Mary Popp INTERVIEWER: DATE: PLACE: Esthe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folklore Revival.Indb

Folklore Revival Movements in Europe post 1950 Shifting Contexts and Perspectives Edited by Daniela Stavělová and Theresa Jill Buckland 1 2 Folklore Revival Movements in Europe post 1950 Shifting Contexts and Perspectives Edited by Daniela Stavělová and Theresa Jill Buckland Institute of Ethnology of the Czech Academy of Sciences Prague 2018 3 Published as a part of the project „Tíha a beztíže folkloru. Folklorní hnutí druhé poloviny 20. století v českých zemích / Weight and Weightlessness of the Folklore. The Folklore Movement of the Second Half of the 20th Century in Czech Lands,“ supported by Czech Science Foundation GA17-26672S. Edited volume based on the results of the International Symposium Folklore revival movement of the second half of the 20th century in shifting cultural, social and political contexts organ- ized by the Institute of Ethnology in cooperation with the Academy of Performing Arts, Prague, October 18.-19., 2017. Peer review: Prof. PaedDr. Bernard Garaj, CSc. Prof. Andriy Nahachewsky, PhD. Editorial Board: PhDr. Barbora Gergelová PhDr. Jana Pospíšilová, Ph.D. PhDr. Jarmila Procházková, Ph.D. Doc. Mgr. Daniela Stavělová, CSc. PhDr. Jiří Woitsch, Ph.D. (Chair) Translations: David Mraček, Ph.D. Proofreading: Zita Skořepová, Ph.D. © Institute of Ethnology of the Czech Academy of Sciences, 2018 ISBN 978-80-88081-22-7 (Etnologický ústav AV ČR, v. v. i., Praha) 4 Table of contents: Preface . 7 Part 1 Politicizing Folklore On the Legal and Political Framework of the Folk Dance Revival Movement in Hungary in the Second Half of the Twentieth Century Lázsló Felföldi . 21 The Power of Tradition(?): Folk Revival Groups as Bearers of Folk Culture Martina Pavlicová. -

Dialectical Interactions Between Culture, History, and the Construction of the Czech Vozembouch

{12 Constructing the Sound of Devils: Dialectical Interactions between Culture, History, and the Construction of the Czech Vozembouch William Connor Abstract: The vozembouch is a folk playing styles to inform construction instrument that has evolved through decisions. Alongside this individuality, centuries of dialectical interactions however, some staple elements have with Slavic (and Germanic) cultures. been maintained, which contribute The instrument has developed from to the instrument’s almost ubiquitous a percussive bowed singlestring familiarity among Czech people. One fiddle to being primarily a percussion of the elements is the use of anthro instrument, often constructed without pomorphic/zoomorphic heads to adorn strings, and it has shifted back and the top of the instrument. Often, these forth over time between being a promi heads will evoke characters from folk nently used or allbutextinct instrument tales, most commonly a devil head or in Czech culture. Vozembouchy (pl.) čertí hlava. In this paper, I draw from have evolved from medieval pagan literary sources and my fieldwork with ritual enhancers to minstrel instruments vozembouch makers and players to to percussion reminding some Slavic discuss the ways in which dialectical people of their heritage in troubled engagement of the vozembouch with times, and has been part of a folk music Slavic culture has shaped the evolution revival that has resulted in renewed of its construction, and suggest how interest in traditional performance on a detailed study of the making of this the instrument, as well as new, modern instrument can highlight the devel musical directions embraced by play opment of the vozembouch’s cultural ers spanning many generations. -

