Keeping Sonic Hedgehog Under the Thumb, Genetic Regulation of Limb Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Next Generation Sequencing Panels for Disorders of Sex Development

Next Generation Sequencing Panels for Disorders of Sex Development Disorders of Sex Development – Overview Disorders of sex development (DSDs) occur when sex development does not follow the course of typical male or female patterning. Types of DSDs include congenital development of ambiguous genitalia, disjunction between the internal and external sex anatomy, incomplete development of the sex anatomy, and abnormalities of the development of gonads (such as ovotestes or streak ovaries) (1). Sex chromosome anomalies including Turner syndrome and Klinefelter syndrome as well as sex chromosome mosaicism are also considered to be DSDs. DSDs can be caused by a wide range of genetic abnormalities (2). Determining the etiology of a patient’s DSD can assist in deciding gender assignment, provide recurrence risk information for future pregnancies, and can identify potential health problems such as adrenal crisis or gonadoblastoma (1, 3). Sex chromosome aneuploidy and copy number variation are common genetic causes of DSDs. For this reason, chromosome analysis and/or microarray analysis typically should be the first genetic analysis in the case of a patient with ambiguous genitalia or other suspected disorder of sex development. Identifying whether a patient has a 46,XY or 46,XX karyotype can also be helpful in determining appropriate additional genetic testing. Abnormal/Ambiguous Genitalia Panel Our Abnormal/Ambiguous Genitalia Panel includes mutation analysis of 72 genes associated with both syndromic and non-syndromic DSDs. This comprehensive panel evaluates a broad range of genetic causes of ambiguous or abnormal genitalia, including conditions in which abnormal genitalia are the primary physical finding as well as syndromic conditions that involve abnormal genitalia in addition to other congenital anomalies. -

The Genetic Basis for Skeletal Diseases

insight review articles The genetic basis for skeletal diseases Elazar Zelzer & Bjorn R. Olsen Harvard Medical School, Department of Cell Biology, 240 Longwood Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA (e-mail: [email protected]) We walk, run, work and play, paying little attention to our bones, their joints and their muscle connections, because the system works. Evolution has refined robust genetic mechanisms for skeletal development and growth that are able to direct the formation of a complex, yet wonderfully adaptable organ system. How is it done? Recent studies of rare genetic diseases have identified many of the critical transcription factors and signalling pathways specifying the normal development of bones, confirming the wisdom of William Harvey when he said: “nature is nowhere accustomed more openly to display her secret mysteries than in cases where she shows traces of her workings apart from the beaten path”. enetic studies of diseases that affect skeletal differentiation to cartilage cells (chondrocytes) or bone cells development and growth are providing (osteoblasts) within the condensations. Subsequent growth invaluable insights into the roles not only of during the organogenesis phase generates cartilage models individual genes, but also of entire (anlagen) of future bones (as in limb bones) or membranous developmental pathways. Different mutations bones (as in the cranial vault) (Fig. 1). The cartilage anlagen Gin the same gene may result in a range of abnormalities, are replaced by bone and marrow in a process called endo- and disease ‘families’ are frequently caused by mutations in chondral ossification. Finally, a process of growth and components of the same pathway. -

Mutations Within Or Upstream of the Basic Helixð Loopð Helix Domain of the TWIST Gene Are Specific to Saethre-Chotzen Syndrome

European Journal of Human Genetics (1999) 7, 27–33 © 1999 Stockton Press All rights reserved 1018–4813/99 $12.00 t http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/ejhg ARTICLES Mutations within or upstream of the basic helix–loop–helix domain of the TWIST gene are specific to Saethre-Chotzen syndrome Vincent El Ghouzzi, Elisabeth Lajeunie, Martine Le Merrer, Val´erie Cormier-Daire, Dominique Renier, Arnold Munnich and Jacky Bonaventure Unit´e de Recherches sur les Handicaps G´en´etiques de l’Enfant, Institut Necker, Paris, France Saethre-Chotzen syndrome (ACS III) is an autosomal dominant craniosynostosis syndrome recently ascribed to mutations in the TWIST gene, a basic helix–loop–helix (b-HLH) transcription factor regulating head mesenchyme cell development during cranial neural tube formation in mouse. Studying a series of 22 unrelated ACS III patients, we have found TWIST mutations in 16/22 cases. Interestingly, these mutations consistently involved the b-HLH domain of the protein. Indeed, mutant genotypes included frameshift deletions/insertions, nonsense and missense mutations, either truncating or disrupting the b-HLH motif of the protein. This observation gives additional support to the view that most ACS III cases result from loss-of-function mutations at the TWIST locus. The P250R recurrent FGFR 3 mutation was found in 2/22 cases presenting mild clinical manifestations of the disease but 4/22 cases failed to harbour TWIST or FGFR 3 mutations. Clinical re-examination of patients carrying TWIST mutations failed to reveal correlations between the mutant genotype and severity of the phenotype. Finally, since no TWIST mutations were detected in 40 cases of isolated coronal craniosynostosis, the present study suggests that TWIST mutations are specific to Saethre- Chotzen syndrome. -

