Ex Acton Ad Astra the Golden Age of a Chancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Staysafe Welcome “I Wish It Need Not Have Happened in My Time,” Said Frodo

KESPIRIT #StaySafe Welcome “I wish it need not have happened in my time,” said Frodo. Thank “So do I,” said Gandalf, “and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for you to them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.” The Fellowship of the Ring, JRR Tolkien You can always trust an Old Edwardian to find the right words. everyone On Friday 20 March 2020, we held our last day in school for the remainder of the academic year. Here, just as everywhere, there was who is trepidation for the weeks ahead. Pupils and teachers went home laden with bags. No one knew how long we would be away from our desks, or what we would experience in the meantime. No one could predict how events would unfold, as we began what may be the Contents hardest days many of us will see in our lifetimes. PPE and medical supplies 4 But this was not the resounding tone of the day. Though there were keeping many things beyond our control, no one here on campus stood to dwell on the uncertainties. A can-do attitude swelled immediately. Science and academia 9 The leaving Sixth Form hurriedly completed all of their rites of passage before the doors closed. Staff launched an ‘online common Working on the frontline 13 room’ and created a rota for volunteering to look after those pupils who were to remain in school. People left the grounds offering their Responding to the pandemic 20 us support to one another, particularly those more adept with IT. -

ZUGZWANGS in CHESS STUDIES G.Mcc. Haworth,1 H.M.J.F. Van Der

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290629887 Zugzwangs in Chess Studies Article in ICGA journal · June 2011 DOI: 10.3233/ICG-2011-34205 CITATION READS 1 2,142 3 authors: Guy McCrossan Haworth Harold M.J.F. Van der Heijden University of Reading Gezondheidsdienst voor Dieren 119 PUBLICATIONS 354 CITATIONS 49 PUBLICATIONS 1,232 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Eiko Bleicher 7 PUBLICATIONS 12 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Chess Endgame Analysis View project The Skilloscopy project View project All content following this page was uploaded by Guy McCrossan Haworth on 23 January 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. 82 ICGA Journal June 2011 NOTES ZUGZWANGS IN CHESS STUDIES G.McC. Haworth,1 H.M.J.F. van der Heijden and E. Bleicher Reading, U.K., Deventer, the Netherlands and Berlin, Germany ABSTRACT Van der Heijden’s ENDGAME STUDY DATABASE IV, HHDBIV, is the definitive collection of 76,132 chess studies. The zugzwang position or zug, one in which the side to move would prefer not to, is a frequent theme in the literature of chess studies. In this third data-mining of HHDBIV, we report on the occurrence of sub-7-man zugs there as discovered by the use of CQL and Nalimov endgame tables (EGTs). We also mine those Zugzwang Studies in which a zug more significantly appears in both its White-to-move (wtm) and Black-to-move (btm) forms. We provide some illustrative and extreme examples of zugzwangs in studies. -

Taming Wild Chess Openings

Taming Wild Chess Openings How to deal with the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly over the chess board By International Master John Watson & FIDE Master Eric Schiller New In Chess 2015 1 Contents Explanation of Symbols ���������������������������������������������������������������� 8 Icons ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Introduction �������������������������������������������������������������������������� 10 BAD WHITE OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 18 Halloween Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♘c3 ♘f6 4.♘xe5 ♘xe5 5.d4 . 18 Grünfeld Defense: The Gibbon: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 g6 3.♘c3 d5 4.g4 . 20 Grob Attack: 1.g4 . 21 English Wing Gambit: 1.c4 c5 2.b4 . 25 French Defense: Orthoschnapp Gambit: 1.e4 e6 2.c4 d5 3.cxd5 exd5 4.♕b3 . 27 Benko Gambit: The Mutkin: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 c5 3.d5 b5 4.g4 . 28 Zilbermints - Benoni Gambit: 1.d4 c5 2.b4 . 29 Boden-Kieseritzky Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗c4 ♘f6 4.♘c3 ♘xe4 5.0-0 . 31 Drunken Hippo Formation: 1.a3 e5 2.b3 d5 3.c3 c5 4.d3 ♘c6 5.e3 ♘e7 6.f3 g6 7.g3 . 33 Kadas Opening: 1.h4 . 35 Cochrane Gambit 1: 5.♗c4 and 5.♘c3 . 37 Cochrane Gambit 2: 5.d4 Main Line: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘f6 3.♘xe5 d6 4.♘xf7 ♔xf7 5.d4 . 40 Nimzowitsch Defense: Wheeler Gambit: 1.e4 ♘c6 2.b4 . 43 BAD BLACK OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 44 Khan Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♗c4 d5 . 44 King’s Gambit: Nordwalde Variation: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♕f6 . 45 King’s Gambit: Sénéchaud Countergambit: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♗c5 3.♘f3 g5 . -

