Everyday Movement Against Capitalism: Prospects for a Prefigurative Strategy Toward Open Utopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libertarian Marxism Mao-Spontex Open Marxism Popular Assembly Sovereign Citizen Movement Spontaneism Sui Iuris

Autonomist Marxist Theory and Practice in the Current Crisis Brian Marks1 University of Arizona School of Geography and Development [email protected] Abstract Autonomist Marxism is a political tendency premised on the autonomy of the proletariat. Working class autonomy is manifested in the self-activity of the working class independent of formal organizations and representations, the multiplicity of forms that struggles take, and the role of class composition in shaping the overall balance of power in capitalist societies, not least in the relationship of class struggles to the character of capitalist crises. Class composition analysis is applied here to narrate the recent history of capitalism leading up to the current crisis, giving particular attention to China and the United States. A global wave of struggles in the mid-2000s was constituitive of the kinds of working class responses to the crisis that unfolded in 2008-10. The circulation of those struggles and resultant trends of recomposition and/or decomposition are argued to be important factors in the balance of political forces across the varied geography of the present crisis. The whirlwind of crises and the autonomist perspective The whirlwind of crises (Marks, 2010) that swept the world in 2008, financial panic upon food crisis upon energy shock upon inflationary spiral, receded temporarily only to surge forward again, leaving us in a turbulent world, full of possibility and peril. Is this the end of Neoliberalism or its retrenchment? A new 1 Published under the Creative Commons licence: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works Autonomist Marxist Theory and Practice in the Current Crisis 468 New Deal or a new Great Depression? The end of American hegemony or the rise of an “imperialism with Chinese characteristics?” Or all of those at once? This paper brings the political tendency known as autonomist Marxism (H. -

The State and Revolution: Theory and Practice Contents

The State and Revolution: Theory and Practice Iain McKay This is almost my chapter in the anthology Bloodstained: One Hundred Years of Leninist Counterrrevolution (Oakland/Edinburgh: AK Press, 2017). Some revisions were made during the editing process which are not included here. In addition, references to the 1913 French edition of Kropotkin’s Modern Science and Anarchy have been replaced with those from the 2018 English-language translation. However, the bulk of the text is the same, as is the message and its call to learn from history rather than repeat it. I would, of course, urge you to buy the book. Contents The State and Revolution: Theory and Practice ......................................................... 2 Theory .................................................................................................................... 2 The Paris Commune ........................................................................................... 4 Opportunism ....................................................................................................... 7 Anarchism ......................................................................................................... 10 Socialism ........................................................................................................... 18 The Party .......................................................................................................... 20 Practice ................................................................................................................ -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS July 16, 1991 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS LET's EASE the SUFFERING of in Iraq

18548 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS July 16, 1991 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS LET'S EASE THE SUFFERING OF in Iraq. As a result, Saddam is free to per Emaciated pets now prowl Baghdad alleys, THE PEOPLE OF IRAQ secute his own people just as he persecuted set loose by owners who can no longer afford the people of Kuwait. to feed them. International aid has thus far HON. WM. S. BROOMREID We may not be able to remove Saddam, but staved off the apocalyptic rates of disease we can certainly ensure that his people, and and malnutrition feared a few months ago, OF MICHIGAN but conditions remain ripe for an epidemic. not he and his cronies, are in a position to IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES On a back street of Saddam City, the Mosan benefit from the country's financial assets and family spent a recent day bailing raw sewage Tuesday, July 16, 1991 its great wealth of natural resources. from the front room of their mud brick Mr. BROOMFIELD. Mr. Speaker, yester In the recent war in the gulf, America's great home. With Iraq's water system crippled by day's Wall Street Journal brought a fresh re scientific minds and military strategists were bomb damage and lack of spare parts, pipes minder of the pain and suffering being en able to wage a war of terrific ferocity but lim often burst, flooding streets with fetid green dured by the people of Iraq. ited scope. Many Iraqi civilians died, but I'd sludge. The Mosans' three-room hovel, home to 13 In the words of the Journal's reporter, Tony like to think that many more survived because America was intent on aiming its precision people, has no furniture and only one appli Horwitz, who is in Saddam City, "Iraq's econ ance: a creaking refrigerator cooling crusts omy is in a free fall, and so are most of its weapons against Saddam and his military and of bread and chunks of fat, the poor Iraqi's people. -