STÁHNOUT Digitální Verzi

N Á R O D O P I S N Á 5/25/2019017 JOURNAL OF ETHNOLOGY JOURNAL OF ETHNOLOGY 5/2019 – AUTHORS OF STUDIES: Doc. PhDr. Daniel DRÁPALA, Ph.D., studied ethnology and history at the Faculty of Arts, Masaryk University in Brno, where he works at the Department of European Ethnology. Between 1999 and 2007 he worked at the Wallachian Open-Air Museum in Rožnov pod Radhoštěm. He focusses on traditional forms of nutrition, local and regional identity, customary traditions, and intangible cultural heritage. Contact: [email protected] Mgr. et Mgr. Oto POLOUČEK, Ph.D., graduated in ethnology from the Faculty of Arts, Masaryk University in Brno, and in oral history – contemporary history from the Faculty of Humanities, Charles University. He is presently working as a lecturer at the Department of European Ethnology at the Faculty of Arts, Masaryk University. He focusses mainly on twentieth-century transformations in the countryside and their influence on contemporary problems, the social atmosphere, and the identity of rural residents. Contact: [email protected] Mgr. Michal PAVLÁSEK, Ph.D., works at the Brno branch of the Institute of Ethnology of the Czech Academy of Sciences. He also gives lectures at the Faculty of Arts, Masaryk University in Brno. He is a co-founder of the Anthropictures z.s. research studio. In addition to research on Czech expatriates living in eastern and south-eastern Europe, he also focusses on current migration and refugee issues, memory politics, and social marginalization. He also approaches these phenomena through ethnographic movies and documentaries. Contact: [email protected] PhDr. -

Czech Music in Nebraska

Czech Music in Nebraska Ceska Hudba v Nebrasce OUR COVER PICTURE The Pavlik Band of Verdigre, Nebraska, was organized in 1878 by the five Pavlik brothers: Matej, John, Albert, Charles and Vaclav. Mr. Vaclav Tomek also played in the band. (Photo courtesy of Edward S. Pavlik, Verdigre, Neraska). Editor Vladimir Kucera Co-editor DeLores Kucera Copyright 1980 by Vladimir Kucera DeLores Kucera Published 1980 Bohemians (Czechs) as a whole are extremely fond of dramatic performances. One of their sayings is “The stage is the school of life.” A very large percentage are good musicians, so that wherever even a small group lives, they are sure to have a very good band. Ruzena Rosicka They love their native music, with its pronounced and unusual rhythm especially when played by their somewhat martial bands. A Guide to the Cornhusker State Czechs—A Nation of Musicians An importantCzechoslovakian folklore is music. Song and music at all times used to accompany man from the cradle to the grave and were a necessary accompaniment of all important family events. The most popular of the musical instruments were bagpipes, usually with violin, clarinet and cembalo accompaniment. Typical for pastoral soloist music were different types of fifes and horns, the latter often monstrous contraptions, several feet long. Traditional folk music has been at present superseded by modern forms, but old rural musical instruments and popular tunes have been revived in amateur groups of folklore music or during folklore festivals. ZLATE CESKE VZPOMINKY GOLDEN CZECH MEMORIES There is an old proverb which says that every Czech is born, not with a silver spoon in his mouth, but with a violin under his pillow. -

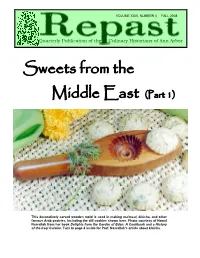

Sweets from the Middle East (Part 1)

VOLUMEVOLUME XVI, XXIV, NUMBER NUMBER 4 4 FALL FALL 2000 2008 Quarterly Publication of the Culinary Historians of Ann Arbor Sweets from the Middle East (Part 1) This decoratively carved wooden mold is used in making ma'moul, kleicha, and other famous Arab pastries, including the dill cookies shown here. Photo courtesy of Nawal Nasrallah from her book Delights from the Garden of Eden: A Cookbook and a History of the Iraqi Cuisine. Turn to page 4 inside for Prof. Nasrallah’s article about kleicha. REPAST VOLUME XXIV, NUMBER 4 FALL 2008 Editor’s Note on Baklava Second Helpings Allowed! Charles Perry, who wrote the article “Damascus Cuisine” in our last issue, was the editor of a book Medieval Arab Cookery (Prospect Books, 2001) that sheds further light on the origins of baklava, the Turkish sweet discussed by Sheilah Kaufman in this issue. A dish described in a 13th-Century Baghdad cookery Sweets from the manuscript appears to be an early version of baklava, consisting of thin sheets of bread rolled around a marzipan-like filling of almond, sugar, and rosewater (pp. 84-5). The name given to this Middle East, Part 2 sweet was lauzinaj, from an Aramaic root for “almond”. Perry argues (p. 210) that this word gave birth to our term lozenge, the diamond shape in which later versions of baklava were often Scheduled for our Winter 2009 issue— sliced, even up to today. Interestingly, in modern Turkish the word baklava itself is used to refer to this geometrical shape. • Joan Peterson, “Halvah in Ottoman Turkey” Further information about the Baklava Procession mentioned • Tim Mackintosh-Smith, “A Note on the by Sheilah can be found in an article by Syed Tanvir Wasti, Evolution of Hindustani Sweetmeats” “The Ottoman Ceremony of the Royal Purse”, Middle Eastern Studies 41:2 (March 2005), pp. -

