A Study of English Communication Problems Between

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Thailand COUNTRY STARTER PACK Country Starter Pack 2 Introduction to Thailand Thailand at a Glance

Thailand COUNTRY STARTER PACK Country starter pack 2 Introduction to Thailand Thailand at a glance POPULATION - 2014 GNI PER CAPITA (PPP) - 2014* US$13,950 68.7 INCOME LEVEL million Upper middle *Gross National Income (Purchasing Power Parity) World Bank GDP GROWTH 2014 CAPITAL CITY 1% GDP GROWTH FORECAST (IMF) 3.7% (2015), 3.9% (2016), 4% (2017) Bangkok RELIGION CLIMATE CURRENCY FISCAL YEAR jan-dec Buddhism (90%) 3 distinct seasons THAI BAHT (THB) calendar year SUMMER, RAINY, COOL > TIME DIFFERENCE AUSTRALIAN IMPORTS AUSTRALIAN EXPORTS EXCHANGE RATE TO BANGKOK (ICT) FROM THAILAND (2014) TO THAILAND (2014) (2014 AVERAGE) 3 hours A$10.94 A$5.17 ( THB/AUD) behind (AEST) Billion Billion A$1 = THB 29.3 SURFACE AREA Contents 513,115 1. Introduction to Thailand 4 1.1 Why Thailand? 5 square kmS Opportunities for Australian businesses 1.2 Thailand overview 8 1.3 Thailand and Australia: the bilateral relationship 16 GDP 2014 2. Getting started in Thailand 20 2.1 What you need to consider 22 2.2 Researching Thailand 32 US$387.3 billion 2.3 Possible business structures 34 2.4 Manufacturing in Thailand 37 3. Sales & marketing in Thailand 40 POLITICAL STRUCTURE 3.1 Direct exporting 42 3.2 Franchising 44 Constitutional 3.3 Licensing 46 3.4 Online sales 46 Monarchy 3.5 Marketing 46 3.6 Labelling requirements 47 GENERAL BANKING HOURS 4. Conducting business in Thailand 48 4.1 Thai culture and business etiquette 49 Monday to Friday 4.2 Building relationships with Thais 53 4.3 Negotiations and meetings 54 9:30AM to 3:30PM 4.4 Due diligence and avoiding scams 56 5. -

Die Folgende Liste Zeigt Alle Fluggesellschaften, Die Über Den Flugvergleich Von Verivox Buchbar Sein Können

Die folgende Liste zeigt alle Fluggesellschaften, die über den Flugvergleich von Verivox buchbar sein können. Aufgrund von laufenden Updates einzelner Tarife, technischen Problemen oder eingeschränkten Verfügbarkeiten kann es vorkommen, dass einzelne Airlines oder Tarife nicht berechnet oder angezeigt werden können. 1 Adria Airways 2 Aegean Airlines 3 Aer Arann 4 Aer Lingus 5 Aeroflot 6 Aerolan 7 Aerolíneas Argentinas 8 Aeroméxico 9 Air Algérie 10 Air Astana 11 Air Austral 12 Air Baltic 13 Air Berlin 14 Air Botswana 15 Air Canada 16 Air Caraibes 17 Air China 18 Air Corsica 19 Air Dolomiti 20 Air Europa 21 Air France 22 Air Guinee Express 23 Air India 24 Air Jamaica 25 Air Madagascar 26 Air Malta 27 Air Mauritius 28 Air Moldova 29 Air Namibia 30 Air New Zealand 31 Air One 32 Air Serbia 33 Air Transat 34 Air Asia 35 Alaska Airlines 36 Alitalia 37 All Nippon Airways 38 American Airlines 39 Arkefly 40 Arkia Israel Airlines 41 Asiana Airlines 42 Atlasglobal 43 Austrian Airlines 44 Avianca 45 B&H Airlines 46 Bahamasair 47 Bangkok Airways 48 Belair Airlines 49 Belavia Belarusian Airlines 50 Binter Canarias 51 Blue1 52 British Airways 53 British Midland International 54 Brussels Airlines 55 Bulgaria Air 56 Caribbean Airlines 57 Carpatair 58 Cathay Pacific 59 China Airlines 60 China Eastern 61 China Southern Airlines 62 Cimber Sterling 63 Condor 64 Continental Airlines 65 Corsair International 66 Croatia Airlines 67 Cubana de Aviacion 68 Cyprus Airways 69 Czech Airlines 70 Darwin Airline 71 Delta Airlines 72 Dragonair 73 EasyJet 74 EgyptAir 75 -