Genetics of Congenital Hand Anomalies

G. C. Schwabe1 S. Mundlos2 Genetics of Congenital Hand Anomalies Die Genetik angeborener Handfehlbildungen Original Article Abstract Zusammenfassung Congenital limb malformations exhibit a wide spectrum of phe- Angeborene Handfehlbildungen sind durch ein breites Spektrum notypic manifestations and may occur as an isolated malforma- an phänotypischen Manifestationen gekennzeichnet. Sie treten tion and as part of a syndrome. They are individually rare, but als isolierte Malformation oder als Teil verschiedener Syndrome due to their overall frequency and severity they are of clinical auf. Die einzelnen Formen kongenitaler Handfehlbildungen sind relevance. In recent years, increasing knowledge of the molecu- selten, besitzen aber aufgrund ihrer Häufigkeit insgesamt und lar basis of embryonic development has significantly enhanced der hohen Belastung für Betroffene erhebliche klinische Rele- our understanding of congenital limb malformations. In addi- vanz. Die fortschreitende Erkenntnis über die molekularen Me- tion, genetic studies have revealed the molecular basis of an in- chanismen der Embryonalentwicklung haben in den letzten Jah- creasing number of conditions with primary or secondary limb ren wesentlich dazu beigetragen, die genetischen Ursachen kon- involvement. The molecular findings have led to a regrouping of genitaler Malformationen besser zu verstehen. Der hohe Grad an malformations in genetic terms. However, the establishment of phänotypischer Variabilität kongenitaler Handfehlbildungen er- precise genotype-phenotype correlations for limb malforma- schwert jedoch eine Etablierung präziser Genotyp-Phänotyp- tions is difficult due to the high degree of phenotypic variability. Korrelationen. In diesem Übersichtsartikel präsentieren wir das We present an overview of congenital limb malformations based Spektrum kongenitaler Malformationen, basierend auf einer ent- 85 on an anatomic and genetic concept reflecting recent molecular wicklungsbiologischen, anatomischen und genetischen Klassifi- and developmental insights. -

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases Biomed Central

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases BioMed Central Review Open Access Brachydactyly Samia A Temtamy* and Mona S Aglan Address: Department of Clinical Genetics, Human Genetics and Genome Research Division, National Research Centre (NRC), El-Buhouth St., Dokki, 12311, Cairo, Egypt Email: Samia A Temtamy* - [email protected]; Mona S Aglan - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 13 June 2008 Received: 4 April 2008 Accepted: 13 June 2008 Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2008, 3:15 doi:10.1186/1750-1172-3-15 This article is available from: http://www.ojrd.com/content/3/1/15 © 2008 Temtamy and Aglan; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Brachydactyly ("short digits") is a general term that refers to disproportionately short fingers and toes, and forms part of the group of limb malformations characterized by bone dysostosis. The various types of isolated brachydactyly are rare, except for types A3 and D. Brachydactyly can occur either as an isolated malformation or as a part of a complex malformation syndrome. To date, many different forms of brachydactyly have been identified. Some forms also result in short stature. In isolated brachydactyly, subtle changes elsewhere may be present. Brachydactyly may also be accompanied by other hand malformations, such as syndactyly, polydactyly, reduction defects, or symphalangism. For the majority of isolated brachydactylies and some syndromic forms of brachydactyly, the causative gene defect has been identified. -

Modeling Congenital Disease and Inborn Errors of Development in Drosophila Melanogaster Matthew J