Texas Co-Op Power • January 2014

LOCAL ELECTRIC COOPERATIVE EDITION JANUARY 2014 Fence-Cutters War The Texas Giants Mushroom Recipes STUFF of LEGENDS The best kolach? Why, it’s at every stop along the trailtrail. SIMPLIFY YOUR COMPLEX COME VISIT US AT THE FORT WORTH STOCK SHOW A PLACE FOR THE HORSES. A PLACE FOR THE HAY.HAAYYY.. A PLACEP FOR... Mueller’s Choice Series buildings are completely customized to meet your needs. Whether you need one building or multiple structures for your farm, ranch or business, our buildings provide functionality to help simplify your life. www.MuellerInc.com 877-2-MUELLER (877-268-3553) January Since 1944 2014 FAVORITES 33 Texas History Towering Texans Tour with Circus By Martha Deeringer 35 Recipes Growing Demand for Mushrooms 39 Focus on Texas Looking Up 40 Around Texas List of Local Events 42 Hit the Road Battleship Texas By Jeff Joiner ONLINE TexasCoopPower.com Texas USA LeTourneau: A Mover and a Shaker FEATURES By K.A. Young Observations The Kolach Trail At Czech bakeries, esteemed pastry is Those Who Can, Teach served with heritage and pride—and apricot and cream By Camille Wheeler cheese By Jeff Siegel • Photos by Rick Patrick 8 Barbed Wire, Barbaric Backlash Fences that stretched across vast frontier pushed tempers past peaceable boundaries during the fence-cutters war By E.R. Bills 14 Around Texas: Youngsters show off poultry, rabbits, lambs and steers at the Blanco County Youth Council Stock Show, January 24–26 in Johnson City. 40 42 14 35 39 COVER PHOTO Ryan Halko is surrounded by kolache at the Village Bakery in West. -

Czech Music Guide

CZECH MUSIC GUIDE CZECH MUSIC GUIDE Supported by Ministry of Culture Czech Republic © 2011 Arts and Theatre Institute Second modified edition First printing ISBN 978-80-7008-269-0 No: 625 All rights reserved CONTENT ABOUT THE CZECH REPUBLIC 12 A SHORT HISTORY OF MUSIC 13 THE MIDDLE AGES (CA 850–1440) 13 THE RENAISSANCE 13 THE BAROQUE 13 CLASSICISM 14 ROMANTICISM/NATIONAL MUSIC 14 THE PERIOD 1890–1945 16 CZECH MUSIC AFTER 1945 19 THE SIXTIES/AVANT-GARDE, NEW MUSIC 22 THE SEVENTIES AND EIGHTIES 25 CONTEMPORARY MUSICAL LIFE 29 CURRENT CULTURE POLICY 37 MUSIC INSTITUTIONS 38 THE MUSIC EDUCATION SYSTEM 50 ARCHIVES, LIBRARIES, SCIENCE AND RESEARCH CENTRES 51 JOURNALS AND INFORMATION CENTRES 52 REGIONAL PANORAMA OF CZECH MUSIC CULTURE 53 LINKS (SELECTION) 66 EDITORIAL NOTE The Czech Music Guide presents an actual panorama of contemporary Czech music life with a short overview of history. It has been produced for everyone who is interested - from the specialist and scholarly to the active and practical - to understand Czech music culture and its milieu. 12 ABOUT CZECH REPUBLIC CZECH MUSIC GUIDE 13 ABOUT THE CZECH REPUBLIC The Czech Republic is a landlocked country with The cultural sector is administered by the Minis- a territory of 78 865 m2 lying in the centre of try of Culture, and non-profi t organisations play Europe. The country has borders with Poland, an important role. Since 1989 the latter have Germany, Austria and Slovakia, and is currently taken the form of civil associations, non-profi t divided into 14 regions. Since 2004 the CR has companies, endowment funds, and church legal been a member of the EU. -

