PHILIDOR in AUSTRALIA & AMERICA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eingorn, Viacheslav

A Rock-Solid Chess Opening Repertoire for Black Viacheslav Eingorn First published in the UK by Gambit Publications Ltd 2012 Copyright © Viacheslav Eingom 2012 The right of Viacheslav Eingom to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordancewith the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No partof this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without prior permission of the publisher. In particular, no part of this publication may be scanned, transmitted via the Internet or uploaded to a website without the pub lisher's permission. Any personwho does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damage. ISBN-13: 978-1-906454-31-9 ISBN-10: 1-906454-31-0 DISTRIBUTION: Worldwide (except USA): Central Books Ltd, 99 Wallis Rd, London E9 5LN, England. Tel +44 (0)20 8986 4854 Fax +44 (0)20 8533 5821. E-mail: [email protected] Gambit Publications Ltd, 99 Wallis Rd, London E9 5LN, England. E-mail: [email protected] Website (regularly updated): www.gambitbooks.com Edited by Graham Burgess Typeset by Petra Nunn Cover image by WolffMorrow Printed in Great Britain by the MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King's Lynn 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Gambit Publications Ltd Managing Director: Murray Chandler GM Chess Director: Dr John Nunn GM Editorial Director: Graham Burgess FM GermanEditor: Petra Nunn -

Taming Wild Chess Openings

Taming Wild Chess Openings How to deal with the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly over the chess board By International Master John Watson & FIDE Master Eric Schiller New In Chess 2015 1 Contents Explanation of Symbols ���������������������������������������������������������������� 8 Icons ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Introduction �������������������������������������������������������������������������� 10 BAD WHITE OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 18 Halloween Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♘c3 ♘f6 4.♘xe5 ♘xe5 5.d4 . 18 Grünfeld Defense: The Gibbon: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 g6 3.♘c3 d5 4.g4 . 20 Grob Attack: 1.g4 . 21 English Wing Gambit: 1.c4 c5 2.b4 . 25 French Defense: Orthoschnapp Gambit: 1.e4 e6 2.c4 d5 3.cxd5 exd5 4.♕b3 . 27 Benko Gambit: The Mutkin: 1.d4 ♘f6 2.c4 c5 3.d5 b5 4.g4 . 28 Zilbermints - Benoni Gambit: 1.d4 c5 2.b4 . 29 Boden-Kieseritzky Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘c6 3.♗c4 ♘f6 4.♘c3 ♘xe4 5.0-0 . 31 Drunken Hippo Formation: 1.a3 e5 2.b3 d5 3.c3 c5 4.d3 ♘c6 5.e3 ♘e7 6.f3 g6 7.g3 . 33 Kadas Opening: 1.h4 . 35 Cochrane Gambit 1: 5.♗c4 and 5.♘c3 . 37 Cochrane Gambit 2: 5.d4 Main Line: 1.e4 e5 2.♘f3 ♘f6 3.♘xe5 d6 4.♘xf7 ♔xf7 5.d4 . 40 Nimzowitsch Defense: Wheeler Gambit: 1.e4 ♘c6 2.b4 . 43 BAD BLACK OPENINGS ��������������������������������������������������������������� 44 Khan Gambit: 1.e4 e5 2.♗c4 d5 . 44 King’s Gambit: Nordwalde Variation: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♕f6 . 45 King’s Gambit: Sénéchaud Countergambit: 1.e4 e5 2.f4 ♗c5 3.♘f3 g5 . -