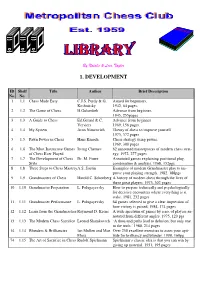

1. Development

By Natalie & Leon Taylor 1. DEVELOPMENT ID Shelf Title Author Brief Description No. No. 1 1.1 Chess Made Easy C.J.S. Purdy & G. Aimed for beginners, Koshnitsky 1942, 64 pages. 2 1.2 The Game of Chess H.Golombek Advance from beginner, 1945, 255pages 3 1.3 A Guide to Chess Ed.Gerard & C. Advance from beginner Verviers 1969, 156 pages. 4 1.4 My System Aron Nimzovich Theory of chess to improve yourself 1973, 372 pages 5 1.5 Pawn Power in Chess Hans Kmoch Chess strategy using pawns. 1969, 300 pages 6 1.6 The Most Instructive Games Irving Chernev 62 annotated masterpieces of modern chess strat- of Chess Ever Played egy. 1972, 277 pages 7 1.7 The Development of Chess Dr. M. Euwe Annotated games explaining positional play, Style combination & analysis. 1968, 152pgs 8 1.8 Three Steps to Chess MasteryA.S. Suetin Examples of modern Grandmaster play to im- prove your playing strength. 1982, 188pgs 9 1.9 Grandmasters of Chess Harold C. Schonberg A history of modern chess through the lives of these great players. 1973, 302 pages 10 1.10 Grandmaster Preparation L. Polugayevsky How to prepare technically and psychologically for decisive encounters where everything is at stake. 1981, 232 pages 11 1.11 Grandmaster Performance L. Polugayevsky 64 games selected to give a clear impression of how victory is gained. 1984, 174 pages 12 1.12 Learn from the Grandmasters Raymond D. Keene A wide spectrum of games by a no. of players an- notated from different angles. 1975, 120 pgs 13 1.13 The Modern Chess Sacrifice Leonid Shamkovich ‘A thousand paths lead to delusion, but only one to the truth.’ 1980, 214 pages 14 1.14 Blunders & Brilliancies Ian Mullen and Moe Over 250 excellent exercises to asses your apti- Moss tude for brilliancy and blunder. -

Mind-Bending Analysis and Instructive Comment from a Man Who Has Participated in World Chess at the Very Highest Levels

Mind-bending analysis and instructive comment from a man who has participated in world chess at the very highest levels World championship candidate and three-times British Champion Jon Speelman annotates the best of his games. He is renowned as a great fighter and analyst, and a highly original player. This book provides entertainment and instruction in abundance. Games and stories from his: • World Championship campaigns • Chess Olympiads • Toi>level grandmaster tournaments, including the World Cup Jon Speelman is one of only two British players this century to gain a place in the world's top five. He has reached the sem>finals of the world championship and is one of the stars of the English national team, which has won the silver medals three times in the chess Olympiads. Jon Speelman's Best Games Jon Speelman B. T. Batsford Ltd, London First published 1997 © Jon Speelman 1997 ISBN 0 7134 6477 I British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. Contents A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, by any means, without prior permission of the publisher. Introduction 5 Typeset and edited by First Rank Publishing, Brighton and printed in Great Britain by Redwood Books, Trowbridge, Wilts Part I Growing up as a Chess player for the publishers, B. T. Batsford Ltd, Juvenilia 7 583 Fulham Road, I JS-J.Fletcher, British U-14 Ch., Rhyl1969 9 London SW6 5BY 2 JS-E.Warren, Thames Valley Open 1970 11 3 A.Miles-JS, Islington Open 1970 14 4 JS-Hanau, Nice 1971 -