The Marxist Vol

The Marxist Vol. XII, No. 4, October-December 1996 On the occasion of Lenin’s 125th Birth Anniversary Marxism Of The Era Of Imperialism E M S Namboodiripad The theoretical doctrines and revolutionary practices of Vladymir Illyich Lenin (whose 125th birth anniversary was recently observed by the Marxist-Leninists throughout the world), have well been called “Marxism of the Era of imperialism.” For, not only was Lenin a loyal disciple of Marx and Engels applying in practice their theory in his own homeland, but he also further developed the theory and practices of the two founders of Marxism. EARLY THEORETICAL BATTLES Born in Tsarist Russia which was seeped in its feudal environment, he noticed that capitalism was slowly developing in his country. He fought the Narodniks who advocated the doctrine of the irrelevance and no-applicability of Marxism to Russian conditions. His first major theoretical work was the Development of Capitalism in Russia where he proved that, though in feudal environment, capitalism was rapidly developing in Russia. He thus established the truth of Marxist theory of the working class being the major political force in the development of society. Further, an alliance of peasantry under working class leadership will form the core of the revolutionary forces in the conditions of backward feudal Russia. Having thus defeated the Narodniks, he proceeded to demolish the theory of “legal Marxists” according to whom Marxism was to be applies in perfectly legal battles against capitalism. He asserted the truth that the preparation for the social transformation in Russia should be based on the sharpening class struggle culminating in the proletarian revolution. -

Anarcho-Surrealism in Chicago

44 1 ANARCHO-SURREALISM IN CHICAGO SELECTED TEXTS DREAMS OF ARSON & THE ARSON OF DREAMS: 3 SURREALISM IN ‘68 Don LaCross THE PSYCHOPATHOLOGY OF WORK 19 Penelope Rosemont DISOBEDIENCE: THE ANTIDOTE FOR MISERABLISM 22 Penelope Rosemont MUTUAL ACQUIESCENCE OR MUTUAL AID? 26 Ron Sakolsky ILL WILL EDITIONS • ill-will-editions.tumblr.com 2 43 AK Press, 2010, p. 193. [22] Laurance Labadie, “On Competition” in Enemies of Society: An Anthology of Individualist and Egoist Thought (Ardent Press, San Francisco, 2011) p. 249. The underpinnings of Labadie’s point of view, which are similar to those of many other authors featured in this seminal volume, are based on the assumption that communitarian forms of mutual aid do not necessarily lead to individual emancipation. Rather, from this perspective, their actual practice involves the inherent danger of creating an even more insidious form of servitude based upon a herd mentality that crushes individuality in the name of mutuality, even when their practitioners intend or claim to respect individual freedom as an anarchist principle. [23] The Invisible Committee. The Coming Insurrection. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2009. [24] Anonymous. “Taking Communion at the End of History” in Politics is not a Banana: The Journal of Vulgar Discourse. Institute for Experimental Freedom, 2009, p. 70. [25] Anonymous. Desert. St. Kilda: Stac an Armin Press, 2011, p 7. [26] Ibid, p 68. [27] James C. Scott. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009. [28] PM. Bolo Bolo. Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia, 1995, pp 58–60. [29] Richard Day. -

Agrarian Anarchism and Authoritarian Populism: Towards a More (State-)Critical ‘Critical Agrarian Studies’

The Journal of Peasant Studies ISSN: 0306-6150 (Print) 1743-9361 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fjps20 Agrarian anarchism and authoritarian populism: towards a more (state-)critical ‘critical agrarian studies’ Antonio Roman-Alcalá To cite this article: Antonio Roman-Alcalá (2020): Agrarian anarchism and authoritarian populism: towards a more (state-)critical ‘critical agrarian studies’, The Journal of Peasant Studies, DOI: 10.1080/03066150.2020.1755840 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1755840 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 20 May 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 3209 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 4 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fjps20 THE JOURNAL OF PEASANT STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1755840 FORUM ON AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM AND THE RURAL WORLD Agrarian anarchism and authoritarian populism: towards a more (state-)critical ‘critical agrarian studies’* Antonio Roman-Alcalá International Institute of Social Studies, The Hague, Netherlands ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This paper applies an anarchist lens to agrarian politics, seeking to Anarchism; authoritarian expand and enhance inquiry in critical agrarian studies. populism; critical agrarian Anarchism’s relevance to agrarian processes is found in three studies; state theory; social general areas: (1) explicitly anarchist movements, both historical movements; populism; United States of America; and contemporary; (2) theories that emerge from and shape these moral economy movements; and (3) implicit anarchism found in values, ethics, everyday practices, and in forms of social organization – or ‘anarchistic’ elements of human social life. -