Little Chess Evaluation Compendium by Lyudmil Tsvetkov, Sofia, Bulgaria

Little Chess Evaluation Compendium By Lyudmil Tsvetkov, Sofia, Bulgaria Version from 2012, an update to an original version first released in 2010 The purpose will be to give a fairly precise evaluation for all the most important terms. Some authors might find some interesting ideas. For abbreviations, p will mean pawns, cp – centipawns, if the number is not indicated it will be centipawns, mps - millipawns; b – bishop, n – knight, k- king, q – queen and r –rook. Also b will mean black and w – white. We will assume that the bishop value is 3ps, knight value – 3ps, rook value – 4.5 ps and queen value – 9ps. In brackets I will be giving purely speculative numbers for possible Elo increase if a specific function is implemented (only for the functions that might not be generally implemented). The exposition will be split in 3 parts, reflecting that opening, middlegame and endgame are very different from one another. The essence of chess in two words Chess is a game of capturing. This is the single most important thing worth considering. But in order to be able to capture well, you should consider a variety of other specific rules. The more rules you consider, the better you will be able to capture. If you consider 10 rules, you will be able to capture. If you consider 100 rules, you will be able to capture in a sufficiently good way. If you consider 1000 rules, you will be able to capture in an excellent way. The philosophy of chess Chess is a game of correlation, and not a game of fixed values. -

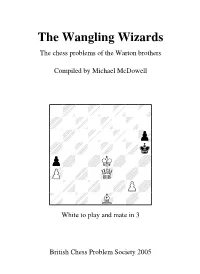

The Wangling Wizards the Chess Problems of the Warton Brothers

The Wangling Wizards The chess problems of the Warton brothers Compiled by Michael McDowell ½ û White to play and mate in 3 British Chess Problem Society 2005 The Wangling Wizards Introduction Tom and Joe Warton were two of the most popular British chess problem composers of the twentieth century. They were often compared to the American "Puzzle King" Sam Loyd because they rarely composed problems illustrating formal themes, instead directing their energies towards hoodwinking the solver. Piquant keys and well-concealed manoeuvres formed the basis of a style that became known as "Wartonesque" and earned the brothers the nickname "the Wangling Wizards". Thomas Joseph Warton was born on 18 th July 1885 at South Mimms, Hertfordshire, and Joseph John Warton on 22 nd September 1900 at Notting Hill, London. Another brother, Edwin, also composed problems, and there may have been a fourth composing Warton, as a two-mover appeared in the August 1916 issue of the Chess Amateur under the name G. F. Warton. After a brief flourish Edwin abandoned composition, although as late as 1946 he published a problem in Chess . Tom and Joe began composing around 1913. After Tom’s early retirement from the Metropolitan Police Force they churned out problems by the hundred, both individually and as a duo, their total output having been estimated at over 2600 problems. Tom died on 23rd May 1955. Joe continued to compose, and in the 1960s published a number of joints with Jim Cresswell, problem editor of the Busmen's Chess Review , who shared his liking for mutates. Many pleasing works appeared in the BCR under their amusing pseudonym "Wartocress". -

White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents

Chess E-Magazine Interactive E-Magazine Volume 3 • Issue 1 January/February 2012 Chess Gambits Chess Gambits The Immortal Game Canada and Chess Anderssen- Vs. -Kieseritzky Bill Wall’s Top 10 Chess software programs C Seraphim Press White Knight Review Chess E-Magazine January/February - 2012 Table of Contents Editorial~ “My Move” 4 contents Feature~ Chess and Canada 5 Article~ Bill Wall’s Top 10 Software Programs 9 INTERACTIVE CONTENT ________________ Feature~ The Incomparable Kasparov 10 • Click on title in Table of Contents Article~ Chess Variants 17 to move directly to Unorthodox Chess Variations page. • Click on “White Feature~ Proof Games 21 Knight Review” on the top of each page to return to ARTICLE~ The Immortal Game 22 Table of Contents. Anderssen Vrs. Kieseritzky • Click on red type to continue to next page ARTICLE~ News Around the World 24 • Click on ads to go to their websites BOOK REVIEW~ Kasparov on Kasparov Pt. 1 25 • Click on email to Pt.One, 1973-1985 open up email program Feature~ Chess Gambits 26 • Click up URLs to go to websites. ANNOTATED GAME~ Bareev Vs. Kasparov 30 COMMENTARY~ “Ask Bill” 31 White Knight Review January/February 2012 White Knight Review January/February 2012 Feature My Move Editorial - Jerry Wall [email protected] Well it has been over a year now since we started this publication. It is not easy putting together a 32 page magazine on chess White Knight every couple of months but it certainly has been rewarding (maybe not so Review much financially but then that really never was Chess E-Magazine the goal). -

“CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION Issue 1

“CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION Issue 1 “CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION 2013, Botswana Chess Review In this Issue; BY: KEENESE NEOYAME KATISENGE 1. Historic World Chess Federation’s Visit to Botswana 2. Field Performance 3. Administration & Developmental Programs BCF PUBLIC RELATIONS DIRECTOR 4. Social Responsibility, Marketing and Publicity / Sponsorships B “Checkmate” is the first edition of BCF e-Newsletter. It will be released on a quarterly basis with a review of chess events for the past period. In Chess circles, “Checkmate” announces the end of the game the same way this newsletter reviews performance at the end of a specified period. The aim of “Checkmate” is to maintain contact with all stakeholders, share information with interesting chess highlights as well as increase awareness in a BNSC Chair Solly Reikeletseng,Mr Mogotsi from Debswana, cost-effective manner. Mr Bobby Gaseitsewe from BNSC and BCF Exo during The 2013 Re-ba bona-ha Youth Championships 2013, Botswana Chess Review Under the leadership of the new president, Tshenolo Maruatona,, Botswana Chess continues to steadily Minister of Youth, Sports & Culture Hon. Shaw Kgathi and cement its place as one of the fastest growing the FIDE Delegation during their visit to Botswana in 2013 sporting codes in the country. BCF has held a number of activities aimed at developing and growing the sport in the country. “CHECKMATE” FIRST EDITION | Issue 1 2 2013 Review Cont.. The president of the federation, Mr Maruatona attended two key International Congresses, i.e Zonal Meeting held during The -

Graphical Summary of E4 Openings (Pdf)

Summary 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Openings 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Sc6 3. Lb5 Spanish Game (Ruy Lopez) 3. c3 Sf6 Ponziani Opening 2 3. Nc3 Sf6 Four Knights Opening 3. Lc4 Italien Game 3. d4 Göring Gambit 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 d6 Philidor Defence 2. f5 Latvian Gambit 2. f6? Damiano Defence 2. Sf6 Petroff Defence 2 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Sc6 3. Lc4 Italian Game Vc5 Giuoco Piano Ve7 Hungarian Defence Sf6 Two Knights Defence O.Wolkenhauer 16 January 2005 Scandinavian Defence (Center Counter) 1. e4 d5 2. exd5 Sf6 sharper play than Wxd5 3. d4 Sxd5 4. c4 Sb6 see below for …Sb4 3 2 4. Nf3 solid for black 3 4 3 1. e4 d5 2. exd5 Wxd5 risky early development 3. Nc3 Wa5 4. d4 f6 4 S 5. Nf3 Vf5 2 3 5 4 3 5 1. e4 d5 2. exd5 Sf6 3. d4 Sxd5 4. c4 Sb4 2 5. Qa4+? Sc6! Trap: white wins a piece but…6 5 6. d5 b5 3 7. Qxb5 Sc2+ 8. Kd1 Vd7! 9. a6 b4 3 Q S 5 4 4 10. Qb7 Vc6 0-1 O.Wolkenhauer 16 January 2005 Damiano Defence 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 f6? 4 5 3. Nxe5! …fxe5 a sound sacrifice for white. 3. …We7 as good for white 7 4. Nf3 Wxe4+ 6 3 5 5. Le2 7 3 4 4. Qh5+ Me7 6 4. ... g6 5. Qxe5+ wins the rook. 5. Qxe5+ Mf7 6. Lc4+ d5 7. Lxd5+ Mg6 8. h4! h5 8. …h6 9 9. -