A New Look at the Tayler by David Kane

A New Look at the Tayler by David kane I: Introduction The Tayler Variation (aka the Tayler Opening) is a line that has been unjustly neglected, in my view. The line is of surprisingly recent vintage though it is often confused with the Inverted Hungarian (or Inverted Hanham Defense), a line which shares the same opening moves: 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Be2: The Inverted Hungarian is an old opening, dating back to the 1860ʼs, at least. Tartakower played it a few times in the 1920ʼs with mixed results, using the continuation, 3...Nf6 4. d3: a rather unenterprising setup for White. In 1981 British player, John Tayler (see biographical note), published an article in the British publication Chess (vol. 46) on a line he had developed stemming from the sharp 4. d4!?. This is a move which apparently no one had thought to play before, and one that transforms the sedate Inverted Hungarian into something else altogether. Technically, it is really the Tayler Variation to the Inverted Hungarian Defense rather than the Tayler Opening, though through usage, the terms are interchangeable for all practical purposes. As has been so often the case when it comes to unorthodox lines, I first heard of this opening via Mike Basman when he published a cassette on it back in the early 80ʼs (still available through audiochess.com). Tayler 2 The line stirred some interest at the time but gradually seems to have been forgotten. The final nail in the coffin was probably some light analysis published by Eric Schiller in Gambit Chess Openings (and elsewhere) where he dismisses the line primarily due to his loss in the game Schiller-Martinovsky, Chicago 1986. -

Sally Matthews Is Magnificent

` DVORAK Rusalka, Glyndebourne Festival, Robin Ticciati. DVD Opus Arte Sally Matthews is magnificent. During the Act II court ball her moral and social confusion is palpable. And her sorrowful return to the lake in the last act to be reviled by her water sprite sisters would melt the winter ice. Christopher Cook, BBC Music Magazine, November 2020 Sally Matthews’ Rusalka is sung with a smoky soprano that has surprising heft given its delicacy, and the Prince is Evan LeRoy Johnson, who combines an ardent tenor with good looks. They have great chemistry between them and the whole cast is excellent. Opera Now, November-December 2020 SCHUMANN Paradies und die Peri, Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Paolo Bortolameolli Matthews is noted for her interpretation of the demanding role of the Peri and also appears on one of its few recordings, with Rattle conducting. The soprano was richly communicative in the taxing vocal lines, which called for frequent leaps and a culminating high C … Her most rewarding moments occurred in Part III, particularly in “Verstossen, verschlossen” (“Expelled again”), as she fervently Sally Matthews vowed to go to the depths of the earth, an operatic tour-de-force. Janelle Gelfand, Cincinnati Business Courier, December 2019 Soprano BARBER Two Scenes from Anthony & Cleopatra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Juanjo Mena This critic had heard a fine performance of this music by Matthews and Mena at the BBC Proms in London in 2018, but their performance here on Thursday was even finer. Looking suitably regal in a glittery gold form-fitting gown, the British soprano put her full, vibrant, richly contoured voice fully at the service of text and music. -

