition books from the library of Dombivli Chess Academy since we believe in the promotion of the game of Chess & your request as a Chess lover. Free Home delivery anywhere in India Hindi Books 1. Vikarna par Kamjoriya - Chess Times Rs.100 2. Shatranj-Shah aur Maat - Sampurna Yudhniti by Shekhar Rs.200 Ebooks available at Rs.100. Email shipping 1. Chris Baker - A Startling Chess Opening Repertoire (1998) 2. Steffen Pedersen - The Dutch for the Attacking Player (1996) 3. Samisch Kings Indian Uncovered 4. Beim Valeri - Understanding.the.Leningrad.Dutch 5. 1001 Brilliant Chess Sacrifices 6. 303 Tricky Chess Tactic 7. Chess Tips For The Improving Player 8. John Nunn 's Chess Puzzle Book 9. Paul Keres, Alexander Kotov - The Art of the Middle Game 10. Tal, Fischer & Kasparov 11. The Magic of Chess Tactics 12. Vukovic Vladimir - The art of attack in chess 13. Troitzky - 360 Brilliant and Instructive Endgames 14. Yudovich - Garri Kasparov,1988 Books available at Rs.100 1. First Moves How To Start A Chess Game by David Pritchard 2. ABC’s of Chess - H.K.Tiwari 3. Bishop Endings - Chess Times 4. Diagonal Weakness - Chess Times 5. Seven is the Limit - Miniatur Chess Problems- Sikdar Books available at Rs.150 1. Mastering Checkmates 2. Chess Players Battle Manual - Nigel Davies 3. Zee Boom Bah - K Muralimohan 4. Chess Tactics - Paul Littlewood 5. Batsfords Chess Puzzles 6. Kamikaze - K.Muralimohan Books available at Rs.200 1. An opening Repertoire for White-Raymond Keene 2. -

![[Poswl.Ebook] Improve Your Chess (Teach Yourself) Pdf Free](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1604/poswl-ebook-improve-your-chess-teach-yourself-pdf-free-4761604.webp)

[Poswl.Ebook] Improve Your Chess (Teach Yourself) Pdf Free

poswl (Read download) Improve Your Chess (Teach Yourself) Online [poswl.ebook] Improve Your Chess (Teach Yourself) Pdf Free William Hartson DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #2532978 in Books Hartston Hartston William 2016-06-28 2016-06-28Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 7.75 x .50 x 5.00l, .40 #File Name: 1444103083166 pagesImprove Your Chess | File size: 44.Mb William Hartson : Improve Your Chess (Teach Yourself) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Improve Your Chess (Teach Yourself): 4 of 4 people found the following review helpful. Excellent, excellent, excellent!By Jack ReaderI am one of those players who, while being stuck at a USCF 1500 range for years, still believe that with a right book/help could turn into a higher rated player. So, I keep buying books that fill up a bookshelf, but causing more and more disappointment as well (and I am STILL stuck at a 1500 range). Playing more is clearly not the answer as the faulty thinking is not corrected. Coaching is expensive. Real help and improvement is hard to find.This book turned out to be one of those rare gems that immediately changed the way I look at a position. Packed with brief, but relevant and helpful mini- lessons, divided into "Basic"(1-25), "Advanced" (26-50) and "Mastery" (51-75) sections it can induce a paradigm shift quickly. It has framed rules like "Weak players assess a position by counting the captured men; strong players consider only the men remaining on the board", diagrams (here you will still need a board to play out the solution) and excellent discussions (the one about the "bad bishop" is eye opening) along with arguing the sense in robotic moves ("pawn to rook three", "bishop to knight's five"). -

Chess Promoters of Mumbai

Bhaarat Chess Manufacturers A Chess Promoters Group Enterprise A-Z Destination for Chess lovers – Quality guaranteed Export Quality Chess Sets, Game Timers, Chess Books, Chess software’s, Giant Garden Games & gift items Ø World’s finest quality Chess Set & Board game manufacturers Ø India’s only Giant garden games manufacturer Ø India’s leading providers of Chess Clocks & Chess Books Purchase our products online at www.indiachess.in 30% flat discount on MRP / 60% discount for whole sellers Free Delivery anywhere in the World within 3 days!!! All our products are designed to last a lifetime! Cash on Delivery is also available in India with delivery in 7 days at INR 200 extra or 10% extra whichever is higher!!! We invite you in Mumbai to have a look at all our products Bhaarat Chess Manufacturers is World’s foremost manufacturers of chess equipments & Giant Board Games. India is known for producing the finest quality Chess sets in the world. We have been serving the sports lovers from all over the world with the complete chess solutions. We cater to Chess lovers, Chess trainers, Chess Tournament organizers, schools, colleges, resorts, Builders & all those who love sports. We also organize Chess Tournaments & conduct Chess training seminars. We have our own Chess clubs & Chess training academies in Mumbai. We organize over 10 Chess events every year for the promotion of the game. Origin of the game of Chess Originated in India by the name Ashtapad, this ancient game has historical references in India where chess was used as a tool to teach military strategy to Indian princes.