MY PRAGUE—Written by a Former Participant in the FIU Czech Study Abroad Pgm Who Returned the Next Year to Prague and Wrote About Her Feelings

MY PRAGUE—written by a former participant in the FIU Czech Study Abroad Pgm who returned the next year to Prague and wrote about her feelings A Gothic footbridge made of stone spans the broad Vltava River, linking five ancient towns together into Prague, the hauntingly beautiful capital city of the Czech Republic. West of the bridge is the Old Town; to the east is Mala Strana (the Little Quarter), a collection of crooked cobbled streets between the river and the castle on the hill. Strolling across Charles Bridge at twilight, the "City of One Hundred Spires" looks distinctly unreal, as dreamlike and hallucinatory as any of the art it has inspired. This is Franz Kafka's city, after all. A town where nothing is quite as it appears. A town steeped in legends and alchemy, with a long, bizarre, rather tragic history. Where the past is tangible, crowding the present-day streets with ghosts and stories. The apartment where I am staying is in Mala Strana, tucked between crumbling Baroque buildings, quiet parks and the bubbling Devil's Stream -- named, I am told, for a demon in the water, or else for a washerwoman's temper. I have come because of the Art Nouveau movement which blossomed here one hundred years before. With its roots deeply planted in Czech folklore, Art Nouveau architecture and design has turned Prague into a fantasist's dream: extravagantly adorned with sprites, undines, and the pensive heroes of myth and legend, standing draped over doorways, on turret towers, holding up the red-tile roofs. -

Folk Music, Song and Dance in Bohemia and Moravia We Look Down on Other Sorts of Music

czech music quarterly 3 | 2 0 0 7 Ivan Kusnjer Folk Music Bohuslav Martinů 2 0 7 | 3 Dear readers, CONTENTS This issue of Czech Music Quarterly slightly deviates from the norm. As you “It’s not age that has turned my hair gray, but life…” have probably noticed, in recent years we Interview with the baritone Ivan Kusnjer have been quite strict about maintaining Helena Havlíková the profile of CMQ as a magazine concerned with classical music (please page 2 note that I don’t put quotation marks round the expression). This is not because Folk Music, Song and Dance in Bohemia and Moravia we look down on other sorts of music. Zdeněk Vejvoda We simply believe that despite its rather all-embracing title, it makes better sense page 14 for our magazine to keep its sights on classical music because this is in line with Saved from the Teeth of Time its own traditions and the mission of the folk music on historical sound recordings Czech Music Information Centre which Matěj Kratochvíl publishes CMQ. What makes this issue different? The thematic section is devoted page 24 to folklore. I will spare you contrived connections like “folk music is important Call of Dudy for classical music, because the romantic Matěj Kratochvíl composers found inspiration in it”. Yes, page 27 folk music is of course an inseparable element of the roots of the musical culture Kejdas, Skřipkas, Fanfrnochs of every country (and ultimately this is one reason we pay attention to folk music), but what people used to play on in Bohemia and Moravia the real position of folk music today and its Matěj Kratochvíl future are matters that are often far from page 27 clear and certain. -