1978 July 08

1ST ASIAN GRANDMASTERS CIRCUIT- 3RD ROUND RESULTS ~-~AY~R s I & I 7 · .Chess. 1 EUGENE TORRE (PHIL) GM ½I½ 2 MIGUEL QUINTEROS (ARG) A-sia·n _ ascendancy· 3 MERSHAD SHAR CHESS IN Indonesia is very were taken to a sports sta• popular, and not only at dium, one floor of which is AROUAH BACTIAR (IND) IM international levels. Indonesia · permanently reserved for 6 LUIS CHIONG (PHIL) has an advantage over other chess. There, were 400-500 . 7 O'KELLY DE GALWAY (BEL) GM countries because the game is people present, but also at 8 CRAIG LAIRD (NZ) indigenous to the people and least- as many cheering 9 KAMRAN SHIRAZ! (IRAN) has not been artificially "in-: school pupils outsiqe_ which traduced": · gave the . place q1}1te an 10 MURRAY CHANDLER (NZ)/. atmosphere. 11 ARDIANSYAH (IND) /M That was strikingly illus• trated during the third leg of After the ceremony a band· 12 JACOBUS SAMPOUW (IND) the 1st Asian Grandmaster's · struck - up while snacks and 13 CHRISTIE HON (MALAYSIA) Circuit when all the partici-: drinks were handed out. 14 HERMAN SURADIRADJA(IND) /, pants were invited to attend a Then, amid further cheering prizegiving of the teams and whistling, the reluctant IM NORM =8½ GM NORM=10 CATEGORY 5 championship in Jakarta. We participants _from the circuit. were called on stage to be in• 19. d4 c4 This timely advance puts 28. Nd5 good guys .. troduced, and Wt' were pre• 20. d5! Chiong in serious dif iculties. Planning to answer 28 . 33. Kh1 Ra? sented with pieces of the \;MIONG The way . -

57 New Year's Ride to the Normal

TTHHEE PPUUZZZZLLIINNGG SSIIDDEE OOFF CCHHEESSSS Jeff Coakley A NEW YEAR’S RIDE TO THE NORMAL SIDE number 57 December 28, 2013 For many players, the holiday season is associated with unusual chess problems. The Puzzling Side of Chess takes the opposite approach. To celebrate the end of each year, we cross over, for a brief moment in time, to “the normal side of chess”. As described in our first holiday column (21), normal chess means direct mates, endgame studies, and game positions. So here, for your New Year’s entertainment, is a selection of twelve standard problems. Cheers, everyone! Happy New Year from the Chess Cafe! Let’s begin our journey into the world of chess normalcy with a simple mate in two. Then we’ll gradually work our way up to the harder stuff. 1 w________w áwdwHkdwd] àdwIw)wdw] ßwdwdwGwd] Þdwdwdwdw] Ýwdwdwdwd] Üdwdwdwdw] Ûwdwdwdwd] Údwdw$wdw] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw White to mate in 2 Miniature problems, with seven pieces or less, have always been a favourite of mine, especially mates in two. Positions with eight to twelve pieces, like the one below, are known as merediths. The name honours American composer William Meredith (1835-1903) of Philadelphia. 2 w________w áwdkdwdwd] àdwdRdNHw] ßwdwdwdwd] ÞdPdwIwdw] ÝwdwdwdBd] ÜdwdwdwGw] Ûwdwdwdwd] Údwdwdwdw] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw White to mate in 2 In the first two puzzles, the only black piece was the king. Samuel Loyd, in his book Chess Strategy (1878), called such positions “intimidated king problems”. The black king is not intimidated in the next mate in two. In fact, the black forces outnumber the white. Sam Loyd had these two things to say about his composition: “This problem is especially constructed to give a deceptive appearance to mislead the solver ...” “To amateur solvers, .. -