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Disease Models & Mechanisms (2016) 9, 253-269 doi:10.1242/dmm.023564 REVIEW SUBJECT COLLECTION: TRANSLATIONAL IMPACT OF DROSOPHILA Modeling congenital disease and inborn errors of development in Drosophila melanogaster Matthew J. Moulton and Anthea Letsou* ABSTRACT particularly difficult to manage clinically {e.g. CHARGE syndrome Fly models that faithfully recapitulate various aspects of human manifesting coloboma [emboldened words and phrases are defined disease and human health-related biology are being used for in the glossary (see Box 1)], heart defects, choanal atresia, growth research into disease diagnosis and prevention. Established and retardation, genitourinary malformation and ear abnormalities new genetic strategies in Drosophila have yielded numerous (Hsu et al., 2014), and velocardiofacial or Shprinstzens syndrome substantial successes in modeling congenital disorders or inborn manifesting cardiac anomaly, velopharyngeal insufficiency, errors of human development, as well as neurodegenerative disease aberrant calcium metabolism and immune dysfunction (Chinnadurai and cancer. Moreover, although our ability to generate sequence and Goudy, 2012)}. Estimates suggest that the cause of at least 50% of datasets continues to outpace our ability to analyze these datasets, congenital abnormalities remains unknown (Lobo and Zhaurova, the development of high-throughput analysis platforms in Drosophila 2008). It is vital that we understand the etiology of congenital has provided access through the bottleneck in the identification of anomalies because this knowledge provides a foundation for improved disease gene candidates. In this Review, we describe both the diagnostics as well as the design of preventatives and therapeutics that traditional and newer methods that are facilitating the incorporation of can effectively alleviate or abolish the effects of disease. -

MECHANISMS in ENDOCRINOLOGY: Novel Genetic Causes of Short Stature

J M Wit and others Genetics of short stature 174:4 R145–R173 Review MECHANISMS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY Novel genetic causes of short stature 1 1 2 2 Jan M Wit , Wilma Oostdijk , Monique Losekoot , Hermine A van Duyvenvoorde , Correspondence Claudia A L Ruivenkamp2 and Sarina G Kant2 should be addressed to J M Wit Departments of 1Paediatrics and 2Clinical Genetics, Leiden University Medical Center, PO Box 9600, 2300 RC Leiden, Email The Netherlands [email protected] Abstract The fast technological development, particularly single nucleotide polymorphism array, array-comparative genomic hybridization, and whole exome sequencing, has led to the discovery of many novel genetic causes of growth failure. In this review we discuss a selection of these, according to a diagnostic classification centred on the epiphyseal growth plate. We successively discuss disorders in hormone signalling, paracrine factors, matrix molecules, intracellular pathways, and fundamental cellular processes, followed by chromosomal aberrations including copy number variants (CNVs) and imprinting disorders associated with short stature. Many novel causes of GH deficiency (GHD) as part of combined pituitary hormone deficiency have been uncovered. The most frequent genetic causes of isolated GHD are GH1 and GHRHR defects, but several novel causes have recently been found, such as GHSR, RNPC3, and IFT172 mutations. Besides well-defined causes of GH insensitivity (GHR, STAT5B, IGFALS, IGF1 defects), disorders of NFkB signalling, STAT3 and IGF2 have recently been discovered. Heterozygous IGF1R defects are a relatively frequent cause of prenatal and postnatal growth retardation. TRHA mutations cause a syndromic form of short stature with elevated T3/T4 ratio. Disorders of signalling of various paracrine factors (FGFs, BMPs, WNTs, PTHrP/IHH, and CNP/NPR2) or genetic defects affecting cartilage extracellular matrix usually cause disproportionate short stature. -