Western-Built Jet and Turboprop Airliners

WORLD AIRLINER CENSUS Data compiled from Flightglobal ACAS database flightglobal.com/acas EXPLANATORY NOTES The data in this census covers all commercial jet- and requirements, put into storage, and so on, and when airliners that have been temporarily removed from an turboprop-powered transport aircraft in service or on flying hours for three consecutive months are reported airline’s fleet and returned to the state may not be firm order with the world’s airlines, excluding aircraft as zero. shown as being with the airline for which they operate. that carry fewer than 14 passengers, or the equivalent The exception is where the aircraft is undergoing Russian aircraft tend to spend a long time parked in cargo. maintenance, where it will remain classified as active. before being permanently retired – much longer than The tables are in two sections, both of which have Aircraft awaiting a conversion will be shown as parked. equivalent Western aircraft – so it can be difficult to been compiled by Flightglobal ACAS research officer The region is dictated by operator base and does not establish the exact status of the “available fleet” John Wilding using Flightglobal’s ACAS database. necessarily indicate the area of operation. Options and (parked aircraft that could be returned to operation). Section one records the fleets of the Western-built letters of intent (where a firm contract has not been For more information on airliner types see our two- airliners, and the second section records the fleets of signed) are not included. Orders by, and aircraft with, part World Airliners Directory (Flight International, 27 Russian/CIS-built types. -

Page Control Chart

4/8/10 JO 7340.2A CHG 2 ERRATA SHEET SUBJECT: Order JO 7340.2, Contractions This errata sheet transmits, for clarity, revised pages and omitted pages from Change 2, dated 4/8/10, of the subject order. PAGE CONTROL CHART REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED 3−2−31 through 3−2−87 . various 3−2−31 through 3−2−87 . 4/8/10 Attachment Page Control Chart i 48/27/09/8/10 JO 7340.2AJO 7340.2A CHG 2 Telephony Company Country 3Ltr EQUATORIAL AIR SAO TOME AND PRINCIPE SAO TOME AND PRINCIPE EQL ERAH ERA HELICOPTERS, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ERH ERAM AIR ERAM AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC IRY REPUBLIC OF) ERFOTO ERFOTO PORTUGAL ERF ERICA HELIIBERICA, S.A. SPAIN HRA ERITREAN ERITREAN AIRLINES ERITREA ERT ERTIS SEMEYAVIA KAZAKHSTAN SMK ESEN AIR ESEN AIR KYRGYZSTAN ESD ESPACE ESPACE AVIATION SERVICES DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC EPC OF THE CONGO ESPERANZA AERONAUTICA LA ESPERANZA, S.A. DE C.V. MEXICO ESZ ESRA ELISRA AIRLINES SUDAN RSA ESSO ESSO RESOURCES CANADA LTD. CANADA ERC ESTAIL SN BRUSSELS AIRLINES BELGIUM DAT ESTEBOLIVIA AEROESTE SRL BOLIVIA ROE ESTERLINE CMC ELECTRONICS, INC. (MONTREAL, CANADA) CANADA CMC ESTONIAN ESTONIAN AIR ESTONIA ELL ESTRELLAS ESTRELLAS DEL AIRE, S.A. DE C.V. MEXICO ETA ETHIOPIAN ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES CORPORATION ETHIOPIA ETH ETIHAD ETIHAD AIRWAYS UNITED ARAB EMIRATES ETD ETRAM ETRAM AIR WING ANGOLA ETM EURAVIATION EURAVIATION ITALY EVN EURO EURO CONTINENTAL AIE, S.L. SPAIN ECN CONTINENTAL EURO EXEC EUROPEAN EXECUTIVE LTD UNITED KINGDOM ETV EURO SUN EURO SUN GUL HAVACILIK ISLETMELERI SANAYI VE TURKEY ESN TICARET A.S. -