CHESS FEDERATION Newburgh, N.Y

Announcing an important new series of books on CONTEMPORARY CHESS OPENINGS Published by Chess Digest, Inc.-General Editor, R. G. Wade The first book in this current series is a fresh look at 's I IAN by Leonard Borden, William Hartston, and Raymond Keene Two of the most brilliant young ployers pool their talents with one of the world's well-established authorities on openings to produce a modern, definitive study of the King's Indian Defence. An essen tial work of reference which will help master and amateur alike to win more games. The King's Indian Defence has established itself as one of the most lively and populor openings and this book provides 0 systematic description of its strategy, tactics, and variations. Written to provide instruction and under standing, it contains well-chosen illustrative games from octuol ploy, many of them shown to the very lost move, and each with an analysis of its salient features. An excellent cloth-bound book in English Descriptive Notation, with cleor type, good diagrams, and an easy-to-follow format. The highest quality at a very reasonable price. Postpaid, only $4.40 DON'T WAIT-ORDER NOW-THE BOOK YOU MUST HAVE! FLA NINGS by Raymond Keene Raymond Keene, brightest star in the rising galaxy of young British players, was undefeated in the 1968 British Championship and in the 1968 Olympiad at Lugano. In this book, he posses along to you the benefit of his studies of the King's Indian Attack and the Reti, Catalan, English, and Benko Larsen openings. The notation is Algebraic, the notes comprehensive but easily understood and right to the point. -

Formation Attack Strategies

Formation Attack Strategies Joel Johnson Edited by: Eric Hammond © Joel Johnson, June 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from Joel Johnson. Edited by: Eric Hammond Cover Photography: Barry M. Evans Cover Design: Joel Johnson Game Searching: Joel Johnson, Richard J. Cowan, William Parker Proofreading: Joel Johnson Game Contributors: Brian Wall, Jack Young, Clyde Nakamura, James Rizzitano, Keith Hayward, Hal Terrie, Richard Cowan, Jesús Seoane, William Parker, Domingos Perego Linares Diagram and Linares Figurine fonts ©1993-2003 by Alpine Electronics, Steve Smith Alpine Electronics 703 Ivinson Ave. Laramie, WY 82070 Email: Alpine Chess Fonts ([email protected]) Website: http://www.partae.com/fonts/ CONTENTS Preface 9 Kudos 9 Purpose of the Book 10 Harry Lyman 9 Education 10 Chess In The Schools 10 Chess Friendships and Sportsmanship 10 Eulogy for Harry Lyman (by Shelby Lyman) 10 Harry Lyman Games 10 Passing The Torch 9 Joshua Zhu 10 Richard Cowan 10 Matthew Miller 10 Luke Miller 10 Noah Raskin 10 Eric Hammond 10 Jimi Sullivan 10 Phil Terrill 10 Austin Terrill 10 Bailey Vidler 10 Clark Vidler 10 Michael Oldehoff 10 Bogdan Anghel 10 Jamie Aronson 10 Rich Desmarais 10 Nick Desmarais 10 Joe Range 10 Bernabe Garcia 10 Nancy Jones 10 Adam Nehmeh 10 Paul Nehmeh 10 Section A – Attack Philosophies 11 Personal Development 12 Frame of Mind 15 Dual Aspects of Chess 30 Chess Mechanics -

Chess Endgame News

Chess Endgame News Article Published Version Haworth, G. (2014) Chess Endgame News. ICGA Journal, 37 (3). pp. 166-168. ISSN 1389-6911 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/38987/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: The International Computer Games Association All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online 166 ICGA Journal September 2014 CHESS ENDGAME NEWS G.McC. Haworth1 Reading, UK This note investigates the recently revived proposal that the stalemated side should lose, and comments further on the information provided by the FRITZ14 interface to Ronald de Man’s DTZ50 endgame tables (EGTs). Tables 1 and 2 list relevant positions: data files (Haworth, 2014b) provide chess-line sources and annotation. Pos.w-b Endgame FEN Notes g1 3-2 KBPKP 8/5KBk/8/8/p7/P7/8/8 b - - 34 124 Korchnoi - Karpov, WCC.5 (1978) g2 3-3 KPPKPP 8/6p1/5p2/5P1K/4k2P/8/8/8 b - - 2 65 Anand - Kramnik, WCC.5 (2007) 65. … Kxf5 g3 3-2 KRKRB 5r2/8/8/8/8/3kb3/3R4/3K4 b - - 94 109 Carlsen - van Wely, Corus (2007) 109. … Bxd2 == g4 7-7 KQR..KQR.. 2Q5/5Rpk/8/1p2p2p/1P2Pn1P/5Pq1/4r3/7K w Evans - Reshevsky, USC (1963), 49.