Czech Contributions to the Progress of Nebraska

Czech Contributions to the Progress of Nebraska Editor Vladimir Kucera Co-Editor Alfred Novacek Venovano ceskym pionyrum Nebrasky, hrdinnym budovatelum americkeho Zapadu, kteri tak podstatne prispeli politickemu, kulturnimu, nabozenskemu, hosopodarskemu, zemedelskemu a socialnimu pokroku tohoto statu Dedicated to the first Czech pioneers who contributed so much to the political, cultural, religious, economical, agricultural and social progress of this state Published for the Bicentennial of the United States of America 1976 Copyright by Vladimir Kucera Alfred Novacek Illustrated by Dixie Nejedly THE GREAT PRAIRIE By Vladimir Kucera The golden disk of the setting sun slowly descends toward the horizon of this boundless expanse, and changes it into thousands of strange, ever changing pictures which cannot be comprehended by the eye nor described by the pen. The Great Prairie burns in the blood-red luster of sunset, which with full intensity, illuminates this unique theatre of nature. Here the wildness of arid desert blends with the smoother view of full green land mixed with raw, sandy stretches and scattered islands of trees tormented by the hot rays of the summer sun and lashed by the blizzards of severe winters. This country is open to the view. Surrounded by a level or slightly undulated plateau, it is a hopelessly infinite panorama of flatness on which are etched shining paths of streams framed by bushes and trees until finally the sight merges with a far away haze suggestive of the ramparts of mountain ranges. The most unforgettable moment on the prairie is the sunset. The rich variety of colors, thoughts and feelings creates memories of daybreak and nightfall on the prairie which will live forever in the mind. -

The Influence of Folklore on the Modern Czech School of Composition

The Influence of Folklore on the Modern Czech School of Composition BORIS KREMENLIEV The influences which shaped musical growth in European countries such as France, Italy, and Germany, played a part in the development of Czech music as a major cultural achievement. But in addition, the Czech people shared the rich heritage of the Slavs, whose cultural resources had begun forming in primitive societies at the start of the Christian era, or even earlier. When Cyril and Methodius went to Moravia in the 9th century 1 at the invitation of Prince Rostislav, the culture of Byzantium was at a much higher level than that of the Moravians. Thus, the Gospel passages which Cyril translated into Slavic dialects in preparation for his trip 2 can be said to mark the very beginning of Slavic literature. It is not equally clear, however, to what extent Byzantine music influenced that of the Western Slavs in general, and of the Moravians in particular, since the earliest musical records we have go back only to the 12th century.3 After the Great Moravian Empire collapsed in the 10th century, the Roman liturgy emerged victorious in its bitter struggle with the Slavonic liturgy, but the seeds had already been sown so deeply that some Slavonic liturgical tunes lingered long after the 10th and 11th centuries half as sacred tunes, half as folk songs. One of them, for instance, Lord 1 Cyril and Methodius arrived in Moravia in the spring of 863, although, ac- cording to Samuel Hazzard Cross, Rostislav seems to have requested Slavic- speaking missionaries three years earlier (Slavic Civilization Through the Ages, pp. -

Bergsengs Utilize Their Medical Skills on Mission Trip

Glencoe Concert Panthers put out the Fire Series rich in musical heritage Wraspir runs for two TDs in 14-3 victory — Page 2 — Sports Page 1B The McLeod County hronicle $1.00 Glencoe, Minnesota Vol. 120, No. 40 Cwww.glencoenews.com October 4, 2017 Chronicle photo by Tom Carothers Anderson Sanchez, Christensen crowned AJ Anderson Sanchez and Zoe Christensen, in court; front row, from left, crown bearers Kee- photo at right, were crowned as the 2017 Glen- gan Sauter and Gracie Verdon; middle row from coe-Silver Lake Homecoming King and Queen left, Queen candidates Zoe Christensen, Micka- in a ceremony at the high school gymnasium on lyn Frahm, Paige Litzau, McKenna Monahan and Monday, Oct. 2. The pair will preside over GSL’s Ellie Schmidt; back row from left, King candi- Homecoming festivities this week, culminating dates Connor Kantack, Kyle Christensen, Paul with the parade and football game this Friday Lemke, Ethan Wraspir and AJ Anderson evening. Pictured above is the entire royalty Sanchez. Bergsengs utilize their medical skills on mission trip Katie Ballalatak middle of August that had urgent joint injections, dental fillings and Staff Writer needs for a nurse and a doctor so I extractions, eye glasses and medica- etired Glencoe Regional looked into it and signed us up.” tion. Five minor surgeries also were Health Services (GRHS) There were 22 people on the performed during their stay, which Rsurgeon John Bergseng team, including a minister, three were made possible by a suitcase and his wife, Pat Bergseng, a regis- physicians, four physician assis- full of supplies that GRHS donated tered nurse, recently traveled to tants, eight physician assistant stu- for the Bergsengs’ trip.