Order 7340.1Z, Contractions

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION 7340.1Z CHG 3 SUBJ: CONTRACTIONS 1. PURPOSE. This change transmits revised pages to change 3 of Order 7340.1Z, Contractions. 2. DISTRIBUTION. This change is distributed to select offices in Washington and regional headquarters, the William J. Hughes Technical Center, and the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center; all air traffic field offices and field facilities; all airway facilities field offices; all international aviation field offices, airport district offices, and flight standards district offices; and the interested aviation public. 3. EFFECTIVE DATE. February 14, 2008. 4. EXPLANATION OF CHANGES. Cancellations, additions, and modifications are listed in the CAM section of this change. Changes within sections are indicated by a vertical bar. 5. DISPOSITION OF TRANSMITTAL. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. PAGE CONTROL CHART. See the Page Control Chart attachment. Nancy B. Kalinowski Acting Vice President, System Operations Services Air Traffic Organization Date: __________________ Distribution: ZAT-734, ZAT-464 Initiated by: AJR-0 Vice President, System Operations Services 02/14/08 7340.1Z CHG 3 PAGE CONTROL CHART REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM-1-1 and CAM-1-10 10/25/07 CAM-1-1 and CAM-1-2 02/14/08 1-1-1 10/25/07 1-1-1 02/14/08 3-1-15 through 3-1-18 03/15/07 3-1-15 through 3-1-18 02/14/08 3-1-35 03/15/07 3-1-35 03/15/07 3-1-36 03/15/07 3-1-36 02/14/08 3-1-45 03/15/07 3-1-45 02/14/08 3-1-46 10/25/07 3-1-46 10/25/07 3-1-47 -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type AASCO KAA Asia Aero Survey and Consulting Engineers Republic of Korea Civil ABAIR BOI Aboitiz Air Philippines Civil ABAKAN AIR NKP Abakan Air Russian Federation Civil ABAKAN-AVIA ABG Abakan-Avia Russia Civil ABAN ABE Aban Air Iran Civil ABAS MRP Abas Czech Republic Civil ABC AEROLINEAS AIJ ABC Aerolíneas Mexico Civil ABC Aerolineas AIJ 4O Interjet Mexico Civil ABC HUNGARY AHU ABC Air Hungary Hungary Civil ABERDAV BDV Aberdair Aviation Kenya Civil ABEX ABX GB ABX Air United States Civil ABEX ABX GB Airborne Express United States Civil ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ABSOLUTE AKZ AK Navigator LLC Kazakhstan Civil ACADEMY ACD Academy Airlines United States Civil ACCESS CMS Commercial Aviation Canada Civil ACE AIR AER KO Alaska Central Express United States Civil ACE TAXI ATZ Ace Air South Korea Civil ACEF CFM ACEF Portugal Civil ACEFORCE ALF Allied Command Europe (Mobile Force) Belgium Civil ACERO ARO Acero Taxi Mexico Civil ACEY ASQ EV Atlantic Southeast Airlines United States Civil ACEY ASQ EV ExpressJet United States Civil ACID 9(B)Sqn | RAF Panavia Tornado GR4 RAF Marham United Kingdom Military ACK AIR ACK DV Nantucket Airlines United States Civil ACLA QCL QD Air Class Líneas Aéreas Uruguay Civil ACOM ALC Southern Jersey Airways, Inc. -

1) NGIIIA VIVA' NAM CUC HANG KHONG VIVA' NAM� Dec Lip - Tv Do - Flank Phtic � So: 1511 Iod-Ctik Hn Nor, Ngay./11 Thing 8 T'inz 2016