Diverging Roots: the Coming Insurrectionâ•Žs Situationist Lineage

Scholarly Horizons: University of Minnesota, Morris Undergraduate Journal Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 4 July 2017 Diverging Roots: The Coming Insurrection’s Situationist Lineage Timothy Fitzgerald University of Minnesota, Morris Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/horizons Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Fitzgerald, Timothy (2017) "Diverging Roots: The Coming Insurrection’s Situationist Lineage," Scholarly Horizons: University of Minnesota, Morris Undergraduate Journal: Vol. 4 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/horizons/vol4/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Horizons: University of Minnesota, Morris Undergraduate Journal by an authorized editor of University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fitzgerald: Diverging Roots Fitzgerald 1 Tim Fitzgerald HUM 3043 Final Paper Diverging Roots: The Coming Insurrection’s Situationist Lineage Over the past 60 years, there has been a resurgence of anarchism in Western Society. The revolutionary spirit has very much returned to the consciousness of popular culture, if it ever left at all. This ‘comeback’ of anarchist ideology has become progressively louder in the past decade, with the rise of cyberterrorist/hacktivist groups such as Anonymous and Lulzsec, the proliferation of political and governmental distrust following the 2008 recession, and the vocal increase in anti-fascist, anarcho-capitalist, post-left anarchism, eco-anarchism, and insurrectionary anarchist groups and activists such as The Invisible Committee. But many of these ideas haven’t been pulled from thin-air, or ancient ideological tomes that have gone out of fashion. -

Stalin Revolutionary in an Era of War 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STALIN REVOLUTIONARY IN AN ERA OF WAR 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kevin McDermott | 9780333711224 | | | | | Stalin Revolutionary in an Era of War 1st edition PDF Book It was under this name that he went to Switzerland in the winter of , where he met with Lenin and collaborated on a theoretical work, Marxism and the National and Colonial Question. They argue that in the article On the Slogan for a United States of Europe the expression "triumph of socialism [ Seller Rating:. Vladimir Lenin died in January and by the end of that year in the second edition of the book Stalin's position started to turn around as he claimed that "the proletariat can and must build the socialist society in one country". Modern History Review. Refresh and try again. Tucker's subject, however, which isn't Mont I have admired Robert Tucker's work for decades now, and I am glad at long last to take up the first of his two volume study of Stalin. Brazil United Kingdom United States. Retrieved August 27, Egan The major difficulty is a lack of agreement about what should constitute Stalinism. Stalin and Lenin were close friends, judging from this photograph. He wrote that the concept of Stalinism was developed after by Western intellectuals so as to be able to keep alive the communist ideal. Retrieved September 20, Palgrave Macmillan UK. Antonio rated it it was amazing Jun 04, Retrieved 7 October During the quarter of a century preceding his death, the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin probably exercised greater political power than any other figure in history. -

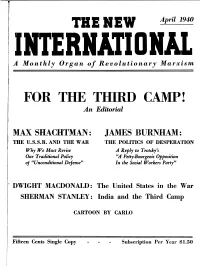

FOR the THIRD CAMP! an Editorial

TBElfEW April 1940 A Monthly Organ of Revolutionary Marxism FOR THE THIRD CAMP! An Editorial MAX SHACHTMAN: JAMES BURNHAM: THE U.S.S.R. AND THE WAR THE POLITICS OF DESPERATION Why We Must Re"ise A Reply to Trotsky's Our Traditional Policy t:~ Petty-Bourgeois Opposition oj t:t:Unconditional Defense" In the Social Workers Party" ( DWIGHT MACDONALD: The United States in the War SHERMAN STANLEY: India and the Third Camp CARTOON BY CARLO Fifteen Cents Single Copy Subscription Per Year $1.50 The Voice of the Third Camp Must Be Heard! Statement by the Editors THE CONVENTION of the Socialist Workers Party, held at as the organized movement of the Fourth International in this the end of several months of internal discussion, has just been con~ country, the Opposition constitutes a clear majority of the total eluded in New York. A majority of the delegates elected to the membership. convention voted for the resolutions on the Russian and organiza Under these conditions, to continue to remain silent inside the tional questions presented by the Majority faction, and which can ranks of the party would be unforgivable in a revolutionist. Under be read in the post-convention issue of the Socialist Appeal. these conditions, to place confidence in the democratic guarantees How deep-going and vigorous was the discussion in the S.W.P. offered by the official party leadership which has given the minority may be judged by the fact that it has brought the party to the no cause to place confidence in it during the course of the internal brink of a split, the danger of which is by no means dispelled. -