Chess Openings

Chess Openings PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 10 Jun 2014 09:50:30 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Chess opening 1 e4 Openings 25 King's Pawn Game 25 Open Game 29 Semi-Open Game 32 e4 Openings – King's Knight Openings 36 King's Knight Opening 36 Ruy Lopez 38 Ruy Lopez, Exchange Variation 57 Italian Game 60 Hungarian Defense 63 Two Knights Defense 65 Fried Liver Attack 71 Giuoco Piano 73 Evans Gambit 78 Italian Gambit 82 Irish Gambit 83 Jerome Gambit 85 Blackburne Shilling Gambit 88 Scotch Game 90 Ponziani Opening 96 Inverted Hungarian Opening 102 Konstantinopolsky Opening 104 Three Knights Opening 105 Four Knights Game 107 Halloween Gambit 111 Philidor Defence 115 Elephant Gambit 119 Damiano Defence 122 Greco Defence 125 Gunderam Defense 127 Latvian Gambit 129 Rousseau Gambit 133 Petrov's Defence 136 e4 Openings – Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence 140 Sicilian Defence, Alapin Variation 159 Sicilian Defence, Dragon Variation 163 Sicilian Defence, Accelerated Dragon 169 Sicilian, Dragon, Yugoslav attack, 9.Bc4 172 Sicilian Defence, Najdorf Variation 175 Sicilian Defence, Scheveningen Variation 181 Chekhover Sicilian 185 Wing Gambit 187 Smith-Morra Gambit 189 e4 Openings – Other variations 192 Bishop's Opening 192 Portuguese Opening 198 King's Gambit 200 Fischer Defense 206 Falkbeer Countergambit 208 Rice Gambit 210 Center Game 212 Danish Gambit 214 Lopez Opening 218 Napoleon Opening 219 Parham Attack 221 Vienna Game 224 Frankenstein-Dracula Variation 228 Alapin's Opening 231 French Defence 232 Caro-Kann Defence 245 Pirc Defence 256 Pirc Defence, Austrian Attack 261 Balogh Defense 263 Scandinavian Defense 265 Nimzowitsch Defence 269 Alekhine's Defence 271 Modern Defense 279 Monkey's Bum 282 Owen's Defence 285 St. -

Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames

Games of No Chance MSRI Publications Volume 29, 1996 Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames LEWIS STILLER Abstract. This article has three chief aims: (1) To show the wide utility of multilinear algebraic formalism for high-performance computing. (2) To describe an application of this formalism in the analysis of chess endgames, and results obtained thereby that would have been impossible to compute using earlier techniques, including a win requiring a record 243 moves. (3) To contribute to the study of the history of chess endgames, by focusing on the work of Friedrich Amelung (in particular his apparently lost analysis of certain six-piece endgames) and that of Theodor Molien, one of the founders of modern group representation theory and the first person to have systematically numerically analyzed a pawnless endgame. 1. Introduction Parallel and vector architectures can achieve high peak bandwidth, but it can be difficult for the programmer to design algorithms that exploit this bandwidth efficiently. Application performance can depend heavily on unique architecture features that complicate the design of portable code [Szymanski et al. 1994; Stone 1993]. The work reported here is part of a project to explore the extent to which the techniques of multilinear algebra can be used to simplify the design of high- performance parallel and vector algorithms [Johnson et al. 1991]. The approach is this: Define a set of fixed, structured matrices that encode architectural primitives • of the machine, in the sense that left-multiplication of a vector by this matrix is efficient on the target architecture. Formulate the application problem as a matrix multiplication. -

Positional Attacks

Positional Attacks Joel Johnson Edited by: Patrick Hammond © Joel Johnson, January 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from Joel Johnson. Edited by: Patrick Hammond Cover Photography: Barry M. Evans Cover Design and Proofreading: Joel Johnson Game Searching: Joel Johnson, Richard J. Cowan, William Parker, Nick Desmarais Game Contributors: Brian Wall, Jack Young, Clyde Nakamura, James Rizzitano, Keith Hayward, Hal Terrie, Richard Cowan, Jesús Seoane, William Parker, Domingos Perego, Danielle Rice Linares Diagram and Linares Figurine fonts ©1993-2003 by Alpine Electronics, Steve Smith Alpine Electronics 703 Ivinson Ave. Laramie, WY 82070 Email: Alpine Chess Fonts ([email protected]) Website: http://www.partae.com/fonts/ Pressure Gauge graphic Image Copyright Araminta, 2012 Used under license from Shutterstock.com In Memoriam to my step dad and World War II Navy, Purple Heart Recipient, Theodore Kosiavelon, 12/22/1921 – 11/09/2012 CONTENTS Preface 7 Kudos 7 Brian Wall 8 Young Rising Stars 27 Daniil Dubov 27 Wei Yi 30 Section A – Pawn Roles 36 Pawn Structure 37 Ugliest Pawn Structure Ever? 38 Anchoring 41 Alien Pawn 48 Pawn Lever 63 Pawn Break 72 Center Pawn Mass 75 Isolated Pawn 94 Black Strategy 95 White Strategy 96 Eliminate the Isolated Pawn Weakness with d4-d5 96 Sacrifices on e6 & f7 , Often with f2-f4-f5 Played 99 Rook Lift Attack 104 Queenside Play 111 This Is Not Just -