BO GIA0 1 HONG VAN TAI CQNG I-10A XA 1191 C111) NGIIIA VIVA' NAM CUC HANG KHONG VIVA' NAM Dec lip - Tv do - flank phtic so: 1511 ioD-ctiK Hn Nor, ngay./11 thing 8 t'inz 2016 QUYET DINH Ve yiec phe duyet Tai lieu litrovg ciAn khai thac -CT CU L'AY NAPdtia Co so' Thu tuc bay — Thong bao tin ttic hang khOng tai Gang hang khOng QuOc to Nei Bai (1 553 2-0417 CUC TRUbNG CUC HANG KHONG VITT NAM - Can dr Thong ttr so 22/2011/TT-BGTVT ngay 31 thang 3 'lam 2011 ctia BO Giao thong van tai quy dinh ve thn tuc hanh chinh thuOc link ykrc bao • dam hoot Ong bay; - Can c(r Quyet dinh so 121/QD-BGTVT ngay 14 thang 01 'tam 2016 cita Giao thong van tai quy dinh chirc nang, nhiem vu, quyen han va co cau to chac cuo Ckic Hang khong Viet Nam; - Xet de nghi cna Tong cong ty Quail lY bay Viet Nam tai cong van so 2467/Q1_,B-KI, ngay 06 thang 7 nam 2016; Theo de nghi cua Truong phong Quart ly hoat dOng bay Cue Hang khOng Viet Nam, QUYET DINH: Dieu 1. Phe duyet Tai lieu htrOng an khai tilde cna,Co ,s6 ThU tuc bay — Thong bao tin tire hang khong tai Cang hang khOng Quecto NOi Bai (có plrrr • dinh kern theo). Dieu 2. Quyet dinh nay có hieu lkrc ke tir ngay 01 thang 9 n'am 2016 vA bai bo Quyet dinh so: 2226/QD-CHK ngay 30/12/2014 (Ban hanh Tai lieu 1-IDKT ARO/AIS tai Ong HKQT Nei Bai). -

Manuscript Details

Manuscript Details Manuscript number IJIO_2017_311 Title Quantifying the Impact of Low-cost Carriers on International Air Passenger Movements to and from Major Airports in Asia Article type Research Paper Abstract Asia is the world’s most rapidly growing aviation market, and the region now cradles the largest number of low-cost carriers (LCCs). This paper identifies the causal effect of LCC entry on international air passenger flows to and from 30 major airports in Asia using reservation-based international air passenger traffic data for years 2010 and 2015 (N=123,148). In order to bypass the endogeneity arising from self selection of LCCs’ entry decision as well as confounding by unobservables, the paper utilizes multiple identification strategies, namely, difference-in-differences (DID), propensity score matching coupled with DID, DID with inverse-probability weighted regression adjustment, and a fuzzy RDD with the maximum flight range of an aircraft typically used by LCCs as the cutoff. The results consistently show that LCC impact on international air passenger traffic is strictly positive, and is decreasing over distance with slight convexity. Another finding is that the impact of LCC entry net of competition effect holding market concentration constant accounts for the major part of the overall impact, i.e. LCC replacing full-service carriers greatly increases international air passenger movements in Asia. Keywords Air passenger movements, Low-cost carriers, Difference in differences, Propensity scores, Regression discontinuity design, -

Departure Floor (3Rd Floor) 출발 (3층) Arrival Floor (1St Floor) 도착 (1층) Getting to Incheon Int’L Airport (IIA)

Departure Floor (3rd Floor) 출발 (3층) Arrival Floor (1st Floor) 도착 (1층) Getting to Incheon Int’l Airport (IIA) Gangbyeunbungno Jct. Access Roads to Incheon Int’l Airport Expressway Incheon Int’l Airport Expressway Buk-Incheon IC 88 Olympic Expressway Jct. Gimpo Airport IC Seoul No-oh-ji Jct. ① Gangbyeunbungno Jct. Northern and Northeastern Seoul ② 88 Olympic Expressway Jct. Airport Entry Jct. Seoun Jct. Yeouido, Southern Seoul and Eastern Gyeonggi Province Airport Town 1st Gyeongin Expressway Incheon Square IC Seoul International Incheon Beltway ③ Gimpo Airport IC Airport Bucheon Gimpo Airport and Western Seoul Seochang Jct. Sinbul IC ④ No-oh-ji Jct. 2nd Gyeongin Anhyeon Jct. Iljik Jct. Gwacheon Expressway Expressways Linked with Seoul Anyang Pangyo Jct. Beltway (Gyeongbu, Seohae-an and 1st & 2nd Gyeongin Expressways) Yeongdong Jonam Jct. Seoul Beltway ⑤ Buk-Incheon IC Expressway Gyeongbu Northwestern Incheon Expressway Airline Check-in Counters To contact check-in counters of airlines regularly serving Incheon Int’l Airport, call 1577-2600. Passenger Terminal OZ K, L, M Other Airliners(West Wing) G, H, J, K FINAIR (AY) 82-32-743-5698 J Shenzhen Airlines (ZH) 82-2-766-9933 E Mongolian Airlines (OM) 82-2-756-9761 Asiana Airlines (OZ) 1588-8000 Philippine Airlines (PR) 82-2-774-3581 G SkyStar Airways Co.,Ltd (XT) 82-32-743-5460 (J),K E China Eastern Airlines (MU) 82-2-518-0330 Japan Airlines (JL) 82-2-757-1711 G Iran Air (IR) 82-2-319-4555 K F PMT Air (U4) 82-32-744-7473 H Turkish Airlines (TK) 82-2-777-7055 K Chian Xiamen Airlines (MF) 82-2-3455-1666 K Star-Alliance H, J, K S7 Airlines (S7) 82-2-455-1234~5 H Sky-Team D, E Orient Thai Airlines (OX) 82-2-757-6399 K Shanghai Airlines (FM) 82-2-317-8899 Dalavia Far East Airways (H8) 82-32-743-2620 H H Aeroflot-Russian Int. -