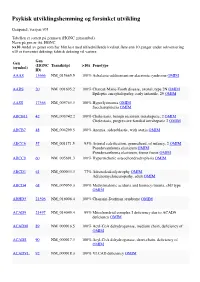

Psykisk Utviklingshemming Og Forsinket Utvikling

Psykisk utviklingshemming og forsinket utvikling Genpanel, versjon v03 Tabellen er sortert på gennavn (HGNC gensymbol) Navn på gen er iht. HGNC >x10 Andel av genet som har blitt lest med tilfredstillende kvalitet flere enn 10 ganger under sekvensering x10 er forventet dekning; faktisk dekning vil variere. Gen Gen (HGNC Transkript >10x Fenotype (symbol) ID) AAAS 13666 NM_015665.5 100% Achalasia-addisonianism-alacrimia syndrome OMIM AARS 20 NM_001605.2 100% Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, axonal, type 2N OMIM Epileptic encephalopathy, early infantile, 29 OMIM AASS 17366 NM_005763.3 100% Hyperlysinemia OMIM Saccharopinuria OMIM ABCB11 42 NM_003742.2 100% Cholestasis, benign recurrent intrahepatic, 2 OMIM Cholestasis, progressive familial intrahepatic 2 OMIM ABCB7 48 NM_004299.5 100% Anemia, sideroblastic, with ataxia OMIM ABCC6 57 NM_001171.5 93% Arterial calcification, generalized, of infancy, 2 OMIM Pseudoxanthoma elasticum OMIM Pseudoxanthoma elasticum, forme fruste OMIM ABCC9 60 NM_005691.3 100% Hypertrichotic osteochondrodysplasia OMIM ABCD1 61 NM_000033.3 77% Adrenoleukodystrophy OMIM Adrenomyeloneuropathy, adult OMIM ABCD4 68 NM_005050.3 100% Methylmalonic aciduria and homocystinuria, cblJ type OMIM ABHD5 21396 NM_016006.4 100% Chanarin-Dorfman syndrome OMIM ACAD9 21497 NM_014049.4 99% Mitochondrial complex I deficiency due to ACAD9 deficiency OMIM ACADM 89 NM_000016.5 100% Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, medium chain, deficiency of OMIM ACADS 90 NM_000017.3 100% Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, short-chain, deficiency of OMIM ACADVL 92 NM_000018.3 100% VLCAD -

Table of Contents

Table of contents Acknowledgements I List of Figures III List of Tables XI List of Abbreviations XIV Summary XVI Part 1 Primary microcephaly 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Primary microcephaly (MCPH) 2 1.2 Structure of cerebral cortex 5 1.3 Development of cerebral cortex 7 1.4 Clinical features of primary microcephaly 8 1.5 MCPH genes and their function 10 1.5.1 Microcephalin (MCPH1) 10 1.5.2 Abnormal spindle like microcephaly associated (ASPM) 11 1.5.3 Cyclin dependent kinase5 regulatory associated protein (CDK5RAP2) 12 1.5.4 Centrosomal protein J (CENPJ) 13 1.5.5 STIL (SCL/TAL1 interrupting locus) 13 1.6 Objectives of study 16 2 MATERIALS AND METHODS 17 2.1 Families studied 17 2.1.1 MCP3 18 2.1. 2 MCP6 19 2.1.3 MCP7 20 2.1.4 MCP9 21 2.1.5 MCP11 22 2.1.6 MCP15 23 2.1. 7 MCP17 24 2.1.8 MCP18 25 2.1.9 MCP21 26 2.1.10 MCP22 27 2.1.11 MCP35 28 2.1.12 MCP36 29 2.2 Clinical data 29 2.3 Blood sampling 32 2.4 DNA extraction 33 2.5 Polymerase chain reaction 33 2.6 Agarose gel electrophoresis 33 2.7 Genotyping using fluorescently labeled primers 34 2.8 Preparation of samples for ABI 3130xl genetic analyzer 35 2.9 Linkage analysis 35 2.10 Mutation screening 36 2.10.1 DNA sequencing 36 2.10.2 Purification of PCR product from agarose gel 37 2.10.3 Purification of PCR product 37 2.10.4 Sequencing PCR reactions 37 2.10.5 Precipitation of sequencing PCR products 38 2.10.6 Sequencing data analysis 38 2.11 Restriction analysis 39 3 RESULTS 51 3.1 Linkage studies 51 3.2 Mutation analysis 52 3.2.1 Sequencing of ASPM in MCPH5 linked families 52 3.2.2 Compound heterozygous -

Blueprint Genetics Comprehensive Growth Disorders / Skeletal

Comprehensive Growth Disorders / Skeletal Dysplasias and Disorders Panel Test code: MA4301 Is a 374 gene panel that includes assessment of non-coding variants. This panel covers the majority of the genes listed in the Nosology 2015 (PMID: 26394607) and all genes in our Malformation category that cause growth retardation, short stature or skeletal dysplasia and is therefore a powerful diagnostic tool. It is ideal for patients suspected to have a syndromic or an isolated growth disorder or a skeletal dysplasia. About Comprehensive Growth Disorders / Skeletal Dysplasias and Disorders This panel covers a broad spectrum of diseases associated with growth retardation, short stature or skeletal dysplasia. Many of these conditions have overlapping features which can make clinical diagnosis a challenge. Genetic diagnostics is therefore the most efficient way to subtype the diseases and enable individualized treatment and management decisions. Moreover, detection of causative mutations establishes the mode of inheritance in the family which is essential for informed genetic counseling. For additional information regarding the conditions tested on this panel, please refer to the National Organization for Rare Disorders and / or GeneReviews. Availability 4 weeks Gene Set Description Genes in the Comprehensive Growth Disorders / Skeletal Dysplasias and Disorders Panel and their clinical significance Gene Associated phenotypes Inheritance ClinVar HGMD ACAN# Spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia, aggrecan type, AD/AR 20 56 Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, Kimberley -