Bio-Bibliographical Sketch of Max Shachtman

The Lubitz' TrotskyanaNet Max Shachtman Bio-Bibliographical Sketch Contents: • Basic biographical data • Biographical sketch • Selective bibliography • Notes on archives Basic biographical data Name: Max Shachtman Other names (by-names, pseud. etc.): Cousin John * Marty Dworkin * M.S. * Max Marsh * Max * Michaels * Pedro * S. * Max Schachtman * Sh * Maks Shakhtman * S-n * Tr * Trent * M.N. Trent Date and place of birth: September 10, 1904, Warsaw (Russia [Poland]) Date and place of death: November 4, 1972, Floral Park, NY (USA) Nationality: Russian, American Occupations, careers, etc.: Editor, writer, party leader Time of activity in Trotskyist movement: 1928 - ca. 1948 Biographical sketch Max Shachtman was a renowned writer, editor, polemicist and agitator who, together with James P. Cannon and Martin Abern, in 1928/29 founded the Trotskyist movement in the United States and for some 12 years func tioned as one of its main leaders and chief theoreticians. He was a close collaborator of Leon Trotsky and translated some of his major works. Nicknamed Trotsky's commissar for foreign affairs, he held key positions in the leading bodies of Trotsky's international movement before, in 1940, he split from the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), founded the Workers Party (WP) and in 1948 definitively dissociated from the Fourth International. Shachtman's name was closely webbed with the theory of bureaucratic collectivism and with what was described as Third Campism ('Neither Washington nor Moscow'). His thought had some lasting influence on a consider able number of contemporaneous intellectuals, writers, and socialist youth, both American and abroad. Once a key figure in the history and struggles of the American and international Trotskyist movement, Shachtman, from the late 1940s to his death in 1972, made a remarkable journey from the left margin of American society to the right, thus having been an inspirer of both Anti-Stalinist Marxists and of neo-conservative hard-liners. -

Helen Schiff Papers

Helen Schiff Collection Papers, 1940-1967 .5 linear feet 1 manuscript box Accession #1172 OCLC # The papers of Helen Schiff were placed in the Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs in 1970 by Helen Schiff and were opened for research in May of 1984. In 1940 the Socialist Workers Party split into majority and minority factions over the Hitler-Stalin Pact. The majority faction followed Leon Trotsky's unconditional defense of the Soviet Union's policies; the minority condemned the Hitler-Stalin Pact as an unjustifiable alliance. These differences led the minority faction to leave the Party and to form the Workers Party. In 1957 young members of the Socialist Workers Party joined with left-wing members of the independent Young Socialist League, who were in opposition to their organization's proposed merger with the Socialist Party-Social Democratic Federation, and members of the Labor Youth League, youth section of the Communist Party-USA, to form the Young Socialist Supporters and to publish Young Socialist. In April 1960 the Supporters held a convention and reorganized themselves into the Young Socialist Alliance, youth section of the Socialist Workers Party. In 1965 Young Socialists (Canada) was founded as the youth section of the League for Socialist Action, a fraternal organization of the SWP. The Helen Schiff Collection consists of materials documenting the 1940 split in the Socialist Workers Party and the founding of the Young Socialist Alliance and the Young Socialists (Canada) in the early 1960's. In addition, it contains miscellaneous reports, bulletins, and newsletters of the Socialist Workers Party and the Fourth International. -

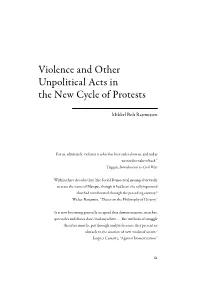

02955 the Aesthetics of Violence OA

Violence and Other Unpolitical Acts in the New Cycle of Protests Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen For us, ultimately, violence is what has been taken fom us, and today we need to take it back.1 Tiqqun, Introduction to Civil War Within three decades they [the Social Democrats] managed virtually to erase the name of Blanqui, though it had been the rallying sound that had reverberated through the preceding century.2 Walter Benjamin, “Teses on the Philosophy of History” It is now becoming generally accepted that demonstrations, marches, spectacles and shows don’t lead anywhere… . Te methods of struggle therefore must be put through analysis because they present an obstacle to the creation of new modes of action.3 Jacques Camatte, “Against Domestication” 61 the aesthetics of violence Afer a 30-year long period of one-sided neoliberal counter- revolution, the last ten years have been characterized by the return of universal disgust against the political status quo. So- cial movements, assemblies, occupations, multitudes, uprisings, riots, and revolts have moved discontinuously across a world united in distrust or outright hatred toward a corrupt political class. Millions of people have taken to the streets, occupying squares, or rioting to protest the austerity and corruption of local political regimes. Most of these protests have been directed at the state, not the economy; it has been the state’s crisis manage- ment that has been the object of resentment and critique. People are disobeying and rejecting the state and its exercise of power. Te threat of a situation of “double power” forces the state to react, and in most places, from Egypt to Hong Kong to France, the state has responded aggressively.