British Man Charged Over Stepson's Death

Volume 14 Issue 29 News Desk - Tel: 076-236555 July 21 - 27, 2007 Daily news at www.phuketgazette.net 25 Baht The Gazette is published Three in association with British man charged tourists over stepson’s death drown in IN THIS ISSUE By Supanun Supawong two days NEWS: Russian tourists out- number Chinese; New incin- KATHU: Englishman David By Sangkhae Leelanapaporn erator ‘on hold’. Pages 2 & 3 Murray, 37, has been charged over the death of his eight-year- PHUKET: Three tourists INSIDE STORY: A silent Korean old stepson, Narid “Curry” drowned in two days in danger- invasion brings tourists, and Budtharai, who allegedly died ous surf conditions at Phuket a new culture, to Phuket. after his head hit the floor while beaches July 14 and 15. Pages 4 & 5 he was being beaten by his step- A Russian housewife, a AROUND THE NATION: New law father for being a poor student. Saudi Arabian man and a may ban mobile phones while Pol Lt Col Passakorn Singaporean man all lost their driving. Page 7 Sonthikul of Tung Tong Police lives: the two men at Patong told the Gazette that the incident Beach and the woman at Bang AROUND THE REGION: Murder occurred at Murray’s condo Tao Beach. in Samui sets the stage for a home in Moo Baan Irawadee, in The first victim was mystery. Page 9 the Ketho area of Kathu District, Singaporean Chua Holk Beng, 34, whose body was pulled from PEOPLE: The man behind the at about 9 pm July 12. Nakkerd Hills big Buddha Curry’s mother, Ramida turbulent surf at Patong Beach statue. -

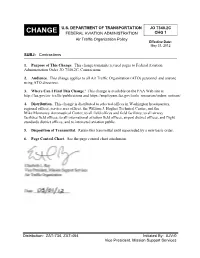

Change 1 to FAA Order 7340.2C Contractions

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2C CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION CHG 1 Air Traffic Organization Policy Effective Date: May 31, 2012 SUBJ: Contractions 1. Purpose of This Change. This change transmits revised pages to Federal Aviation Administration Order JO 7340.2C, Contractions. 2. Audience. This change applies to all Air Traffic Organization (ATO) personnel and anyone using ATO directives. 3. Where Can I Find This Change? This change is available on the FAA Web site at http://faa.gov/air_traffic/publications and https://employees.faa.gov/tools_resources/orders_notices/. 4. Distribution. This change is distributed to selected offices in Washington headquarters, regional offices, service area offices, the William J. Hughes Technical Center, and the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center; to all field offices and field facilities; to all airway facilities field offices; to all international aviation field offices, airport district offices, and flight standards district offices; and to interested aviation public. 5. Disposition of Transmittal. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. Page Control Chart. See the page control chart attachment. Distribution: ZAT-734, ZAT-464 Initiated By: AJV-0 Vice President, Mission Support Services 5/31/12 JO 7340.2C CHG 1 PAGE CONTROL CHART Change 1 REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED TOC−i and TOC−ii .................... 2/9/12 TOC−i and TOC−ii ................... 5/31/12 CAM 1−1 through CAM 1−11............ 2/9/12 CAM 1−1 through CAM 1−4............ 5/31/12 2−1−11.............................. 2/9/12 2−1−11............................. 2/9/12 2−1−12 through 2−1−14................