Blueprint Genetics Comprehensive Skeletal Dysplasias and Disorders

Comprehensive Skeletal Dysplasias and Disorders Panel Test code: MA3301 Is a 251 gene panel that includes assessment of non-coding variants. Is ideal for patients with a clinical suspicion of disorders involving the skeletal system. About Comprehensive Skeletal Dysplasias and Disorders This panel covers a broad spectrum of skeletal disorders including common and rare skeletal dysplasias (eg. achondroplasia, COL2A1 related dysplasias, diastrophic dysplasia, various types of spondylo-metaphyseal dysplasias), various ciliopathies with skeletal involvement (eg. short rib-polydactylies, asphyxiating thoracic dysplasia dysplasias and Ellis-van Creveld syndrome), various subtypes of osteogenesis imperfecta, campomelic dysplasia, slender bone dysplasias, dysplasias with multiple joint dislocations, chondrodysplasia punctata group of disorders, neonatal osteosclerotic dysplasias, osteopetrosis and related disorders, abnormal mineralization group of disorders (eg hypopohosphatasia), osteolysis group of disorders, disorders with disorganized development of skeletal components, overgrowth syndromes with skeletal involvement, craniosynostosis syndromes, dysostoses with predominant craniofacial involvement, dysostoses with predominant vertebral involvement, patellar dysostoses, brachydactylies, some disorders with limb hypoplasia-reduction defects, ectrodactyly with and without other manifestations, polydactyly-syndactyly-triphalangism group of disorders, and disorders with defects in joint formation and synostoses. Availability 4 weeks Gene Set Description -

Daniel Lopo Polla.Pdf

Pró-Reitoria de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa Programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto Sensu em Ciências Genômicas e Biotecnologia SEQUENCIAMENTO DE EXOMA PARCIAL COMO FERRAMENTA DE DIAGNÓSTICO MOLECULAR DE DISPLASIAS ESQUELÉTICAS Autor: Daniel Lôpo Polla Orientador: Dr. Robert Pogue Coorientador: Dr. Rinaldo Wellerson Pereira Brasília - DF 2014 DANIEL LÔPO POLLA SEQUENCIAMENTO DE EXOMA PARCIAL COMO FERRAMENTA DE DIAGNÓSTICO MOLECULAR DE DISPLASIAS ESQUELÉTICAS Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação Stricto Sensu em Ciências Genômicas e Biotecnologia da Universidade Católica de Brasília, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do Título de Mestre em Ciências Genômicas e Biotecnologia. Orientador: Dr. Robert Pogue Coorientador: Dr. Rinaldo Wellerson Pereira Brasília 2014 P771s Polla, Daniel Lôpo. Sequenciamento de exoma parcial como ferramenta de diagnóstico molecular de displasias esqueléticas. / Daniel Lôpo Polla – 2014. 133 f.; il : 30 cm Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Católica de Brasília, 2014. Orientação: Prof. Dr. Robert Pogue Coorientação: Prof. Dr. Rinaldo Wellerson Pereira 1. Biotecnologia. 2. Diagnóstico molecular. 3. Displasia esquelética. I. Pogue, Robert, orient. II. Pereira, Rinaldo Wllerson, coorient. III. Título. CDU 577.21 Ficha elaborada pela Biblioteca Pós-Graduação da UCB Dissertação de autoria de Daniel Lôpo Polla, intitulada “SEQUENCIAMENTO DE EXOMA PARCIAL COMO FERRAMENTA DE DIAGNÓSTICO MOLECULAR DE DISPLASIAS ESQUELÉTICAS”, apresentada como requisito parcial para a obtenção de grau de Mestre em Ciências Genômicas e Biotecnologia da Universidade Católica de Brasília, em 12 de março de 2014, defendida e aprovada pela banca examinadora abaixo assinada: Brasília 2014 AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço em primeiro lugar a Deus que iluminou o meu caminho durante mais esta caminhada, dando-me força e paciência para superar os desafios.