CHESS MASTERPIECES: (Later, in Europe, Replaced by a HIGHLIGHTS from the DR

CHESS MASTERPIECES: (later, in Europe, replaced by a HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE DR. queen). These were typically flanKed GEORGE AND VIVIAN DEAN by elephants (later to become COLLECTION bishops), though in this case, they are EXHIBITION CHECKLIST camels with drummers; cavalrymen (later to become Knights); and World Chess Hall of Fame chariots or elephants, (later to Saint Louis, Missouri 2.1. Abstract Bead anD Dart Style Set become rooKs or “castles”). A September 9, 2011-February 12, with BoarD, India, 1700s. Natural and frontline of eight foot soldiers 2012 green-stained ivory, blacK lacquer- (pawns) completed each side. work folding board with silver and mother-of-pearl. This classical Indian style is influenced by the Islamic trend toward total abstraction of the design. The pieces are all lathe- turned. The blacK lacquer finish, made in India from the husKs of the 1.1. Neresheimer French vs. lac insect, was first developed by the Germans Set anD Castle BoarD, Chinese. The intricate inlaid silver Hanau, Germany, 1905-10. Silver and grid pattern traces alternating gilded silver, ivory, diamonds, squares filled with lacy inscribed fern sapphires, pearls, amethysts, rubies, leaf designs and inlaid mother-of- and marble. pearl disKs. These decorations 2.3. Mogul Style Set with combine a grid of squares, common Presentation Case, India, 1800s. Before WWI, Neresheimer, of Hanau, to Western forms of chess, with Beryl with inset diamonds, rubies, Germany, was a leading producer of another grid of inlaid center points, and gold, wooden presentation case ornate silverware and decorative found in Japanese and Chinese clad in maroon velvet and silk-lined. -

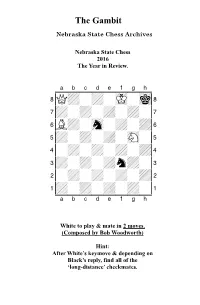

2016 Year in Review

The Gambit Nebraska State Chess Archives Nebraska State Chess 2016 The Year in Review. XABCDEFGHY 8Q+-+-mK-mk( 7+-+-+-+-' 6L+-sn-+-+& 5+-+-+-sN-% 4-+-+-+-+$ 3+-+-+n+-# 2-+-+-+-+" 1+-+-+-+-! xabcdefghy White to play & mate in 2 moves. (Composed by Bob Woodworth) Hint: After White’s keymove & depending on Black’s reply, find all of the ‘long-distance’ checkmates. Gambit Editor- Kent Nelson The Gambit serves as the official publication of the Nebraska State Chess Association and is published by the Lincoln Chess Foundation. Send all games, articles, and editorial materials to: Kent Nelson 4014 “N” St Lincoln, NE 68510 [email protected] NSCA Officers President John Hartmann Treasurer Lucy Ruf Historical Archivist Bob Woodworth Secretary Gnanasekar Arputhaswamy Webmaster Kent Smotherman Regional VPs NSCA Committee Members Vice President-Lincoln- John Linscott Vice President-Omaha- Michael Gooch Vice President (Western) Letter from NSCA President John Hartmann January 2017 Hello friends! Our beloved game finds itself at something of a crossroads here in Nebraska. On the one hand, there is much to look forward to. We have a full calendar of scholastic events coming up this spring and a slew of promising juniors to steal our rating points. We have more and better adult players playing rated chess. If you’re reading this, we probably (finally) have a functional website. And after a precarious few weeks, the Spence Chess Club here in Omaha seems to have found a new home. And yet, there is also cause for concern. It’s not clear that we will be able to have tournaments at UNO in the future.